Links and other resources for attendees at the Iowa Justice Summit where I gave the keynote address on Friday.

by Peter Wagner,

August 31, 2015

On Friday, I gave the keynote address at the Iowa-Nebraska NAACP‘s third annual Iowa Summit on Justice & Disparities, which brought together leaders such as Governor Terry Branstad, state decision makers, law enforcement, and reform advocates to discuss some of the most pressing issues facing the criminal justice system in Iowa.

As a guide for attendees who want more information, I wanted to share some links to the published research I discussed and summaries of some of the unpublished work that I mentioned in my talk.

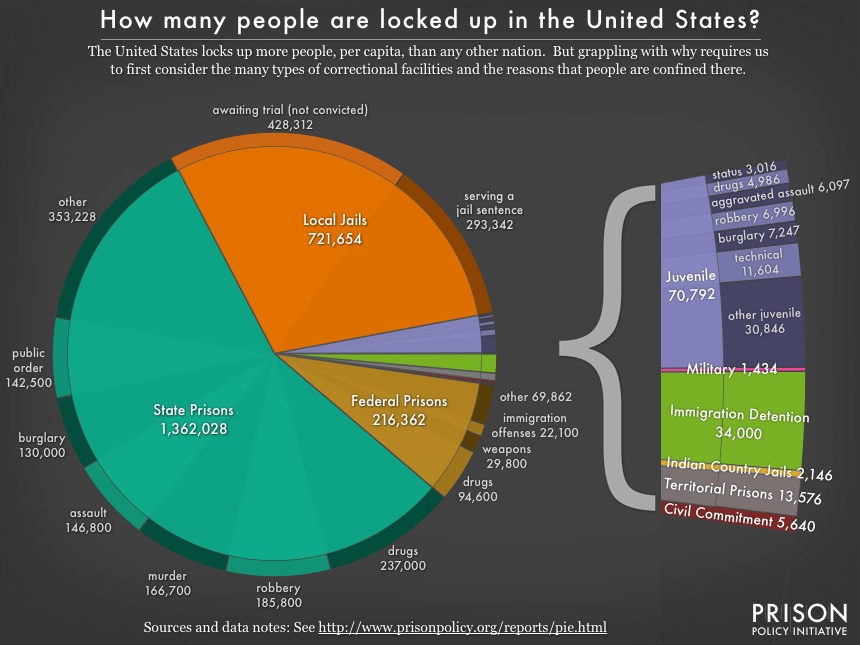

I addressed the globally unprecedented incarceration boom in the U.S. and Iowa:

I also addressed how even our economic, legal and cultural systems are built upon the assumption of mass incarceration to the detriment of people on both sides of prison walls:

During the Q&A, there were questions about:

And after my talk, I have had several conversations with participants about what the Prison Policy Initiative knows about the burgeoning video visitation industry that often bans in-person jail visits in favor of expensive computer chats nationwide and in Iowa. While more research in Iowa is needed, we know that these Iowa counties have adopted video visitation in some form:

- Buena Vista County

- Cerro Gordo County

- Des Moines County, which contracts with Lattice and charges $20 for a 40-minute visit

- Hardin County, which contracts with HomeWAV

- Iowa County

- Johnson County

- Polk County, which contracts with iWebVisit.com

- Pottawattamie County, which contracts with Securus

- Scott County

- Wapello County, which has replaced family in-person visits with video visits

- Woodbury County, which contracts with Securus

One exciting and immediate development from the Summit is that Governor Branstad has added telephone charges to his Working Group on Justice Policy Reform’s priorities.

If you are interested in bringing the Prison Policy Initiative to you, see our speakers page.

David Segal in the New York Times investigates whether companies that sell things to prisons feel threatened by the talk of prison reform.

by Peter Wagner,

August 31, 2015

A huge spread in the Business section of the Sunday New York Times focuses on reporter and columnist David Segal’s recent trip to the American Correctional Association conference, where he met companies of all sorts who sell prisons and jails the raw materials — except for people — needed for a prison or a jail. Segal, who also writes as The Haggler covering consumer protection issues and who previously blew the lid off the mugshot blackmail industry here grapples with the questions of policy change and what the companies who profit from the $80 billion spent on corrections each year are doing in response to all of the talk of prison reform:

A huge spread in the Business section of the Sunday New York Times focuses on reporter and columnist David Segal’s recent trip to the American Correctional Association conference, where he met companies of all sorts who sell prisons and jails the raw materials — except for people — needed for a prison or a jail. Segal, who also writes as The Haggler covering consumer protection issues and who previously blew the lid off the mugshot blackmail industry here grapples with the questions of policy change and what the companies who profit from the $80 billion spent on corrections each year are doing in response to all of the talk of prison reform:

For prison vendors, this would appear to be a historically awful moment. Sentencing reform has been gaining momentum as a growing number of diverse voices conclude that the tough-on-crime ethos that was born 40 years ago, and that led to a 700 percent increase in the prison population since 1970, went too far. Mandatory minimum laws, many of them passed at the state and federal level in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s locked people away for decades, often for relatively minor, nonviolent offenses. Those laws have had a disproportionate impact on African-Americans, who tend to serve longer sentences than whites.

But I’m quoted in a section that goes further to draw a line between all the reform that’s being talked about and what reform has actually looked like:

[The] vendors in Indianapolis seem unruffled by talk of prison reform. It hasn’t had a big impact, at least not yet, and it doesn’t seem that it will in the future.

To understand the “not yet” part, consider California, site of the country’s most ambitious inmate reductions. The court-ordered program to ease cramped, triple-bunk conditions started in October 2011. To date, the system’s head count in the 34 facilities covered by the overcrowding litigation has dropped to 111,000, from 144,000.

But the numbers aren’t quite what they seem. The law passed in 2011 mandated that new offenders sentenced for nonviolent or nonsex crimes would serve their time in county jails. The days when a jail was a just a pretrial holding pen are over, and the population in those cells is starting to bulge. Yes, there has been a net decline in the total population of incarcerated people in the state. Just not at a rate that would alarm anyone selling, say, inmate blankets.

“These declines are too small,” said Peter Wagner of the Prison Policy Initiative, which campaigns for prison reform. “The numbers are trending downward, but slowly and not consistently.”

Mr. Wagner also doubted that prison reform laws knocking around Congress, as well as many states, would reduce the prison population as much as some people thought, because they are focused on drug and nonviolent offenders. As numbers collected by the Urban Institute demonstrate, half of all inmates in state prisons are violent offenders, and state prisons are home to 86 percent of the nation’s inmates.

