Cautionary jails: Deconstructing the three “C”s of jail construction arguments

Communities across the country have been told that investing in new jail construction is the only way to solve old policy problems, but arguments for new jails can leave them with a billion-dollar case of buyer’s remorse.

by Emmett Sanders, February 20, 2024

Arapahoe County, Colorado, is expanding its jail just four years after taxpayers rejected a proposition to raise taxes for a new one. The justification for the $46 million expansion? Proponents cite the jail’s age, overcrowding, and a sudden sensitivity to the need to treat rather than warehouse people with addiction issues; the sheriff claims, “people’s needs have changed.” $30 million will come from COVID-19 pandemic relief funds; 1 as the ACLU notes, using relief funds in this way is expressly forbidden by the Department of Treasury.

Similar arguments are being used to justify jail construction all around the country. Often, this means ignoring voters’ wishes, misusing and redirecting millions of dollars from community-based resources, and saddling citizens with decades of tax liability. New jail construction projects regularly fail to meet promises, leaving communities to deal with the aftermath. Drawing from examples across the country, we break down three common arguments for jail construction, discuss how they have been used to build or expand jails, and highlight how reinvesting in cages is not a solution to social problems like crime and substance use.

The three “C’s” of jail construction arguments

Jail proponents usually rely on one or more of three central arguments to make their case:

- The “Capacity” argument: a bigger jail is required to house everyone being incarcerated in the jurisdiction;

- The “Contemporary” argument: new construction is needed to update an outdated jail;

- The “Compassionate” argument: new construction is necessary to treat incarcerated people more humanely.2

On a surface level, these three “C” arguments are compelling because they speak to very real issues. What these arguments often overlook, however, is that these issues are largely driven by bad policies that have drastically expanded reliance on packing people in cages. Essentially, the prevailing claim is that the only way to solve the problem of incarceration is to expand our ability to incarcerate — when in fact, communities would be better served by shrinking jail populations. This sunk cost fallacy often leaves communities without real solutions and holding the bag for decades.

If you build it… (the “capacity” argument)

Proponents of jail construction often rely upon jail “needs assessments”3 to bolster their claim that building a bigger jail is the only way to meet capacity needs. These needs assessments come with many biases and flaws — often because they are written by construction firms who hope to eventually make even more money building the new jail. The simple truth is that no jail will ever be big enough to satisfy an over-reliance on incarcerate-first policies. Instead of solving capacity needs, bigger jails enable counties to continue bad practices — leading them to argue that they need newer, even bigger jails in the future, and spending millions of dollars in the process.

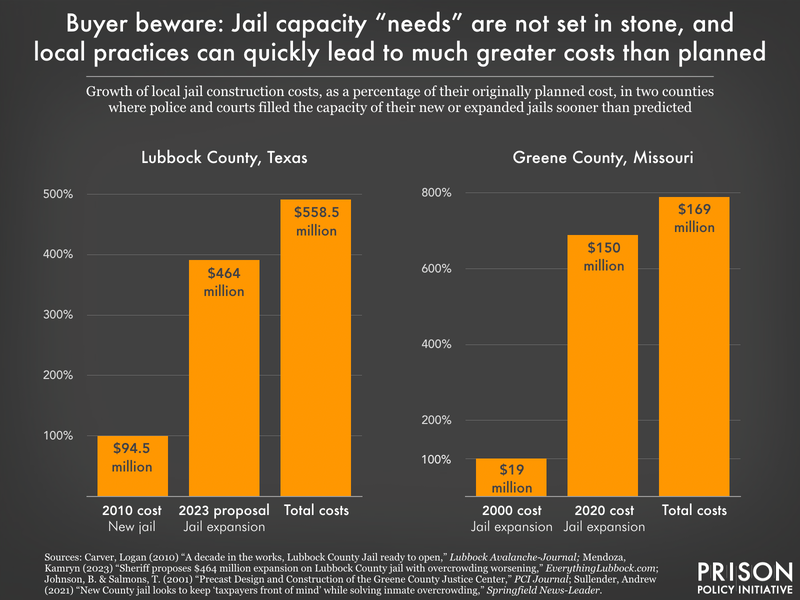

Greene County, Missouri, for instance, built a new 552-bed jail in 2001. This was supposed to resolve their capacity needs for at least a decade; however, within just 2 years, the jail had surpassed capacity again. Despite increasing bed space by remodeling and by adding a trailer jail annex, the continuation of bad policies, such as criminalizing poverty by rounding up and arresting unhoused people, led to what a 2017 needs assessment called “unsustainable” jail growth, which forced another $150 million 1,252-bed expansion in 2020.

