Can you help us sustain this work?

Thank you,

Peter Wagner, Executive Director Donate

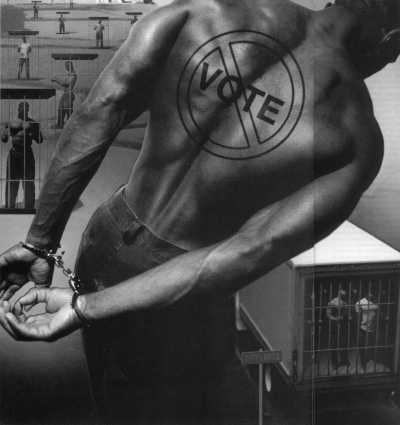

Crime & Punishment

How the U.S prison system makes minority communities pay

By Zachary R. Dowdy

Photo illustrations by John Labbe

The New Crisis Magazine, July/August 2002, pp. 32-37.

When the conservative majority of the U.S. Supreme Court voted to prohibit a recount of Florida ballots cast in the last presidential election, the august body of appointees helped usher George W. Bush into the presidency.

The high court's ruling put to an abrupt end the fierce dispute over whether Bush or his challenger, former Vice President Al Gore, had received a majority of the popular vote in Florida and the right to claim the state's 25 electoral votes. Before the court stepped in, one of the closest presidential elections in U.S. history hinged on a meticulous counting of confusing and arcane ballot cards. While Gore received more than 500,000 popular votes nationally, Bush -- by winning Florida -- because of the halted recount won the majority of electoral votes and thus the presidency.

While all eyes were on Florida, and pundits commented on the complex political machinations they say work to ensure freedom in a democracy, few noted that the election, which was decided by an estimated few hundred votes, could have swung the other way if 400,000 former prisoners in Florida had been allowed to vote. As one of 13 states that permanently deny the right to vote to convicted felons (in four of the states certain conditions related to type of crime and when it was committed apply), Florida harbors an expanding pool of disenfranchised residents who are most often poor, minority and Democrat.

The Florida controversy touches on one of the key areas where the effects of rising incarceration spill over into critical arenas of political and economic power denial of the vote to convicted felons. The others are transfer of funds from minority and poor communities and dilution of minority voting strength.

"Each one of these things chips away at the electoral power, and hence the political power of African Americans," says David Bositis, a researcher at the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, a Black think tank in Washington, D.C.

"And when you put them all together, they represent a major diminishment of Black political power."

Home Away From Home

The 2000 Census estimated that nearly 2 million people are housed in prisons and jails. The political ramifications of these high incarceration numbers include disfranchisement of felons taking away their voting rights either temporarily or permanently loss of federal funding for anti-poverty programs and distortion of electoral power because of the counting of inmates as residents of the communities where they are imprisoned.

But the dramatic increase in imprisoned people over the past 20 years, a phenomenon some criminologists say was fueled by a tough-on-crime tide that began sweeping the nation during the Reagan years and continued under the Clinton administration, has yielded what some analysts term unintended consequences in political representation and the amount of dollars flowing into the nation's cities.

At the start of Reagan's administration in 1980, there were approximately 501,886 prisoners in the nation's prisons and jails, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. In June 2001, there were 1,800,300, a nearly four-fold increase, according to the agency's data. Of this number, 803,400 were Black males and 69,500 were Black females.

One of the effects of this boom has been the shifting of federal funds from the minority and poor communities that export prisoners to poor white towns, which started "hosting" prisons in the 1990s as a means of escaping from economic despair. In fact, new studies are showing that in a society that ratcheted up its criminal penalties to control crime and place offenders out of sight and out of mind, the prison industry has begun to affect the political landscape.

In 1984 there were just about 694 state prison facilities in the country. Now there are about 1,073. "We're seeing a convergence of voting rights and political rights," says Brenda Wright, managing attorney for the National Voting Rights Institute in Boston. "People are understanding that incarceration rates in this country are having a big impact on those issues as well."

There are no statistics on the number of groups using the courts to challenge current redistricting plans based on the 2000 census. But Wright's institute is among many questioning the plans. It is suing the state of Massachusetts on behalf of the minority residents of the city of Chelsea over proposed redistricting plans that it considers racially discriminatory. The institute alleges Chelsea's redrawn House district unlawfully dilutes Latino voting power.

Wright says the construction of prisons and the harsher laws that help send more offenders to fill them have combined to siphon political power from the poor minority communities that may need it most.

"Importing Constituents: Prisoners and Political Clout in New York," a recent study by Peter Wagner, assistant director of the Prison Policy Initiative in Springfield, Mass., concludes that the incarceration boom has all but corrupted that state's redistricting process in ways that benefit the upstate rural and white communities and cheat urban and minority areas of New York City.

