New BJS data: Prison incarceration rates inch down, but racial equity and real decarceration still decades away

At the current pace of decarceration, it will be 2088 when state prison populations return to pre-mass incarceration levels.

by Alexi Jones, October 30, 2020

Last week, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) released Prisoners in 2019, an annual report that breaks down the number of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons. Along with the report, BJS released a press release that paints a deceptively rosy picture of mass incarceration in the United States, which has been parroted by numerous media outlets.

The press release boasts that the United States’ incarceration rate (419 per 100,000 people) is at its lowest since 1995, and that Black Americans are incarcerated at the lowest rate in 30 years. But this framing misses the bigger picture: 1.4 million Americans, who are disproportionately Black, are still incarcerated in state and federal prisons — meaning that the prison population is still five times larger than it was in 1975, before the “war on crime” really took hold and the number of people under correctional control exploded.1 Moreover, the slow pace of decarceration, especially for Black people and women, means we are looking at decades more of racially disparate mass incarceration in the United States unless lawmakers are willing to make much bolder changes.

If knowing the historical context is helpful, so is understanding that incarceration goes beyond federal and state prisons. 738,000 people, disproportionately Black, are locked up in local jails as of 2018. That year (the most recent for which BJS has published jail data), there were 4.7 times as many people incarcerated in local jails as there were in 1978. This increase is largely due to the rise in pretrial detention — the jailing of people who are still awaiting trial and haven’t been found guilty of a crime. (The newly-released prison data also obscures the fact that in some places, people who would have been held by state prisons in 1995 are now held by local jails, most notably in California, where this “realignment” was enacted in an effort to reduce prison overcrowding. There and in other states, changes to sentencing structures have shifted people out of prisons but into jails.)

Not only is our state and federal prison population still massive, the data in the report reveals that our pace of decarceration has been stubbornly slow. Recent criminal justice reforms have not been nearly enough to counteract the massive growth of our prison populations over the past forty years. At the current pace of decarceration:

- It will be 2044 when the federal prison population returns to pre-mass incarceration levels — 24 years from now.

- It will be 2088 when state prison populations return to pre-mass incarceration levels — 68 years from now.

- It will take until 2039 for the Black incarceration rate to equal the 2019 white incarceration rate—19 years from now.

- And it will be 2199 when the women’s prison population returns to pre-mass incarceration levels — 179 years from now.

Troublingly, the report shows that, at least in the year before the COVID-19 pandemic, some states were moving backwards. From 2018 to 2019, Indiana’s prison population increased by 1.1%, Alaska’s grew by 2.2%, Georgia’s rose 2.2%, Nebraska’s increased by 3.5%, North Dakota and Alabama both saw a 5.5% increase, and most disturbingly, Idaho’s prison population grew by 8.9%. Even worse, almost all of these states have prison systems that are already overcrowded, or close to their maximum capacity. Nebraska and Idaho’s prisons, for example, are holding 115% and 110%, respectively, of their highest capacity. (During the pandemic, at least some of these states have reduced their prison populations more significantly, but it remains to be seen whether these reductions will last.)

The federal prison system’s population is declining at a faster rate than state prisons, but the report shows that reforms are not going far enough. Nonviolent drug offenses are still a defining characteristic of our federal prison system. In 2019, 46% of people locked up in federal prisons were serving time for a drug offense, while only 8% were serving time for a violent offense.

