Going back to Cali: Revisiting California’s parole release system

More than 9,000 people were eligible for hearings in California last year, though the state abolished discretionary parole in 1977. With grant rates among the lowest in the nation and people forced to wait up to 15 years between hearings, the Golden State's parole system is far from glittering.

by Emmett Sanders, December 19, 2023

In 2019, we graded parole release systems across the US. Though no state performed particularly well, the 16 states that have mostly abolished discretionary parole since 1976 received our lowest grade, an F-. California was among them. Advocates from California asked us, however, to take a closer look at California’s parole system. Unlike other states that have abolished discretionary parole, California’s discretionary parole system since 2014 has significantly expanded eligibility for a large number of incarcerated people who meet certain criteria, and more become eligible each year.

We revisited California’s existing parole system to see how it would score using criteria we reserved for states with discretionary parole. In keeping with our more recent parole research, we also examined recent trends in the state’s parole process to see how it is being (mis)used and how often parole hearings actually result in release. While California may score slightly better this time around, ultimately, it still merits a solid “F.”

What makes California different from other states that have abolished parole?

California replaced parole with determinate sentencing for most people in the state’s prison system in 1977.1 As in the 15 other states that have done this, discretionary parole was not entirely abolished. Almost all states that have abolished discretionary parole still retained it for small slices of their prison populations. However, California differs from other states that have abolished parole because it largely determines who is still eligible for parole based on criteria other than the the date that someone was sentenced. When California moved to a determinate sentencing scheme in 1977, it retained life sentences with the possibility of parole for the most serious offenses, such as murder and kidnapping with ransom.

In the other states that abolished discretionary parole, the only people still eligible for parole are those who were “grandfathered in” — that is, who were sentenced before parole was abolished.2 In these states, the number of people eligible for parole shrinks every year, as people are released or die in prison. This is not true in California, where people sentenced for certain very serious felonies and some people sentenced under the Three Strikes Law can still receive life sentences with the possibility of parole. Every year, new people are sentenced who will eventually become eligible for parole. Due to new laws since 2014 that have significantly expanded parole eligibility, including for the elderly and people sentenced as youths, other people can also now become eligible for parole based on factors like their current age, age when convicted, and the amount of time served. As a result of these new laws, almost all incarcerated people now have an opportunity for parole release during their lifetime.

What does parole look like in California?

Every state differs, though elements of California’s parole process are similar to others. In a nutshell,3 the Board of Parole Hearings determines when a person becomes parole-eligible and sets an initial parole suitability hearing. Like in other states, the Board considers factors such as the offense, institutional records, and the results of a comprehensive risk assessment. They often consider input from the DA and survivors of violent crimes. People have access to legal representation, though in 2021, those with state-appointed attorneys were granted parole at half the rate of those with private counsel, which many cannot afford. Unlike Alabama, which denies incarcerated people any access to the parole board, California interviews the person, generally via video. If the Board makes a decision,4 they either grant release or deny it, in which case the person won’t get another hearing for between 3 to 15 years. The number of times the board may see a person is bound only by the duration of their sentence, so those with lengthy or life sentences are often reviewed and denied many, many times.

How many people does this affect?

In 2022, there were 9,017 scheduled hearings, up 49% since 2019, when there were 6,061. Meanwhile, the prison population in the state dropped by around 21%. Not only did the percentage of the prison population that was eligible for parole actually increase from around 5% in 2019 to more than 9% by 2022, but it made up almost a quarter of everyone who was eligible for release from California prisons by any means that year. Because of California’s low grant rate, however, people released on parole accounted for just 4% of all people released from California prisons in 2022.

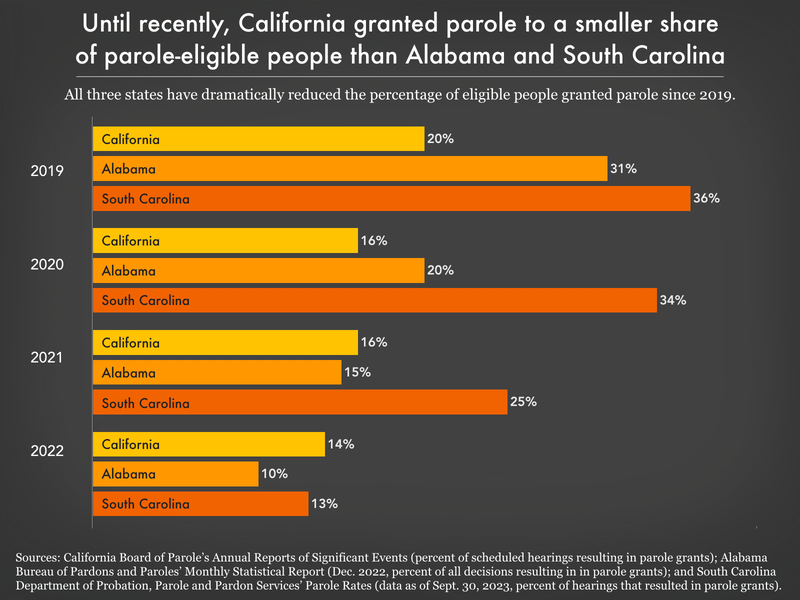

Parole grant rates 2019-2022

California has made several recent moves to expand parole eligibility. However, these efforts appear to have been undermined by a parole board reluctant to release anyone. California’s actual grant rate,5 the percentage of scheduled parole suitability hearings that resulted in parole approval, was just 14% in 2022, barely above South Carolina (13%) and Alabama (10%) for the worst among those we examined.6

