Can you help us sustain this work?

Thank you,

Peter Wagner, Executive Director Donate

Rigging the jury: How each state reduces jury diversity by excluding people with criminal records

by Ginger Jackson-Gleich

February 18, 2021

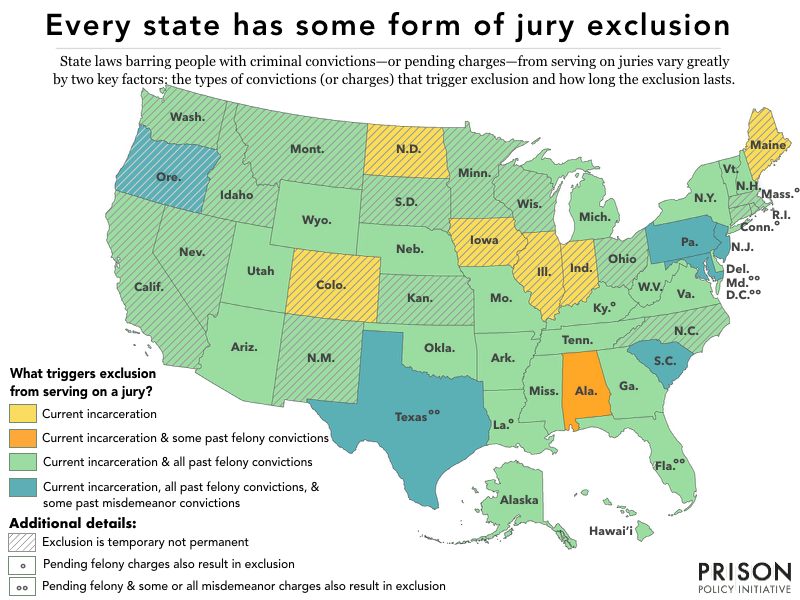

In courthouses throughout the country, defendants are routinely denied the promise of a "jury of their peers," thanks to a lack of racial diversity in jury boxes.1 One major reason for this lack of diversity is the constellation of laws prohibiting people convicted (or sometimes simply accused) of crimes from serving on juries.2 These laws bar more than twenty million people from jury service, reduce jury diversity by disproportionately excluding Black and Latinx people, and actually cause juries to deliberate less effectively. Such exclusionary practices exist in every state and often ban people from jury service forever.

Jury exclusion laws hinder jury diversity

As we have chronicled extensively, the criminal justice system disproportionately targets Black people and Latinx people—so when states bar people with criminal convictions from jury service, they disproportionately exclude individuals from these groups. Of the approximately 19 million Americans with felony convictions in 2010, an estimated 36% (nearly 7 million people) were Black, despite the fact that Black people comprise 13% of the U.S. population. Although data on the number of Latinx people with felony convictions is difficult to find (because information about Latinx heritage has not always been collected or reported accurately within the criminal justice system), we do know that Hispanic people are more likely to be incarcerated than non-Hispanic whites and are overrepresented at numerous stages of the criminal justice process. It stands to reason, then, that Latinx populations are also disproportionately likely to have felony convictions.

As a result, jury exclusion statutes contribute to a lack of jury diversity across the country. A 2011 study found that in one county in Georgia, 34% of Black adults—and 63% of Black men—were excluded from juries because of criminal convictions. In New York State, approximately 33% of Black men are excluded from the jury pool because of the state’s felony disqualification law. Nationwide, approximately one-third of Black men have a felony conviction; thus, in most places, many Black jurors (and many Black male jurors in particular) are barred by exclusion statutes long before any prosecutor can strike them in the courtroom.

Jury diversity makes juries more effective

Not only does jury diversity underpin the constitutional guarantee of a fair trial and ensure that juries represent the “the voice of the community,” research shows that diverse juries actually do a better job. A 2004 study found that diverse groups “deliberated longer and considered a wider range of information than did homogeneous groups.” In fact, simply being part of a diverse group seems to make people better jurors; for example, when white people were members of racially mixed juries, they “raised more case facts, made fewer factual errors, and were more amenable to discussion of race-related issues.” Another study found that people on racially mixed juries “are more likely to respect different racial perspectives and to confront their own prejudice and stereotypes when such beliefs are recognized and addressed during deliberations.” In addition, the verdicts that diverse juries render are more likely to be viewed as legitimate by the public.

