Can you help us sustain this work?

Thank you,

Peter Wagner, Executive Director Donate

Contending with Carveouts:

How and Why to Resist Charge-Based Exclusions in Reforms

- Sections

- What is a carveout?

- Why are fentanyl carveouts so harmful?

- Carveouts are ubiquitous but not inevitable

- Carveouts are stifling progress

- Responses to arguments in favor of carveouts

Criminal legal system reforms are being introduced at a rapid pace across the United States, often with the stated goal of reducing our extreme prison and jail populations. Too often, however, these reforms are handicapped because they exclude large categories of people impacted by the criminal legal system. These “carveouts” generally exclude people charged with or convicted of violent, sex-related, or other serious charges. This is sometimes referred to as focusing on the “non, non, nons” — nonviolent, non-sexual, and non-serious charges. “Serious” charges often include drug crimes that involve specific controlled substances, like fentanyl or methamphetamines. Too often, policymakers believe that these carveouts are politically necessary in order to pass legislation, or believe that they are actually good policy.

Some criminal legal system reformers make the mistake of assuming that carveouts are an unavoidable or necessary part of all criminal legal reform. But the reality is that criminal legal system reform will never achieve its goals if we continue to focus only on non-violent, non-sexual, and non-serious charges. Carveouts dramatically lessen the impact of criminal legal system reforms, and create a more difficult political landscape for later reform.

Carveouts are common, but not inevitable. Below, the Prison Policy Initiative has gathered a set of resources for advocates and policymakers to understand the problems posed by carveouts and equip them with arguments to make sure that criminal legal reform can be for everyone, not just for a small subset of impacted people.

What is a carveout?

For the purposes of this guide, we define carveouts as any policy that excludes people from criminal legal system reforms based on what they are charged with or convicted of.1 You can often spot these carveout clauses because they begin with words like “other than” or “except.” Sometimes they include a specific list of charges that are carved out from the reform; other times, they use broad language like “nonviolent” charges to describe the people who the reform applies to, implicitly carving out people with violent charges.

For example, in 2017, Louisiana made changes to its probation system, including allowing “earned compliance credits” so that people could shorten their probation terms by completing requirements. Even though credits would only be given if someone was compliant on probation, Louisiana entirely carved out anyone convicted of a crime of violence or a sex-related offense:

Every defendant on felony probation pursuant to Article 893 for an offense other than a crime of violence as defined in R.S. 14:2(B) or a sex offense as defined in R.S. 15:541 shall earn a diminution of probation term, to be known as “earned compliance credits”, by good behavior. The amount of diminution of probation term allowed under this Article shall be at the rate of thirty days for every full calendar month on probation.

As another example, in 2019, Missouri created a program of veterans treatment courts. To be eligible for this program, Missouri required that the alleged crime be “nonviolent, nonsexual, does not involve a child victim or possession of an unlawful weapon.” This carveout was completely unnecessary, given that prosecutors have full discretion over who entered the courts, and were under no obligation to accept any particular person into their veterans treatment courts.

Not all carveouts concern violent or sex-related offenses. For example, despite the progress made in recent years toward decriminalizing drug possession, legislators are increasingly treating fentanyl possession as an exception, advancing bills that lower the threshold for felony prosecution and/or increase penalties.

Carveouts are ubiquitous — but not inevitable

Almost all major criminal legal system reforms in the last 20 years have excluded people charged with or convicted of violent or sex-related offenses.

Criminal legal system reforms that exclude people based on charge

We found states that single out violent offenses:

Block access to alternatives to incarceration |

Withhold relief from collateral consequences |

Restrict opportunities for release |

Impose two or more of these restrictions |

No examples found |

This interactive map originally appeared in our 2020 report, Reforms Without Results: Why states should stop excluding violent offenses from criminal justice reforms. States engaging in criminal legal reform passed at least 75 pieces of legislation between 2010 and 2019 that exclude the single largest part of their prison and jail populations — people convicted of violent offenses. See that report’s appendix for a list of all examples shown here.

Often, these carveouts apply to programs that are already discretionary, as in the Missouri veterans treatment courts example. These kinds of carveouts are particularly irrational. Discretionary programs already allow decision makers to exclude people from programs based on a variety of factors, including, often, the seriousness or facts of the crime a person is charged with. To carve out all violent, sex, or serious charges from discretionary programs actually removes discretion from decisionmakers, rather than empowering them to make nuanced decisions.

Carveouts are not, however, a foregone conclusion. Limited progress has been made avoiding carveouts in some programs in some states. Some recent examples are:

- In 2023, New Mexico passed a law abolishing life without parole sentences for children, and making all people previously sentenced to life without parole as children eligible for parole. Although people charged with murder must serve more of their prison sentence before being eligible for parole, everyone sentenced to life in prison as a child is eventually eligible for parole.

