Felon Disenfranchisement:

Pennsylvania's Sinister Face of Vote Dilution

By Jon E. Yount, March 1998.

[See author's September 2002 postscript for changes in the law since this writing]

" Elections shall be free and equal, and no power, civil or military, shall at any time interfere to prevent the free exercise of the right of suffrage‑." Constitution of Pennsylvania, DECLARATION OF RIGHTS, Article I, §5.

Pennsylvania's manipulated elections and engendered vote‑dilution dilemma for a mushrooming proportion of disenfranchised minority citizens and their communities effectively undermines President Clinton's campaign to "improve race relations". The degree of "intent" driving state officials' complicity in these machinations is open to debate; that the Commonwealth's Election Code denies suffrage to a substantial percentage of protected minorities is etched in stone. The cohesive element and contemporary choice of weapons in this pervasive collusion to estrange African-Americans from the democratic process is the criminal justice system, particularly prisons which serve as repositories for a disproportionate number of non‑whites excised from their communities.

Pennsylvania denies ballots only to those convicted felons sentenced to incarceration rather than probation. For example, one of two defendants convicted of the same felonious offense may be incarcerated while the other is arbitrarily spared imprisonment. The incarcerated citizen is then denied access to the ballot not only during imprisonment but also for five years following release from prison. Conversely, the equally culpable felon who capriciously avoided imprisonment endures no such estrangement from the essence of democracy. Notably, legislative fiat and not provisions of Pennsylvania's constitution is the linchpin of such disenfranchisement and vote dilution so toxic to empowerment of minorities.

To guard against transgressions of the high powers which we have delegated, we declare that everything in this article is excepted out of the general powers of government and shall forever remain inviolate." Constitution of Pennsylvania, Article I, §25

A Not‑So‑Hidden Agenda

In a published interview,[1] Jerome Miller, Executive Director of the National Center On Institutions and Alternatives and former juvenile justice administrator, claims that the "war on crime" has a hidden agenda that centers on the poor and minorities. He predicts that by 2000 the majority of young black men will either be locked up, on probation or on parole.

Projecting those predictions onto the state's tough‑on‑crime policies, the resulting collage is frightening indeed! Prisons have become the juiciest pork in the barrel … an inevitable food fight among rural, "white" locales seeking crime-related job security and economic growth. As a result, the number of state penitentiaries has increased from 6 to 24 ‑ plus one boot camp, most of which have been erected in the state's hinterlands.[2] More are to come on line!

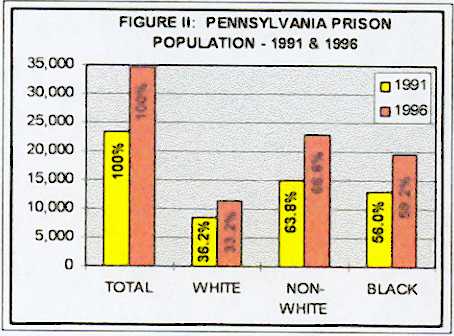

Between 1980 and 1995, the state prison population quadrupled (8,243 to 32,310!)[3] The incarceration rate concurrently increased from 69.9 (1980) to 268.5 (1995) to 286.5 (1996) per 100,000 residents.[4] The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the Commonwealth's prison population as of March 4, 1998, was 35,075. Two‑thirds of those prisoners are nonwhite![5] At any given time, more than 20,000 prisoners of similar racial make‑up are confined in county prisons and jails.[6]

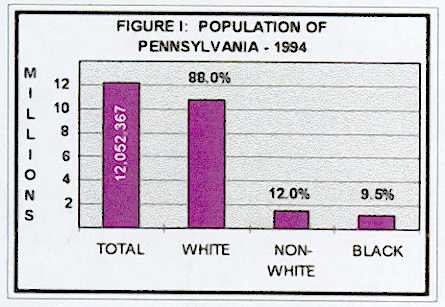

Comparison of 1990‑94 census data and the Commonwealth's prison population reveals disturbing trends as well as the impact of those trends upon minorities and their communities. Figures I[7] and II illustrate the disparity between the state's general population and the racial configuration of incarcerated felons.

That 12% of Pennsylvania's population supplies two‑thirds of its prisoners is primarily attributable to the racial disparity in police contacts[8], drastically reduced parole opportunities[9] and the General Assembly's ill‑advised enactment of dozens of mandatory sentencing laws[10] ‑ especially for repeat offenders,[11] drug offenses[12] and firearms‑related crimes.[13] Moreover, that a mere 10.3% of employees of the DOC are nonwhite[14] when 67% of those in their custody are Black and Hispanic is an enigma spawned by a race‑coded criminal justice system.

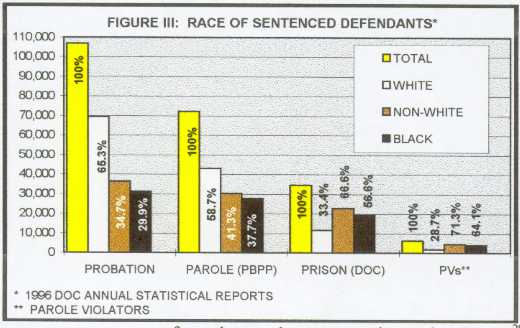

The PCCD observed that a large body of literature indicates that despite criminal behavior of both whites and nonwhites being fairly comparable, police treat apprehended offenders differently based on race and more often decline to arrest whites than non‑whites.[15] This pattern of minority overrepresentation among the state's imprisoned is comprehensively illustrated by Figure III.