Segal addresses another reason why some of these companies aren’t bothered by talk of prison reform: there are plenty of ways to profit if governments merely transfer their prison addictions to other unnecessary forms of social control. Segal reports:

Segal addresses another reason why some of these companies aren’t bothered by talk of prison reform: there are plenty of ways to profit if governments merely transfer their prison addictions to other unnecessary forms of social control. Segal reports:

[M]any companies are trying to diversify. In 2013, Corrections Corporation of America, the country’s largest private prison company, purchased Correctional Alternatives, which specializes in re-entry programs, like work furloughs and home confinement.

“We have continued to look for opportunities in this service area,” a spokesman for C.C.A. wrote in an email. “It aligns with the needs of our government partners, who are increasingly looking to this type of solution.”

Many at this conference were what could be called platform agnostic, including Norix, which describes itself as the country’s largest maker of prison furniture. Its slogan is “Engineered to endure,” and to illustrate the point, the company ran a looping video at its booth featuring inventive assaults on its furniture. One snippet featured a vinyl armchair being slowly squashed down to 10 inches high by a pneumatic crusher.

When the machine slowly uncrushed the chair, it retook its original shape.

“Sales to prisons are flat to down,” said Sandy Heitman, a senior project manager. “But more people are being put into mental health facilities, and that portion of the business has increased.” The same is true, she added, of halfway houses.

We sat on some Norix furniture, which was the opposite of the austere, steel slabs you see in prison documentaries. Norix still makes that style of product, but it was highlighting a vinyl collection that comes in lively colors that the company calls lime, mango, orchid and reef. The furniture is intended to be more “humanizing,” a word that is prominent on the company’s website.

“This is a more healing environment,” Ms. Heitman said, gesturing to the products.

As she spoke, the video showed a man in a lab coat jackhammering a chair.

Segal’s article provides a powerful jumping off point for two important questions that long-time prison reformers should be grappling with:

- How much of our support from unexpected allies comes from a real desire to treat other people humanely and how much comes from a desire to tweak the system in order to simply create new avenues for profiting off of other people’s pain?

- How many of the “reforms” currently being considered in this country are no more innovative than taking a sleeping slab and coloring it mango?

Schenwar's book Locked Down, Locked Out is as much about her personal experience with the prison system as it is about her extensive knowledge.

by Elydah Joyce,

August 25, 2015

At the center of Maya Schenwar’s book are the personal truths written to her from the confines of the prison nation. It is from these selected words, transcribed from correspondences with Lacino Hamilton, an incarcerated man from Detroit, that Schenwar’s core message shines through, “Human lives are what weighs in the balance…what are we waiting for?”.

At the center of Maya Schenwar’s book are the personal truths written to her from the confines of the prison nation. It is from these selected words, transcribed from correspondences with Lacino Hamilton, an incarcerated man from Detroit, that Schenwar’s core message shines through, “Human lives are what weighs in the balance…what are we waiting for?”.

Locked Down, Locked Out is a piercing breakdown of the “prison nation” we live in today and the complexities of working towards a future free of these walls. The scope and depth of Locked Down, Locked Out make this short 200-page read a great introduction for a beginner or a great addition to one’s growing collection of prison justice literature. Divided in half, the first part of this book lays out the details of a nation that has come “apart”, taking distorted notions of safety and protection to obscure the realities of a system that is failing people at every turn. The second half is hopeful, exploring what it means for communities to come “together” and struggle for a brighter future.

Early on, it becomes clear that this book is as much about Schenwar’s personal experience with the prison system as it is about her extensive knowledge. She did not write this book just as a theorist or activist, but also as a directly affected member, recognizing the reality of prison: “prison doesn’t stop at the bared wire fence, and it doesn’t end on a release date.” Further, Schenwar doesn’t shy away from the deep racism of the prison nation, constantly highlighting that she and her family’s experience of the prison industrial complex comes from a privileged position of being both white and middle class in a nation where the justice system is, bluntly put, “a modern version of the slave auction book.”

The hardships of Schenwar’s personal relationship with the prison system take a brighter turn in “Coming Together”, the second portion of the book. Here, Schenwar dives into the complexity of dismantling the prison nation, as she explores the relationships between families, prison activists, those incarcerated, and the hundreds of thousands caught in the wider net of correctional control. For example, when speaking about abolition-based action, she describes how successful efforts to close multiple state facilities led to ultimate overcrowding and even higher limitations on medical access for the incarcerated, placing the burden of “progressive” change on those locked inside. Schenwar’s support for prison abolition is undeniable, but she is always mindful of its complexities because “when it comes to decarceration, a victory is never the end.”

Nevertheless, victories are still necessary, and Maya Schenwar spends the final half of Locked Down, Locked Out detailing how to tear down the walls created by the grim isolation, failure and cruelty of the USA’s carceral state. The prison nation is not the finale to this country’s dark history. From halting the school-to-prison pipeline with Peace Rooms to removing the state’s ability to ‘punish’ crime through community-led transformative justice circles, Schenwar leaves the reader with hope that the prison nation is a destructible wall gradually but surely being broken down.

by Stephen Raher,

August 20, 2015

Providing financial services to people in prison has become big business. Prisons, phone companies, and other contractors are reaping huge profits at the expense of incarcerated people and their friends and relatives.

As the operator of one of the largest prison systems in the country, the federal Bureau of Prisons (“BOP”) should be at the forefront of ensuring fair treatment of people who use prison financial systems. But are they? No, in fact they’re actively working to tear down existing protections.

Instead of proactively addressing problems like high fees for money transfer or release cards, the BOP has recently issued a proposed rule that would make it easier for the government to obtain private financial information from those who send money to people in prison. The rule would unilaterally declare that anyone who sends funds to a commissary account “agrees” to release ill-defined “transactional information” to the BOP.

The BOP’s proposed rule is not only bad policy, it goes against privacy rights established decades ago by the federal Right to Financial Privacy Act (the “RFPA”). RFPA protects consumers by prohibiting banks from sharing customer financial records with the government unless the customer is first given a notice and the opportunity to object. And the law still provides numerous ways to legally obtain the financial records if the BOP suspects illegal activity. But rather than using these available methods, the BOP proposes to force people to consent to disclosing their banking records—exactly the kind of coercion RFPA prohibits.

RFPA is clear: even though financial privacy is protected, the government can still access records to investigate crime. So we’re left to conclude that the BOP’s proposed rule is based on the presumption that anyone who sends money to someone in prison is engaged in an unlawful activity. This is untrue and offensive. Family and friends send money to loved ones in prison to help pay for phone calls or basic food and hygiene items (all generally priced at more than the incarcerated folks can afford on their own). No one should be forced to surrender their federally-recognized right to privacy just because the family member or friend they’re supporting is incarcerated.

