It’s not just the franchise: Mass incarceration undermines political engagement

Contact with the criminal justice system impacts not only individual experiences of political participation, but also community-wide political engagement.

by Emily Widra, March 10, 2017

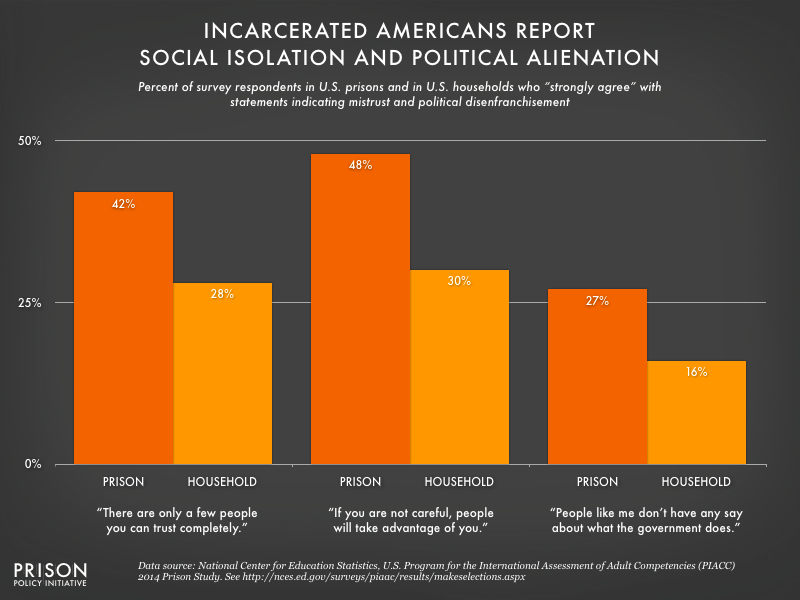

New research confirms what we already know happens to people when they are locked up. Their physical isolation leads to experiences of social isolation and their very real political disenfranchisement leads to a feeling of alienation from government. These psychological effects stay with people long after the physical and legal restrictions of their prison sentences end, affecting individuals, families and communities for years after release.

Some new data shines a light on these long-term psychological effects of incarceration. A new survey about literacy behind bars also included some important questions about individual experiences of social and political isolation. The literacy findings have few surprises; like earlier studies indicate, incarcerated people score lower on various measures of literacy. (The new U.S. Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies does add some new dimensions to our understanding of literacy in prisons, providing data on prison employment and educational programming.)

In the U.S. Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, participants were asked to respond on a five-point scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” with the following three statements:

- People like me don’t have any say about what the government does.

- There are only a few people you can trust completely.

- If you are not careful, other people will take advantage of you.

The findings of these three questions about social and political isolation reinforce the conclusions of prior research, suggesting that criminal justice involvement at any level impacts political engagement and trust. Compared to the data collected from U.S. households, the survey of U.S. prisons indicates higher levels of mistrust, political disenfranchisement, and political alienation among incarcerated adults.

The fact that incarcerated people feel more socially and politically isolated fits with previous research on how incarceration impacts the relationship people have with their government, beyond explicit political disenfranchisement. For example, a 2010 study found that people with justice system involvement “withdraw from political life,” evidenced by decreased participation in civic groups, decreased expression of political voice in elections, and diminished trust in government.

This issue has the capacity to affect entire communities. Research by Dr. Traci R. Burch finds that the criminal justice system shapes community political participation. She studied the ways in which political disenfranchisement restricting one individual impacts the political involvement of neighbors living around him or her in North Carolina. Dr. Burch found that people living in neighborhoods with more criminal justice-involved individuals (previously incarcerated and/or under community supervision) are less likely to vote, even if they are not disenfranchised themselves. Not only are they less likely to vote, but they are also less likely to engage in multiple forms of political participation, to be registered voters, and to participate in broader civic engagement. This means that contact with with the criminal justice system impacts not only individual experiences of political participation, but also community-wide political engagement.

With this study, we are reminded again that the harms of incarceration ripple outward from individuals throughout communities. Incarceration has a deadening effect on the political engagement of incarcerated people, and also on their families, friends, and neighbors. At this critical time, when political participation is at fever pitch, it’s important to recognize that mass incarceration undermines the political participation of entire communities.