The Philadelphia Story

Since minorities are most at risk from mandatory sentences, the home of the Liberty Bell has become the alternate target for those who opt to utilize the criminal‑justice system not only as "rural welfare" but also as a vehicle for diluting minority representation in government. Total arrests during the first third of 1998 are up 15% to 25% across the city.[16] Compared to the 286.5 incarceration rate for the Commonwealth, the rate for Philadelphia climbed from 869.7 to 946.6 per 100,000 between 1995 and 1996![17] Approximately 40.5% of DOC prisoners emanate from "The City of Brotherly Love"[18] ‑ as many as 86% of whom may be nonwhite.[19]

Extrapolation illustrates that of the more than 23,000 nonwhites currently consigned to the DOC, 14,000 have been expelled from the state's most populous urban center.[20] This systemic predation upon minorities is exacerbated by the average length of stay for state prisoners having steadily grown from 35.5 months in 1991 to 44.4 months in 1996.[21] Although only 40% of Philadelphia County residents are black, 66% of its felony defendants are black and 65% of those convicted are sentenced to imprisonment rather than probation.[22] This disproportionate number of nonwhites disenfranchised by imprisonment represents an invidious form of gerrymandering that substantially dilutes, the access of minorities to the ballot as well as to preferred representation in government.

The Corrections‑Industry Complex

The genesis of Pennsylvania's disproportionate incarceration of nonwhite felons is multifaceted. Despite annual statistics published by the U.S. Dept. of Justice[23] documenting a substantially declining crime rate, prison construction is for the Nineties what the "drug war" was to the Eighties … a moral jihad.

A "lock‑'em‑up‑and‑throw‑away‑the‑key" response has emerged to accommodate the burgeoning corrections‑industry complex, especially theme‑stocks‑of‑the‑Nineties crime-control commerce with its profit‑conscious constituency of state and federal law enforcement,[24] architects, vendors, labor unions, developers, financiers, hopeful private‑prison operators and other entrepreneurs who traffic in "grease" for the wheels of justice. Consequently, public office seekers push the agenda of lobbyists/power brokers for the prison industry who stroke political ambitions which, in turn, breed manic activity to enact the toughest prison‑expanding laws. Crime! Prisoners! Prisons! It's a natural! Pick on them! They can't vote!

In addition to the DOC's 1998‑99 Capital Budget of $772 million, its General Budget of $1.1 billion further incites the feeding frenzy of corrections‑related entrepreneurs. Does this pursuit of corporate wealth and economic security for job‑seeking rural communities drive the disenfranchisement of a disproportionate percentage of minorities? Is race, as suggested by Jerome Miller, the hidden agenda of the criminal‑justice system? Regardless, the results of either or both agenda impact disproportionately upon the ability of minorities to utilize the essence of democracy.

The egregious policy of denying ballots to African‑Americans is not a novel concept! Neither is the propensity for a majority to pursue wealth on the backs of minorities. The criminal‑justice flagship of these profitable shipments of human cargo from urban minority enclaves to welfare‑seeking rural white regions is strikingly similar to the eighteenth century slaver flotillas of Black misery ‑ as well as lesser numbers of white indentured servants ‑ upon whose servitude white entrepreneurs sought wealth.

The foregoing statistics are particularly relevant inasmuch as minority challenges to resulting vote dilution require proof that they "have less opportunity than other members of the electorate to participate in the political process and to elect representation of their choice".[25] With no evidence of an abatement in political pontificating regarding a self‑serving crime war, steadily increasing numbers of Pennsylvania's nonwhites can anticipate being exiled to rural lock‑ups. Yet, the Pennsylvania criminal‑justice system's treatment of Blacks and Hispanics is not unusual.[26] What is unique is the circuitous manner by which the Commonwealth disenfranchises this verminized segment of the electorate.

Such abhorrent restructuring of the state's electorate should incite civil rights advocates to challenge this persistent injustice. To comprehend the nexus between incarceration rates and dilution of minority participation in electing preferred representation, as well as to grasp the link between an incommensurate rate of arrest and imprisonment of minorities and the state's qualification of absentee electors, one must look to relevant constitutional and statutory provisions.

Constitutions & Statutes

"No legislative enactment may contravene the requirements of the Pennsylvania or United States Constitution."[27]

Article I of Pennsylvania's Constitution, "Declaration of Rights", mandates not only that "no power, civilian or military, shall at any time interfere to prevent the free exercise of the right of suffrage"[28] but also that "everything in this Article is excepted out of the general powers of government and shall forever remain inviolate"[29] and that "neither the Commonwealth nor any political subdivision thereof shall deny to any person the enjoyment of any civil right, nor discriminate against any person in the exercise of any civil right".[30]

Sections of the state constitution entitled "Qualification of Electors"[31] and "Absentee Voting,[32] are especially germane. The former expressly provides that every citizen of at least eighteen years of age who (1) is a citizen of the United States, (2) has resided in the state for at least ninety days, and (3) has resided in the voting district for at least sixty days:

"shall be entitled to vote at all elections subject, however, to such laws requiring and regulating the registration of electors as the General Assembly enact".

