At a time when phone calls for the rest of us cost almost nothing, there is no reason to force the poorest families in Iowa to pay outlandish rates.

April 26, 2019

For immediate release — The Prison Policy Initiative has filed objections to five phone companies’ proposed phone rates for Iowa county jails. At a time when the cost of a typical phone call is approaching zero, phone providers in Iowa jails frequently charge incarcerated people and their families 30 cents per minute or more for a phone call. (And one provider charges as much as $4.41 for the first minute.)

In January, the Iowa Utilities Board required these providers to file rate disclosures – or “tariffs” – for state approval. By state statute, the Utilities Board must ensure that rates are just and reasonable and that “no unreasonable profit is made.” The Prison Policy Initiative’s research has found that phone calls from Iowa’s jails are among the most expensive in the nation, and more than four times as expensive as calls from the state’s prison system.

In February, the Prison Policy Initiative report State of Phone Justice uncovered the cost of phone calls in over 2,000 jails nationwide, explaining why sheriffs sign lucrative phone contracts that prey on people in jail and their families:

- Phone providers compete for jail contracts by offering sheriffs large portions of the revenue – and then charge exorbitant phone rates.

- Providers exploit sheriffs’ lack of experience with telecommunications contracts to slip in hidden fees that fleece consumers.

- State legislators, regulators and governors traditionally pay little attention to jails, even as they continue to lower the cost of calls home from state prisons.

The report found that calls home from Iowa jails are the 13th most expensive in the nation. “There is no reason to force the poorest families in Iowa to pay these outlandish rates, particularly at a time when phone calls for the rest of us cost almost nothing,” said Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative.

The objections were filed with the research assistance of volunteer attorney Stephen Raher, and the organization is now being represented pro bono before the Iowa Utilities Board by David Yoshimura of Faegre Baker Daniels in Des Moines.

The Prison Policy Initiative’s objections to the tariffs are available for: Global Tel*Link, Public Communications Services, Prodigy Solutions, Reliance Telephone of Grand Forks, and Securus.

Yesterday, the Iowa Utilities board granted our request to intervene and docketed the tariffs for further review. Further comments about the proposed tariffs are due May 13.

People on probation are much more likely to be low-income than those who aren't, and steep monthly probation fees put them at risk of being jailed when they can't pay.

by Mack Finkel,

April 9, 2019

Over 3.6 million people are under probation supervision in the U.S., and in most states, they are charged a monthly probation fee. The problem? Many of them are among the nation’s poorest, and they can’t afford these fees. From our previous research in Massachusetts – and from reports from around the country – we know that the burden of probation fees often falls disproportionately on the poor. To determine the extent of the problem nationally, we examined the incomes of people on probation in a recent survey, the National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Our analysis confirms that, nationwide, people on probation are much more likely than people not on probation to have low incomes.

The National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) is an annual survey that asks respondents about a broad range of topics, including their annual income and whether they were on probation in the past 12 months. The inclusion of recent probation history in the survey makes it a valuable data source for criminal justice research; it comes closer than any other source to offering a recent, descriptive, nationally representative picture of the population on probation.1 Prof. Michelle Phelps of the University of Minnesota, for example, used this survey in her recent analysis comparing people on probation to those in prison, using educational attainment as a measure of economic status.