A study of Florida, which has a similar penal system architecture with prisons in mostly white towns and prisoners coming from its urban centers, reached a similar conclusion.

Redistricting is the revision of political district boundaries across the nation to reflect population shifts documented by the federal Census, conducted every 10 years. In fact, the Census was established by the federal government in 1790 for the express purpose of reapportionment and redistricting. In theory, state legislators are supposed to redraw the lines to create districts that evenly divide the population to ensure the constitutional right of one person, one vote, the constitutional maxim that each person's vote must be equal to each other person's vote. In practice, this is not always the result.

Wagner says the fact that New York's 71,466 prisoners are counted as residents of the prisons where they are housed and not where they lived before incarceration increases the power of voters upstate, where 91 percent of the state's prisoners are sited in 70 prisons.

"This affects the purity of the process," says Wagner. "The whole idea of representing people is seriously tainted" because New York's prison construction boom has occurred almost solely upstate.

The Florida controversy touches on one of the key areas where the effects of rising incarceration spill over into critical arenas of political and economic power -- denial of the vote to convicted felons. The others are transfer of funds from minority communities and dilution of minority voting strength.

Of the 41 prisons New York has built since 1982,40 have been constructed in upstate towns. As in Florida, none of New York's prisoners are allowed to vote, yet they are counted in the Census as residents of the mostly white communities where they serve prison terms. (According to state corrections data, about 66 percent of those prisoners come from New York City's boroughs). When legislative district lines are drawn around the prisons, they create what Wagner calls a "phantom" population that violates the constitutional "one person, one vote" rule. For example, if a district contains 10,000 people and 2,000 of them are prisoners (who are counted in the Census, but have no say in elections) the interests of the remaining 8,000 people form their elected official's mandate.

By contrast, in New York City, which has few state prisons, almost all 10,000 people in a district will create the elected official's mandate. The situation is inherently unequal, analysts say. Since the votes of 8,000 people upstate (representing a community that is considered to have a population of 10,000) are "equal" to the votes of 10,000 people downstate, each upstate voter's vote "weighs" more. That disparity apparently violates the "one person, one vote" concept.

"Anybody who cares about the state of democracy should care about this," says Tracy Huling, a criminal justice researcher who has studied the impact of prisons on rural towns and produced a documentary on the trend titled, Yes, In My Back Yard.

"1 think people in upstate New York who don't have prisons should care about this because it's skewing upstate priorities," Huling says, referring to a tendency for prison towns to elect "tough-on-crime" politicians who back policies that increase incarceration rates.

"People who want some kind of reform in criminal justice need to care about this because the way in which the politics of this affects public policy in criminal justice has become almost obvious," adds Huling.

Not only that, it may be illegal. Wagner cites a 19th century case in which the New York State Court of Appeals upheld the conviction of a man on a charge that he had tried to register to vote from a city jail. The 1894 case, New York State v. Cady, held that Michael Cady, who intentionally got arrested repeatedly and convicted for vagrancy to maintain his residence at a city facility, could not list a prison as his residence because it violated the state constitution.

"The domicile or home requisite as a qualification for voting means a residence which the voter voluntarily chooses and has a right to take as such, and which he is at liberty to leave, as interest or caprice may dictate, but without any present intention to change it," wrote the court in its decision upholding the conviction.

Gary King, a professor of government at Harvard University who is a redistricting expert, says the disparity between state law that says a prison cannot be a residence and the practice, for redistricting purposes, of counting those prison cells as homes could be the grounds for litigation. The practice of counting pris-oners as residents of those towns will likely create more Republican districts, he adds.

Laughlin McDonald, Atlanta-based director of the American Civil Liberties Union's Voting Rights Project, says a 1966 Supreme Court ruling in the case of Burns v. Richardson held that states do not have to use the Census for redistricting. But most do it anyway.

"I don't know a jurisdiction that doesn't use those figures," McDonald says, adding that a state might opt to do its own census, accounting for the prisoners as residents of the places from which they come. But that would add another layer of bureaucracy and strain many state's budgets.

"There's no perfect way to solve the problem. As a practical matter it would be enormously difficult to account for those transient [prison] populations," McDonald says. He cites military personnel, college students and nursing home residents as other populations that are counted the same way. The distinction, though, may lie in the fact that prisoners have little real political representation and, in all but two states, Maine and Vermont, cannot vote.

"A person's body carries with it a certain amount of political representation," says Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, a Duke University undergraduate who authored "Inmate Enumeration Methods and Legislative Districting in the United States." The study tracked the same patterns as Wagner did in his New York study. For example, her research shows that political power drawn from cities such as Miami, Jacksonville and Tallahassee is transferred to rural communities that house prisons. "And when you move people's bodies, they carry with them that political representation," she adds.