Similarly, Lubbock County, Texas, spent $94.5 million in taxpayer bonds building a new 1,512-bed jail, which opened in 2010. Though intended to meet their capacity needs well into the future, jail population growth has persisted, leading county officials to spend a million dollars of the county’s budget incarcerating people in other counties. But there are other obvious solutions to Lubbock’s over-incarceration problem. Lubbock County mostly uses its jail to house people who haven’t been convicted of a crime; in January of 2024, 76% of the jail’s population were people being held pretrial, and fully one tenth of the people in the jail were being held pretrial for a misdemeanor. Pretrial detention practices play a huge part in the county’s perpetual capacity problems. County officials have nevertheless repeatedly looked to build their way out of these issues instead of implementing sustainable policy changes like ending pretrial detention for misdemeanors and reexamining alternatives to cash bond. As a result, Lubbock’s sheriff recently proposed a 996-bed expansion projected to cost taxpayers another $464 million, bringing the total to more than half a billion dollars, with no substantial policy change in sight.

While capacity arguments are often used to justify jail expansion, the truth is counties cannot build their way out of capacity issues without addressing the policies that created them in the first place. Despite claims that jail construction is driven by need, in many instances, the reverse is actually true. As Greene County’s assessment noted, “The dramatic increase in bookings is probably due [in part to] the increased availability of beds with the opening of the new jail.” Simply put, if you build it, they will fill it.

Box office bombs (the “contemporary” argument)

Often, the promise of a shiny new jail with updated facilities leads to over-budget projects that sap taxpayer money far into the future. These projects, focused on building jails with “all the bells and whistles,” often collide with soaring construction costs. This can sometimes lead to facilities that are too costly to staff and maintain or even too costly to complete. As a result, projects can wind up half-finished or sitting empty for years at taxpayer expense.

Despite voters rejecting an $88 million bond initiative to fund a new jail in 2004, by 2008, Thurston County, Washington, accepted a bid for “the cutting-edge $45 million Accountability and Restitution Center (ARC) jail complex,” a building some have referred to as the “Taj Mahal design of Jail, Law and Justice Centers.” Finished in 2010, the jail sat empty for 6 years, costing the taxpayers roughly $430,000 annually, largely because the county did not budget for the additional staff needed to run it. Just three years later, the county would approve a $19-25 million jail expansion featuring a 40-bed “‘flex unit’ with cells that could be used in different ways as needs change” plus a shell for future expansion.

In Wayne County, Michigan, construction began on a “state-of-the-art” $300 million, 2,192-bed jail in 2011. The design included innovations that some claimed would bolster security, largely by further restricting movement. By 2013, the project was already $91 million over budget due to ballooning construction costs, forcing it to be abandoned and leading to the indictment of three Wayne County Officials for lying about the project’s cost. The jail sat incomplete and empty for years, costing the taxpayers around $1 million per month just to maintain.

Though not a jail, Thomson Prison in Illinois shares a similar story. Built in 2001 for $145 million, this new high-tech maximum-security prison sat empty at the taxpayers’ expense for 11 years due to state budgetary restraints impacting the ability to staff it before finally being sold to the federal government4 in 2012.

As these examples illustrate, officials often claim that a new “modern” jail will solve a jurisdiction’s problems. While the drumbeat here is safety or security, these projects almost invariably also include millions for expanding bed space to incarcerate more people. Moreover, while huge amounts of money are poured into building bigger, better, and newer buildings, the massive costs associated with staffing and operating these monstrosities, and the fact that existing prisons and jails around the country are dangerously understaffed as it is, can result in costly projects that can’t be staffed even if they are completed. These monuments to incarceration can sit empty for years, draining the public coffer.

Promises, promises (the “compassionate” argument)

Increasingly, counties cite the need to be compliant with ADA requirements or the idea that jails should be providers of mental health services or substance use treatment as reasons to expand. This “compassionate” argument repackages incarceration as care and can mean taking money away from health services in the community. This is particularly problematic when jails fail to deliver on these promises, as they regularly do.

McLean County, Illinois’ 2015 jail needs assessment called for more space for housing people with mental health needs. In response, the county spent $43.5 million to build a new jail with a “Community Crisis Stabilization Facility” in 2017. A few short years later, however, people with mental health concerns are once again being held in the booking area (a practice the new jail was supposed to end) and are being held at jails outside of the county, unable to “benefit” from McLean’s new $43.5 million carceral alternative to community-based crisis intervention.