In some states, even misdemeanors can disqualify people from jury service

While the laws barring people with criminal convictions from jury service are often referred to as “felony exclusion laws,” in some states (and in federal courts), people with misdemeanor convictions can also be subject to exclusion. Texas, for example, specifically excludes from juries people who have been convicted of misdemeanor theft. Maryland, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina exclude people who have been convicted of any crime punishable by more than one year of incarceration, which includes certain misdemeanors in those states. Oregon excludes people convicted of certain misdemeanors for five years post-conviction. And several states and Washington, D.C. exclude people currently facing misdemeanor charges. This is in addition to states like Montana, Tennessee, and West Virginia that disqualify people only for those rare misdemeanors related to violating civic or public duties (a level of detail not reflected in the chart below).3

50 States: What triggers exclusion from serving on a jury?

| Current incarceration | Current incarceration & some past felony convictions | Current incarceration & all past felony convictions | Current incarceration, all past felony convictions, & some past misdemeanor convictions |

|---|---|---|---|

| No legal exclusion, but incarcerated jurors excused

Maine No exclusion after incarceration ends Indiana North Dakota No exclusion after incarceration ends (although attorneys may request dismissal by the court) Colorado Illinois Iowa |

Forever

Alabama |

Forever

Arizona Arkansas Delaware Florida Georgia Hawaii Kentucky Louisiana Michigan Mississippi Missouri Nebraska New Hampshire New York Oklahoma Tennessee Utah Vermont Virginia West Virginia Wyoming For a fixed period of time Connecticut District of Columbia Kansas Massachusetts Nevada Until sentence completed (including parole and probation) Alaska California (certain offenses lead to permanent exclusion) Idaho Minnesota Montana New Mexico North Carolina Ohio Rhode Island South Dakota Washington Wisconsin |

Forever

Maryland New Jersey Pennsylvania South Carolina Texas For a fixed period of time Oregon |

| Pending criminal charges also result in exclusion

Connecticut, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Massachusetts also exclude anyone currently facing felony charges. Florida, Maryland, Texas, and D.C. also exclude anyone currently facing felony charges or facing (some or all) misdemeanor charges. | |||

Recommendations for reform

Reduce the scope of exclusion laws. The good news is that change is possible. California recently passed legislation—championed by public defenders—largely ending the permanent exclusion of people with felony convictions. In most contexts, Californians may now serve on juries upon completion of felony sentences, once probation and parole have ended. Prior to the change, the state’s felony exclusion law prohibited 30 percent of California’s Black male residents from serving on juries. While California’s jury exclusion law is still more punitive than the laws in many states, this recent change shows that reform is possible. Other states can and should follow suit.

At the same time, as Professor James Binnall insightfully observes, once reform legislation is passed, it remains critically important to ensure full implementation of the law by restoring formerly excluded people to jury rolls. This process has met with mixed success in California, where months after the law went into effect, 22 of 58 counties were still providing incorrect or misleading information about eligibility to the public. (Professor Binnall’s new book on jury exclusion offers detailed analysis of the impact of these exclusionary statutes, as well as a comprehensive takedown of the justifications usually offered in their defense; we also recommend Professor Anna Roberts' article Casual Ostracism for anyone looking for a compelling orientation to the issue of jury exclusion laws.)

Decriminalize and decarcerate. Of course, a more sweeping way to address jury exclusion laws would be to reduce the number of people with criminal convictions generally. This approach would entail criminalizing fewer behaviors, incarcerating fewer people, and penalizing criminal activity less harshly. Permitting 20 million people with felony convictions to serve on juries would be a powerful step toward a fairer and more effective legal system, but a far more holistic approach would be reducing the number of people who have criminal convictions in the first place.

Address other obstacles to jury diversity. Thanks to the efforts of advocates, many states are also taking steps to address other early-stage roadblocks to jury diversity. For example, states that draw jury pools exclusively from voting rolls inherently exclude anyone whose felony conviction prevents them from voting, even if the state technically allows them to serve on juries. To avoid this problem, states can draw potential jurors from additional sources, such as state tax records and DMV records. Some jurisdictions have begun to conduct more frequent address checks to decrease rates of undeliverable jury notices, or to require that a replacement summons be sent to the same zip code from which an undeliverable notice was returned. And Louisiana recently increased jury compensation, a small change that the American Bar Association notes makes it possible for “a broader segment of the population to serve.”

No matter how it’s done, reforming the nation’s many jury exclusions laws (and the many other barriers to jury diversity) will be a long, steep road, and the challenges will vary greatly from state to state. However, successful reform will bring millions of Americans back into the jury box and help to truly realize the promise of a fair trial by jury.