Stinebrickner-Kauffman says that an alternative method, which would not cause a dilution of minority voting strength, would be to have prisoners fill out the census questionnaires using their home addresses. Census rules currently require prisoners to use the prison as their home address. "I don't think it would be messy" she says.

Stinebrickner-Kauffman and Wagner cite the Constitutional Convention of 1787, at which the "3/5ths Clause" was introduced. That was the measure that allowed Southern slave-holding states to count each slave as 3/5ths of a white person to prevent those states from being outvoted in the Electoral College. They say that way of counting has an eerie historical parallel with the same "pernicious" effect as the redistricting issue: More than 200 years later, Black and Latino populations still count less than their white counterparts.

"There has been systematic suppression and reduction of Black political power in the United States," Stinebrickner-Kauffman says. She adds that the quickly rising incarceration rate of the late 20th century (though it has recently slowed) combines with a method of apportioning political power implemented at the nation's birth to Blacks' political detriment.

They are reminiscent, she says, of the poll tax, literacy test and grandfather clauses that served as barriers to Black enfranchisement in the post-reconstruction period. Stinebrickner-Kauffman cites the words of Virginia Senator Carter Glass, who a century ago stated his explicit endorsement of such measures.

"Discrimination! Why that is precisely what we propose," Glass said at the 1901 state Constitutional Convention. "That, exactly, is what this Convention was elected for to discriminate to the very extremity of permissible action under the limits of the Federal Constitution, with a view to the elimination of every Negro voter who can be gotten rid of legally, without materially impairing the numerical strength of the white electorate." Such procedures were outlawed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

"This is one of those things that, if it were happening to white people, would be stopped.' says Stinebrickner-Kauffman. "But since it's happening to minority groups that don't have [much] political power, it hasn't been stopped."

Other observers say the problem highlights a larger structural issue of the danger of conducting "winner-take-all" elections, where power is not divided up proportionally to how the electorate voted.

"Most countries and democracies use a proportional voting system so that a certain percentage of the vote translates into that same percentage in the legislature, and it doesn't matter so much where you live," says Eric Olson, deputy director of the Center for Voting and Democracy in Takoma Park, Md. "If we had a proportional voting system, this wouldn't be an issue," he adds.

The Cost of Disenfranchisement

Olson's group has worked on various issues including proportional representation, redistricting and felon disfranchisement in Maryland, having backed a successful drive to make it more difficult for felons to lose their voting rights. This year, an initiative was enacted into law that allows the state to permanently revoke the right to vote only of two-time violent offenders. The previous law barred any two-time felon from voting.

States with the greatest number of disenfranchised felons

About 4 million Americans have lost the right to vote, 1.4 million of them are Black men

| State | Total felons | Percent of total* | Black men | Percent of Black men |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Florida | 647,100 | 5.9 | 204,600 | 31.2 |

| Texas | 610,000 | 4.5 | 156,600 | 20.8 |

| California | 241,400 | 1.0 | 69.500 | 8.7 |

| Alabama | 241100 | 7.5 | 105,000 | 31.5 |

| Mississippi | 145,600 | 7.4 | 81,700 | 28.6 |

| New Jersey | 138,300 | 2.3 | 65,200 | 17.7 |

| Maryland | 135,700 | 3.6 | 67,900 | 15.4 |

| Georgia | 134,800 | 2.5 | 66,400 | 10.5 |

| New York | 126,800 | 0.9 | 62,700 | 6.2 |

| Tennessee | 97,800 | 2.4 | 38,300 | 14.5 |

| North Carolina | 96,700 | 1.8 | 46,900 | 9.2 |

In the state of Maryland, according to recent figure, there were nearly 136,000 people who were disfranchised. Fifteen percent of Black males in the state -- 67,900 -- have lost the right to vote.

Eight states -- Alabama, Florida. Iowa. Kentucky, Mississippi. Nevada. Virginia and Wyoming -- permanently bar ex-felons from voting without exception. Maryland and Arizona permanently disenfranchise those convicted of a second felony, and Tennessee and Washington state permanently bar from voting felons convicted before 1986 and 1984, respectively, according to the Sentencing Project, a criminal justice policy think tank in Washington, D.C. Other states restore voting rights upon completion of sentences or parole, though some require an application process.

Federal prisoners are barred from voting during their terms of incarceration. Upon release, they are subject to the laws of the states where they live, says Marc Mauer, an analyst at The Sentencing Project.