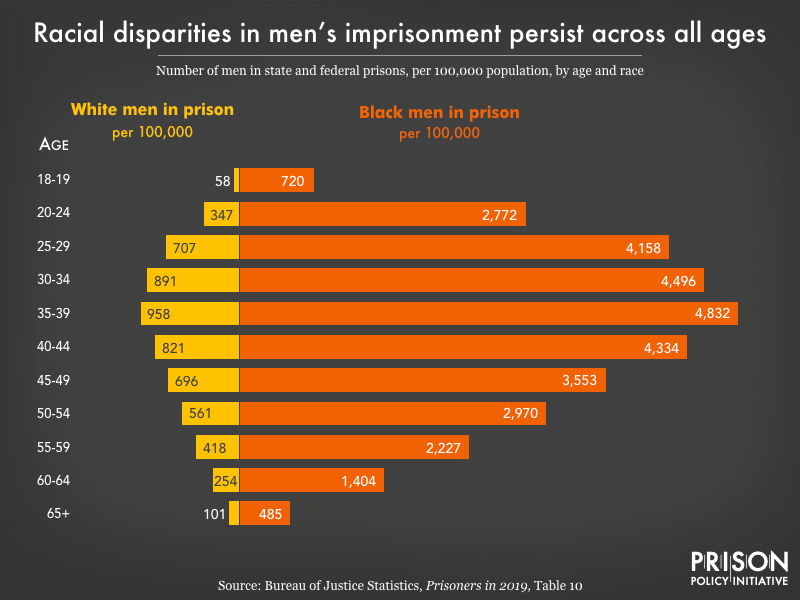

The report also boasts that the Black incarceration rate is at its lowest since 1989. While Black Americans certainly are incarcerated at a lower rate than they have been at other points in U.S. history, it’s important to put these numbers in perspective. Black Americans are still incarcerated in state and federal prisons at five times the rate of white Americans. 1.1% of all Black Americans are incarcerated, compared to 0.2% of white Americans. The numbers are even more disturbing when we focus in on Black men. 1 in 50 Black men are incarcerated, including over 1 in 25 Black men between 25 and 44 years old.

Finally, the report reveals that the women’s prison population is declining at less than half the rate of the men’s population. Between 2009 and 2019, the men’s prison population declined by 1.2% per year, while the women’s population has declined by 0.5%, or 550 people per year. This is despite the fact that women’s state prison populations grew 834% over nearly 40 years — more than double the pace of the growth among men.

Prisoners in 2019 underscores the need for bold criminal justice reforms that dramatically reduce our prison populations and eliminate the pervasive racial disparities in our criminal justice system. And as we have noted before, states must pay special attention to women’s incarceration. Criminal justice reforms are even more urgent as COVID-19 sweeps through prisons and jails across the country, putting millions of lives at risk.

Sources and methodology

The late 1970s is an especially useful point of reference because it is right before the “war on crime” really took hold-incarceration rates had been relatively flat for decades and the number of people under correctional control had not yet exploded. In order to determine our baselines we used incarceration rates to ensure that 1975 was representative of historical trends. We used 1975 as our starting point for the prison population comparisons and projections.

The data for our state and federal prison projections came from the Bureau of Justice Statistics reports Prisoners in 2019 and Historical Statistics on Prisoners in State and Federal Institutions, Yearend 1925-86. For the federal prison population, we used 1975 as our baseline (24,131 people) and 2012 (197,050) as our peak value with an average yearly decline since the peak (6,100/year) to arrive at our projection of 2044. And for the population held in state prisons, we used 1975 as our baseline (216,462) and 2009 (1,365,688) as our peak value with an average yearly decline since the peak (15,168/year) to arrive at our projection of 2088.

For our racial disparity projection, we relied on data in Table 5 of Prisoners in 2019. We used the current incarceration rate for white individuals (214) as our baseline, and focused on the change in the incarceration rate for Black individuals between 2009 (the year prison populations peaked) and 2019, which declined by an average of 44.8 people per 100,000 per year. It would therefore take over 19 years for the Black incarceration rate to reach the 2019 white incarceration rate.

Finally, for women’s incarceration, we used 1975 as a baseline (with 8,675 women in state and federal prisons), and 2009 (113,485 women) as the peak with an average decline of 553 women per year to arrive at our projection of 2199.

Footnotes

-

In 1975, there were 216,462 people incarcerated in state prisons, and 24,131 people incarcerated in federal prisons for a combined population of 240,593. In 2019, there were 1,430,805 million people incarcerated in state and federal prisons. ↩