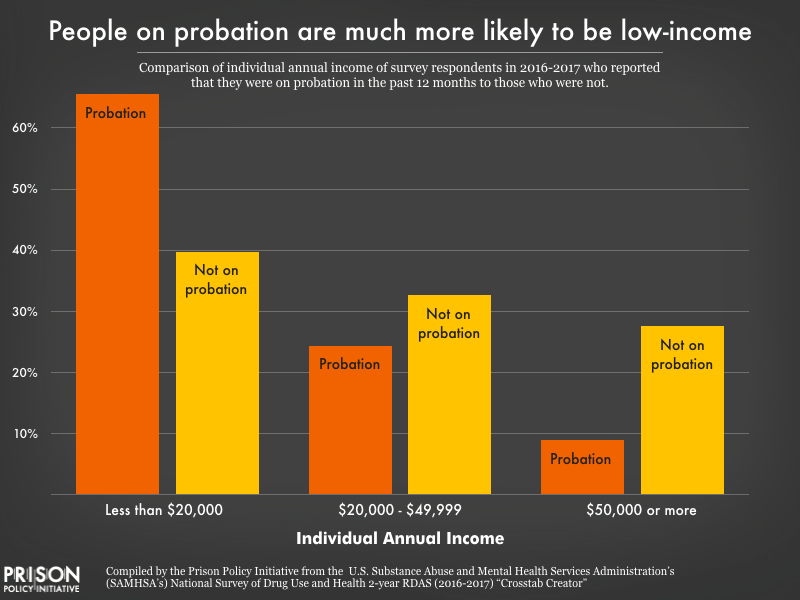

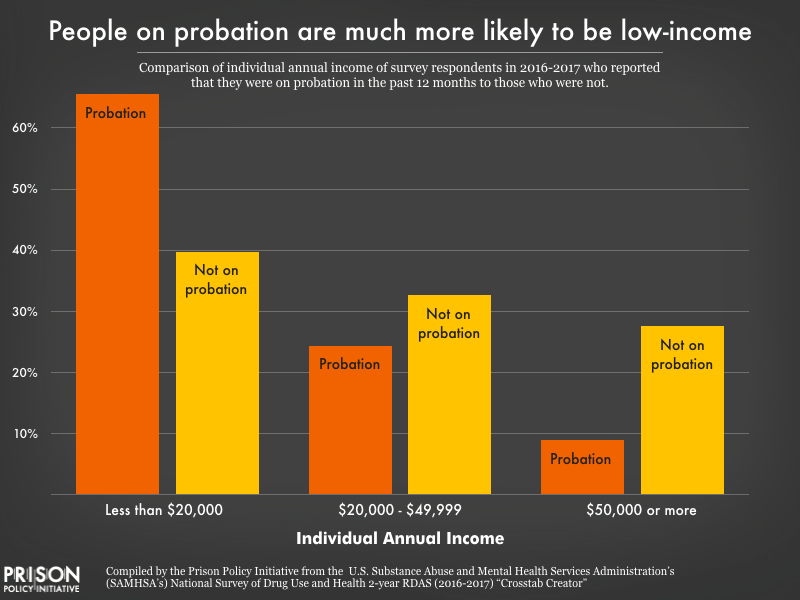

Our analysis of the 2016-2017 NSDUH data shows that people on probation typically have much lower incomes than those who aren’t on probation:

People on probation are much more likely to be low-income than those who aren’t on probation, and steep monthly probation fees often put them at risk of being jailed when they can’t pay. For a more detailed comparison, see the Appendix table.

People on probation are much more likely to be low-income than those who aren’t on probation, and steep monthly probation fees often put them at risk of being jailed when they can’t pay. For a more detailed comparison, see the Appendix table.

Key findings from our analysis include:

- Nationwide, two-thirds (66%) of people on probation make less than $20,000 per year.

- Nearly 2 in 5 people on probation (38%) make less than $10,000 per year, well below the poverty line.

- On the wealthier end of the spectrum, few people (9%) on probation have annual incomes of $50,000 or more, while more than a quarter (28%) of those not on probation make at least $50,000 per year.

Monthly probation fees may be just one of several fees that someone on probation has to pay regularly. As part of the conditions of their probation, an individual might have to pay court costs, one-time fees, monthly supervision fees, electronic monitoring costs, or any combination of these charges. Sometimes the law strictly defines the cost of these fees, and sometimes “reasonableness” is the only statutory guideline. Depending on the state, courts, departments of corrections, sheriffs’ departments, and the probation programs themselves can all collect revenue from these fees.

Even though the Supreme Court has said it is unconstitutional to incarcerate someone because they cannot afford to pay court ordered fines and fees, many courts effectively do just that. Judges often fail to consider the individual’s ability to pay (as opposed to their willingness to pay) and treat nonpayment of fees as a violation of probation. This flies in the face of many state statutes that allow incarceration only when there is evidence that the individual is able to pay but refuses.2 As a result, poor people on probation face a very real risk of being incarcerated because they can’t afford monthly fees. As the National Criminal Justice Debt Initiative shows, many state laws amount to “poverty penalties” and “poverty traps” and failure to pay can mean an extended probation sentence, driver’s license revocation, mandatory work program, or incarceration.

*In Massachusetts, the fees have two tiers, $50 for administrative and $65 for supervised probation. In Oklahoma, there are two separate monthly supervision fees, one up to $40 and another up to $20.