And the repercussions wouldn’t be limited to the world of prisons. If the BOP can evade privacy laws, what other government agencies will follow? Can someone be forced to let the government go through their bank records simply because they receive unemployment benefits? What about people who pay parking tickets or other fines? Or recipients of tax refunds? Not only does the BOP’s proposal trample financial privacy rights of family and friends of incarcerated people, but it threatens to undermine those rights for all.

The BOP is accepting comments until September 8, 2015 and the Prison Policy Initiative is working on a letter with our allies.

Jerry Miller, known for closing Massachusetts's prisons for kids in 1972 and for book "Search and Destroy: African-American Males in the Criminal Justice System" dies at age 83.

by Peter Wagner,

August 17, 2015

On August 7, Dr. Jerome G. Miller, a visionary in juvenile justice reform, passed away at the age of 83. Jerry Miller is most famous for having closed Massachusetts’ prisons for children in 1972. Hired by Republican Governor Sargent to reform the brutal, inhumane and ineffective “reform schools”, Miller soon discovered that the only option was to close the facilities and to transfer the children to far less restrictive custody, including sending them home. The “Massachusetts Experiment”, as it came to be known, later became a model for reform in other states and is documented in his memoir Last One Over the Wall: The Massachusetts Experiment in Closing Reform Schools.

Jerry Miller’s work first came to my attention when I discovered his second book, Search and Destroy: African-American Males in the Criminal Justice System. The book directly confronted the critical question: Does the evidence prove that the criminal justice system is deliberately racist? Published in 1996, the book is quite dated now, but Search and Destroy played a key role in arguing that the criminal justice system needed to be viewed with a racial justice lens, back when racial disparities were not widely accepted as a defining characteristic of our justice system.

Read other obituaries of Jerome G. Miller:

Most of the people who go to prison or jail in a year go to jail, so why don't policymakers pay more attention to jails?

by Peter Wagner,

August 14, 2015

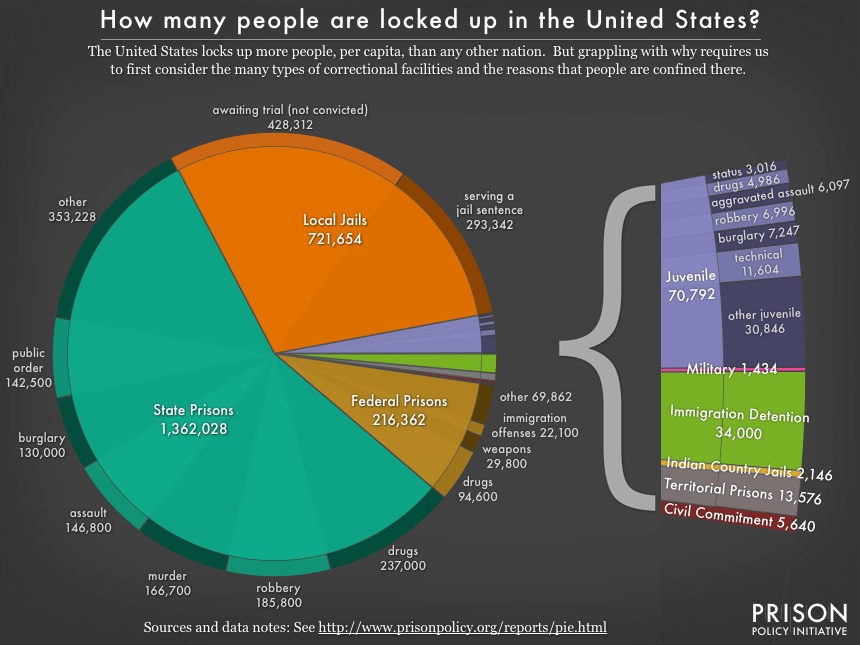

One out of every three people who are locked up tonight are sitting in a local jail, not a state or federal prison. There are 3,283 jails in America, yet jails receive scant attention. The legislative, judicial and executive decisions that have fueled the explosion of our state prison populations are becoming well-known; but the myriad of subtle policy decisions that have sent our jail populations upwards are off the public’s radar.

One out of every three people who are locked up tonight are sitting in a local jail, not a state or federal prison. There are 3,283 jails in America, yet jails receive scant attention. The legislative, judicial and executive decisions that have fueled the explosion of our state prison populations are becoming well-known; but the myriad of subtle policy decisions that have sent our jail populations upwards are off the public’s radar.

Jails need to be a policy focus, as the Vera Institute of Justice recently argued in its aptly-titled report Incarceration’s Front Door: The Misuse of Jails in America.

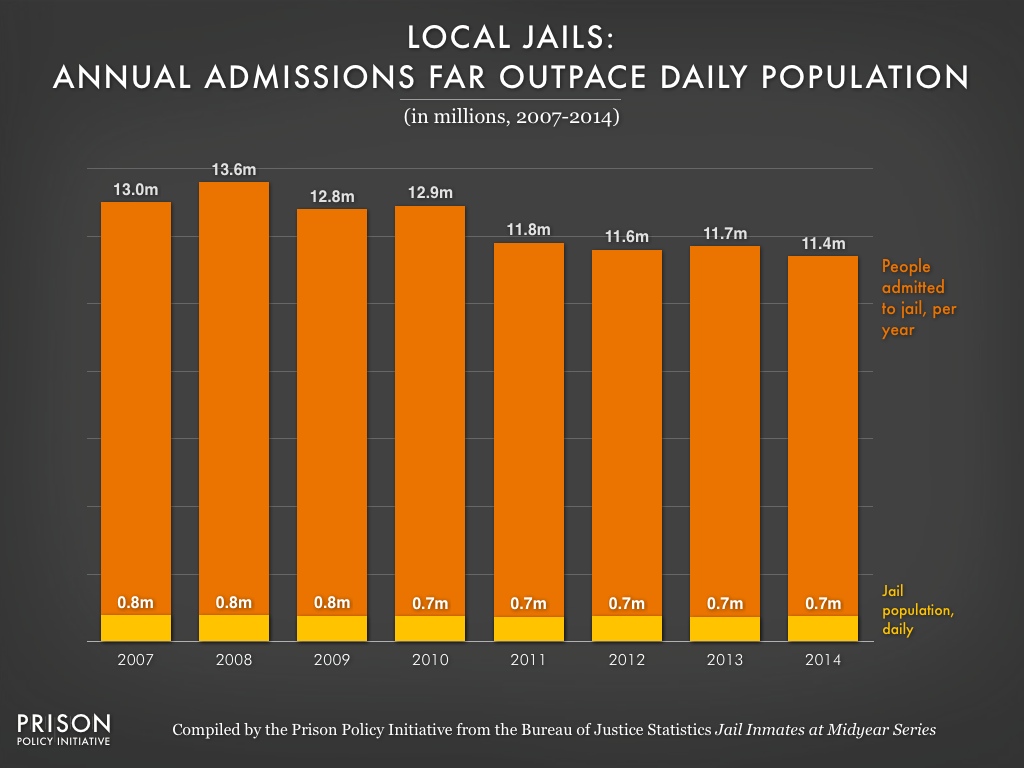

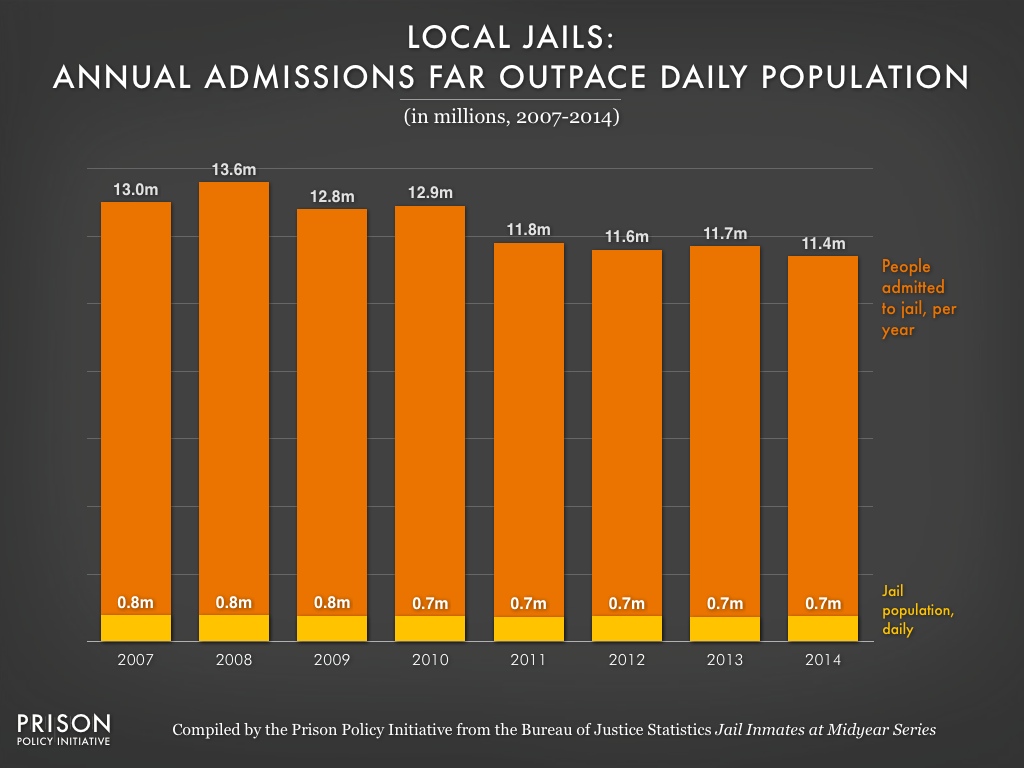

Jails matter because a staggering 11 million people cycle through them each year. As we explained last year:

Jail churn is particularly high because at any given moment most of the 722,000 people in local jails have not been convicted and are in jail because they are either too poor to make bail and are being held before trial, or because they’ve just been arrested and will make bail in the next few hours or days. The remainder of the people in jail — almost 300,000 — are serving time for minor offenses, generally misdemeanors with sentences under a year.

So when we talk about jails we have to keep our eye on two numbers: the number of people in jail on a given day and the sheer volume of people who cycle through them as shown in this analysis of Bureau of Justice Statistics data:

Addressing the problem of jails means grappling with the tremendous churn through jails. How can we lessen the numbers who enter jails and reduce the time that 11 million people spend there each year?

Addressing the problem of jails means grappling with the tremendous churn through jails. How can we lessen the numbers who enter jails and reduce the time that 11 million people spend there each year?

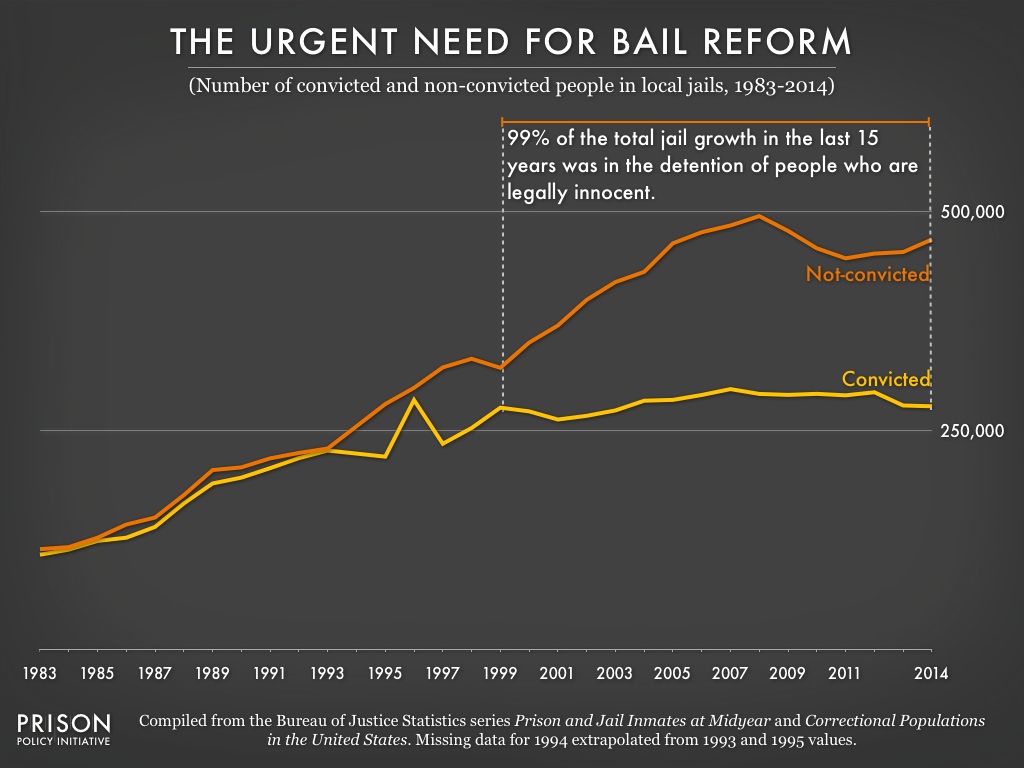

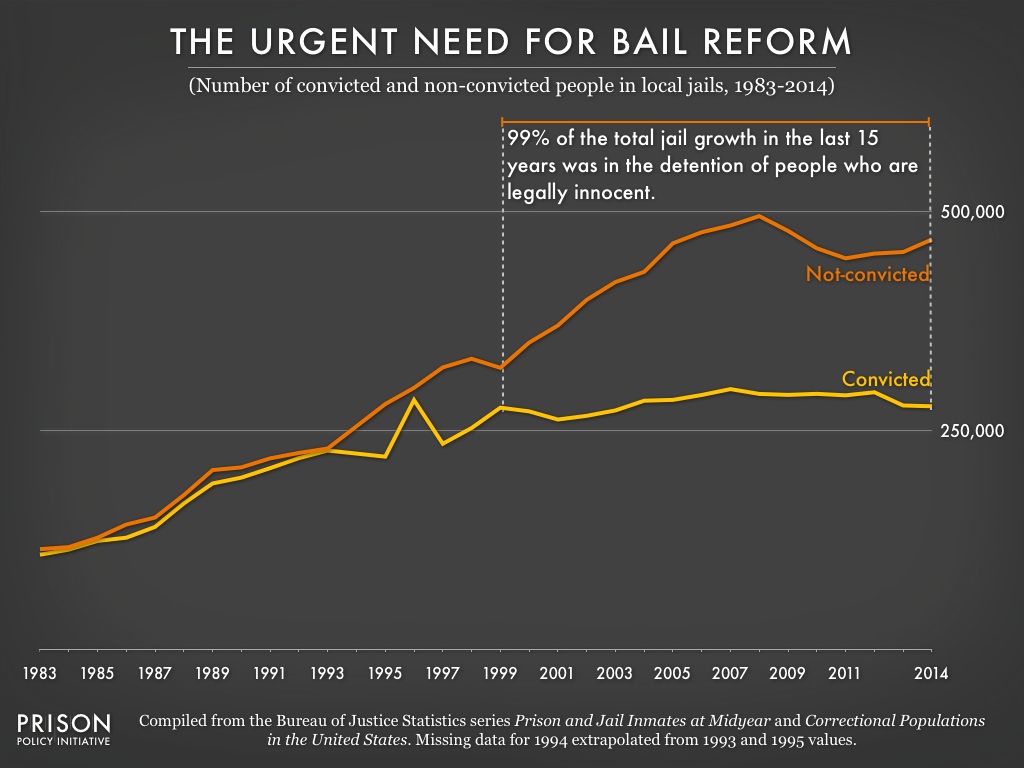

This “pre-trial” or “unconvicted” population is driving the growth in jail populations. In fact, 99% of the growth in jails over the last 15 years has been a result of increases in the pre-trial population:

Virtually all of the growth in the jail population has been in the number of legally innocent people who are detained in jails.

Virtually all of the growth in the jail population has been in the number of legally innocent people who are detained in jails.

These people are legally considered innocent until proven otherwise in court. But if they don’t have the money to post bail, the principle that they are legally innocent is not enough to keep them from being locked up until trial. A recent New York Times feature found that poverty is a frequent cause of pre-trial detention: in New York City even when bail is set at $500 or less, 85% of defendants were unable to afford bail.

Besides the injustice of our jails resembling modern day debtor’s prisons, excessive bail can have other harmful effects. Family life is disrupted, jobs and housing can be lost, and the combined effects can literally be fatal. Pre-trial detention also coerces people to plead guilty to minor offenses, including people who are factually innocent like the man featured in the New York Times article. Studies have also shown that people who are detained pretrial are more likely to be convicted than those who are able to afford bail.

Fortunately, the movement for bail reform is growing in places like New York City and the state of Massachusetts. But at the same time as we work to fix bail, we really should admit that the problem starts even before a bail hearing.

As Peter Goldberg, executive director of the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund put it in the New York Times article:

And the truth is, even meaningful bail reform is just the beginning. The real work is asking why we’re arresting so many people on low-level offenses in the first place, and why so many of them come from poor black and brown communities. Bail is easy.

Or to be more precise: fixing bail should be easy. Why it’s taking so long is a good question and getting to the bottom of this country’s jail problem is going to depend on both reducing the number of people we send to jail each year and making it far easier for those who have been arrested to resume their lives while the judicial process proceeds.

Why is Securus one of the largest campaign contributors to the Sacramento County Sheriff?

by Peter Wagner,

August 12, 2015

Sacramento County, California’s jail confines 4,100 people on a typical day, so the selection of the sheriff should be a big deal for Sacramento residents, yet the leading campaign contributor is a company from Texas.

Dallas-based Securus apparently has a strong interest in who gets to be the Sacramento County Sheriff, so much so that the prison and jail telecommunications giant has been giving $10,000 a year to the Sheriff’s reelection fund for at least the last 3 years, as we describe in a letter sent this morning to the Federal Communications Commission.

Now what’s especially interesting about this is that Securus doesn’t currently have a relationship with Sacramento County; in fact, the county’s current phone contract is with competitor ICSolutions. We wouldn’t be surprised to see the contractor change soon, though, as new bids for the contract were due in July.

Now what’s especially interesting about this is that Securus doesn’t currently have a relationship with Sacramento County; in fact, the county’s current phone contract is with competitor ICSolutions. We wouldn’t be surprised to see the contractor change soon, though, as new bids for the contract were due in July.

As the Federal Communications Commission prepares for a new ruling on regulating the industry, our letter addresses one of the more controversial issues: What should the FCC do about the commissions currently demanded by the facilities in exchange for awarding monopoly contracts to the prison and jail telephone companies? The demand for commissions is at the root of the dysfunction in the prison and jail telecommunications market, but we believe banning the commissions is not necessarily the solution.

We argue that the FCC can simply ensure that the rates and fees charged are reasonable and leave the companies and the facilities to fight over whether and how to share the reasonable profits that remain. (Relatedly, one also has to wonder if things like campaign contributions could possibly explain part of the discrepancy between the tiny profits that Securus tells the FCC it makes and the huge profits that Securus claims before its investors. )

In fact, ensuring that the rates are reasonable is the approach the FCC already took when they regulated inter-state calls, capping the charges for the calls and declaring that commissions were not a legitimate cost that could be used to justify higher rates.

Put simply, the FCC should ensure fair rates for families; that’s best achieved through direct regulation of rates and fees, not by trying to iron out every misaligned incentive in the market.

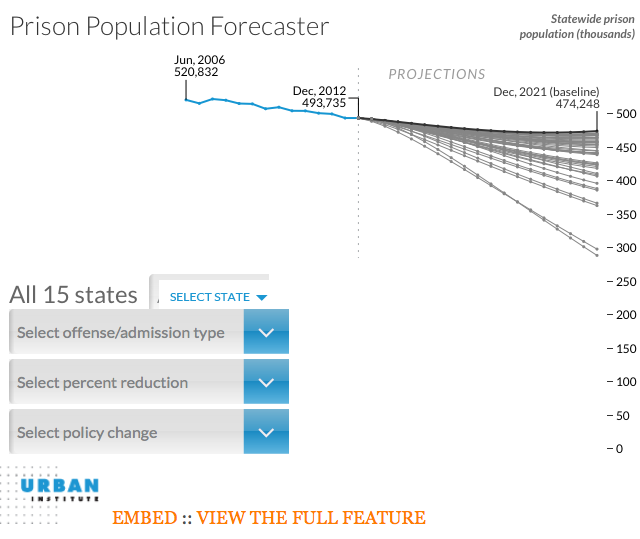

New tool empowers the public to engage the policy choices needed to end mass incarceration. Statistics degree not required.

by Peter Wagner,

August 12, 2015

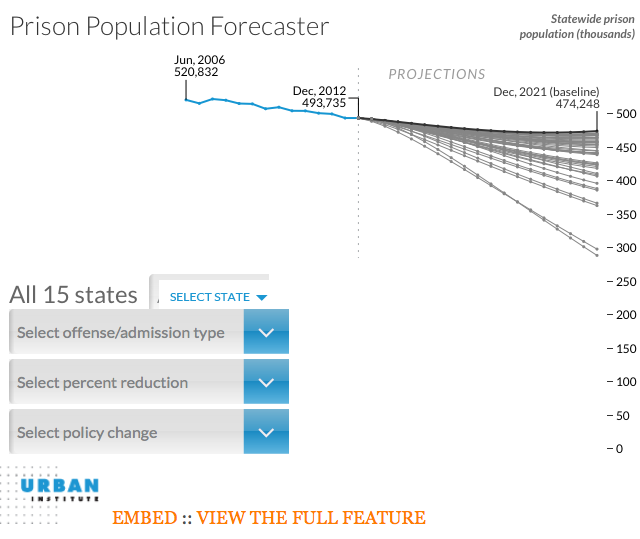

The Urban Institute just published the excellent Prison Population Forecaster:

This interactive tool and article uses data from 15 states to model the impact of various types of reforms to state criminal justice policies. The Forecaster brilliantly makes a very important point: There is plenty of low hanging fruit left that most states can use to lower their prison populations, but making a real dent in mass incarceration is going to also require some tough policy choices.

And now, with the Forecaster, you don’t need to have a degree in statistics to see what the results of particular policy changes might be. Anybody can do it. By empowering more people to access the data, the Urban Institute has made these critical policy choices all the more accessible.

Probation shouldn't be ignored: It's used too often and sets up too many people to fail.

by Peter Wagner,

August 11, 2015

Last week, Shaila Dewan had a brilliant story in the New York Times about how probation sentences set people up to fail: Probation May Sound Light, but Punishments Can Land Hard. The article follows a woman who was arrested for drunk driving, her first offense of any kind, and whose life entered a very expensive spiral, including the loss of two jobs and having to pay almost $4,000 in fees, fines, and court costs and $2,000 to post bail. In addition, she was forced to spend 34 days in the dirty, dank, dangerous and disgraceful Baltimore jail simply because she was unable to find attendance slips from her required A.A. meetings, and she could not afford another $2,500 bail bond to get out of jail time.

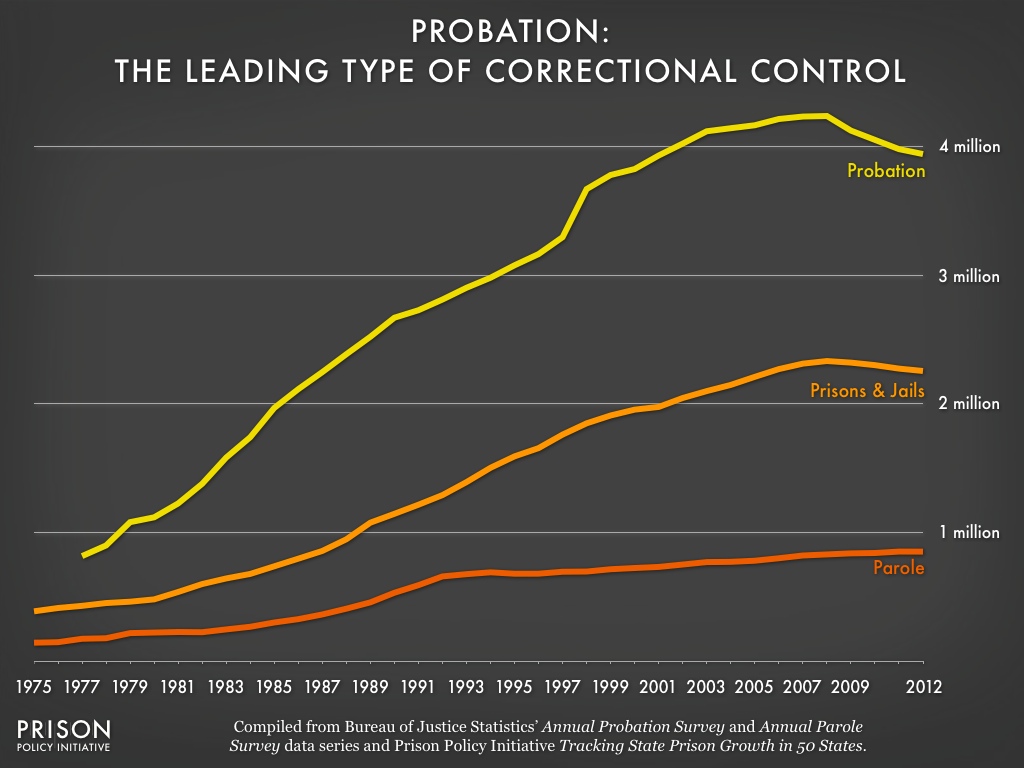

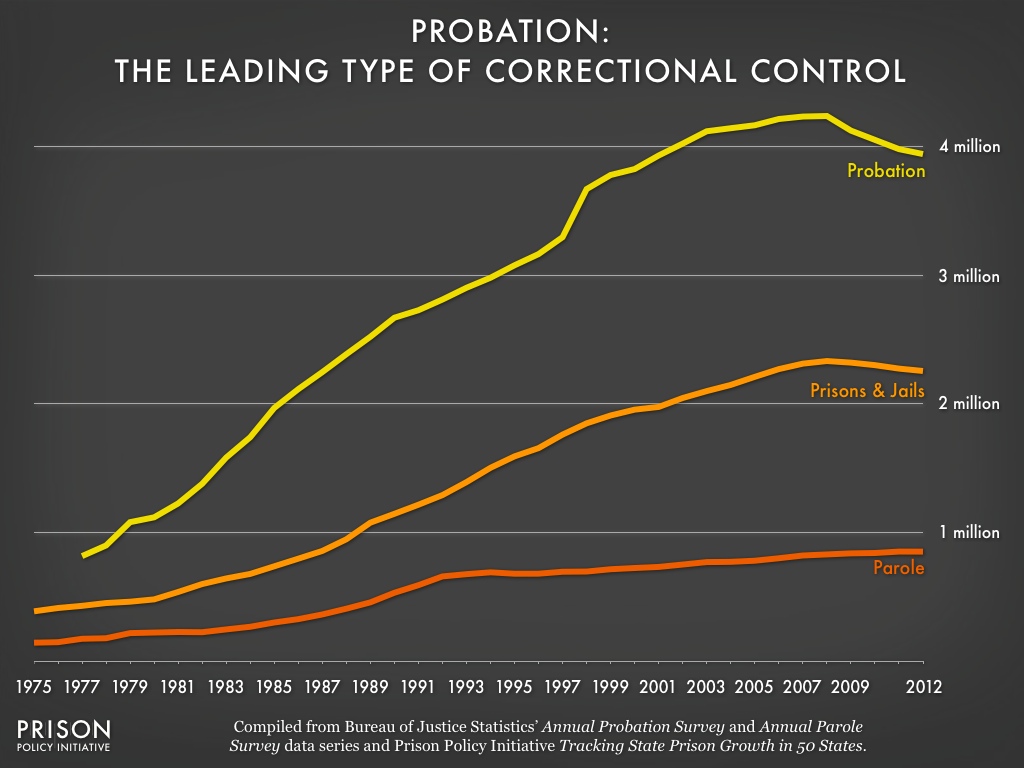

Because many people on probation fail to meet the conditions of their community supervision, probation often isn’t the alternative to incarceration it’s made out to be. The harm of probation would be important even if probation were rare; but more than half the people under correctional control are on probation.

Since the beginning of the statistics almost 40 years ago, the probation population has grown much more quickly than either the number of people on parole or the number of people in federal, state and local prisons and jails. While about 2.3 million U.S. residents were behind bars in 2012, almost 4 million residents were under probation.

Since the beginning of the statistics almost 40 years ago, the probation population has grown much more quickly than either the number of people on parole or the number of people in federal, state and local prisons and jails. While about 2.3 million U.S. residents were behind bars in 2012, almost 4 million residents were under probation.

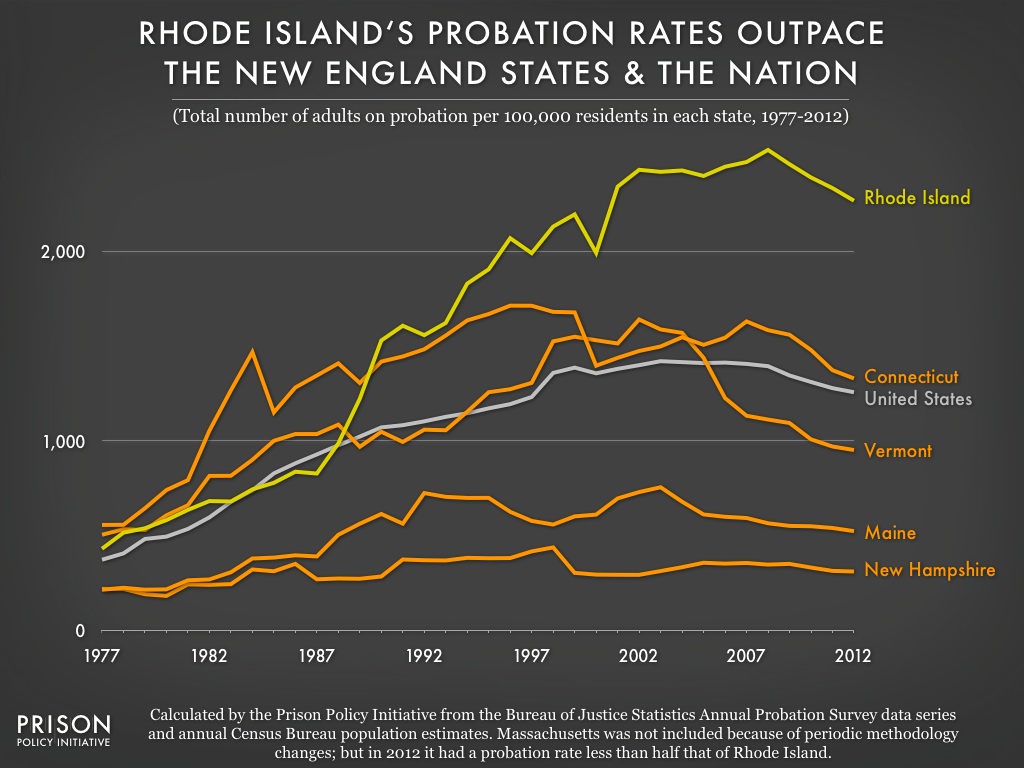

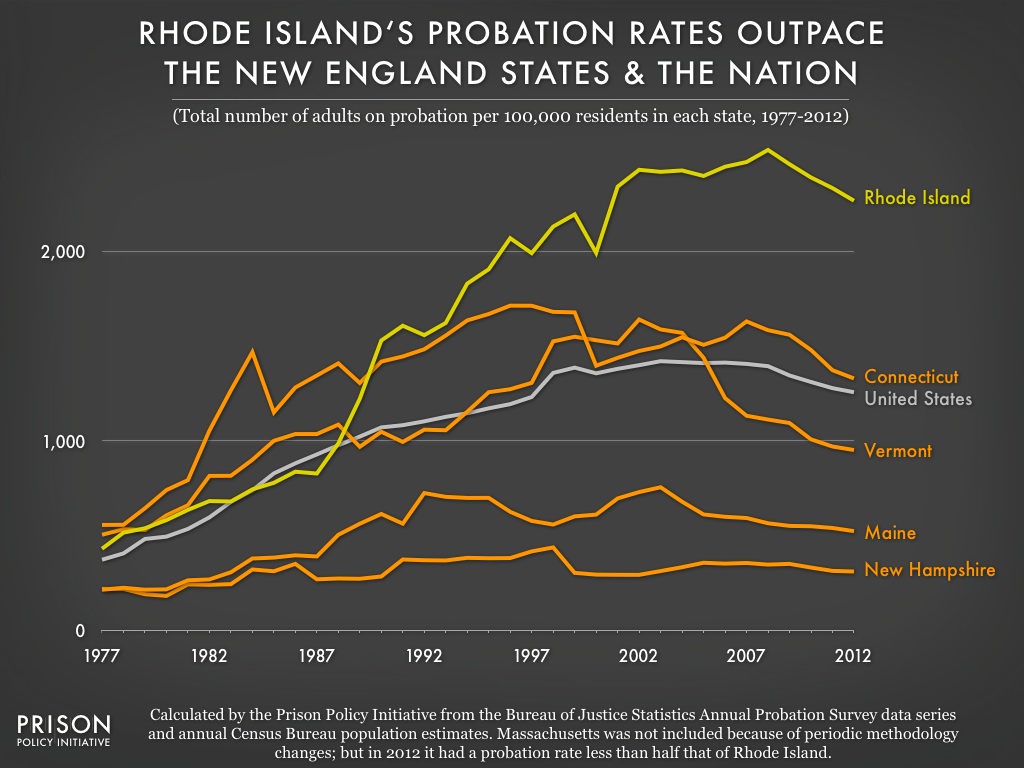

Like imprisonment, there is tremendous variation between the states on the use of probation, but these differences aren’t parallel. For example, Rhode Island has the 48th highest incarceration rate, but the third highest rate of probation.

As the Council of State Governments’ Justice Center has shown, Rhode Island’s probation sentences are 53% longer than the U.S. average, and it’s one of 14 states that doesn’t cap how long probation sentences can be. (Thirty-two states have limited probation sentences to no more than 5 years.) Further, the Justice Center says that they have anecdotal evidence that probation isn’t being used as an alternative because “a large portion of felonies receive split sentences” that include both prison and probation.

Last month, Rhode Island’s governor created the Justice Reinvestment Working Group in order to get to the bottom of the state’s use of probation. One answer I hope the group will uncover as they develop a path to more reasonable uses of correctional control is exactly why Rhode Island decided to leave its neighbors behind in the use of probation:

The rate of probation in Rhode Island is more than twice as high as the rate of probation in most other New England states. (Massachusetts was not included in the graph above because the state changed its reporting methods multiple times during the previous decade. However, in the most current available data, Massachusetts reported a rate of 1,033 adults on probation per 100,000 residents, less than half Rhode Island’s rate of 2,268 per 100,000 residents.)

The rate of probation in Rhode Island is more than twice as high as the rate of probation in most other New England states. (Massachusetts was not included in the graph above because the state changed its reporting methods multiple times during the previous decade. However, in the most current available data, Massachusetts reported a rate of 1,033 adults on probation per 100,000 residents, less than half Rhode Island’s rate of 2,268 per 100,000 residents.)

The 2016 presidential candidates shouldn't underestimate the federal budget's power to guide state justice policy.

by Peter Wagner,

August 10, 2015

With a growing number of presidential candidates calling for an

end to mass incarceration, there has been a flurry of discussions in the press about the role that the Executive Office can play in reversing our nation’s over-use of the criminal justice system. Since most incarcerated people are locked up in state prisons, people have been asking, what can the leader of the federal government do about mass incarceration?

While it turns out that the answer is “quite a bit,” these discussions have largely overlooked the powerful role that the federal budget plays in shaping state policy. Criminal justice policy is no exception. As Inimai Chettiar observed in the Brennan Center for Justice’s Solutions: American Leaders Speak Out on Criminal Justice:

The federal government has been one of the largest instigators of perverse incentives. For example, the 1994 Crime Bill included $9 billion to encourage states to drastically limit parole eligibility. Unsurprisingly, 20 states promptly enacted such laws, yielding a dramatic rise in incarceration. Today, the federal government continues to subsidize state and local criminal justice costs to the tune of $3.8 billion annually.

Given the federal government’s historical role in fueling mass incarceration, Chettiar points out, federal budgetmakers could switch gears to instead incentivize smarter and more measured criminal justice policymaking:

One basic, yet effective, step: The federal government should provide funds to states that cut both crime and imprisonment. California,

Texas, and other states succeeded by changing financial incentives. They

awarded additional funds to local probation departments that reduced

the number of people revoked to prison. In its first year alone, California

reduced revocations to prison by 23 percent, saving the state nearly $90

million. In one year, Texas reduced the number of people revoked to

prison by 12 percent. In both states, crime continued to drop.

To be sure, slowing and reversing the our nation’s unprecedented use of correctional control requires a multifaceted and long-term approach. But as the other 2016 candidates shape their criminal justice policy platforms, they shouldn’t underestimate the federal budget’s power to steer state justice policy in a positive direction.

Addressing the problem of jails means grappling with the tremendous churn through jails. How can we lessen the numbers who enter jails and reduce the time that 11 million people spend there each year?

Addressing the problem of jails means grappling with the tremendous churn through jails. How can we lessen the numbers who enter jails and reduce the time that 11 million people spend there each year? Virtually all of the growth in the jail population has been in the number of legally innocent people who are detained in jails.

Virtually all of the growth in the jail population has been in the number of legally innocent people who are detained in jails.

Since the beginning of the statistics almost 40 years ago, the probation population has grown much more quickly than either the number of people on parole or the number of people in federal, state and local prisons and jails. While about 2.3 million U.S. residents were behind bars in 2012, almost 4 million residents were under probation.

Since the beginning of the statistics almost 40 years ago, the probation population has grown much more quickly than either the number of people on parole or the number of people in federal, state and local prisons and jails. While about 2.3 million U.S. residents were behind bars in 2012, almost 4 million residents were under probation. The rate of probation in Rhode Island is more than twice as high as the rate of probation in most other New England states. (Massachusetts was not included in the graph above because the state changed its reporting methods multiple times during the previous decade. However, in the most current available data, Massachusetts reported a rate of 1,033 adults on probation per 100,000 residents, less than half Rhode Island’s rate of 2,268 per 100,000 residents.)

The rate of probation in Rhode Island is more than twice as high as the rate of probation in most other New England states. (Massachusetts was not included in the graph above because the state changed its reporting methods multiple times during the previous decade. However, in the most current available data, Massachusetts reported a rate of 1,033 adults on probation per 100,000 residents, less than half Rhode Island’s rate of 2,268 per 100,000 residents.)