Appendix: How do states exclude people with criminal charges and/or convictions from jury service?

This table indicates which jurisdictions exclude people from jury service on the basis of criminal charges or convictions, how long such exclusion lasts, and which statutes set forth the law. The explanatory notes and footnotes here seek to clarify more complex issues that were not addressed in the table above. Here, too, the focus of this table is trial (or "petit") juries, as opposed to grand juries.

As noted in the table above, many states have rights restoration procedures (such as executive pardons, expungement, etc.) that can restore rights to individuals who would otherwise be barred from jury service; relief via such processes is generally rare and therefore mostly not included here. We also note that exclusion from jury service is often a penalty for crimes specifically related to juror misconduct or abuse of public office; however, we have generally not delved into that level of complexity here, particularly because such crimes are rare.

As stated previously, in addition to conducting our own legal analysis and speaking with court staff in numerous states, we consulted several great resources during the research stage of this project. In particular, we recommend the Restoration of Rights Project's 50-State Comparison, the National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction, and this 2004 article by Professor Brian Kalt. Professor Kalt's piece discusses other state-level specifics, such as whether convictions from other jurisdictions lead to exclusion, how rights restoration processes work, how errors related to criminal records are resolved, and distinctions between rules for civil/criminal jury service or petit/grand juries. State rules also vary in whether restitution payments must be completed before rights can be restored.

As always, we welcome your input if you have corrections to any of the information presented.

| State | Which crimes trigger jury pool exclusion? | Upon conviction, how long does jury pool exclusion last? | Statutes and notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Some felonies4 | Forever | See Ala. Code § 12-16-60, and the Secretary of State's list of crimes involving moral turpitude. In addition, all felonies are a basis for challenge, even those not triggering exclusion from the pool. |

| Alaska | All felonies | Until sentence completed (incl. probation and parole). | See Alaska Stat. §§ 09.20.020, 12.55.185. |

| Arizona | All felonies | Forever, upon second felony.5 | See Ariz. Rev. Stat. §§ 13-904, 13-907. |

| Arkansas | All felonies | Forever | See Ark. Code Ann. § 16-31-102. |

| California | All felonies6 | Until sentence completed (incl. probation and parole). However, convictions requiring sex offender registration result in permanent disqualification. | See Cal. Const. art. VII, § 8; Cal. Civ. Proc. § 203. |

| Colorado | None | N/A | There is no automatic exclusion once incarceration ends. However, in the courtroom, the parties may consider the fact of a felony conviction in "determining whether to keep a person on the jury." See Colo. Rev. Stat. § 13-71-105. |

| Connecticut | All felonies | Limited period (while accused, while incarcerated, or 7 years post-conviction). | See Conn. Gen. Stat. § 51-217. In addition, a juror who engages in a second prohibited conversation while on jury, can be banned for life. See Conn. Gen. Stat. § 51-245. |

| Delaware | All felonies | Forever | See Del. Code Ann. tit. 10, § 4509. |

| D.C. | All felonies and all misdemeanors | For 1 year after the completion of incarceration, probation, supervised release, or parole, following conviction of a felony. People are also excluded while accused of either a felony or a misdemeanor. | See D.C. Code. § 11-1906. |

| Florida | All felonies and all misdemeanors | Forever upon conviction of a felony. People are also excluded while accused of either a felony or misdemeanor.7 | See Fla. Stat. § 40.013. |

| Georgia | All felonies | Forever | See Ga. Code Ann. § 15-12-40. |

| Hawaii | All felonies | Forever | See Haw. Rev. Stat. § 612-4. |

| Idaho | All felonies | Until end of sentence (incl. probation and parole), if a term of incarceration is served. | See Idaho Code §§ 2-209, 18-310. |

| Illinois | None | N/A | There is no automatic exclusion once incarceration ends. However, in the courtroom, a prior felony conviction can be a basis for a challenge. |

| Indiana | All felonies | Until released from custody | See Ind. Code Ann. §§ 33-28-5-18; 3-7-13-4. |

| Iowa | None | N/A | There is no automatic exclusion once incarceration ends. However, in the courtroom, a prior felony conviction can be a basis for a challenge. See Iowa R. Civ. P. 1.915, 2.18. |

| Kansas | All felonies | For 10 years after conviction or upon completion of sentence (incl. probation and parole), whichever is longer. | See Kan. Stat. §§ 43-158, 21-6613. |

| Kentucky | All felonies | Forever upon conviction, and while accused of a felony. | See Ky. Rev. Stat. § 29A.080. |