**Due to the small number of NSDUH respondents in Maine and South Carolina who were on probation at any time in the past 12 months, the survey does not make the necessary data available for those states as part of NSDUH’s efforts to protect respondents’ identities.

This table includes states where probation fees can cost $50 or more each month, and shows that in almost all of these states, over half (and even as many as 83%) of people on probation have annual incomes below $20,000. For them, unaffordable probation fees can lead to a cycle of poverty and incarceration. (Sources: Criminal Justice Debt Reform Builder, for probation fees, and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2-Year RDAS (2016-2017) for income data on the population experiencing probation in the past 12 months.)

| State |

Monthly supervision fee |

Portion of probation population

making less than $20,000 per year |

| Colorado |

Up to $50 |

48% |

| Idaho |

Up to $75 |

67% |

| Illinois |

$50 |

65% |

| Louisiana |

$71 to $121 |

69% |

| Maine |

$10 to $50 |

NA** |

| Massachusetts |

$50 or $65* |

52% |

| Michigan |

Up to $135 |

67% |

| Mississippi |

$55 |

67% |

| Montana |

At least $50 |

64% |

| New Mexico |

$15 to $150 |

83% |

| North Dakota |

$55 |

77% |

| Ohio |

Up to $50 |

62% |

| Oklahoma |

Up to $60* |

75% |

| South Carolina |

$20 to $120 |

NA** |

| Washington |

Up to 100 |

50% |

Such high fees – and high stakes – defeat the purpose of probation. In theory, probation (often touted as an “alternative” to incarceration) allows people to continue to work and manage family responsibilities while under supervision. But people faced with unaffordable fees are more likely to violate the conditions of supervision, experience housing and food instability, and struggle to support their children. And when failure to pay is treated as a violation of probation, individuals can be incarcerated, have their probation extended, and/or lose public benefits like food stamps and supplemental security income.

Louisiana is an especially punishing state for poor people on probation. The average probation sentence there lasts three years, and probation fees are among the highest in the country, at $71 to $121 per month, even though 69% of people on probation make less than $20,000 per year. Data from a report by the state’s Justice Reinvestment Task Force shows just how unreasonable these fees are. In Louisiana in 2015:

- While under community supervision, the average person owed $1,740 in supervision fees alone. (Supervision fees were just one type of a number of court-ordered fines and fees.)

- On average, people under supervision could only pay about half of the imposed fees; at the end of their supervision term, the average person still owed 48% of their supervision fees.

Louisiana’s probation system creates impossible debts that unfairly burden poor probationers. As in many states, failure to pay can lead to license suspensions, extension of supervision terms, and incarceration.

Fortunately, this is slated to change. Under a new law going into effect in August 2019, Louisiana courts will hold hearings on ability to pay, and defendants may have their fees waived or reduced if the court finds that fees will cause substantial financial hardship. While the fees are still far too high, the new law offers hope for low-income people on probation. (It’s worth noting that judges, district attorneys, and court clerks whose offices benefit from the fees have fought to delay the implementation of the law.)

As long as probation sentences include unreasonable fees and harsh punishments for failure to pay them, probation will continue to punish people just for being poor. Some states have begun to implement reforms to reduce the unnecessary incarceration and other unintended consequences of their probation fee systems. But as our analysis shows, this is a widespread problem that every state imposing probation fees should address. States must acknowledge that people on probation are mostly low-income, and driving them further into poverty through monthly fees is cruel and counterproductive.

Appendix table: Percentage of Probation Population vs. Non-Probation Population in Each Category of Personal Annual Income (Source: NSDUH 2016-2017)

| Personal Annual Income |

Less than $10,000 |

$10,000 to $19,999 |

$20,000 to $29,999 |

$30,000 to $39,000 |

$40,000 to $49,999 |

$50,000 to $74,999 |

$75,000 or more |

| On probation in the past 12 months |

37.9% |

27.7% |

13.4% |

7% |

5% |

6.1% |

2.9% |

| Not on probation in the past 12 months |

21.8% |

17.9% |

13% |

10.7% |

9% |

12.3% |

15.3% |

A merger between the two companies would have curtailed the ability of prisons and jails to choose a phone provider, to the detriment of incarcerated people and their families.

