Force multipliers: How the criminal legal and child welfare systems cooperate to punish families

Child protective service agencies position themselves as providers of welfare, but their relationship to the criminal legal system demonstrates their shared role in punishing families and exacerbating the conditions that lead to system involvement in the first place.

by Emma Ruth, January 8, 2024

The harmful effects of the criminal legal system on children are well-established. For years, evidence has shown that a parent’s involvement with the criminal legal system can harm kids, and incarcerating children has lifelong consequences. We’ve reported on efforts in several states to mitigate the negative impact of the criminal legal system on children but seldom discussed how the criminal legal and child welfare systems are deeply interwoven. A growing number of advocates and experts are bringing these connections to light and are organizing for momentous change. This briefing draws attention to their work to argue that, by expanding our view beyond jails and prisons to include these related systems, advocates and policymakers can safeguard against creating prisons by another name.

By the numbers: involvement in each system

Presently, the child welfare system surveils millions of families each year, many of whom are also impacted by the criminal legal system. Though data about the overlap between the two systems are faulty and likely underreported,1 data about strictly parental incarceration or child protective services2 involvement are more accessible. In our August 2022 briefing, Both sides of the bars: How mass incarceration punishes families, we explained the magnitude of the criminal legal system’s impact on children and families, noting that nearly half of people in prison are parents to minors and that 1.25 million children are impacted by parental imprisonment on any given day.3

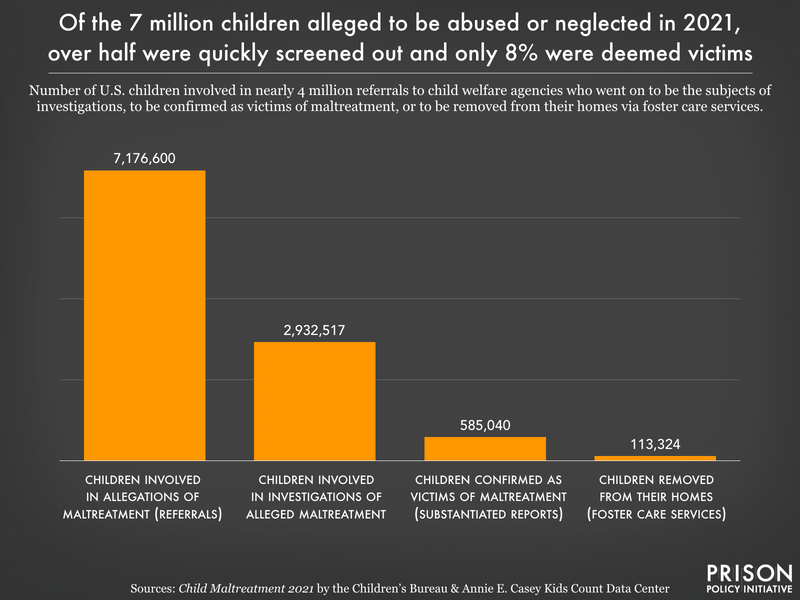

Annual government reports illustrate the size and scope of child protective services. In 2021, nearly 4 million calls were made to those agencies, alleging that around 7.2 million children were being neglected or abused. Each year, approximately half of these calls are immediately determined to be illegitimate, lack enough information, or otherwise fail to meet the criteria for a child maltreatment report. In other words, rampant overreporting is the norm. Even when such reports are screened out, mere contact with the child welfare system can have damaging effects on families that last for decades, much like collateral consequences from brushes with the criminal legal system.

The consequences of dual-system involvement

Child welfare investigations bring parents and children in closer contact with the criminal legal system, increasing the likelihood of dual-system involvement. A 2010 study noted that there are four likely pathways to a family becoming involved with the child welfare and criminal legal systems simultaneously:

- A parent’s arrest coincides with child welfare system involvement, such as an arrest leading to a maltreatment report;

- A parent’s record is determined to compromise their child’s safety;

- Relatives who might ordinarily be considered for next-of-kin placement (placement of a child in the temporary or long-term custody of a non-parent relative) are determined ineligible due to their record;

- A child enters foster care because of issues with the temporary guardian they are staying with while their parent is incarcerated.