The latter mandates that:

"The legislature shall, by general law, provide a manner in which, and the time and place at which, qualified electors, who may, on the occurrence of any election, be absent from the State or County of their residence, because their duties, occupation or business require them to be elsewhere ... may vote, and for the return and canvass of their votes in the election district in which they respectively reside." (emphasis added)

Consequently, any incarcerated citizen of the United States who is "at least eighteen years of age", and who has resided in Pennsylvania for at least ninety days as well as a voting district for sixty days prior to imprisonment, is by constitutional definition a "qualified elector". Especially relevant is the compulsory language of Article VII, §14, that the General Assembly shall provide a manner by which such a qualified elector may vote when absent from his/her residence because of occupation or duty.

For census purposes, the occupation of an incarcerated offender is cited as "prisoner" or "inmate"; those who escape or attempt to escape are harshly reminded of their duty to comply with the court's sentence of imprisonment, Thus, it appears that incarcerated felons qualify as absentee electors on the basis of "duty" and/or "occupation".

Clearly, the Pennsylvania Constitution does not disenfranchise those convicted of a criminal offense but merely authorizes the General Assembly to require and regulate voter registration in a manner that does not deny the franchise itself. The linchpin of the Commonwealth's disproportionate disenfranchisement of minorities is Pennsylvania's Election Code[33] which, akin to related constitutional provisions, neither expressly disenfranchises incarcerated prisoners nor, for that matter, anyone convicted of a criminal offense.

Instead, the state not only refuses to establish "proper polling places" within prisons for the benefit of incarcerated felons but also utilizes §3146.1 of the Code to abridge their right to vote by manipulating the definition of "Qualified Absentee Elector":

"Provided, however, that the words 'Qualified Absentee Elector' shall in nowise be construed to include persons confined in a penal institution or mental institution."

The Code imposes the ultimate obstacle by denying requisite registration by mail to any person not a "qualified absentee elector."[34] By so regulating voter registration, the franchise itself is denied!

At first blush, the state's highest court appears to agree:[35]

"Elections are free and equal within the meaning of the Constitution when ... the regulations of the right to exercise the franchise does not deny the franchise itself . . . and when no constitutional right of the qualified elector is subverted or denied him."

"The declaration in the bill of rights that elections shall be free and equal, means that the voter shall not be physically restrained in the exercise of his right of franchise by either civil or military authority. .."[36]

Subsequently, however, the state Supreme Court, engaging in a ballet of semantics, condoned the Code's abridgment of the constitutionally guaranteed right of suffrage to incarcerated qualified electors.[37]

The fallacy of the Supreme Court's conclusion that "just as the legislature has the power to define 'qualified electors' in terms of age and residency requirements, so it also has power to except persons 'confined in a penal institution' from the class of 'qualified electors '"[38]is that the state constitution itself expressly defines age and residency requirements.[39] Consequently, the General Assembly cannot seek to amend those qualifications unless it proceeds pursuant to a constitutional amendment. The Court's acknowledgment that legislative denial of suffrage for incarcerated felons equates with changing age and residency criteria appears to require a constitutional amendment in order to exclude incarcerated felons from a classification of qualified electors.

Moreover, unlike §8 of the Declaration of Rights which bars only "unreasonable" infringement upon privacy,[40] the plain language of Article 1, §5, bars any and all infringement upon the right of suffrage. Thus, any claim that the legislature may impose "reasonable" restrictions upon one's right to vote (e,g., because of conviction of a felony) is irreconcilable with this express distinction.

Notably, framers of the state constitution understood how to disqualify on the basis of criminal conviction and would have expressly disenfranchised felons if that had been their intent:

"No person hereafter convicted of embezzlement of public moneys, bribery, perjury or other infamous crimes, shall be eligible to the General Assembly, or capable of holding any office of trust or profit in this commonwealth.[41]

That the authors of the constitution and ratifying "qualified electors" opted to expressly disqualify convicts from holding public office but chose not to deny them suffrage would appear to preclude the General Assembly from doing so. Absent a constitutional amendment, no authority exists for tampering with what constitutes a "qualified elector" so as the deny the franchise.

Similar protection of the right of suffrage is offered by the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States:

Section 1: "The right of the citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude"

Section 2: "The Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation."

However, just as ostensibly race‑neutral devices such a property and poll taxes or literacy tests with "grandfather clauses" and "good character" provisos were historically utilized to disenfranchise Black voters, Pennsylvania is subtly employing its criminal justice system to perpetuate an ugly pattern of pervasive racial discrimination. [42] The statute defining qualified absentee elector so as to exclude incarcerated felons may be neutral on its face but is insidiously discriminatory on the basis of race when coupled with criminal justice practices and procedures.

Attorney General Decrees

The Election Code's exclusion of those confined in penal or mental institutions from "qualified absentee electors" has been reduced by edicts of Pennsylvania's Attorney General. A 1973 opinion of the AG instructed:

"a person who resides at institutions for the mentally ill or mentally retarded in the state cannot lawfully be denied the right to register as a qualified elector in the voting district in which the institution is located".[43]

All incarcerated citizens remained disqualified as absentee electors until a related decision of the U.S. Supreme Court[44] spawned another AG decree[45] that advised

"Exclusion of persons confined in a penal institution from qualified absentee electors shall apply only to inmates convicted for felonies, but convicted misdemeanants and pretrial detainees shall be entitled to register and vote during confinement in penal institutions.

Thus, neither conviction of a felony nor incarceration in a penal institution, standing alone, serves to exclude offenders from the ballot. An analysis of mushrooming felony arrests and exponential increases in the duration of imprisonment for a disproportionate number of nonwhites reveals the systemic nature of minority vote dilution.

