Reaching too far: How Connecticut’s large sentencing enhancement zones miss the mark

by Aleks Kajstura, March 28, 2014

Executive Summary

Connecticut, like most states, attempts to steer drug activity away from places where children may be present by mandating extra penalties for drug-related offenses committed in certain geographic areas. Connecticut’s sentencing enhancement law creates enhanced penalty zones that extend 1,500 feet from schools, day care centers, and public housing. The law creates additional mandatory penalties for drug-related offenses that are committed within the zones.

In practice, however, fundamental flaws with Connecticut’s law prevent it from actually protecting children from drug activity. This report shows that the law doesn’t work, it cannot possibly work, and that it creates an unfair two-tiered system of justice based on a haphazard distinction between urban and rural areas of the state.

The biggest obstacle to efficacy is that the zones are too expansive to serve as functional deterrents. The law attempts to mete out increased penalties in select protected zones to drive undesirable activity away from the designated protected places. At 1,500 feet, however, these zones are so large that they blanket entire cities, leaving no uniquely protected areas. In essence, when everywhere is special, nowhere is special.

In addition to failing to achieve its goal of creating protected spaces, the law creates an “urban penalty” that increases the sentence imposed for a given offense simply because it was committed in a city rather than in a town.

Because schools, day cares, and public housing are scattered throughout densely-populated urban communities, most areas in Connecticut cities are covered by zones that trigger the extra mandatory minimum sentence in addition to the base penalty for the underlying offense. In more sparsely-populated towns, very little area is covered by these zones, and people facing drug charges in these non-urban areas are subject only to the base penalties for the underlying offense. Connecticut’s sentencing enhancement zone policy essentially increases the sentence for offenses committed within cities, leaving a lower penalty for offenses committed in towns.

The most comprehensive solution is for the Connecticut legislature to repeal the enhancement zones, and instead rely on the already-existing laws that give additional penalties for involving children in drug activity. Barring repeal, there are several ways to modify the geographic scope of the law to more closely meet the legislature’s goal of protecting children by deterring drug activity away from certain places. The most basic change would be to reduce the distance of the zones to 100 feet of protected places. This modification would create smaller zones containing discrete and identifiable protected spaces, and would remedy the urban penalty that results from the overlapping superzones created by the current statute.

Introduction

Connecticut is one of 48 states1 that have geography-based penalties for certain drug-related offenses. First enacted in reaction to the “crack epidemic” concerns of the 1980’s, these laws create additional mandatory penalties for drug-related offenses that are committed within a certain distance of places such as schools. The goal of these “sentencing enhancement zone laws” is to steer people engaging in drug activity away from children.

Connecticut’s law, however, is fundamentally flawed. The research in this report shows that this law doesn’t work, it cannot possibly work, and that it creates an unfair two-tiered system of justice based on a haphazard distinction between urban and rural areas of the state.

The Connecticut legislature passed the state’s sentencing enhancement law in 1987 - and expanded it in 1989, 1992 and again in 1994 - to further the legitimate goal of keeping drug activity away from children. But good intentions alone do not make good law. Several inaccurate assumptions prevent Connecticut’s law from actually keeping illegal drug activity away from children.

The biggest problem is that the zones are too expansive to be effective, and the subsequent amendments to the original law only made the problem worse. The 1987 law created a two-year minimum mandatory sentence enhancement for convictions of drug sales within 1,000 feet of a school’s property line, to be added on top of the sentence served for the underlying offense. In 1989, just two years after the original law was passed, the legislature amended it to increase the minimum sentence from two to three years. In 1992 the legislature added public housing projects to the list of areas that trigger the creation of zones, and again expanded the zone length from 1,000 feet to 1,500 feet. Two years later, licensed child day care centers were added to the list of places that trigger zone creation.2 Today, Connecticut is among the states with the largest zones in the country, along with Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Carolina.

