New report shows mass incarceration doesn’t stop at the prison walls

Report ranks states' use of “correctional control” to provide the full picture of mass supervision in the U.S.

May 10, 2023

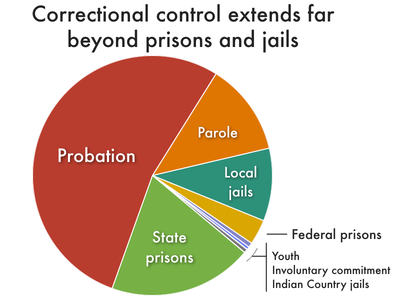

1.9 million people are behind bars in the U.S., but this number doesn’t capture the true reach of the criminal legal system in the country. In a new report, Punishment Beyond Prisons: Incarceration & Supervision by state, the Prison Policy Initiative shows how in America, the overuse of probation and parole, along with mass incarceration, has ensnared a staggering 5.5 million people in a system of mass punishment and correctional control.

Punishment Beyond Prisons shows the full picture of correctional control in the country, with a particular focus on the overuse of probation and parole. Altogether, an estimated 3.7 million adults are under community supervision (sometimes called community corrections) — nearly twice the number of people who are incarcerated in jails and prisons combined. The vast majority of people under supervision are on probation (2.9 million people), and over 800,000 people are on parole. The report explains how people supervised through these programs live under a harsh set of rules that others do not, and that these rules often lead them back to incarceration. In addition, it provides over 100 easy-to-understand pie charts that show how many people are behind bars or under some form of community supervision in each state.

“Probation and parole are often talked about as a more ‘lenient’ approach than incarceration, but these programs are insidiously designed to extend the reach of mass punishment beyond the prison walls,” said Leah Wang, author of the report. “To understand the full scale of the carceral system in a state, you have to look at how — and how often — probation and parole are used, and whether they strengthen our communities or simply serve as a revolving door to prison.”

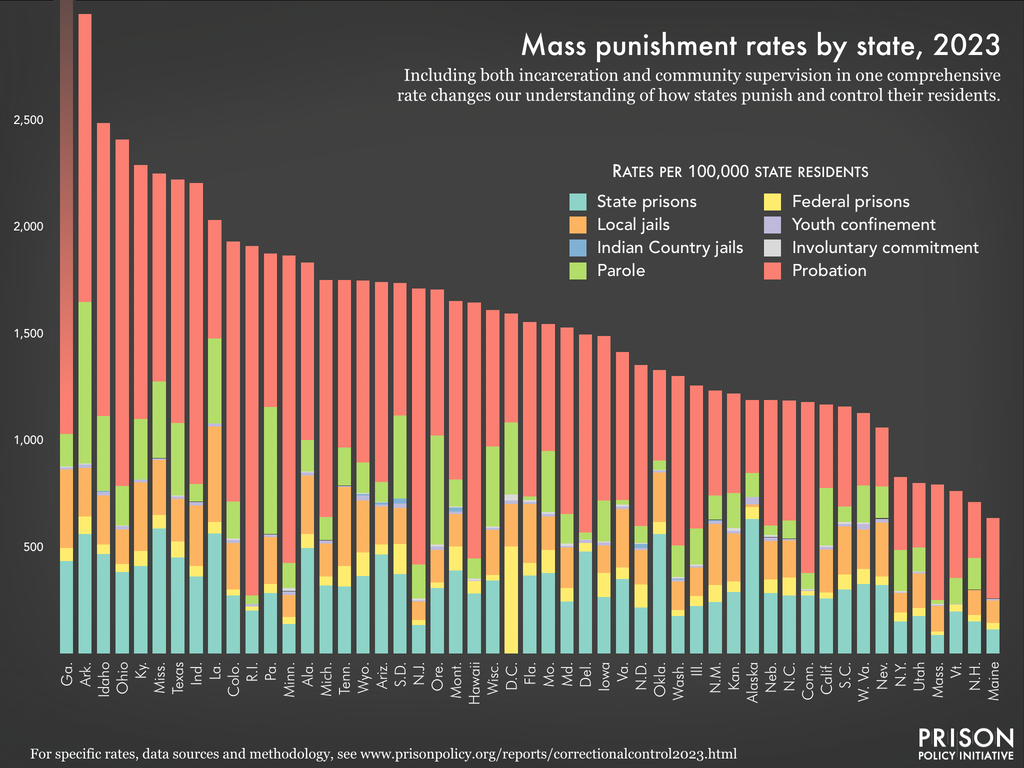

Punishment Beyond Prisons provides a chart that ranks states by their use of correctional control, allowing policymakers, advocates, and journalists to better understand the scope of their state’s system of mass supervision, and how it stacks up against others.

Looking closely at state variations in the use of various forms of correctional control reveals just how differently states mete out punishments; in particular, states vary tremendously in their use of community supervision. For example, the report shows:

- Massachusetts and Utah have nearly identical rates of overall correctional control, but 68% of people in Massachusetts’ punishment systems are on probation, and only 28% are incarcerated in state and federal prisons and local jails. In Utah, on the other hand, only 39% are on probation, and a much larger share (46%) are incarcerated.

- Minnesota has a larger share of its population under correctional control than Alabama does, even though a resident of Minnesota is far less likely to be incarcerated than a resident of Alabama.

- Because of its large probation system, Rhode Island’s total correctional control rate rivals that of Louisiana, one of the most notoriously punitive states in the country (with the nation’s highest incarceration rate).

Probation and parole are important tools that can reduce the number of people in prisons and jails. However, too often, community supervision sets people up to fail, by forcing them to comply with vague and wide-ranging rules and fees, and failure to comply can mean going to jail or prison. These “failures” are so common that less than half (44%) of people who “exited” parole or probation in 2021 did so after successfully completing their supervision terms, many of the rest were reincarcerated for “technical violations,” such as missing a check-in or nonpayment of fees — things that are not crimes in any other circumstance.

“When used properly, probation and parole can be tools to keep people out of prisons and jails,” said Leah Wang. “Instead of burdening people with onerous requirements that make it more — not less — difficult for them to build stable lives, state and local leaders should focus on connecting people with the services and supports that help them meet their social, economic, and health needs.”

The report concludes by highlighting successful reforms that have improved probation and parole and reduced the number of people behind bars. For example, California instituted new time limits on probation terms that are projected to save the state $2.1 billion. New York enacted major legislation intended to reduce unnecessary incarceration for noncriminal, “technical” offenses of parole, resulting in hundreds of people becoming immediately eligible for release and thousands more no longer living with arrest warrants for these technical offenses. Additionally, Louisiana restored parole eligibility to certain people and reduced the number of years some people must wait to be eligible for consideration.

The full report is available at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/correctionalcontrol2023.html