New data highlights pre-incarceration disadvantages

New research illustrates that many formerly incarcerated people never received a fair first chance at economic mobility, never mind a second one.

by Lucius Couloute, March 22, 2018

A striking report from the Brookings Institution, based on new IRS data covering almost 3 million people, shows how our criminal justice system targets people who were already socioeconomically disadvantaged prior to incarceration.

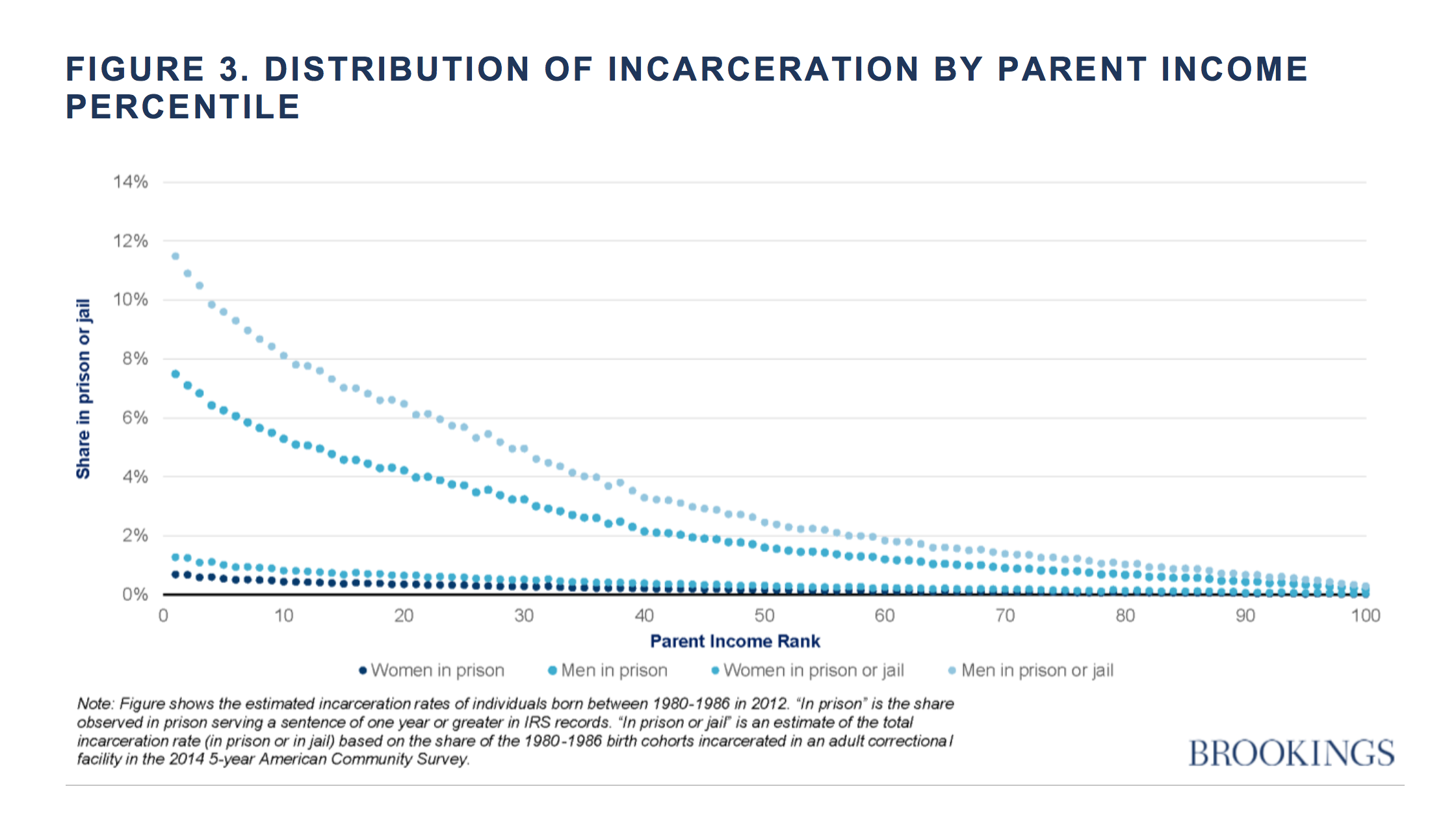

According to the authors, boys born into families at the bottom 10% of the income distribution are 20 times more likely to experience prison in their 30’s than their peers born into the top 10%. Although women make up a smaller share of the overall incarcerated population, the relative likelihood that they experience incarceration is similarly structured by early childhood family income.

Their analysis also shows that those who end up in prison disproportionately come from disadvantaged communities of color with high levels of poverty and unemployment. The data helps us recognize how mass incarceration operates as part of a system, funneling poor people of color from segregated neighborhoods into prisons, and eventually, back into society with little ability to gain an economic foothold.

Only about 53% of formerly incarcerated people report making any money – at all – in the formal labor market three years following their release. Part of the reason is that employers are unlikely to hire people with criminal records, despite growing evidence that blanketed discrimination against this population hurts employers.

But as we’ve argued in the past, the focus on the effects of incarceration sometimes overshadows how pre-incarceration poverty and opportunity structures determine who ends up behind bars in the first place. Report authors Adam Looney and Nicholas Turner, however, show that three years prior to incarceration, only about 49% of working-age people are employed, typically making less than $15,000 a year.

We often talk about reentry as an opportunity for incarcerated people to take advantage of some imagined second chance at life. Yet, this research suggests that the contemporary cultural framing around second chances is misleading at best. Many incarcerated people never received a fair first chance at economic mobility, never mind a second one.