Connecticut’s zone law fails to keep illegal drug activity away from children

On the most basic level, Connecticut’s sentencing enhancement law fails to deter drug activity away from schools, day cares, and public housing. For example, a 2005 Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee evaluation found that “in the majority of the sample drug cases the illegal drug activity occurred in a housing project in which the arrestee lived or a private residence in a ‘drug-free’ zone. This is consistent with drug crime research that shows persons arrested for drug crimes tend to offend in the vicinity of their residences.”3

Other states with similar sentencing enhancement zone policies have found similar results. A study of a Massachusetts law, which has since been reformed, found that drug dealing was actually denser inside school zones than outside them.4 The New Jersey Commission to Review Criminal Sentencing, examining arrests near schools before and after their legislation’s passage, came to a similar conclusion: instead of dropping as offenders were deterred, the general trend of arrests inside the zones was “strongly upward.”5

Connecticut’s sentencing enhancement zones cannot deter drug activity because they are both pervasive and imperceptible on the ground.6 The Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee found that “[p]articularly in larger municipalities, ‘drug-free’ zones tend to overlap. In many municipalities, the total ‘drug-free’ zone area is irregularly shaped. Drug sellers and users and others (e.g., students, parents, municipal officials) are unlikely to be able to identify whether they are actually in a ‘drug-free’ zone.”7 And so the zones end up having no bearing on drug-related activity.

Research shows that Connecticut’s sentencing enhancement zone law only serves to arbitrarily increase the time people convicted of drug offenses must spend in prison without any evidence that their underlying offense actually endangered children. In fact, the Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee looked at a sample of 300 sentencing enhancement zone cases, and found only three cases that involved students, none of which involved adults dealing drugs to children. The Committee explained: “In one case, a police officer observed a group of students sitting outside the school smoking marijuana. In two cases, school officials called police to the school in response to information that students were selling drugs on school property. Except for those three cases in which students were arrested, all arrests occurring in “drug-free” school zones were not linked in any way by the police to the school, a school activity, or students. The arrests simply occurred within “drug-free” school zones.”8 All of the other 297 cases in the legislature’s sample involved only adults.

Connecticut’s sentencing enhancement law cannot possibly work as designed

Among the law’s many flaws, one is particularly fatal to its efficacy: 1,500-foot zones are absolutely too large.

One person simply cannot influence another from 1,500 feet away. According to the Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee, “the General Assembly intended to send a strong message that it was attempting to protect children from drugs.”9 It is likely that legislators assumed that the 1,500-foot distance was small enough that any person selling within it intended to sell to children. A series of experiments conducted by the Prison Policy Initiative in 2007 proved that even at shorter distances that assumption was clearly flawed.10 Furthermore, a survey conducted by the federal government, revealed that children who use drugs most frequently use marijuana,11 and most often obtain it from friends, not strangers.12

Furthermore, in order for the sentencing enhancement law to be an effective deterrent, a person who is committing a drug offense must be able to identify an area that does not trigger the additional penalty and relocate to that place before engaging in illegal drug activity.

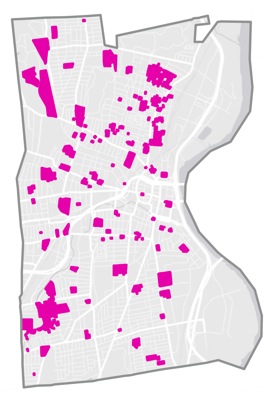

In Connecticut, however, the law fails to create a meaningful deterrent effect because overlapping superzones cover virtually entire cities. In these regions, a person engaging in illegal drug activity cannot leave one zone area without inadvertently entering another. Our analysis reveals that 94% of Hartford’s residents, 93% of New Haven’s residents, and 92% of Bridgeport residents live in areas covered by a sentencing enhancement.

Figure 1. Overlapping sentencing enhancement superzones blanket Hartford, covering 94% of the city’s residents.

Sentencing enhancement zones disproportionately cover urban cities due to two factors: urban areas are densely built and populated, and so cities contain many of the types of places that trigger the creation of the extensive 1,500-foot zones. For example, Hartford has as many schools and day care centers as 42 other Connecticut municipalities have, combined. The legislature’s 1992 amendment to add public housing to the list of locations that trigger zones makes this urban effect even more dramatic.

