New report, Getting Back on Course, shows that prison permanently hinders education

Our criminal justice system isn’t just sending people from school to prison – it’s locking them out of education altogether.

October 30, 2018

It’s common knowledge that the U.S. criminal justice system funnels youth from schools to prisons – but what happens after that? How many people, for instance, are able to finish high school during or after prison? A new report from the Prison Policy Initiative breaks down the most recent data, revealing that incarcerated people rarely get the chance to make up the education they’ve missed.

The data shows how incarceration, rather than helping people turn their lives around, cements their place at the bottom of the educational ladder:

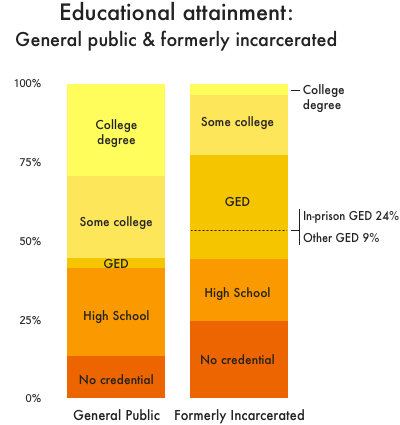

- 25% of formerly incarcerated people have no high school credential at all – twice as many as in the general public.

- Formerly incarcerated people are most likely to finish high school by way of GED programs, missing the benefits of a traditional four-year education.

- Less than 4% of formerly incarcerated people have a college degree, compared to 29% of the general public.

The unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people is a staggering 27%, the Prison Policy Initiative previously found. This rate differs by education level. For those returning home from prison without educational credentials, it is “nearly impossible” to find a job:

- Formerly incarcerated people without a high school diploma or GED face unemployment rates 2 to 5 times higher than their peers in the general public. These rates differ by race and gender, ranging from 25% for white men to 60% for Black women.

- The number of “low-skill” jobs requiring only a high school credential has dropped since 1970, leaving many formerly incarcerated people with even fewer job prospects than ever before.

- Even as college degrees become critical to finding a job, most incarcerated people cannot access degree-granting programs, Pell Grants and federal student loans.

“We need a new and evidence-based policy framework that addresses K-12 schooling, prison education programs, and reentry systems,” report author Lucius Couloute concludes. He offers four far-reaching recommendations aimed at increasing access to educational opportunities, for both incarcerated people and youth at risk.

Today’s report is the third and final part of a new series from the Prison Policy Initiative, focusing on the struggles of formerly incarcerated people to access employment, housing, and education. Utilizing data from a little-known and little-used government survey, Couloute and other analysts describe these problems with unprecedented clarity. In these reports, the Prison Policy Initiative recommends reforms to ensure that formerly incarcerated people – already punished by a harsh justice system – are no longer punished for life by an unforgiving economy.