For families of incarcerated dads, Father’s day comes at a premium

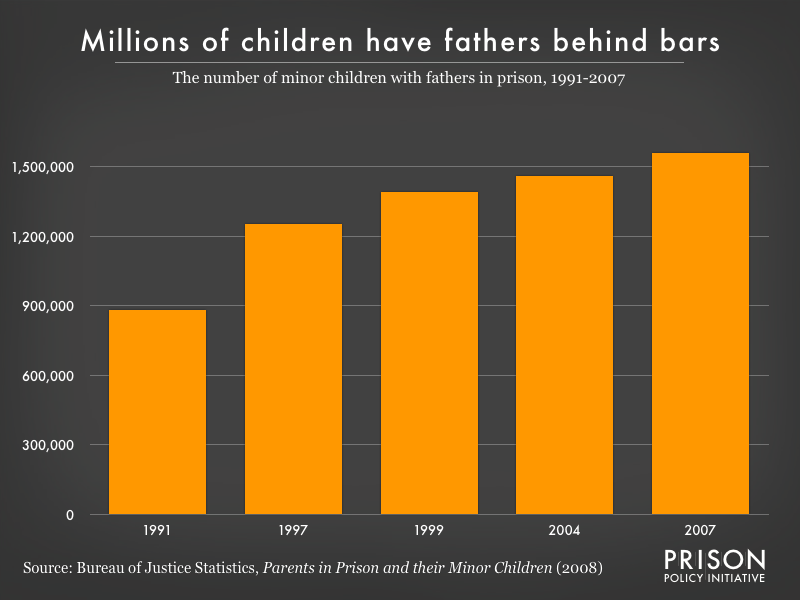

Over 1.5 million children have a father incarcerated in prison today. As Father's day approaches, millions of children will be without their fathers, and without the ability to pay the outrageous fees associated with speaking to them. State lawmakers should take the initiative to better regulate prison telecom companies, and most importantly, reduce the number of incarcerated people.

by Lucius Couloute, June 13, 2017

In the U.S., we often hear ‘you do the crime, you do the time.’ But incarceration isn’t just an individual-level problem, it affects entire networks of people. This Father’s Day I’d like to bring attention to the pernicious consequences of parental incarceration and the exploitive ways in which private telecom companies profit from the separation of families.

Crime has been declining for decades, yet the number of children with a father in state or federal prison is now over 1.5 million. If we include jails, 1 out of every 28 children now has an incarcerated parent. And the latest estimates suggest that Black and Hispanic children are up to six times more likely to have an incarcerated parent than their white peers.

From 1991 to 2007 the number of minor children with a father in state or federal prison increased 77%. In a separate graph we detail the growing number of fathers in prisons.

From 1991 to 2007 the number of minor children with a father in state or federal prison increased 77%. In a separate graph we detail the growing number of fathers in prisons.

Victims of a war waged – largely on poor communities of color – long before they were born, over-criminalization forces children to contend with a vast array of barriers that prevent upward economic mobility. Parental incarceration is associated with an increased risk of childhood poverty, health problems, school suspension and expulsion, and can be a source of stigma for children as they navigate the world around them. During a period when bipartisan support for reform appears to be in flux, it’s important to remember that young lives are at stake when we over-incarcerate.

And as if the forced separation of fathers from their loved ones wasn’t enough, telecom providers have found a way to benefit – and indeed profit – from parental incarceration. At a time when phone companies provide unlimited long distance calling for people like me and you, it can cost an incarcerated person and their family up to $24.95 for a single 15-minute in-state phone conversation. These exorbitant costs help explain why over $1.3 billion a year goes to the prison telephone industry.

A more recent development has been the growth of the video visitation industry; where local jails collude with private companies to charge up to $1.50/minute for low quality offsite video conferencing services (not including any additional fees that get tacked on for good measure). As jails across the country implement this technology they tend to scale back or eliminate in-person visits altogether, all the while receiving kick-backs from the private, for-profit telecom companies.

The exploitative practices of the prison communication industry – which penalize families for trying to stay in touch – amounts to a kind of regressive taxation. In this case, the profits come disproportionately from poor people already struggling with the absence of a loved one. From both a policy perspective, and from the perspective of families, replacing in-person visits with poorly functioning and expensive video visitation is unacceptable.

So on this Father’s Day, millions of children will be without their fathers, and without the ability to pay the outrageous fees associated with speaking to them. I hope that by the time Father’s Day comes around next year, state lawmakers take the initiative to better regulate prison telecom companies, and most importantly, reduce the number of incarcerated people.