Vote Dilution Versus Vote Enhancement

In the context of elections for multimember bodies, equal opportunities may be denied in a number of ways. Vote dilution engendered by a weighted system of incarcerating nonwhites to repress minority representation is exacerbated by the DOC's practice of relocating prisoners from urban minority enclaves to penitentiary sites in predominantly white hinterlands where the expatriated are tallied as "residents" during each decennial census.

Inasmuch as the state judiciary instructs that "our Constitution requires that the overriding objective of reapportionment is equality of population", [46]census criteria and the state's shipments of minority voters from urban districts to rural white districts combine to engender two related scenarios of gerrymander.

First, mass relocation of minorities from urban centers where census data would have documented them as residents to rural locales having few nonwhites substantially reduces a minority's opportunity to select representation of its choice in those urban districts. Second, because an obscure clause in the federal constitution [47] has been construed as shielding states from punishment for disenfranchising citizens who participate in crime, Pennsylvania includes prisoners in census data wherever they are incarcerated when apportioning for state districts, thereby benefiting predominantly white rural voting districts that receive these disaffected minority felons.

The more disenfranchised minority prisoners tallied among the 58,000‑plus residents of each receiving white district, the more voting strength accrues to fewer majority electors in that district. Such dispersion of disenfranchised Black and Hispanic citizens among majority voting districts serves to skew census data so as to dilute the voting strength of minorities while enhancing that of the majority.

Judicial Constraints

Given such damning evidence of Pennsylvania's invidious abridgment of the right to vote on the basis of race, the question becomes one of available redress. Deplorably, the media and political pundits have failed to acknowledge this social malady as anything but a benign blip on a panoramic screen of government intrusion into individual freedoms. It is folly to expect relief from legislators who conveniently utilize annual open seasons on offenders as diversions from their collective inability to solve greater social ills.

Moreover, the prospect of convicts employing their votes to hold politicians accountable for inhumane prison conditions must indeed be frightening to public office seekers! However, prisoners enjoy many protections of the federal constitution that are not fundamentally inconsistent with imprisonment itself or incompatible with the objectives of incarceration. Such retained liberty interests encompass the right to be free from arbitrary governmental action affecting significant personal interests. [48]

Inasmuch as suffrage is the fundamental right that preserves all others, it follows that the right to vote should receive our legal system's utmost protection. Unfortunately, Pennsylvania courts have not been receptive to defending an incarcerated felon's liberty interest in the ballot, a right which the United States Supreme Court has categorically described as "the very essence of democratic society". [49]

Judgments by the state judiciary that disenfranchisement of incarcerated felons is constitutional[50] and that the General Assembly has power to except persons confined in a penal institution from this essence of democracy[51] are not matters of attendant impracticalities or contingencies; they are functions of legal design.

Despite acknowledging that the area of Philadelphia in which the majority of African‑Americans reside is the most depressed in the state and "particularly in need of suffrage free of dilution and manipulation", [52] the Commonwealth's highest court approved this arbitrary discriminatory disenfranchisement, noting that whether election laws and procedures are constitutional is a "matter of degree" to which the "interests that the State claims to be protecting, and the interests of those who are disadvantaged" are impacted.[53]

It is well established that if a challenged statute grants the right to vote to some citizens and denies the franchise to others ‑ especially on the basis of suspect criteria such as wealth and/or race, the test is whether those exclusions are necessary to promote a "compelling state interest".[54] To what compelling state interest could a theoretical concern of the Commonwealth in denying absentee ballots to prisoners possibly rise?

Any state interest in this regard is compromised by the arbitrary denial of the opportunity to vote only to felons sentenced to imprisonment and then automatically reinstating the franchise unconditionally five years after release from incarceration[55] whether that occurs upon having served the maximum term or upon being paroled. It is doubtful, despite such mass exclusion from the ballot, that many people feel safer today than they did ten years ago!

The federal judiciary has not been very helpful in the struggle to achieve suffrage for incarcerated felons despite the massaged rhetoric of no less an authority than the Supreme Court of the United States:

"Undoubtedly, the right of suffrage is a fundamental matter in a free and democratic society. Especially since the right to exercise the franchise in a free and unimpaired manner is preservative of other basic civil and political rights, any alleged infringement of the right of citizens to vote must be carefully and meticulously scrutinized."[56]

Although the American Bar Association has recommended that persons convicted of any offense should not be deprived of the right to vote, the nation's highest court has decreed that state laws disenfranchising felons are distinguished from those other state limitations on the voting franchise which have been held invalid under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[57]

In Owens v. Barnes the Third Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that "a state does not violate equal protection by denyingincarcerated felons the right to vote while permitting those who are not incarcerated to do so since the Commonwealth could rationally decide that one of the losses to which an incarcerated prisoner is subject is that of participation in the democratic process".[58]

However, contrary to Owens' alleged and inexplicable "concession" that the Commonwealth "could constitutionally disenfranchise all convicted felons",[59]those who now challenge the state's infringement upon incarcerated felons' right to vote must claim that Pennsylvania has no recourse other than a constitutional amendment in order to bar any convicted felon from access to the ballot. Notably, Owens did not claim "vote dilution" and, as the Court emphasized, failed to allege "unequal enforcement"[60] which now may be argued as the disproportionate incarceration of minority felons.