From 2019 to 2022, California’s actual parole grant rate fell 29%. Additionally, while hearings increased significantly, the vast majority of new hearings resulted in non-decisions, which increased by 75%, and denials, up by 41%. Ultimately, nearly 3,000 more hearings resulted in only 75 more people being released in 2022 compared to 2019, making the likeliest outcome of a parole hearing in California, by far, continued incarceration.

Grading California

Even adjusting for its limited use of discretionary parole, California’s parole system is more box office bomb than Hollywood hit. Overall, the state scored just 60 out of 120 possible points, earning only a slightly higher F than in the original report. While there were a number of issues here, three stood out as particularly egregious:

- Prosecutorial influence: Prosecutors often attend hearings and heavily influence the outcome. In 2022, prosecutors attended 60% of hearings held. The hearings attended by prosecutors resulted in about 24% fewer grants than when prosecutors did not attend.

- Extremely lengthy time between hearings after denials: Incarcerated people have to wait a minimum of three years and sometimes up to 15 years between denials.

- Unequal weighting of risk-assessment results: While California does issue a detailed annual report, there are massive deviations between the risk-assessment results, which are supposed to weigh heavily on the guidelines, and actual hearing outcomes. In 2022, people deemed “Low Risk” were paroled only 65% of the time, while folks with “Moderate Risk” were granted parole only 22% of the time, and those deemed “High Risk” were almost never paroled <1%. This suggests that negative risk assessments weighed far more against people than positive risk assessments did in their favor.

Moving forward: Ways California could improve its system

- Reduce the time between all hearings to no more than 1 year: Setting time between denials to up to 15 years fails to take into account changing policies, people, or parole board compositions. Additionally, the discrepancy in time between denials vs. time between waivers (1 to 5 years) encourages people to self-select.

- Eliminate reliance on “fixed-moment factors” and increase focus on objective factors that are better suited to measure personal growth and mitigated risk. Like many parole boards, California’s guidelines for parole consideration place heavy emphasis on “fixed-moment factors” — such as the crime of conviction, the person’s actions, and even their mental state during the commission of the crime — which are unchangeable regardless of effort on the part of the incarcerated person or the passage of time. These are ill-suited to measure things like personal growth or the risk a person might pose if released.

Conclusion

Though partially abolished almost 47 years ago, California’s discretionary parole system is alive and unwell as 2023 draws to a close. More and more people find themselves parole-eligible each year, and many are denied their chance at freedom and are forced to wait a decade or more before applying again. Ultimately, though parole does exist in some form in California, it is far from being at the head of the class.

Footnotes

-

Determinate Sentencing describes a fixed-sentence system where people have a set number of years to do, and do not have the ability to be individually evaluated for early release. Their release date may be modified by awarding time credits for things such as good conduct or program completion or by revoking them generally for disciplinary reasons. Truth-in-sentencing laws have severely limited and, in many cases, have eliminated entirely the amount of time credit that can be earned. ↩

-

Some states have more recently expanded discretionary parole, largely for juvenile lifers after a set amount of years. While this work is certainly worth noting, these moves have generally had a more limited effect. ↩

-

See Prison Law Office’s The California Prison and Parole Law Handbook (2019) for a more in-depth look at California’s parole process. ↩

-

In 2022, only 49% of scheduled hearings resulted in grants or denials. The majority resulted in “non-decisions,” outcomes where no decision is made to grant or deny parole, either due to continuances or to “voluntary” waivers and stipulations — 29% of all outcomes in 2022. For context, a “voluntary waiver” allows a person to waive their hearing for between 1-5 years. In contrast, a denial at a parole hearing means they must wait 3, 5, 7, 10, or even 15 years for another chance at parole. This disparity creates a coercive situation for incarcerated people that is akin to a plea bargain system — if a person fears they are likely to be denied parole, they are strongly incentivized to waive a hearing rather than risk a far lengthier time in custody. While these waivers are described as “voluntary,” we think it would be disingenuous to ignore the coercive nature of the system. ↩

-

“Actual Grant Rate” is determined by dividing the number of parole applications granted by the number of scheduled hearings in which release is a possible but not mandated outcome. While California notes both actual grant rates and “grant rates for hearings held”–which only include approvals and denials–in annual reports, like in many states, the latter metric is more publicly used. Omitting outcomes where no decision was reached (non-decisions) artificially raises the reported grant rate. Non-decisions, however, always result in continued incarceration. ↩

-

Neither Alabama nor South Carolina includes non-decisions in their calculations, meaning that their actual parole grant rates are likely considerably lower. ↩