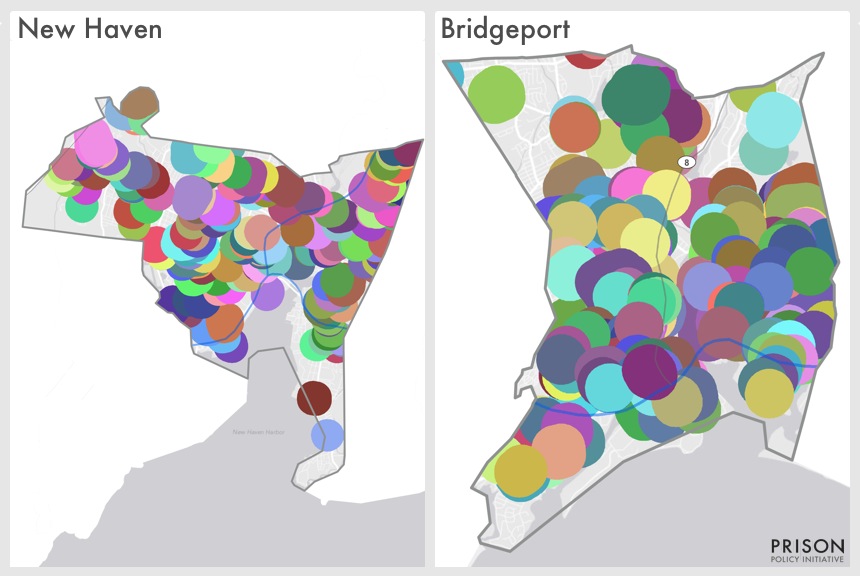

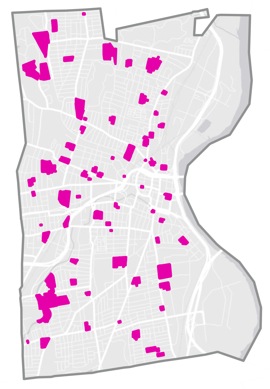

A similar picture emerges in New Haven and Bridgeport:

Figure 2. Overlapping sentencing enhancement superzones blanket New Haven and Bridgeport, covering 93 and 92% of the cities’ residents, respectively.

Connecticut’s sentencing enhancement zone law was passed to create special protective zones around areas where children may be present. But the law created superzones that cover entire cities, and when everywhere is special, nowhere is special. In practice, Connecticut’s school zone law fails to protect children and instead arbitrarily increases the sentence served for drug convictions based solely on where the offense occurred.

Harmful side effects

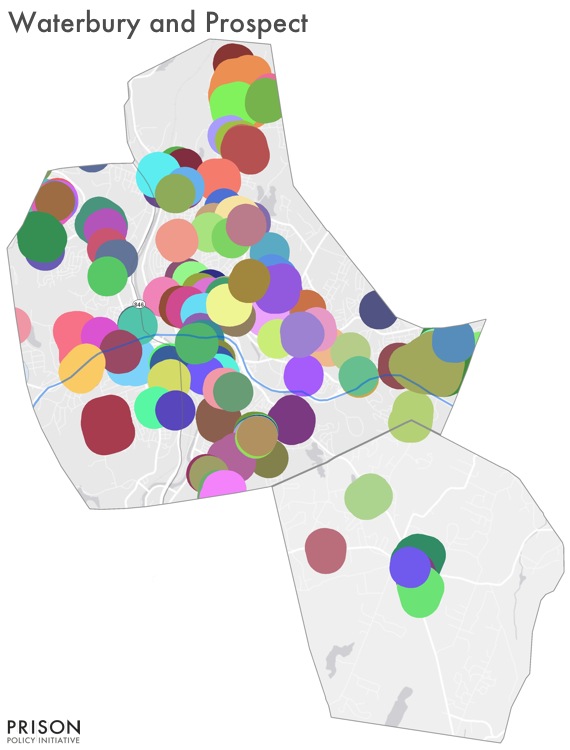

Our maps of sentencing enhancement zones in the neighboring municipalities of Waterbury and Prospect illustrate the law’s disproportionate impact on large cities. In Waterbury, overlapping superzones cover large swaths of the city, disproportionately subjecting urban residents to harsher sentences. This “urban penalty” is clear when the map is compared with Prospect, a neighboring town to the south where residents are subject to only a few sentencing enhancement zones:

Figure 3. A comparison of the City of Waterbury (top), and its neighbor, the Town of Prospect (bottom) reveals the stark difference in the law’s application between urban and suburban or rural settings.