What both state and federal courts have failed to consider is the impact of vote dilution that occurs when race‑based gerrymandering is utilized to deport African‑Americans from predominantly minority voting districts to white jurisdictions. Such a claim of minority vote dilution is not constitutionally insubstantial ![61] Inasmuch as the impact of this aspect of the Election Code upon the collective ability of members of minority communities to select representation of choice is a case of first impression in Pennsylvania, substantial room for controversy exists.

The Voting Rights Act

Unfortunately, the Equal Protection Clause requires an often‑unattainable standard of proof. Although the central purpose of "equal protection" is prevention of official misconduct that discriminates on the basis of race, the difficulty confronting incarcerated felons is the paucity of demonstrable evidence that a racially discriminatory intent was the motivating purpose of the Election Code.[62]

To defeat the requirement of proving a subtle discriminatory purpose, Pennsylvania's minority communities and their disenfranchised members must turn to the 1965 Voting Rights Act[63] which was enacted to protect provisions of the Fifteenth Amendment as it relates to voting rights of minorities; i.e., to secure not only the opportunity for all qualified citizens to cast their ballots but to also guarantee that an individual's right to vote will not be diluted.[64]

"(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or standard or practice or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision in a manner which results in a denial or abridgment of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color..

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section is established if . . . it is shown that the political process leading to nomination or elections in the State or political subdivisions are not equally open to participation by members of a class of citizens protected by subsection (a) of this section in that its members have less opportunity than other members of the electorate to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice."

This 1982 amendment to §2 of the Voting Rights Act adopted a "results test" for claims of elector disenfranchisement, affirming that a plaintiff need not demonstrate that the challenged statute or procedure was designed or maintained for a discriminatory purpose:"[65]

The irrefutable result of the Commonwealth's Election Code is the estrangement of a substantial and disproportionate segment of its minority citizens from the "essence of democracy". Applying the §2 results test, the Code violates the Voting Rights Act if, under the "totality of circumstances", denial of voting rights to incarcerated felons results in a protected minority having less opportunity than other members of the electorate to elect preferred representation. [66]

A showing of disproportionate racial impact alone does not establish a per se violation of the Voting Rights Act but merely directs a court's inquiry into the "interaction of the challenged legislation with those historical, social and political factors generally probative of dilution."[67]

"The essence of a Section 2 claim is that a certain electoral law, practice or structure interacts with social and historical conditions to cause an inequity in the opportunities enjoyed by black and white voters to elect their preferred representatives. "[68]

The intrinsic aspect of racial vote dilution can be enhanced by cultural, political, social and economic factors in which the racial minority is relatively disadvantaged and which further operate to diminish political effectiveness.[69]

Congress listed among "typical factors" to be applied when ascertaining if the challenged legislation violates §2:[70]

"the extent to which members of the minority group in the state or political subdivision bear the effects of discrimination in such areas as education, employment and health which hinder their ability to effectively participate in the political process".

It is axiomatic that racial bias in education, employment and health care opportunities have traditionally fomented crime. Another particularly relevant factor addressed in the Senate Report is the extent to which the policy underlying the disenfranchising statute is tenuous. What could be more lacking in sound basis than molding the definition of qualified absentee elector to deny ballots to only felons who are sentenced to imprisonment, two‑thirds of whom are nonwhite?

Factors listed in the Senate Report are neither exclusive nor controlling. To the extent that the enumerated factors are not factually relevant, they may be replaced or substituted by other, more meaningful factors.[71] Disproportionate imprisonment of minorities based upon discriminatory arrest, charging, sentencing and parole procedures appears to qualify as a more meaningful factor.

"Those who argue that these skewed [incarceration] rates merely reflect crime patterns in these areas will have to explain away an extensive body of scholarship showing the pervasiveness (sic) of racial discrimination at every stage of our criminal justice system including arrest, convictions and sentencing."[72]

Recourse

The foregoing compels a coordinated, double‑edged judicial challenge designed to regain suffrage for felons who are imprisoned or have been incarcerated within the past five years and to reverse vote dilution for minority communities.[73] Such a bilateral approach requires the timely filings of state and/or federal lawsuits by one or more affected nonwhite prisoners and one or more community‑based organizations with legal standing; i.e., a community group whose purpose is to vindicate the rights of minorities.[74] The NAACP is but one of many organizations that may ally itself with nonwhite prisoners in a challenge geared to attain access to the ballot for the disenfranchised.

That cooperation of minority communities is imperative in such a legal challenge is revealed in an enlightening decision regarding denial of the ballot to New York prisoners.:[75]

"Political empowerment of those convicted of crime cannot necessarily be assumed to be in the interest of citizens who are members of minority communities. The Equal Protection Clause and the federal Voting Rights Act seek to protect such citizens. The victims of crime are also predominantly members of minority groups."

Subsequent to acknowledging the significance of minority‑community involvement in vote‑dilution claims, the district court condemned the preponderance of imprisoned minorities as a "subject of profound concern", but denied relief for fear that empowering felons to vote might swamp local elections and leave prisoners to "guide the destiny" of municipalities[76]. The Court recognized that such implications do not exist with regard to broader aspects of prisoner voting.[77]

Notably, the domicile of a prisoner is not a factor in Pennsylvania inasmuch as the Election Code explicitly addresses concerns about swamping local elections with prisoners' ballots while concurrently avoiding reducing the weight of the minority vote in the state and in voting for members of the Electoral College: [78]

"For the purpose of registering and voting, no person shall be deemed to have gained a residence by reason of his presence, or lost it by reason of his absence, while .... confined in a public prison."