April 2, 2019

Easthampton, Mass. – Prison phone industry giant Securus has abandoned its attempt to purchase ICSolutions, the industry’s third largest company, after the Federal Communications Commission and the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division signaled that they would likely block the deal. The merger would have effectively handed the market for prison and jail phone services over to Securus and its last major competitor, GTL.

“Based on a record of nearly 1 million documents comprised of 7.7 million pages of information submitted by the applicants, as well as arguments and evidence submitted by criminal justice advocates, consumer groups, and other commenters, FCC staff concluded that this deal posed significant competitive concerns and would not be in the public interest,” said FCC chairman Ajit Pai in a press release.

“Securus and ICS [Inmate Calling Solutions] have a history of competing aggressively to win state and local contracts by offering better financial terms, lower calling rates, and more innovative technology and services. This merger would have eliminated that competition, plain and simple,” said Makan Delrahim, Assistant Attorney General of the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division in a press release. “The companies’ decision to abandon this deal is the right outcome – correctional facilities, inmates and their friends and families will continue to benefit from the robust competition between these firms.”

“All too often, calls home from jails cost an unconscionable $1/minute,” said Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative. “Had the companies merged, facilities would have had a harder time negotiating contracts with lower rates for families – which, thanks to our movement’s ongoing advocacy, they’re finally beginning to do.”

In our objection to the merger, filed in July 2018 with a coalition of groups working for prison phone justice represented by probono attorneys Davina Sashkin and Cheng-yi Liu, we argued that the FCC should stop the merger.

We argued that Securus’ history of repeatedly flouting commission rules – including deliberately misleading the FCC during a similar review last year, for which it was punished with an unprecedented $1.7 million fine – made it ineligible to purchase one of its competitors. We explained that the company has repeatedly tried to circumvent regulation in order to increase its profits from prison phone calls, and as recently as May 2018 was caught enabling illegal cell phone tracking.