Broome County, New York, similarly promised to provide better medical care as part of its argument to secure $6.8 million to expand its jail in 2015. 5 But once the new jail was built, there was little effort to deliver on this promise: Broome County maintained the same dubious medical provider, Correctional Medical Care (CMC), that had been sued multiple times for medical negligence 6 from 2010 all the way until 2022. Many of these claims involved jail deaths. CMC’s practices were so bad that the New York State Commission on Corrections’ Medical Review Board chastised the company for “egregious lapses in medical care” in their 2018 “Problematic Jails” report. More incarcerated people died in the five years after ground broke on jail expansion than in the five years before, during CMC’s contract tenure with Broome County. 7

People interested in improving the lives of incarcerated people are often swayed by “compassionate” arguments. But they should never lose sight of the fact that incarceration itself is inherently harmful to physical and mental health, leaving many with a PTSD-like condition called Post-Incarceration Syndrome, which can even trigger drug use. At best, jail as a place of treatment is ineffectual. At worst, these bad policies drain funding from community-based support systems that can address challenges before a crisis results in incarceration. Jail is a place of trauma, not healing.

Change — The other “C”

While these three C’s are often used to argue for jail construction, advocates can and should confront their local officials with real solutions for reducing jail populations and providing mental health and substance use care.

- Reduce pretrial detention: Nationwide, 83% of people in jails have not been convicted of a crime. One of the most effective ways to bring down jail populations is to reform the way court systems treat people accused of crimes. Policies ranging from citation and release to ending cash-based pretrial detention can massively reduce jail capacity needs without raising taxes, incarcerating more people, or jeopardizing public safety.

- Focus on community-based care: Jail was never intended to be a provider of social services. As the Justice LA Coalition successfully argued in opposition to a $2 billion mental health-focused jail in 2019, true compassion comes not in the trauma of a cell but in funding for community-based care and support for those with addiction issues or mental health needs.

- Reduce total jail capacity: If jail construction absolutely cannot be avoided (as in the case of places under court orders to update or build a new facility), it should be contained so that it does not expand the capacity of the current jail to incarcerate or invest in new carceral technologies. If there’s no way to avoid building a new jail, advocates can at least work on making sure the new one doesn’t expand the number of people behind bars.

Conclusion

Though common arguments in favor of jail expansion are compelling at first glance, investing in jail construction is not a solution to social problems but rather doubling down on policies that caused these problems to begin with that can burden a community for decades to come. Ultimately, many of these arguments can be answered by asking pointed questions, revising policies, and being responsive to the community’s actual needs.

Footnotes

-

Congress passed the American Relief Plan Act (ARPA) in 2021. Though this act allotted $350B to help state and local governments recover from the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, many jurisdictions have used this money to expand and build new jails and prisons. ↩

-

As Vera notes in their exhaustive 2019 report, which identifies similar arguments and touches on many of the issues here, jurisdictions may also be motivated by “financial incentives.” This can mean increasing jail size to keep from renting bed space from other places or even increasing their ability to rent out space themselves as an extra revenue stream. We did not include it among our three main arguments (though it could certainly be considered a fourth “C” — for “cash”) because this is not typically the main argument for a new facility, but rather an additional supporting argument. ↩

-

Needs assessments are studies that look at current jail populations and attempt to forecast future jail populations. ↩

-

After the sale, Thomson Prison became one of the most violent and deadly prisons under the auspices of the BOP, with a culture of abuse so ingrained that guards tried to have a warden assassinated when he attempted to intervene. ↩

-

Broome County also relied upon a capacity argument, citing a 2014 needs assessment which projected 710 beds to be needed by 2028. However, by 2023, with the sole exception of Lewis County, which increased from 31 to 32 people, every single county across New York state saw a decrease in its average daily jail population. Broome County itself saw the jail population decrease by more than 34% over that span, illustrating how places often overestimate future capacity needs and underestimate the potential of changing policies to decrease jail populations. ↩

-

As well as for allegedly forcing its employees to falsify incarcerated people’s medical records. ↩

-

CMC held Broome County’s contract to provide medical services to the jail from 2010 until 2022. There were 4 custody deaths in Broome County jail between 2011 and April of 2015, when ground broke on the county’s jail expansion project. From May 2015 until 2020, there were reported 5 custody deaths at Broome County Jail. ↩