Similarly, an incarcerated Vermont felon retains the right to vote by absentee ballot at the last voluntary residence, but may not acquire residence at the site of incarceration. [79] Massachusetts authorizes incarcerated persons to vote in statewide elections, [80] a fundamental right guaranteed by that state's constitution. Akin to Pennsylvania's "Declaration of Rights", Massachusetts adopted a constitutional provision that guarantees voting as an "essential and unalienable right". [81]

Conclusion

Plain language of the Constitution of Pennsylvania appears to bar the General Assembly from narrowing constitutional rights:

"State Constitutions ... typically establish governments of general powers, which possess all powers not denied by the state constitution. Our state constitution functions this way and restrains these general powers by a Declaration of Rights . . We agree with the general proposition that those rights enumerated in the Declaration of Rights are deemed inviolate and may not be transgressed by government."[82]

Yet, the interaction of §3146.1 of the Election Code with racial discrimination in Pennsylvania's criminal justice system not only results in denial of the right to vote because of race but also in dilution of the minority vote thereby invoking the protection of §2 of the Voting Rights Act. In addition to the preceding analysis of relevant law and statistical data, joint community and prisoner judicial challenges must assert that challenges to the absence of alternative means to vote in person have been consistently denied thereby imposing an absolute denial of incarcerated felons' right to vote.

Trading ballots for bullets makes sense! However, as in the communist‑bashing McCarthy era, office‑seekers are vying to outdo each other in standing up to the only available enemy: CRIME. A commonly expressed indictment of politicians is that they collectively respond only to money and/or votes. Unfortunately, the growing number of incarcerated Black and Hispanic felons has little of the former and none of the latter!

Inasmuch as Pennsylvania's criminal justice system is designed to entrap disproportionate numbers of nonwhites within state prisons, exclusion of minorities from political clout because of incarceration is a Catch‑22 of epic proportions. Achieving the right to vote for incarcerated felons has as much to do with their families and communities to which they will return upon release as with the prisoners themselves. To stem the flow of vote dilution by attaining access to the ballot for felons, the disenfranchised must join with community‑based, minority‑interest groups in a judicial challenge to this invidious agenda. If successful, state prisons may become whistlestops on the campaign trails of the politically ambitious rather than repositories of citizens denied the essence of democracy!

* * *

The author is a graduate of the Pennsylvania State University and a life‑sentence prisoner currently serving his thirty‑first year of incarceration at the State Correctional Institution at Huntingdon, Huntingdon, Pennsylvania.

As of September 2006, Mr. Yount's address is:

Jon Yount AC8297

175 Progress Drive

Waynesburg PA 15370

POSTSCRIPT TO "FELON DISENFRANCHISEMENT PENNSYLVANIA'S SINISTER FACE OF VOTE DILUTION"

During November 1999, the author petitioned Pennsylvania's Commonwealth Court to declare state statutes that disenfranchised confined felons during incarceration and for five years after release to be violative of the Commonwealth's constitution. The group of petitioners was comprised of six state prisoners (four black, one Latino and one white) and one black resident of a minority district of Philadelphia.

The petition challenged, in part, such disenfranchisement's enhancement of the power of predominately white, rural, prison‑district voters and their legislative representation while those fundamental aspects of democracy were concomitantly diluted for urban minority voters and districts. Samuel C. Stretton, a well‑known West Chester civil‑rights attorney, then entered his appearance to provide probono representation in this action.

On September 18, 2000, the Commonwealth Court struck down sections of the Pennsylvania Voter Registration Act that denied voter registration to felons for five years after release from confinement. (Lorenzo L. Mixon, et. al. v. Com. Of PA, No 384 M.D. 1999) However, the Court refused to opine that election laws denying absentee ballots to confined felons is unconstitutional. Notably, the state legislature, reacting to the Florida fiasco represented as a 2000 presidential ballot count, soon thereafter amended election laws to reinstate the precise language struck down by the court's September, 2000 order. Attorney Stretton petitioned the court to expand its permanent injunction against denial of registration to released felons to include provisions of the amended code. The court granted his petition.

The result of this litigation is that confined felons remain disenfranchised. Misdemeanants ‑ confined or otherwise ‑ and felons sentenced to probation or released from confinement are eligible to vote in Pennsylvania. Political and economic power of rural prison districts continues to be enhanced while that of urban, predominately minority districts is diminished.

[1] "Race ‑ The Hidden Agenda of the Justice System", Just News, February, 1995, published by the National Inter‑Religious Task Force On Criminal Justice and reproduced from "The Humanist", January/February, 1994.

[2] "1996 Annual Statistical Report", Department of Corrections ["DOC"], p. 4 (does not include recently opened SCI Chester); see The Indiana Gazette, "Overcrowding Drives State Prison Costs Out Of Sight", February 16, 1998; p. 13

[3] "Fastfacts '95, Brief" DOC Inmate population profile; supra. note 2, pp. 23 & 28; ; Infra. note 4 at p. 49.

[4] "Trends and Issues in Pennsylvania's Criminal Justice System", Pa. Commission on Crime and Delinquency ["PCCD"], pp. 15, 33 (1995).

[5] Supra. note 2 at p. 23.

