Explaining Texas’ overnight prison boom

By drastically slowing releases from prisons, Texas policymakers ensured that the state’s prison population would more than double in only five years in the 1990s. Decades later, Texans are still dealing with the consequences.

by Rachel Gandy, August 7, 2015

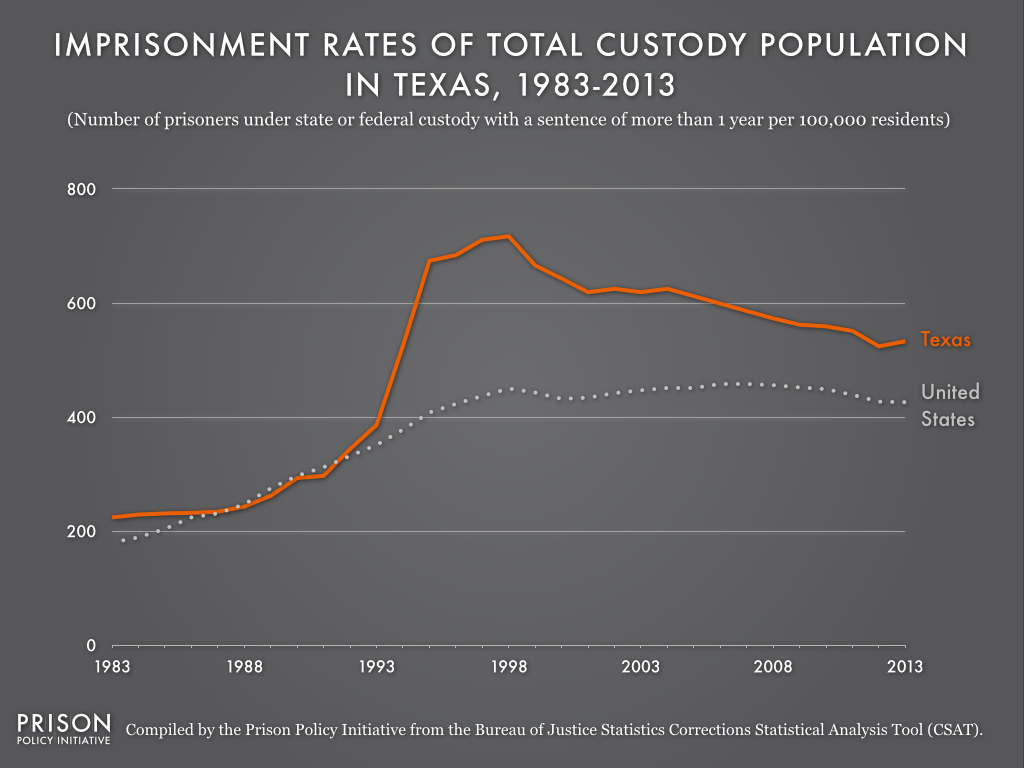

In May 2014, the Prison Policy Initiative created incarceration profiles for each state, and the Texas statistics were shocking. They revealed a doubling of the Texas prison population in just a few years. As a native Texan, high imprisonment rates were no surprise, but the rapid rise in imprisonment seemed almost impossible, especially compared to the nation as a whole:

Throughout the 1980s, the Texas imprisonment rate closely matched the national imprisonment rate. But between 1993 and 1998, the Texas imprisonment rate almost doubled, causing Texas’ total custody population to quickly escalate.

Throughout the 1980s, the Texas imprisonment rate closely matched the national imprisonment rate. But between 1993 and 1998, the Texas imprisonment rate almost doubled, causing Texas’ total custody population to quickly escalate.

The imprisonment rate in Texas has been generally equal to or higher than the national imprisonment rate. This fact was no surprise because Texas has been known for its tough-on-crime mentality. But what was so special about 1993 that caused the imprisonment rate in Texas to skyrocket?

The answer lies in the underlying mechanisms that drive prison admissions and releases. As Michele Deitch, a Soros Senior Justice Fellow and Texas criminal justice expert, describes, correctional facilities are like bathtubs: people are admitted to prisons like water from the faucet and released like water from the drain. If admissions and releases are not in balance, prisons, like bathtubs, will overflow.

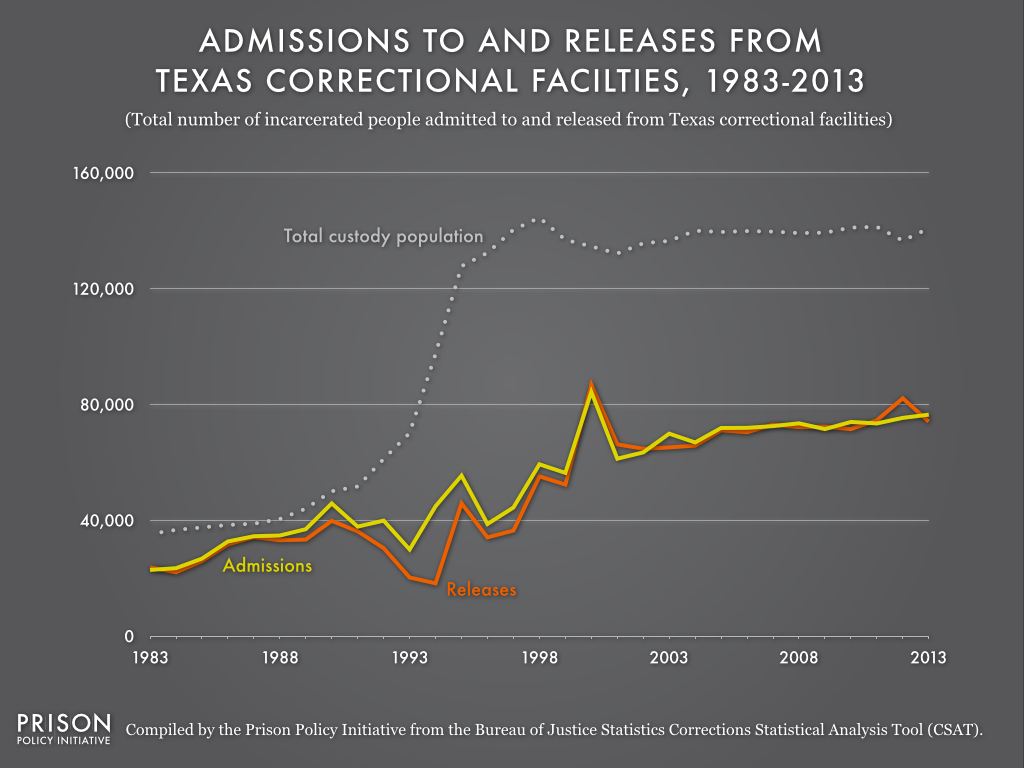

To test that analogy and uncover the policy change that sent Texas’ imprisonment rate soaring, I collected annual data on admissions to and releases from Texas prisons and graphed them both against the total custody population:

Beginning in 1993, the number of releases from Texas prisons fell behind the number of admissions, allowing the state’s total custody population to rise sharply for the next five years. Once release counts rose again to match admission counts, Texas’ total custody population leveled off and remained stagnant. These patterns show that admissions to and releases from prisons serve as at least one driving force behind rapidly changing prison populations.

Beginning in 1993, the number of releases from Texas prisons fell behind the number of admissions, allowing the state’s total custody population to rise sharply for the next five years. Once release counts rose again to match admission counts, Texas’ total custody population leveled off and remained stagnant. These patterns show that admissions to and releases from prisons serve as at least one driving force behind rapidly changing prison populations.

When Texas made the choice to reduce the rate of prison releases, the state prison population more than doubled in five years, just like a running bathtub would if a stopper were placed over the drain. More recently, other policy changes have allowed the number of releases to match the number of admissions, causing the total custody population to flatten out after its massive increase.

Before 1993, admission and release counts in Texas were roughly equal, so the total prison population grew only slightly. Driven by the War on Drugs, prison admission rates increased steadily in the 1980s, but they were closely matched by prison release rates. For example, incarcerated Texans in the early 1990s only served an average of 13% of their assessed sentences behind bars as a way to decrease rising prison overcrowding concerns.(*)

But the graph above shows that this pattern changed in 1993. Suddenly, the gap between the number of admissions to and releases from Texas prisons expanded.

Texas legislators created this imbalance by implementing two separate policy choices that joined together to catapult a seemingly overnight boom in the prison population. First, faced with lawsuits from county officials over jail overcrowding, Texas legislators approved the building of over 100,000 new prison beds within less than five years. Second, in response to public outrage over short prison stays, lawmakers passed legislation to ensure that incarcerated people served a greater proportion of their sentences behind bars. For example, some violent offenders were suddenly required to serve at least 50% of their sentences before they were parole eligible, which effectively doubled the length of prison time for many Texans.(**)

Legislators disregarded the need for balance between admissions to and releases from prison, and the bathtub overflowed. Over two decades later, Texans are still trying to clean up that mess. Sentencing and parole reforms have attempted to decrease the costs of the prison boom, but to truly make an impact on the size of the incarcerated population, policymakers need to understand one thing: prisons are like bathtubs. If you simultaneously open the faucet and cover the drain, you will create a flood.

Suggested reading:

- Michele Deitch, “Giving Guidelines the Boot: The Texas Experience with Sentencing Reform,” Federal Sentencing Reporter 6, no. 3 (1993): 138-143.

- To see reform efforts underway in Texas, see the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition’s website at http://www.texascjc.org.

Notes:

(*) Michele Deitch, “Giving Guidelines the Boot: The Texas Experience with Sentencing Reform,” Federal Sentencing Reporter 6, no. 3 (1993): 138-143.

(**) Michele Deitch, “Giving Guidelines the Boot,” see footnote (*).