Returning from prison and jail is hard during normal times — it’s even more difficult during COVID-19

We review the evidence and call for state and local governments to provide more support for success upon release from prison or jail.

by Wanda Bertram, September 2, 2020

The very same obstacles that make it hard for people released from prison to succeed — homelessness, a lack of transportation, barriers to healthcare, and more — also make it harder to stay safe from the coronavirus. At this moment, where it is well established that depopulating prisons and jails is critical for health and safety on both sides of the walls, it is critical that policymakers focus on the overlooked hardships faced by formerly incarcerated people. We review our research on the struggles of formerly incarcerated people on housing, income and employment, health care, communication, paying burdensome “supervision” fees and more and explain how these challenges are even greater during the pandemic.

Housing

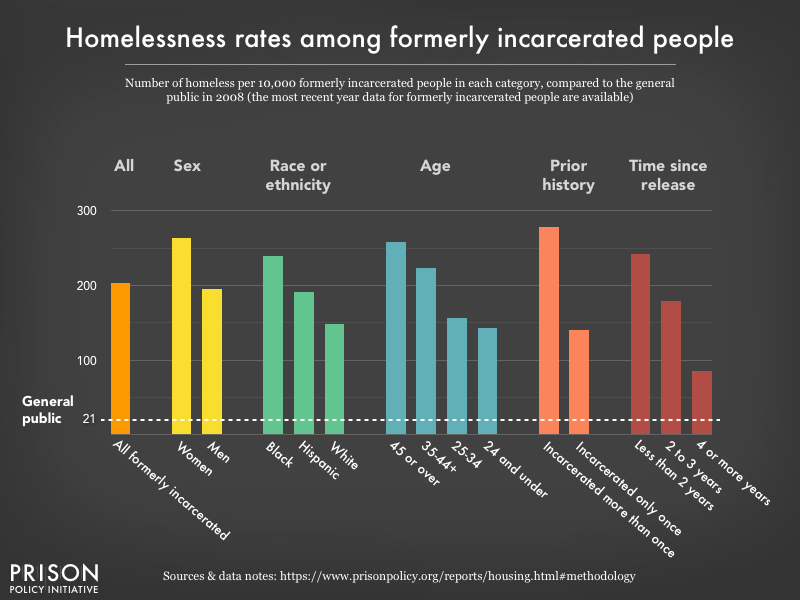

Living without a stable home is even more dangerous than usual during a pandemic, when social distancing and hygiene are especially important. What’s more, people who are homeless risk being re-arrested for “quality of life” offenses such as sleeping in parks. Maintaining housing can even be a parole requirement, the violation of which can land someone back in prison.

Shelters and reentry organizations provide a stopgap to the problem of housing after prison. But even during “normal” times, these organizations are direly under-resourced, as we found in a 2019 investigation of reentry service providers for women. And during a pandemic, many of these organizations are bursting at the seams or have shut down entirely due to their funding being suspended. A housing official in Denver, for example, said that the pandemic, combined with mass releases, had turned the local shelter system “on its head.”

Income and employment

The ongoing recession is likely hitting formerly incarcerated people — and their families — especially hard. As we’ve previously reported, people leaving prison are not only poor (with average pre-incarceration incomes under $20,000), but have seen their existing wealth diminished by incarceration, and must overcome the stigma of a criminal record in order to find work. The effects are worst among Black formerly incarcerated people; Black women who have been to prison, for example, have a 43% unemployment rate.

| Incarcerated people (prior to incarceration) |

Non-incarcerated people | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| All | $19,650 | $13,890 | $41,250 | $23,745 | |

| Black | $17,625 | $12,735 | $31,245 | $24,255 | |

| Hispanic | $19,740 | $11,820 | $30,000 | $15,000 | |

| White | $21,975 | $15,480 | $47,505 | $26,130 | |

Even for people leaving prison who manage to find a job, certain senseless “collateral consequences” of incarceration can make holding down a job difficult. Millions of people, for instance, are barred from getting driver’s licenses (and therefore driving to work) because they haven’t paid a fee or fine, or because they committed an offense that had nothing to do with unsafe driving.

We’ve previously recommended that the government provide a temporary basic income to people leaving prison, but no state has stepped up to do so. And ironically, it’s likely that most people released from prison in the past few months did not receive stimulus checks, as the IRS clawed back checks sent to incarcerated people. If future economic stimulus efforts also exclude people behind bars, those leaving prison during the pandemic will have less of a financial “cushion” to lean on during reentry.