[6] Pa. Commission on Corrections Planning ‑ "Final Report 1993", pp. 14‑15; 1990 jail population was 17,915, projected to be 26,600 by 2000.

[7] Statistical Abstract of the U.S. ‑ 1994, 114 Edition, The Reference Press, pp. 35‑36.

[8] Supra. at note 4, p. 35: During the past decade, six times more minority citizens were arrested (523.8 whites per 100,000 whites for every 3012.6 nonwhites per 100,000 nonwhites).

[9] Supra., note 2 at page 41.

[10] Nonwhites account for 39% of all adult sentences imposed but 74% of all mandatory sentences and 80% for all drug‑offense mandatory sentences; Justice Analysis, "Mandatory Sentences in Pennsylvania; PCCD Bureau of Statistics and Policy Research", Vol. 9, No. 1, page 5, Feb. 1995.

[11] Supra. note 4 at p. 36: Of all juvenile cases processed during 1993, 46% involved white defendants; yet, almost 75% of young offenders sentenced to juvenile-delinquency institutions were Black or Hispanic ... all fodder for the adult prison system.

[12] Id. at pp. 35, 41: Approximately 52% of drug‑offense arrests and 60% of state inmates sentenced for drug offenses are nonwhite; supra. note 2 at p.27: While white males imprisoned for drug offenses increased 477% from 1980 to 1990, black males incarcerated for such offenses mushroomed 1,613% (the rate for black women concurrently increased by 1,750%)!

[13] Id. "Minorities are disproportionately arrested for offenses which have relatively high conviction rates ... nonwhites are disproportionately affected by mandatory-minimum incarceration sentences."

[14] "Fastfacts '94", DOC, p. S-5; supra. note 2 at p. 51: DOC personnel increased from 9.427 to 11,768 between 1994 and 1996.

[15] Supra. note 4 at pp. 37, 42.

[16] "A Sharp Increase In Phila. Arrests", The Philadelphia Inquirer, B1, 4‑26‑98.

[17] Supra. note 2 at p. 23.

[18] Id. at p. 26.

[19] "Sentencing in Pennsylvania 1996"; Pa. Commission on Sentencing: 1996 Annual Report, p. 18, Philadelphia County sentenced 6,005 defendants during 1996, 86% of whom were non‑white.

[20] 1,525,338 (1994); The World Almanac ‑ 1996, Funk & Wagnells, p.388

[21] Supra note 2 at pp. 41, 49: While incarceration sentences increased 270% from 1980 through 1992, the percentage of state prisoners who were granted parole upon completion of their minimum sentence dropped from 81% in 1980 to 71.2% in 1992 to 38.8% in 1996. The number of prisoners who were required to serve their entire sentence ("max out") increased from 1,072 in 1995 to 1,814 in 1996.

[22] Supra, note 19 at pp. 18 , 20; Although only 12% of 71,021 defendants statewide were sentenced to imprisonment for an average minimum term of 28.4 months in 1996, 26% from Philadelphia County were exiled to state prisons for an average minimum of 39.3 months.

[23] "Trends in Crime Rate, 1973‑90", U.S. Dept. of Justice, Bureau of Statistics, 1992 Annual Report: "In several major crime categories, victimization rates have been declining fairly consistently since the survey began in 1973. Since 1981, the peak year for victimizations, crime levels have dropped 17% overall, 8.7% for violent crimes.

[24] Jan Elvin, "'Corrections‑Industrial‑Complex' Expands in the U.S.", The National Prison Project Journal (ACLU), 1995 Status Report, p.1; supra. note 2, p, 8: 50 "multi‑jurisdictional task forces" have been created in Pennsylvania since 1987.

[25] Ortiz v. City of Philadelphia, 28 F.3d 306, 324‑25 (3rd Cir. 1994). Allen v. State Board of Elections, 89 S.Ct, 817, 834 (1969).

[26] Andrew Shapiro, "Giving Cons and Ex‑Cons the Vote", PRISON LEGAL NEWS, May 1994, p. 2 (reprinted from the YALE LAW JOURNAL).

[27] Shankey v. Staisey, 436 Pa. 65, 68‑9 (1970)

[28] Section 5: "ELECTIONS"; there have been four Pa. "Constitutional Conventions": 1790, 1838, 1874, 1968

[29] Section 25: "RESERVATION OF POWERS IN PEOPLE"

[30] Section 26: "NO DISCRIMINATION BY COMMONWEALTH AND ITS POLITICAL SUBDIVISIONS"

[31] Article VII Section 1

[32] Article VII Section 14

[33] Act of June 3, 1937, P.L. 1333 as amended 25 P.S. §2600‑3591

[34] 25 P.S. §951‑18.1 provides for registration by mail for military personnel and overseas government employees; §951‑18.2 provides for registration by mail for "ill or disabled".

[35] Shankey v. Staisey, 426 Pa. 65, 69 (1969), quoting Winston v. Moore, 244 Pa. 447, 457(1914), citing DeWitt v. Bartley, 146 Pa. 529.

[36] Winston v. Moore, supra., citing Commonwealth v. Reeder, 171 Pa. 505.

[37] Ray v. Commonwealth, 442 Pa. 606, 609 (1971)

[38] Id.

[39] Article VII §1: "ELECTIONS"

[40] Article 1. §8, regarding search & seizure; see United Telephone Co. of Pa. v. Public Utili1y Comm., 676 A.2d 1244, 1252 (Pa. Cmwlth.Ct. 1996).