About 4 million people in the United States, including 1.4 million Black men (13 percent of the adult male Black population) have currently or permanently lost their right to vote as a result of a felony conviction, according to Sentencing Project data. The center, which teamed up with New York City-based Human Rights Watch to produce the 1998 report "Losing the Vote: The Impact of Felony Disenfranchisement Laws in the United States," could not provide figures for disenfranchised women.

Eight states -- Alabama, Florida. Iowa. Kentucky, Mississippi. Nevada. Virginia and Wyoming -- permanently bar ex-felons from voting without exception. Other states restore voting rights upon completion of sentences or parole, though some require an application process.

Malcolm Young, executive director of the Sentencing Project, says the result of the election in Florida is perhaps the most stark indicator of the impact of felon disenfranchisement: It literally decided who would occupy the White House.

"There's no question that the election in Florida would have been different had there not been felon disenfranchisement," he says, adding that Florida disenfranchises more people than any other state. "There can't be any question about it."

The irony of the result, Young adds, was that Democrats who most often present themselves as champions for the poor and minorities allowed the very policies that incarcerated unprecedented numbers of those groups to flourish during the eight years of the Clinton administration, a period which saw population of Black women in prisons and jails increase by almost 50 percent.

"Drug law policies that contribute to the racial disparity were just as much a result of the war on drugs in the Clinton administration as they were under the first Bush administration which began it," says Young. "In a crude sense, vice president [Al Gore] ate a bitter pill of his own administration's making."

Felon disenfranchisement has roots in the societies of ancient Greece and Rome and has been policy in one form or another in the United States since its founding. But southern states began to broaden the offenses under which the disenfranchisement law could be applied in the post-reconstruction period between 1890 and 1910, according to Laughlin McDonald of the ACLU's Voting Rights Project. They included, in South Carolina, for example, crimes that lawmakers believed Blacks tended to commit more than whites, such as "thievery, adultery, wife-beating, housebreaking and attempted rape," he says.

Detaining For Dollars

Studies of the impact of incarceration rates and elections dove-tail with other analyses that show the same counting method cheats minority communities by steering a pool of federal funds based on the census into prison-hosting towns and away from prisoner-exporting communities.

Federal agencies that administer housing grants and anti-poverty funding programs tend to rely on Census data to determine which communities are most needy. Since most prisoners make little if any money, when they are counted in the Census they inflate the population (and more specifically the minority population) of host towns and deflate their income level.

That makes the town appear "poorer" on applications for funds and thereby more competitive in the race for some $2 trillion Census-based dollars that will be distributed by the federal government in this decade, says Haling, the New York filmmaker and researcher. Legislators working to secure some of those dollars launched creative campaigns to use rising captive populations to their advantage.

Arizona passed a law allowing cities to annex prisons on government-owned or unclaimed land within 15 miles of their borders to maximize aid doled out on a per capita basis. This sparked a battle between two towns, Buckeye and Gila Bend, to claim 4.150 prisoners as their own, says Holing, who followed the row.

Buckeye, which won the battle, stands to gain about $600 per prisoner every year, which amounts to more than $10 million in funds tied to the Census over the decade, she says.

Arizona's prison population is 55.3 percent minority, while the town of Buckeye is 72.5 percent white.

In an effort to counteract this trend, Rep. Mark Green (R-Wis.) sponsored a bill to allow Wisconsin prisoners housed in other states to be counted in the 2000 census as Wisconsin residents. Despite backing from lawmakers in other "prisoner-exporting" states, the bill failed. Green says Wisconsin could lose between $5 million and $8 million each year.

Even the most cynical analysts are loath to say that the manner in which prisoners are counted is designed to disenfranchise and, or divert foods from the nation's urban centers. They say almost universally that the consequences are significant in their effect on certain racial groups, but that the effects are unintentional.

Many activists are working to change laws that allow it to happen, using such tactics as the redistricting challenges, which McDonald of the ACLU says are pending in many southern states.

All of the challenges are race-based, as is the one pending in Chelsea, Mass., and launched by Brenda Wright's Boston-based group, the National Voting Rights Institute. Groups such as the NAACP have offered alternative redistricting plans in some states and filed litigation in others.

Other observers, such as researchers Stinebrickner-Kauffman and Wagner, recommend an overhaul of or an exception to the counting method since communities are politically and materially disadvantaged by the currently used counting method. And activists like Olson are working to redesign a political system that they see as inherently flawed from the start with its "winner-take-all" approach.

"The prison system has managed to entrench itself into our economic, political and social structure, so much so that making the decisions as to whether or not to continue to expand or contract it have been distorted," says Wagner.

"It's subverting the democratic process."

Zachary R. Dowdy is a reporter at Newsday in New York.