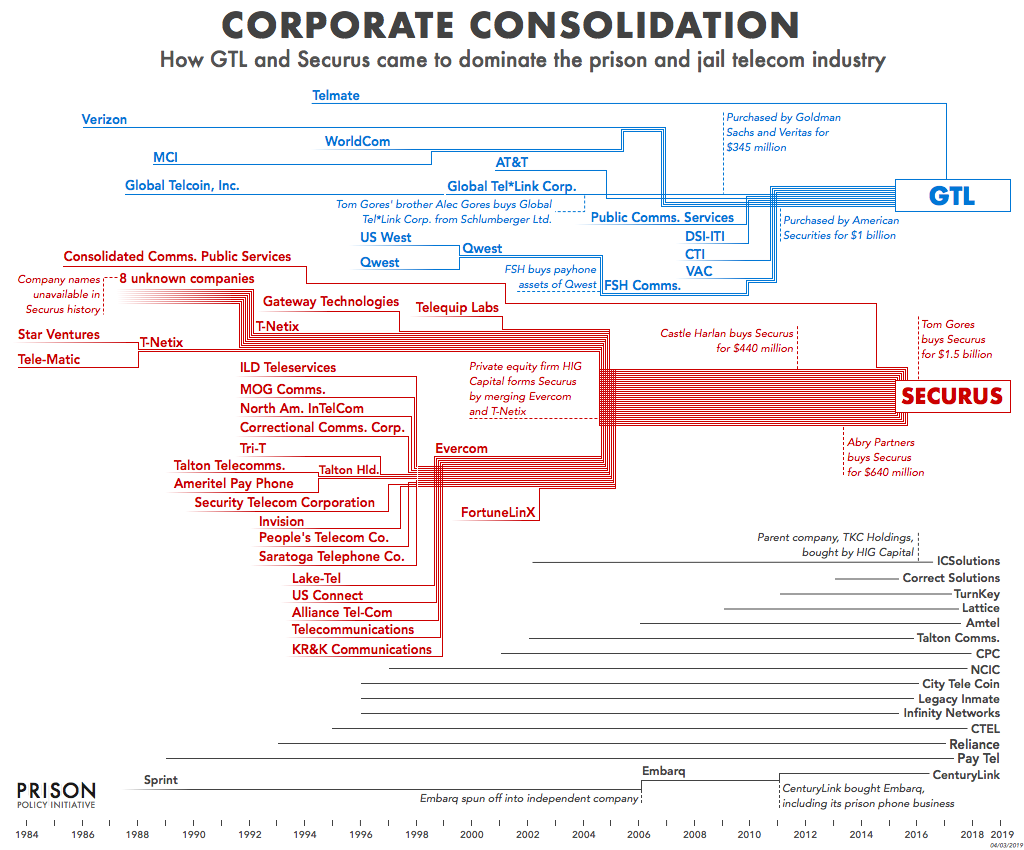

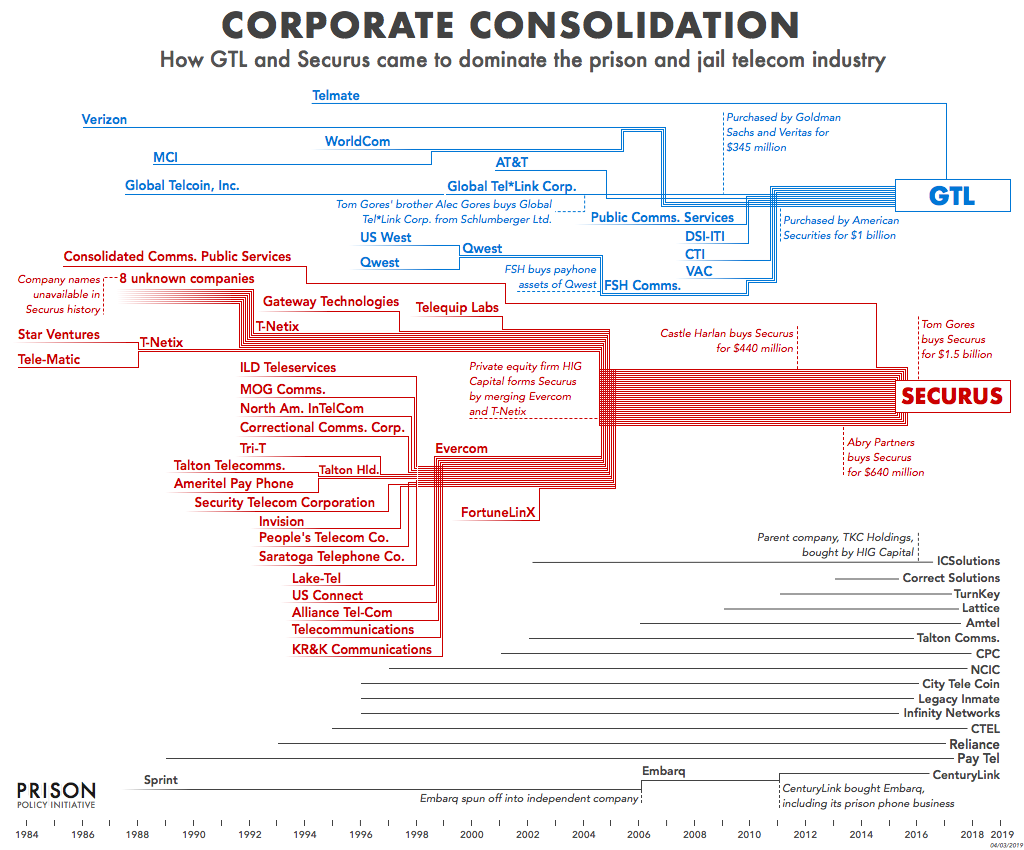

Our filing included a detailed analysis of the concentration of the prison and jail telephone industry. We calculated market share in two different ways; by either measure, Securus and GTL were poised to control between 74% and 83% of the market. Except for ICSolutions – which Securus was seeking to acquire – no other company had above 3% market share.

Below is a historical timeline originally prepared for our report State of Phone Justice: Local jails, state prisons and private phone providers, showing how aggressively Securus and GTL have been gobbling up their competitors:

For more information about this timeline, the companies, their respective sizes, the role of companies like CenturyLink that operate only in partnership with Securus and ICSolutions, or the historical role of AT&T and Verizon, see our report, the footnotes, and appendices to State of Phone Justice: Local jails, state prisons and private phone providers.

Updated April 3, 2019 10am with FCC press release and 1pm with the Department of Justice’s press release.

People on probation are much more likely to be low-income than those who aren’t on probation, and steep monthly probation fees often put them at risk of being jailed when they can’t pay. For a more detailed comparison, see the

People on probation are much more likely to be low-income than those who aren’t on probation, and steep monthly probation fees often put them at risk of being jailed when they can’t pay. For a more detailed comparison, see the