[41] Article 11, Section 7: "The Legislature, Ineligibility By Criminal Conviction".

[42] See Vinovich v. Quilter, 113 S.Ct. 1149 (1993); Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2816, 2822‑23 (1993)

[43] 1973 Opinion of Attorney General No. 48

[44] Goosby v. Osser, 93 S.Ct. 854 (1973)

[45] 1974 Opinion of Attorney General No. 47

[46] In re 1991 Pennsvlvania Legislative Reappprtionment, 530 Pa. 356 (1992); there are approximately 58,000 residents in each of 203 representative districts. See Article 11, §16 of the Pennsylvania Constitution.

[47] Amendment XIV, §2: "Representatives shall be apportioned among the several states according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each state. But when the right to vote in any election . . . is in any way abridged except for participation in rebellion or other crime, the basis of representation shall be reduced on the proportion which the number of such citizens shall bear to the whole number of citizens..."

[48] Wolff v. McDonnell, 94 S.Ct. 2963, 2974 (1974)

[49] Shaw v. Reno, 113 S. Ct. at 2822

[50] Martin v. Haggerty, 548 A.2d 371 (Pa.Cmwlth. 1988)

[51] Supra. note 37

[52] In re Jones, 505 Pa. 50, 69 (1984)

[53] In re Street, 499 Pa. 26, 31 (1982)

[54] Dunn v. Blumstein, 92 S.Ct. 995, 1003 (1972)

[55] Act of 1995, June 30, P.L, 170, No.25, §501

[56] Reynolds v. Sims, 84 S.Ct. 1362, 1381 (1964)

[57] Richardson v. Ramirez, 94 S.Ct. 2655, 2671 (1974)

[58] Owens v. Barnes, 711 F.2d 25, 28 (1983)

[59] Id. at p. 26

[60] Id. at p. 27

[61] Supra, note 44 : "A claim is insubstantial only if 'its unsoundness so clearly results from the previous decisions of this court as to foreclose the subject and leave no room for the inference that the question sought to be raised can be the subject of controversy"'. (93 S.Ct. at 859)

[62] Washington v. Davis, 96 S.Ct. 2040, 2047 (1976)

[63] 42 U.S.C. §1971 et seq.; see South Carolina v. Katzenbach , 86 S.Ct, 803, 811‑12 (1966) (The enactment of the Voting Rights Act "reflect[ed] Congress' firm intention to rid the country of racial discrimination in voting".)

[64] White v. Regester, 93 S.Ct. 2332 (1973)

[65] Baker v. Cuomo, 58 F.3d 814, 823 (2nd Cir. 1994): "Section 2 protects citizens in two ways. First, it prohibits the use of certain factually neutral voting qualifications that deny the vote to citizens who are disproportionately members of minority groups . . . Second, §2 protects minority groups against schemes, such as certain at‑large voting systems, that dilute minority voting strength."

[66] Thornburgh v. Gingles, 106 S.Ct. 2752, 2764 (1986); supra. note 46.

[67] Wesley v. Collins, 791 F.2d 1255, 1260 (6th Cir. 1986)

[68] Supra. note 65

[69] Wesley v. Collins, 791 F.2d at p. 1259

[70] Senate Judiciary Report No. 205, 97 Congress, 2nd Session 27

[71] Major v. Treen, 574 F.Supp. 325,350 (E.D.La. 1985)

[72] Supra. at note 26

[73] Allen v. State Board of Elections, 89 S.Ct. at 832‑33 ("voting includes all actions necessary to make a vote effective ... the right to vote can be affected by dilution of voting power as well as by an absolute prohibition ").

[74] NAACP v. State of Alabama, 78 S. Ct. 1163 (1958)

[75] Baker v. Cuomo, 842 F.Supp. 718, 720 (S.D.N.Y. 1993) although the district court denied relief, a Second Circuit panel determined on appeal that a "black or hispanic voter from one of these assembly districts might well have standing to assert a cause of action for vote dilution" [Baker v. Cuomo, 58 F.3d at 8241. The panel reaffirmed its opinion via a published denial of a Petition for Rehearing [Id]. The panel, in turn, was reversed by an equally‑divided Court enbanc [Baker v. Pataki] 85 F.3d 919 (1996)], the case being remanded to allow repleading of plaintiffs' claims under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments to the U. S. Constitution.

[76] Baker v. Cuomo, supra.

[77] Id.

[78] Election Code, 25 P.S. §2813: "RESIDENCE OF ELECTORS".

[79] 28 Vi, Stat. Ann. §807

[80] Dane v. Bd. Of Registrars of Voters, 374 Mass. 152.. 372 N.E.2d. 1358 (1978); also see LIFE‑LINES LifeLong C.U.R.E.. Vol. 5, Issue 1, Winter ‑1995, p.7: "Nearly 1000 of the 1300‑plus prisoners of the [Massachusetts] Norfolk Prison registered to vote in the November, 1994, elections. "

[81] Constitution of Massachusetts, Pt. 1, Art. 1.; Attorney General v. Suffolk Count Apportionment Commission, 22 Mass. 598, 601, 113 N.E. 581 (1916) ("the right to vote is a fundamental personal and political right, The equal right of all qualified to elect officers is one of the securities of the Declaration of Rights, Art. 1‑9"

[82] Gondelman v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 520 Pa. 451, 467 (1989)

Scanned from the original by the Prison Policy Initiative. Please report scanning errors to .