Healthcare

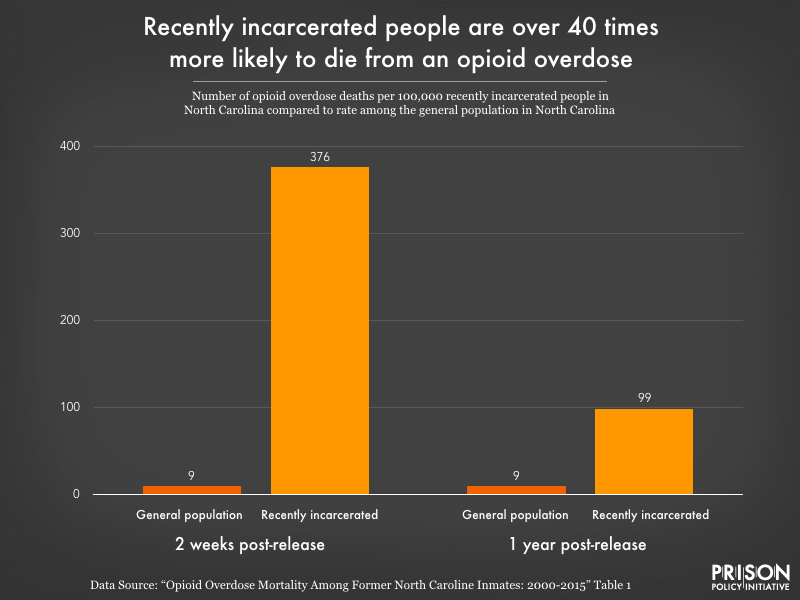

Moreover, people leaving prison are disproportionately likely to suffer from mental health and substance use problems, which require medical attention and therefore health insurance. The consequences of not getting care can be dire: People just released from prison are 40 times more likely to die from an opioid overdose. The stress of the pandemic, which has fallen hard on people with substance dependencies and mental illnesses, can only be making this problem worse.

Unless states immediately act to make sure people leaving prison are Medicaid-insured — such as setting up pre-release enrollment, as a recent article in Health Affairs recommended — people released from prison will be in serious danger.

Phones and communication

Imagine having to communicate with your parole officer, or a reentry service provider, without a phone. Or trying to contact loved ones who might connect you with housing or employment. People leaving prison who can’t afford cellphones have always struggled with this problem, but it’s especially difficult during a pandemic. For instance, while suspending in-person parole check-ins is good public health policy, it leaves people without access to a phone in a bind.

State governments know that phones are essential for successful reentry. Still, news reports from states like Hawaii and Texas reveal that states are leaving people who can’t afford phones to fend for themselves, at the mercy of nonprofits and family members. Those who aren’t lucky enough to have a charity or friend to help them will find it difficult to navigate life after prison, and may even face disciplinary action if they cannot communicate with their probation or parole officer.

Supervision fees

Long before the pandemic, most states decided to require people on parole and probation to shoulder the costs of their own supervision by charging them monthly fees. As we’ve previously shown in our research on the incomes of people on probation, these fees are levied on the people who can least afford them; during a recession, the burden of these costs can be disastrous.

A monthly fee may be just one of several fees that someone on supervision has to pay regularly. As part of the conditions of their supervision, an individual might also have to pay court costs, restitution, electronic monitoring costs, or various one-time charges.

Unfortunately, most state and local governments have an incentive to continue charging these fees even during a pandemic and recession, because the revenue goes to courts, probation and parole offices, and other government agencies. Nevertheless, a handful of counties and states, such as Multnomah County, Oregon, have, since the coronavirus hit, suspended fee collection.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the obstacles that formerly incarcerated people face right now go far beyond the examples listed here: Poverty, combined with the logistical challenges of living in a pandemic, produces countless daily hardships. For instance, NPR recently reported that in many places, the offices that issue driver’s licenses and other forms of ID have been closed, impacting people recently released who need these critical documents.

The good news is that some states have taken some action to ease the pain of reentry. For example, California and Connecticut have made funds available to provide hotel rooms for people released from prisons and jails with nowhere to go. But for the most part, people leaving prison are being ignored, at a time when proper support for reentry is needed now more than ever. Shortchanging reentry is bad criminal justice policy and bad for public health.

My son recently was incarcerated in Levy County, Florida and he’s not showing up in there anymore and I don’t know where he is. I’m worried sick. They kept him for 5 months for DUS. What should I do? Any advice would help. Thank you.

Hi June- I’m so sorry to hear it. I’d try getting in touch with a group based in FL that might be able to help, such as Florida Legal Services: