Unpacking the connections between race, incarceration, and women’s HIV rates

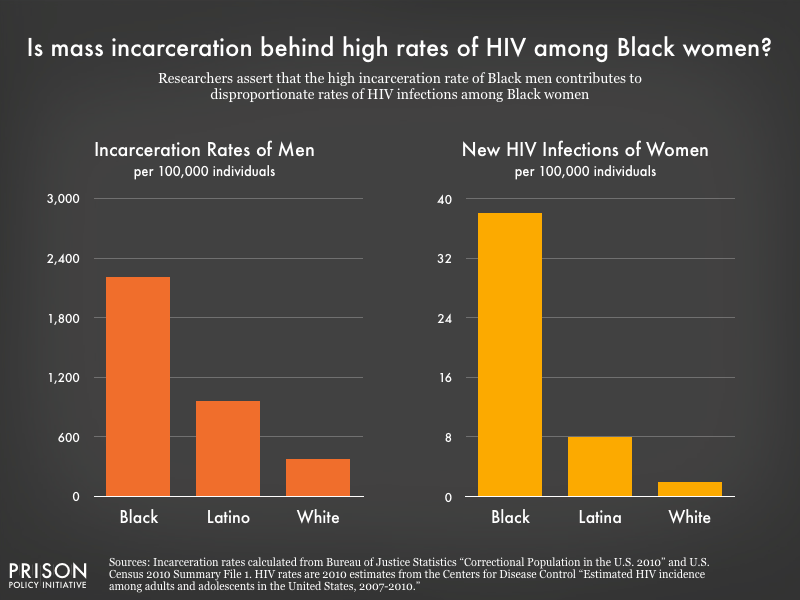

Current research points to an unexpected contributor to the high rates of HIV infection among Black women: the mass incarceration of Black men.

by Wendy Sawyer and Emily Widra, May 8, 2017

Over 7,000 women in the United States received a new HIV diagnosis in 2015, and over 60% of those women were Black, despite the fact that Black people represent just 12% of the overall U.S. population.

While policymakers seem oblivious to this pressing health problem, Prof. Laurie Shrage’s 2015 New York Times op-ed drew our attention to research that unravels the complicated nature of HIV risk factors among Black women. In general, Black men and women report less risky drug use and less risky sexual behaviors than whites; so what accounts for the disproportionately high number of HIV infections among Black women?

From researchers, an unexpected explanation

The current interdisciplinary research points to an unexpected explanation: the mass incarceration of Black men.

Two University of California professors, Rucker Johnson & Steven Raphael investigated the complicated relationship between infection rates and incarceration. Their findings reveal that “the lion’s share of the racial differentials in AIDS infections rates for both men and women are attributable to racial differences in incarceration trends.”

The “trend” in question, of course, is the hyper-incarceration of Black men over the last few decades. Between 1974 and 2001, the likelihood of incarceration for Black men increased from 13.4% to 32.2%. The racial disparity is now extreme: in 2015, Black men were almost six times more likely to be incarcerated than white men.

Johnson and Raphael (2009) conclude that if it weren’t for the racial disparity in male incarceration, Black women would have lower rates of HIV infection than white women.

Johnson and Raphael (2009) conclude that if it weren’t for the racial disparity in male incarceration, Black women would have lower rates of HIV infection than white women.

To explain the connection between the disproportionate incarceration of Black men and the HIV rates of non-incarcerated Black women, Johnson and Raphael point to:

- high rates of HIV in prisons

- risky sexual activity among men in prisons

- sexual networks with a large number of lifetime partners

- destabilized relationships (defined by periodic absences of the incarcerated partner), and

- a disproportionate ratio of non-incarcerated Black men to women.

To begin with, they found that the rates of risky sexual activity, and therefore the risk of HIV infection, among incarcerated men is significantly higher than in non-incarcerated populations. In particular, the sexual networks in prisons – where “a small number of individuals have repeated sexual encounters with a large number of partners” – increases the efficiency of HIV transmission. And considering that condoms are widely considered contraband in correctional facilities, the risk for STIs is heightened regardless of the number of sexual partners.

Women who have a sexual partner with a history of incarceration are at an elevated risk of HIV infection. By forcing partners to spend long stretches of time apart, incarceration often causes breakups or on-again, off-again relationships, increasing the number of lifetime partners – a major risk factor for HIV – for both the incarcerated and non-incarcerated partners.

With 1 in 15 Black adult men behind bars , incarceration also disproportionately reduces the ratio of Black men to Black women. Because the overwhelming majority of sexual relationships and marriages occur between individuals of the same age group, race, ethnicity, and geographic location, this means Black women have less ability to be selective in choosing a partner and/or in negotiating safer sexual behaviors. In particular, heterosexual Black women are more likely to have sexual partners in “high risk groups,” that is, men with a history of incarceration.

Prevention: Improving re-entry services

Incarceration does not just impact the lives of those behind bars; it reaches far into communities, jeopardizing the health status of the partners and families these men return to. This is largely because of the particular vulnerability of formerly incarcerated people when they are first released. At the same time these men are returning to their relationships and families, their risk of transmitting HIV is elevated and their access to treatment is limited.

Dr. Chris Beyrer, former president of the International AIDS Society, explains that “people are being released [from prison] without access to services and they experience treatment interruption,” which in turn causes their viral load to spike. After release, Black men are not connected to structured care in the community to assure treatment adherence (there are some facilities with HIV transitional case management, but not much data on how effective and replicable these programs are.)

In a recent study of HIV care among criminal justice involved individuals in Washington, D.C., researchers found that despite reliable access to HIV treatment providers prior to, during, and after incarceration, HIV treatment adherence drops significantly after being released.

The stigma of HIV infection may also be part of the problem. As Phill Wilson, President of the Black AIDS Institute, explains, “they’re stigmatized because they’re Black, stigmatized because they’re ex-prisoners and they’re stigmatized because they’re HIV positive… What sane person is actually going to disclose that they’re HIV positive?”

The higher risk of HIV infection among women is one of many collateral consequences of mass incarceration facing communities of color. To better protect Black women from HIV infection, we need to eliminate the gap in HIV/AIDS treatment for Black men released from prisons and jails. Correctional agencies should coordinate with community health providers to ensure continuity of care and support treatment adherence. Reuniting with partners and families should improve the well-being of communities, not add to their problems.