The limited data on dual-system involvement show that parental incarceration was listed as the reason for entry for 6% of children who entered foster care in 2022.4 Estimates range, but one 2017 study estimated that 40% of children who have been in foster care have also had a parent incarcerated in their lifetime. Parental incarceration is just one pathway to criminal legal system involvement: over half of youth in foster care will have an encounter with the juvenile legal system by age 17, a phenomenon that some have dubbed the foster care-to-prison pipeline.

Beyond quantitative data, several recent publications expose the connective tissue between the criminal legal and child welfare systems. In her recent piece for In These Times, Roxana Asgarian writes:

Critics say [the child welfare system] is more akin to law enforcement than social services, given its ability to surveil parents and hand down the ultimate punishment — terminating the legal bonds between parent and child.

In recognition of these similarities, advocates for child welfare system reform and abolition have taken to calling it the “family regulation” or “family policing” system, arguing that it, too, primarily functions to surveil, regulate, and punish disproportionately Black and Brown families.

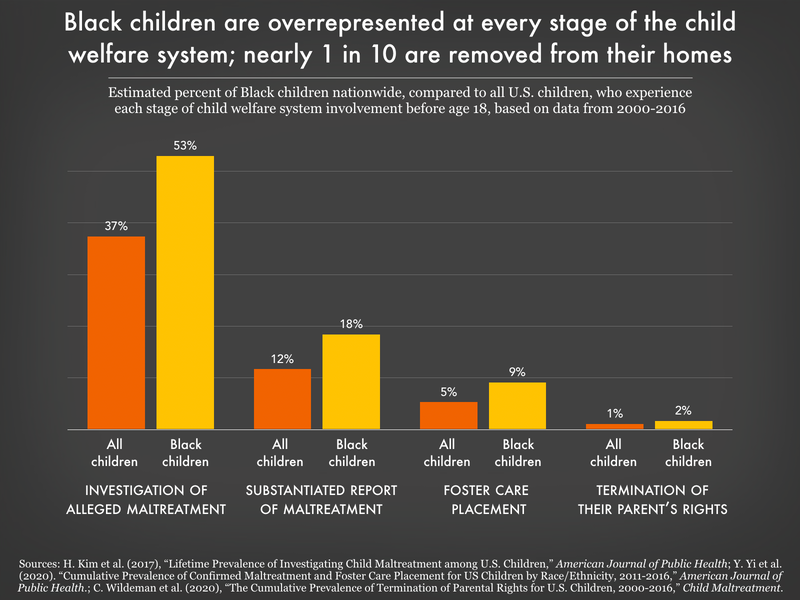

Just as Black and Brown people are overrepresented in jails and prisons, their families are overrepresented at every stage of a child protective services case. Black and Indigenous parents, in particular, are over-reported and over-investigated and are more likely to have their children removed and their parental rights terminated. Black and Brown youth are also overrepresented in the foster system: In California, for example, Black children are represented in foster care at a rate of 3.7 times their proportion in the population.5 Further, Black and Indigenous children enter foster care at roughly double the rate of white children nationally. These systems not only target the same communities, but the same individuals: incarcerated people are more likely to have been in foster care previously than others, and youth in foster care are more likely to become incarcerated as adults. Involvement in one system makes families vulnerable to becoming involved with the other.

Dual punishment: Incarceration and termination of parental rights

We have previously reported on the harm of family separation by incarceration, which is amplified by the threat of permanent termination of parental rights that can follow. Impossible-to-follow service plans and legislative loopholes make it so that 1 in 8 incarcerated parents who have a child in foster care will lose their parental rights entirely.

Service plans — the behavioral modification programs that child protective services can impose on families who are involved in an active case — often require that parents attend mandated classes, see specific counselors, engage in supervised visits, and take other steps to regain their custody, all of which is nearly impossible when a parent is incarcerated. But prisons and jails are not required to accommodate the service plans that parents must follow in order to regain custody, and child welfare agencies are not required to accept available prison programming as “reasonable progress” towards reunification. Meanwhile, the clock is ticking: federal legislation mandates that states must move to terminate a parent’s rights when a child is out of their parent’s custody for 15 out of 22 consecutive months during a child welfare case, even if that separation is due to a parent’s incarceration.6

According to a 2023 study called The Relationship Between Black Maternal Incarceration and Foster Care Placement, “Parental incarceration can also qualify as an ‘aggravated circumstance,’ relieving child welfare agencies from the [statutory requirement] to make ‘reasonable efforts’ to reunify families or limiting the number of months in which ‘reasonable efforts’ must be made.” These systems intensify the impacts of each other in a feedback loop, causing parents and their children to experience multiple forms of punishment, often for the same offenses.

The same problems pervade both systems

In the absence of flourishing social safety nets, both the criminal legal and child welfare systems have become catch-all nets to address social issues that they’re not equipped to deal with. Just as many adults who are experiencing intimate partner violence call the police not to report a crime, but because they need crisis management, child welfare reports are often used to mediate interpersonal conflict. Reports of people weaponizing child welfare reports during disputes, or making retaliatory reports to gain leverage during custody battles, are common.

Both systems respond to substance use or mental health challenges with punishment, not treatment. Much like treatment mandates handed down by drug courts ignore research indicating treatment is less effective when it’s coerced,7 the same ineffective requirements are imposed on parents in child welfare cases. These requirements often feel more like punishment than help, and they fail to give parents real agency or choice. If the alternative to accepting treatment is becoming incarcerated or losing custody of your child, who is in a position to refuse? Child welfare agencies don’t make treatment affordable or accessible, failing to consider a parent’s schedule, life responsibilities, and transportation options. Further, parents are frequently required to pay for their mandated treatment, even though financial insecurity often leads to their involvement with the system in the first place.

State registries, much like those in the criminal legal system, have become commonplace, too. However, the threshold for appearing on a child welfare registry in many states is even lower: state central registers document substantiated and unsubstantiated allegations, not just findings of guilt. As is the case with an arrest or conviction record, or being listed on the sex offense registry, inclusion in the state central register can create future obstacles to accessing employment and child custody. In this way, both systems operate as agents of surveillance, not justice.

The interplay between these two systems is increasingly alarming. States that spend more on carceral practices have higher rates of child removal than states that spend more on social welfare. Federal grants for universities incentivize social work schools to partner with child welfare agencies, developing pipelines that push social workers into collaborating with them. Many jurisdictions are developing more partnerships between police and social workers, which are often lauded as progressive reforms. This has led many in the social work field to question whether their role is to punish people. Criminal legal system and social work advocates must ask, can we address issues in the criminal legal system by investing in another system that’s riddled with the same problems?

How advocates are addressing the problem

Over three-quarters of child welfare cases in 2021 alleged neglect, a vaguely-defined term that is often used to blame to parents for having insufficient resources to care for their children.8 Rather than using the child welfare and criminal legal systems to punish parents who are facing resource scarcity, advocates are tackling the resource gaps that led families to become system-involved in the first place by providing direct cash assistance. Family policing abolitionists want to confront child abuse while providing solutions that resource parents and communities and keep them united with their children. They question the true function of the family regulation system and point to how it worsens many of the issues seen in the criminal legal system.

In the last several years, a number of groups have emerged to formalize Black mothers’ longstanding efforts to resist state interventions and family separation and repeal the Adoption and Safe Families Act. These and other coalitions of advocates have been working towards expanding representation for impacted parents and attempting to create Miranda Rights for those under investigation by New York’s Administration for Children’s Services. In 2019, New York passed legislation to limit the scope of its state central register by raising standards of evidence for being placed upon it, creating new and shorter pathways to sealing a record, and options to mitigate its effects on employment.

A steadily increasing number of advocates and social service providers are developing tools to expand the practice of mandatory supporting, instead of mandatory reporting,9 by prioritizing resourcing families over making child welfare reports. In 2021, New York advocates introduced legislation to make reports confidential instead of anonymous to increase accountability and minimize malicious reporting. In 2023, New York City parents rallied to support legislation to repeal mandatory reporting altogether. Meanwhile, legislation introduced in Colorado that same year would require the courts to make it feasible for incarcerated parents to adhere to the requirements of their ongoing neglect case or service plan.

Universal basic income pilots for formerly incarcerated people, such as those in Chicago and Durham, show promise at improving post-release outcomes and decreasing recidivism rates.10 Financial assistance for families reduces rates of child maltreatment, and California is exploring how basic income programs can improve outcomes for young adults leaving foster care.

Breaking the cycle: applying lessons from both systems

Dispelling the myth that most harm against children is caused by “criminally-minded” individuals whom courts can pathologize and punish away requires addressing the material causes of child maltreatment. In the 70% of child welfare cases that are strictly for neglect, that means addressing poverty. In every case, that means contending with the barriers that prevent people from obtaining quality mental and physical healthcare and the structures that bar parents from getting the support they need to be their best selves for their kids. If child maltreatment is a structural issue rooted in poverty and interpersonal violence, then structural solutions are necessary to alleviate both.

The child welfare and criminal legal systems are failing to provide families with the safety and transformative resources that they need. Both systems surveil, regulate, and punish people, and do nothing to transform their conditions. Both are fraught with racist and bureaucratic structures that formalize the repression of Black and Brown families. And neighborhoods that have frequent contact with child protective services and police often suffer from fraught and less trusting community relationships, pushing them further from, not closer to, true public safety.

Because they are so intertwined, each system’s damaging impacts can and should be remedied concurrently: advocates are fighting to better resource families before they ever come in contact with them; they are shrinking their footprint in schools, healthcare, and other public services that surveil them; and they are ensuring better representation for families who are already ensnared. Policymakers must look to these advocates as leaders and respond to their calls for more resources and less punishment.

Criminal legal system reformers’ work can be strengthened through solidarity with people who are fighting family policing and regulation. They provide prescient guidance about the pitfalls of investing in supposed “helping” alternatives to incarceration that produce more mandated programs, surveillance, and criminal legal system involvement. Their work inspires advocates to think more critically about the true meaning of community safety and invites us all to expand our focus from “fixing prisons and jails” to ending the systems of oppression that built jails, prisons, and their welfare system counterparts in the first place.

Footnotes

-

Caseworkers often only record one reason for entry, so parental incarceration may not be listed as the reason for removal even if it was a factor in the case. ↩

-

We are using “child protective services” and “child welfare agencies” to refer to state agencies that respond to alleged acts of child abuse and neglect. However, we should note that these agencies often go by a variety of names in different states; for example, Wyoming’s agency is called the Department of Family Services, and in Ohio, it’s called the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services. ↩

-

On a given day, an estimated 1.25 million minor children have a parent incarcerated in a state prison. This estimate excludes those with parents in federal prisons and locally-operated jails, and overlooks the ongoing impacts of prior parental incarceration and collateral consequences from past arrests or convictions. ↩

-

This data covers Federal Fiscal Year 2021, which ranges from October 1, 2021 to September 30, 2022. ↩

-

Black, multiracial, and Indigenous (i.e., American Indian or Alaska Native) youth are overrepresented nationally, compared to their shares of the total youth population. White, Asian, and Latino (or Hispanic) youth are underrepresented nationally, though Latino (or Hispanic) youth are overrepresented in some states. By using this Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System Data Dashboard, you can change the “Data Display” to look at different rates of disproportionality by area and race. ↩

-

Six states prohibit filing for termination of parental rights solely due to incarceration.

↩ -

The literature is mixed but largely inconclusive as to whether compulsory treatment for substance use disorder is effective. A large meta-analysis from 2008 revealed that voluntary treatment, as compared to mandatory or coerced treatment, produced the largest treatment effect (non-recidivism) in participants. Meanwhile, the advocacy group Physicians for Human Rights has pointed out that mandatory treatment can be ordered for people for whom it’s not appropriate, and take opportunities away from people who are seeking it voluntarily. ↩

-

According to an analysis of statutory definitions of child neglect that looked at laws in all 50 states, “in many cases, neglect definitions contain vague or subjective descriptions of parental acts or omissions and do not require evidence of serious harm or imminent risk of serious harm.” Often, these subjective descriptions are suggestive of scarcity more than anything else: In New Jersey, for example, this includes “failure to provide ‘clean and proper home.'” ↩

-

The concept of “mandatory supporting” is an idea that was initially conceptualized by Joyce McMillan of JMAC for Families. ↩

-

Recividism is a loaded and misleading term that often equates technical parole violations with getting charged with new crimes. For a more nuanced discussion of this term, see our recidivism explainer in Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie. ↩

Appendix

Cumulative prevalence of child welfare system contact before age 18 by race or ethnicity

| All U.S. children | American Indian or Alaska Native children | Asian or Pacific Islander children | Black children | Hispanic or Latino children | White children | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investigation of alleged maltreatment before age 18 | 37.4% | 23.4% | 10.2% | 53.0% | 32.0% | 28.2% | H. Kim et al. (2017), “Lifetime Prevalence of Investigating Child Maltreatment among U.S. Children,” American Journal of Public Health |

| Substantiated report of maltreatment before age 18 | 11.7% | 15.8% | 3.5% | 18.4% | 11.0% | 10.5% | Y. Yi et al. (2020). “Cumulative Prevalence of Confirmed Maltreatment and Foster Care Placement for US Children by Race/Ethnicity, 2011-2016,” American Journal of Public Health |

| Out of home placement before age 18 | 5.3% | 11.4% | 1.5% | 9.1% | 3.8% | 5.0% | Y. Yi et al. (2020). “Cumulative Prevalence of Confirmed Maltreatment and Foster Care Placement for US Children by Race/Ethnicity, 2011-2016,” American Journal of Public Health |

| Termination of parent’s rights before age 18 | 1.1% | 2.7% | 0.2% | 1.7% | 0.9% | 1.0% | C. Wildeman et al. (2020), “The Cumulative Prevalence of Termination of Parental Rights for U.S. Children, 2000-2016,” Child Maltreatment |

I am 76 yoa and recently retired attorney who has recently run for Caddo Parish DA (in 2022) and Caddo Parish Sheriff (in 2023). While unsuccessful in my campaigns, thousands of folks did vote for me. I opened the doors and windows of the fraud and corruption that is rampant in this parish. I vehemently voted “NO” for a tax increase for the “Juvenile Justice Center” in our parish and said it should be shut down completely until someone figures out how to run it properly. It does as much harm as it does good.

Keep up the good work you are doing back in my home state of Illinois.

What can I do to help myself with this situation as a family

Nora, I’m so sorry to hear about what your family is going through. We can’t offer legal advice, but we keep a list of organizations that offer legal assistance to incarcerated people in civil matters, and some of these organizations may work on family/custody issues as well as criminal legal issues: https://prisonpolicy.org/resources/legal

I also suggest contacting upEND, whose work is focused on the child welfare system. They might have suggestions for you. Here’s their contact page: https://upendmovement.org/contact/

Best of luck. I’m sorry we can’t do more.