| Louisiana | All felonies | Forever upon conviction, and while accused of a felony. | See La. Code Crim. Proc. art. 401. |

| Maine | No felonies | N/A | While Maine does not technically bar those incarcerated from serving on juries, it appears that the common practice is to excuse them. |

| Maryland | All felonies and all misdemeanors | Forever upon conviction of a felony. People are also excluded upon conviction of some misdemeanors,8 and while accused of either a felony or any misdemeanor punishable by more than 1 year of imprisonment. | See Md. Code Ann., Cts. & Jud. Proc. § 8-103. |

| Massachusetts | All felonies | Limited period (while accused, while incarcerated, or 7 years post-conviction)9 | See Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 234A, § 4. |

| Michigan | All felonies | Forever | See Mich. Comp. Laws § 600.1307a. |

| Minnesota | All felonies | Until sentence completed (incl. probation and parole) | See Minn. Const. art. VII, § 1; Minn. Stat. § 609.165. See also this court guidance. |

| Mississippi | All felonies | Forever | See Miss. Code Ann. §§ 13-5-1, 1-3-19. |

| Missouri | All felonies | Forever | See Mo. Rev. Stat. §§ 494.425; 561.026. |

| Montana | All felonies10 | Until sentence completed (incl. probation and parole) | See Mont. Code Ann. §§ 3-15-303; 46-18-801. |

| Nebraska | All felonies | Forever11 | See Neb. Rev. Stat. §§ 29-112, 29-112.01, 25-1650. |

| Nevada | All felonies | Excluded from civil juries until sentence completed. Excluded from criminal juries for 6 years after sentence completed. | See Nev. Rev. Stat. §§ 176A.850, 213.155. |

| New Hampshire | All felonies | Forever | See N.H. Rev. Stat. § 500-A:7-a. |

| New Jersey | All felonies and some misdemeanors12 | Forever | See N.J. Rev. Stat. § 2B:20-1. |

| New Mexico | All felonies | Until sentence completed (incl. probation and parole) | See N.M. Stat. Ann. § 38-5-1. |

| New York | All felonies | Forever | See N.Y. Jud. Law § 510. |

| North Carolina | All felonies | Until sentence completed (incl. probation and parole) | See N.C. Gen. Stat. §§ 9-3, 13-1. |

| North Dakota | All felonies | While incarcerated13 | See N.D. Cent. Code §§ 12.1-33-01, 12.1-33-03, 27-09.1-08. |

| Ohio | All felonies | Until sentence completed (incl. probation and parole) | See Ohio Rev. Code §§ 2313.17, 2945.25, 2961.01, 2967.16. |

| Oklahoma | All felonies | Forever | See Okla. Stat. tit. 38, § 28, tit. 22, § 658. |

| Oregon | All felonies and some misdemeanors14 | Excluded while incarcerated, and for 15 years following a felony conviction. Excluded from criminal juries for 5 years following certain misdemeanor convictions. | See Or. Const. art. I, S 45; Or. Rev. Stat. §§ 137.281, 10.030. |

| Pennsylvania | All felonies and some misdemeanors15 | Forever | See 42 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 4502. |

| Rhode Island | All felonies | Until sentence completed (incl. probation and parole) | See R.I. Gen. Laws § 9-9-1.1. |

| South Carolina | All felonies and some misdemeanors16 | Forever | See S.C. Code Ann. § 14-7-810. |

| South Dakota | All felonies | Until sentence completed (incl. probation and parole). | See S.D. Codified Laws §§ 16-13-10, 23A-27-35. |

| Tennessee | All felonies17 | Forever | See Tenn. Code Ann. §§ 22-1-102, 40-29-101. |

| Texas | All felonies and misdemeanor theft | Forever upon conviction of any felony or of misdemeanor theft. People are also excluded while charged with any felony or with misdemeanor theft. | See Tex. Gov't Code § 62.102. |

| Utah | All felonies | Forever | See Utah Code Ann. § 78B-1-105. |

| Vermont | All felonies | Forever, if a term of incarceration is served. | See Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 12, § 64; tit. 4, § 962. |

| Virginia | All felonies | Forever18 | See Va. Code Ann. § 8.01-338. |

| Washington | All felonies | Until sentence completed (incl. probation, parole, and any financial obligations) | See Wash. Rev. Code §§ 2.36.070, 9.94A.637. |

| West Virginia | All felonies19 | Forever | See W. Va. Code § 52-1-8; W. Va. Const. art. IV, § 1. |

| Wisconsin | All felonies | Until sentence completed (incl. probation and parole) | See Wis. Stat. §§ 756.02, 304.078. |

| Wyoming | All felonies | Forever22 | See Wyo. Stat. Ann. §§ 6-10-106, 1-11-102. |

| Federal | All felonies20 and some misdemeanors21 | Forever upon conviction of a felony or a misdemeanor punishable by more than one year of imprisonment. People are also excluded while such charges are pending. | See 28 U.S.C. § 1865. |