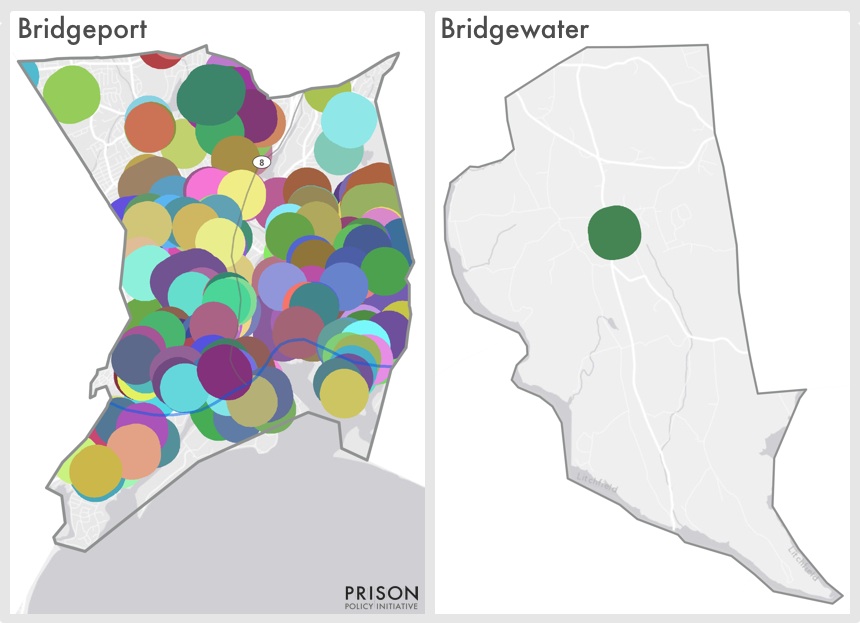

A similar discrepancy in zone application emerges when we compare the City of Bridgeport to the Town of Bridgewater:

| Population Covered by Zones | Population Outside the Zones | |

|---|---|---|

| Bridgeport | 92% | 8% |

| Bridgewater | 8% | 92% |

Figure 4. Overlapping sentencing enhancement superzones blanket Bridgeport, covering 92% of the city’s residents while Bridgewater contains just one zone, covering 8% of the town’s residents.

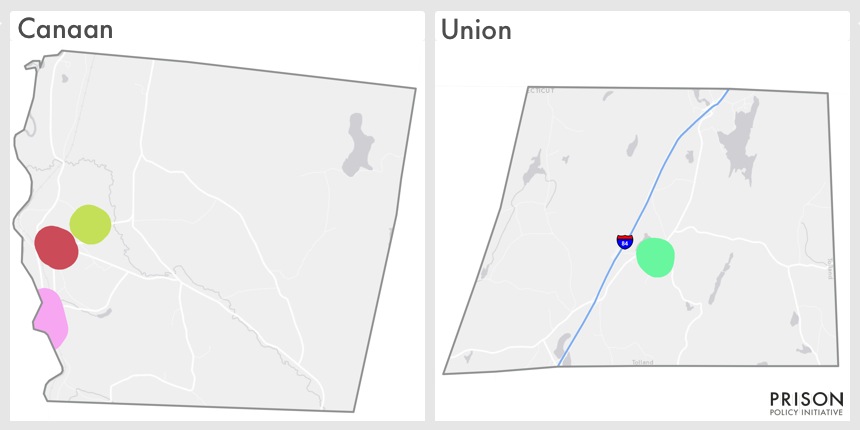

Other rural areas in Connecticut are similarly minimally affected by the state’s sentencing enhancement zone law:

Figure 5. The rural towns of Canaan and Union serve as a contrast to the law’s application in urban settings.

Denies equal access to justice for urban residents

As the above maps demonstrate, Connecticut’s sentencing enhancement zone law effectively imposes a harsher penalty for the same crime depending on whether the person who committed it lives in a large city or a small town. In practice, the law’s effects are even more insidious: the law increases pressures on urban residents, but not rural ones, to plead guilty solely to avoid the enhanced penalty.

The threat of a mandatory minimum sentence such as the zone penalty increases the pressure on a defendant to plead guilty in order to avoid the automatic prison time. That pressure is especially strong in drug-related cases.13 Largely as a result of these pleas, 90% of charges for drug-related offenses that are subject to mandatory minimums in Connecticut lead to convictions of a lesser charge.14 The law effectively pressures urban residents to plead guilty in order to get a chance at the same sentence as is given to rural residents who go to trial.

