New report, The Company Store, questions fairness and purpose of prison commissaries

In a first-of-its-kind data analysis, we explore the economics of prison commissaries in three states.

May 24, 2018

The ongoing – and growing – exploitation of incarcerated people and their families has been a central theme in our work at the Prison Policy Initiative. In our new report, attorney Stephen Raher explores another overlooked but central part of prison life: the commissary. The fairness of prison commissaries is an essential bread-and-butter issue for incarcerated people, who have only the store’s limited options to choose from when the prison fails to provide them with what they need.

In his report, The Company Store: A Deeper Look at Prison Commissaries, Raher analyzes commissary sales data from three states to address questions like:

- What do people spend the most money on in prison commissaries?

- How “fair” are prices, compared to “free-world” prices and relative to prison wages?

- How does the emerging digital market compare to traditional commissary sales, like food and toiletries?

The three states sampled – Illinois, Massachusetts, and Washington – were the few from which we could easily obtain detailed statewide commissary sales data. Fortunately, this sample includes examples of both state-run and privately operated commissary systems, as well as a range of prison population sizes. While we would warn against generalizing broadly based on this small sample, the report highlights a number of issues that merit further study and serious consideration by policymakers.

The purpose and fairness of prison commissary systems come into question in light of the report’s findings:

- Incarcerated people spent an average of $947 per person annually through commissaries – well over the typical amount they can earn at a prison job. In these three states, an incarcerated worker holding a job supporting the prison, such as food service or custodial work, would usually earn $180 to $660 per year.

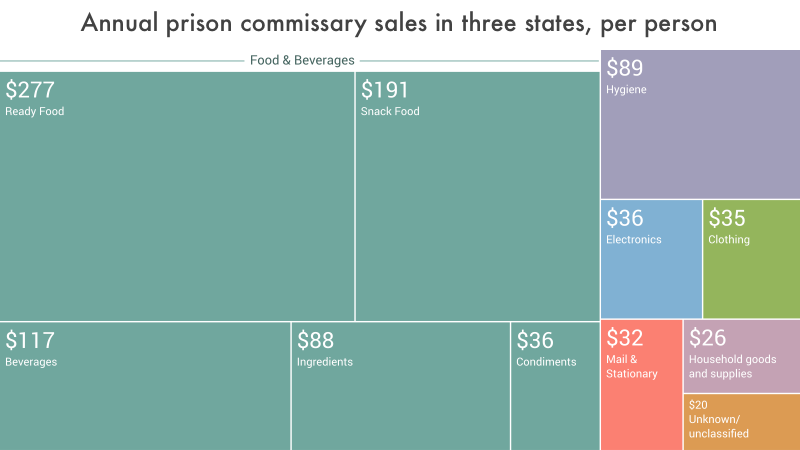

- Incarcerated people buy most items to meet basic needs, like food, hygiene, and over-the-counter medicines, rather than “luxuries.” 75% of the average person’s annual commissary spending in the three sampled states was used to purchase food and beverages, indicating a widespread need to supplement the food provided by the prisons.

The findings also point to the incentives of the prison retail market for private commissary vendors:

- While private vendors generally charge prices comparable to those found in outside prisons, monopoly contracts and the ability to transfer goods straight from the warehouse to the customer mean vendors’ operating costs are often lower than in the “free world.” Yet their prices do not always reflect these advantages.

- The most obvious price-gouging is found in new digital services marketed to prisons, such as email and music streaming. Prison and jail telecommunications providers are aggressively pushing these new products and services, where they can charge prices far higher than similar businesses do outside of the prison setting.

- Even in state-run commissary systems, private companies are poised to profit. In Illinois, the Keefe Group (one of the largest commissary companies) was not contracted to run the commissary, but still made up the dominant share (30%) of the state’s purchases for commissary goods.

Commissaries present yet another opportunity for prisons to shift the costs of incarceration to incarcerated people and their families. Meanwhile, telecommunications contractors with prison contracts are maximizing their revenues by offering more digital services at exorbitant rates. Instead of leveraging incarcerated people to subsidize the prison system by monetizing their every need, the report concludes, states could more effectively cut costs by drastically reducing prison populations.