Acknowledgments

Ginger and the Prison Policy Initiative thank the numerous legal experts who provided insight during the preparation of this report, particularly Jennifer Sellitti at the New Jersey State Office of the Public Defender, Margaret Love at the Collateral Consequences Resource Center, and numerous staff at the state courts of Mississippi, New Jersey, North Dakota, South Carolina, and South Dakota. The author also thanks Katie Rose Quandt, Peter Wagner, Emily Widra, Wanda Bertram, Wendy Sawyer, and Tiana Herring for their editorial guidance and technical support.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. Alongside reports like this that help the public engage in criminal justice reform, the organization leads the nation's fight to keep the prison system from exerting undue influence on the political process (known as prison gerrymandering) and plays a leading role in protecting the families of incarcerated people from the predatory prison and jail telephone industry and the video visitation industry.

About the Author

Ginger Jackson-Gleich is Policy Counsel at the Prison Policy Initiative. She previously wrote about the ways that mass incarceration undermines democracy in her major report Eligible but Excluded: A guide to removing the barriers to jail voting. Ginger's focus at the Prison Policy Initiative is on our campaign to end prison gerrymandering. She was involved in criminal justice reform for 15 years prior to joining the Prison Policy Initiative.

Footnotes

For an overview of the lack of racial diversity in juries, see Lack of Jury Diversity: A National Problem with Individual Consequences from the American Bar Association. ↩

Racially non-diverse juries are, of course, caused by many factors, including the well-documented racism that infects the final stages of jury selection, when prosecutors and defense attorneys interview and eliminate potential jurors. For a quick overview of the “legal loophole” that permits such discrimination, see this 8-minute video from Vox. ↩

For more about the staggering number of collateral consequences that can be triggered by a misdemeanor conviction, check out Misdemeanorland by Professor Issa Kohler-Hausmann and Punishment Without Crime by Professor Alexandra Natapoff. ↩

Those involving moral turpitude. ↩

For first-time felonies, exclusion lasts until sentence completed, including any financial restitution being discharged. ↩

And misdemeanor malfeasance in office. ↩

In the course of our research, several court employees asserted that people convicted of certain misdemeanors are also excluded from juries under Florida law. However, both legal precedent and widespread county practice indicate that people with misdemeanor convictions do not lose the right to serve on juries. While there may be some conflicting information on this topic, our conclusion is that misdemeanor convictions are not disqualifying. ↩

Those punishable by more than 1 year of imprisonment. ↩

Rights are restored automatically when someone becomes legally eligible. ↩

And misdemeanor malfeasance in office. ↩

Someone who receives a noncustodial sentence upon conviction of a felony regains jury eligibility after completion of their sentence. ↩

New Jersey classifies crimes differently from other states; thus, the category of crimes that are disqualifying in New Jersey (those punishable by more than 1 year of imprisonment, referred to as "indictable offenses"), encompasses what would be classified as more serious misdemeanors in other places. ↩

North Dakota law also contemplates that a "conviction of a criminal offense…[can] by special provision of law" disqualify a prospective juror. However, attorneys at the N.D. Supreme Court informed us that they were aware of no such provisions currently in operation. ↩

Involving violence or dishonesty. ↩

If punishable by more than one year of imprisonment. ↩

If punishable by more than one year of imprisonment. ↩

And misdemeanor perjury or subornation of perjury. ↩

Since 2013, Virginia's governors have used their executive powers to restore civil rights to hundreds of thousands of Virginians with felony convictions. Nonetheless, the underlying law in Virginia (which imposes permanent jury exclusion upon people convicted of felonies) remains the same. ↩

And misdemeanor perjury, false swearing, and bribery. ↩

Whether proceeding is in state or federal court. ↩

If state or federal crime is punishable by more than one year of imprisonment (in some states this will include misdemeanors). ↩

Someone convicted of a nonviolent felony (and without prior felony convictions) will regain jury eligibility upon application to the state board of parole after completion of sentence. See Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 7-13-105. ↩