Mandatory minimum sentences, such as those created by Connecticut’s sentencing enhancement zone policy, warp the criminal justice system by steering cases away from trial and toward plea agreements. By creating mandatory minimum sentencing enhancement zones in disproportionately urban areas,15 the legislature has created a two-tiered system of justice.

Recommendations

Figure 6. Illustration of a reduction to 100-foot zones, in Hartford. Reducing the size of the zones to 100 feet creates more effective protected places in cities.

Figure 7. Illustration of 100-foot zones around schools and day care centers, but not public housing, in Hartford.

The most comprehensive solution is for the Connecticut legislature to repeal the enhancement zone portions of the law,16 and instead rely on the already-existing laws that give additional penalties to people who are actually selling drugs to kids.17

Barring repeal, there are several ways to modify the geographic scope of the law to better tailor it to successfully meet the legislature’s goal of protecting children.

Making the zones smaller. Reducing the size of the zones to within 100 feet of a school or other place would make the law more effective.18 The zones could be easier to identify and avoid, enabling the legislature’s desired deterrent effect to take place - moving drug activity away from schools.

Preventing offenses that take place in private residences from triggering the enhanced penalty. Currently, and under my proposed 100-foot zones, the law still increases penalties for those who happen to live inside a sentencing enhancement zone. Therefore, another geographic solution to consider is to exclude drug offenses that take place in private residences, out of view of the public.19

Reducing the types of places that trigger the creation of sentencing enhancement zones. Removing housing projects from the list of places, for example, would help to diminish the urban penalty effect.

Methodology

This report relies on an analysis of the areas within 1,500 feet of schools, day care centers and public housing in 8 cities and towns. Critically, and in contrast to past studies, this report is based on:

- The property lines of the protected places (schools, day care centers, and public housing) as required by statute (Conn. Gen. Stat. § 21a-278a(b)) which says the distance should be measured from the “real property” of the protected places.20 Previous analyzes by Connecticut’s Office of Legislative Research identified this as the preferred methodology but for practical reasons had to make their maps by measuring from a single point within each protected area as opposed to measuring in all directions from the boundary.

- The locations of public housing as required by the 1992 amendment (P.A. 92-82).

The data sources were:

- Schools: The University of Connecticut’s MAGIC GIS data library at http://magic.lib.uconn.edu/connecticut_data.html has a point shapefile produced in 2008 from the Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection showing the locations of “Connecticut Geographic Places”. We used only the public and private elementary, middle and high schools in this file and then individually applied each school to its specific property boundary.

- Day cares: The § 21a-278a(b) applies to “a licensed child day care center, as defined in section 19a-77, that is identified as a child day care center by a sign posted in a conspicuous place”. We used the list of licensed day care centers available from the Department of Public Health at http://www.ct.gov/dph/cwp/view.asp?a=3141&q=387164 to place individual day care center at specific parcel in each municipality. We assumed that each of these establishments has a “conspicuous sign”.

- Public housing: There is no statewide list of public housing in Connecticut, so we used a State Department on Aging list at http://www.ct.gov/agingservices/lib/agingservices/manual/appendix/housingauthoritiesfinal.pdf to identify the public housing authorities in each municipality. Housing Authorities in Hartford listed their housing project properties on their websites, but for other cities and towns we had to search by owner in the parcel database to identify which properties were public housing. We used the list of town public housing authorities prepared by the State Department of Aging to conclude that there is no public housing in the towns of Bridgewater, Canaan, Prospect, and Union.

- Property lines: We were able to obtain parcel layers from the cities of Bridgeport, Hartford, New Haven, and Waterbury. For the other towns, Prison Policy Initiative Executive Director Peter Wagner used aerial photography from ESRI and parcel data available on Google Maps to identify the likely property line of each location.

- The areas that are within 1,500 feet (and 100 feet, in the case of the recommendations section) of the protected places were mapped by Peter Wagner using ESRI ArcGIS Desktop 10.0.

- The number of residents in each town who live inside a sentencing enhancement zone was calculated by demographer Bill Cooper who overlaid the maps produced for this report over U.S. Census data. Where the zone maps did not precisely align with Census Bureau block maps, Bill Cooper apportioned the population of each block on the basis of area.

Acknowledgements

This report was supported by a generous grant from the Drug Policy Alliance Advocacy Grants Program and by the individual donors who help sustain the Prison Policy Initiative. The author extends special thanks to Leah Sakala, Policy Analyst, and Peter Wagner, Executive Director, for their research, mapping, and editing assistance, and to A Better Way Foundation for their years-long leadership on sentencing enhancement zone reform in Connecticut.

About the Author

Aleks Kajstura is the Legal Director at the Prison Policy Initiative. Among other publications, she co-authored two reports on sentencing enhancement zones in Massachusetts: The Geography of Punishment: How Huge Sentencing Enhancement Zones Harm Communities, Fail to Protect Children (2008), and Reaching too far, coming up short: How large sentencing enhancement zones miss the mark (2009). These reports helped lead Massachusetts to roll back their zone law in August 2012.

Footnotes

All states (and the District of Colombia) except for Montana and Wisconsin, have some form of sentencing enhancement zone law. For an overview of the laws see The Sentencing Project's Policy Brief: Drug-Free Zone Laws, available at http://sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/sen_Drug-Free%20Zone%20Laws.pdf. ↩

This turn of events is not entirely surprising. A review of reports issued by the Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee and the Office of Legislative Research reveals that the legislature has not had access to maps that show the full extent of their zones: e.g. “Each map shows the location of each elementary and secondary school, licensed child day care center, and public housing project. Around each location is a circle showing a 1,500 foot radius. Unfortunately, we do not have access to files showing property boundaries. Thus, the maps show the radius from the center of the property instead of from its property lines. As a result, the maps underestimate the areas within which enhanced penalties apply.” (OLR Research Report, Drug Crimes Near Schools, Day Care Centers, and Public Housing (2001), available at https://www.cga.ct.gov/2001/rpt/2001-R-0330.htm ); and “For the purposes of this mapping analysis, the “drug-free” zones were measured as 1,500 feet from a center point of the school, day care, or public housing project property… Staff did not have the data necessary to map a buffer around the school, day care center, and public house property parcels.… Clearly, this minimizes the amount of area within the “drug-free” zones.” (Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee, Mandatory Minimum Sentences (2005), available at https://www.cga.ct.gov/2005/pridata/Studies/Mandatory_Minimum_Sentences_Final_Report.htm ).

There was only one map I found to take property boundaries into consideration. That map was in use by the New Haven Police Department and was published in a 2001 report by the OLR Drug Sales Near Schools, Day Care Centers, and Public Housing Projects (available at https://www.cga.ct.gov/2001/rpt/2001-R-0016.htm ), but the map itself is no longer available through the OLR website - though a copy of it can be seen in the 2006 report Disparity by Design: How drug-free zone laws impact racial disparity - and fail to protect youth by the Justice Policy Institute, available at http://www.justicepolicy.org/research/1991. ↩

Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee, Mandatory Minimum Sentences (2005), available at https://www.cga.ct.gov/2005/pridata/Studies/Mandatory_Minimum_Sentences_Final_Report.htm ↩

William N. Brownsberger & Susan Aromaa (Join Together and Boston University School of Public Health), An Empirical Study of the School Zone Law in Three Cities in Massachusetts, p. 20 (2001). ↩

The New Jersey Commission to Review Criminal Sentencing, Report on New Jersey’s Drug Free Zone Crimes & Proposal for Reform, p. 26 (2005). ↩

The invisible line dividing areas in and outside of the enhanced penalty zones is indiscernible, as Arielle Sharma demonstrates in this Vine video available at https://vine.co/v/MMM63IDtZJd based on our maps of the enhancement zones in Hartford. ↩

Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee, Mandatory Minimum Sentences (2005), available at https://www.cga.ct.gov/2005/pridata/Studies/Mandatory_Minimum_Sentences_Final_Report.htm ↩

Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee, Mandatory Minimum Sentences (2005), available at https://www.cga.ct.gov/2005/pridata/Studies/Mandatory_Minimum_Sentences_Final_Report.htm ↩

Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee, Mandatory Minimum Sentences - Briefing (2005), available at https://www.cga.ct.gov/2005/pridata/Studies/Mandatory_Minimum_Senteces_Briefing.htm ↩

Aleks Kajstura, Peter Wagner, and William Goldberg, The Geography of Punishment: How Huge Sentencing Enhancement Zones Harm Communities, Fail to Protect Children, Sidebar “1,000 Feet is Further Than You Think”, available at http://www.prisonpolicy.org/zones/thousand_feet.html ↩

Department of Health and Human Services (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)), Results from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings, p. 1 (2005). ↩

Office of National Drug Control Policy, Marijuana Myths & Facts: The Truth Behind 10 Popular Misconceptions, p. 17 , available at https://www.ncjrs.gov/ondcppubs/publications/pdf/marijuana_myths_facts.pdf ↩

Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee, Mandatory Minimum Sentences, Table IV-3 (2005), https://www.cga.ct.gov/2005/pridata/Studies/Mandatory_Minimum_Sentences_Final_Report.htm ; and graphing the trends over time shows that as the number of arrests for mandatory minimum offenses increases, the number of convictions for the charge carrying a mandatory minimum decreases. (Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee, Mandatory Minimum Sentences, Figure IV-6 (2005), available at https://www.cga.ct.gov/2005/pridata/Studies/Mandatory_Minimum_Sentences_Final_Report.htm ). ↩

Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee, Mandatory Minimum Sentences, Table IV-3 (2005), available at https://www.cga.ct.gov/2005/pridata/Studies/Mandatory_Minimum_Sentences_Final_Report.htm ↩.

The 2001 mandatory minimum reforms establishing presumptive sentencing in Connecticut (PA 01-99, https://www.cga.ct.gov/2001/act/Pa/2001PA-00099-R00SB-01160-PA.htm (Under certain circumstances, allowing a lesser sentence for a charge that carries a mandatory minimum)) apply to the sentencing enhancement zone statute, but the equation doesn’t change much: the statute requires a 3 year minimum sentence, but even with presumptive sentencing the average sentence is 2.7 years average, versus an average of only 2 years for pleading to a lesser offence. (Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee, Mandatory Minimum Sentences, Table IV-4, available at https://www.cga.ct.gov/2005/pridata/Studies/Mandatory_Minimum_Sentences_Final_Report.htm ). ↩

Conn. Gen. Stat. §§ 21a-267, 21a-278a(b), and 21a-279(d) ↩

Conn. Gen. Stat. § 21a-278a(a) ↩

Connecticut Senate Bill 259, currently before the legislature, proposes a 200-foot distance, which is certainly a step in the right direction (a large improvement over the 1,500 feet currently in place). There is no simple mathematical formula for determining how a change in the distance would change the area covered by the zones, but it is analogous to the calculation for the area of a circle, where the area equals pi times the square of the radius (πr2). Cutting the radius in half cuts the area in the circle to just a quarter of the original area. Because the zones are based on the property lines, and not a single point, the formula doesn’t quite work the same, but it does give a good approximation of the scope of the change. ↩

Another way to tailor the law more closely to the legislature’s goal of protecting children is to limit the law’s application to hours when school is in session or other times when children are present. A few states have time-sensitive zones. For example, California limits applicability to when the school is open (Cal. Health & Safety Code § 11353.6), while Florida and Massachusetts identify specific hours of the day when the law applies (Fla. Stat. § 893.13 and, Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 94C § 32J, respectively). ↩

“Any person who violates section 21a-277 or 21a-278 by manufacturing, distributing, selling, prescribing, dispensing, compounding, transporting with the intent to sell or dispense, possessing with the intent to sell or dispense, offering, giving or administering to another person any controlled substance in or on, or within one thousand five hundred feet of, the real property comprising a public or private elementary or secondary school, a public housing project or a licensed child day care center, as defined in section 19a-77, that is identified as a child day care center by a sign posted in a conspicuous place shall be imprisoned for a term of three years, which shall not be suspended and shall be in addition and consecutive to any term of imprisonment imposed for violation of section 21a-277 or 21a-278. To constitute a violation of this subsection, an act of transporting or possessing a controlled substance shall be with intent to sell or dispense in or on, or within one thousand five hundred feet of, the real property comprising a public or private elementary or secondary school, a public housing project or a licensed child day care center, as defined in section 19a-77, that is identified as a child day care center by a sign posted in a conspicuous place. For the purposes of this subsection, “public housing project” means dwelling accommodations operated as a state or federally subsidized multifamily housing project by a housing authority, nonprofit corporation or municipal developer, as defined in section 8-39, pursuant to chapter 128 or by the Connecticut Housing Authority pursuant to chapter 129.” ↩

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.