- In 2021, Illinois passed the Joe Coleman Medical Release Act, creating a medical release procedure that is available to all people in prison who are terminally ill or medically incapacitated, regardless of their crime of conviction or their original sentence.

- The District of Columbia created a resentencing process in 2019 for people under 18 at the time of the commission of their offense and in 2021 expanded this process to include people who were under 25; people are eligible regardless of the crime they were convicted of.

- Both Washington state in 2020 and Illinois in 2021 created resentencing processes that allow prosecutors to motion for the resentencing of any person in custody, regardless of their crime of conviction.

Carveouts are stifling progress on ending mass incarceration

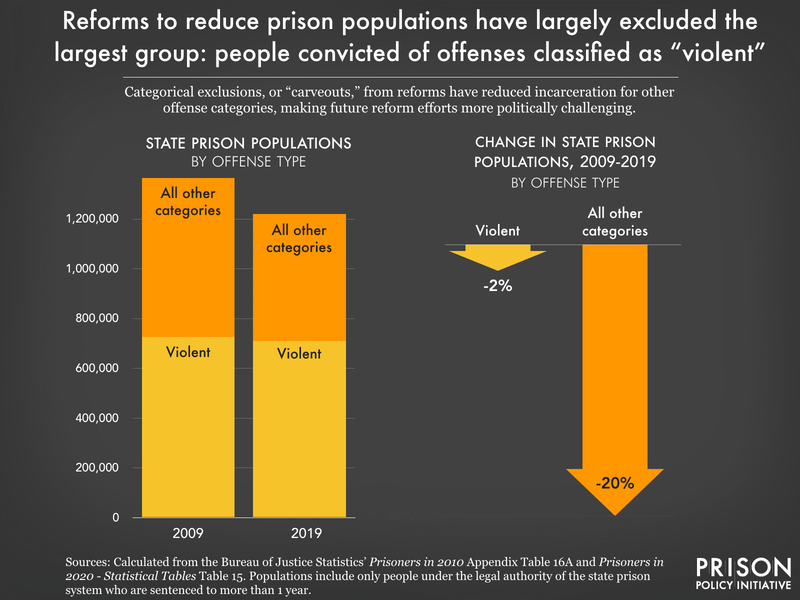

We cannot end mass incarceration if reforms only target “non, non nons.” It is a common misconception that most people in prison are there for drug or nonviolent crime. In fact, only 1 in 5 people in prison is locked up for a drug offense. About two-thirds of people in state prisons are incarcerated for a “violent” crime,2 including 15% who are incarcerated for murder. The proportion of the prison population that is incarcerated for violent crimes has risen over time, in part because reforms have been targeted exclusively at “non, non, nons.”

Even if we released every person charged with a drug, public order, and property crime from prison, we would still not achieve a 50% reduction in the U.S. prison population. To achieve substantial reductions, reforms have to facilitate release for large numbers of people convicted of violent crimes.

Responses to common arguments in favor of carveouts

Policymakers use various arguments to justify the existence of carveouts in their legislation. Below, we‘ve paired some common arguments in favor of carveouts with counterarguments and data and reports that support them.

Argument #1: “We have to start reforms with nonviolent charges, and we’ll “come back” for more serious charges later”

It’s common to hear policymakers argue that carveouts are a necessary part of criminal legal system reform, and that narrow laws that target only the “non, non, nons” are just a “first step” towards larger reform. President Barack Obama, for example, acknowledged that large-scale prison population reductions could not occur without including people with violent convictions in reforms, yet still argued for a carveout approach:

Can we, in fact, significantly reduce the prison population if we’re only focusing on non-violent offenses where part of the reason that in some countries — in Europe, for example — they have a lower incarceration rate because they also don’t sentence violent offenders for such long periods of time. I think it’s smart for us to start the debate around non-violent drug offenders. You are right that that’s not going to suddenly halve our incarceration rate, but if we get that — if we do that right — then that becomes the foundation upon which the public has confidence in potentially taking a future step and looking at sentencing changes down the road.

Certainly, it is often true that starting with the “low hanging fruit” of non-violent, non-sexual, and non-serious charges is politically expedient. But it is not good policy. There is no reason to believe that starting reform with carveouts will ever lead to “coming back” to address those left out of initial reforms — and indeed, decades of legislation with carveouts has not lead to a wave of legislation “coming back” to address the majority of people in prison. Instead, carveouts make the political landscape for future reform more difficult, in part because the logic of carveouts reinforces unhelpful narratives about people in prison.

Counterargument:Carveouts reinforce the flawed logic of mass incarceration

All criminal legal system reform involves coming face-to-face with our society’s strong biases against people who have been charged with and convicted of crimes. Facing these societal biases requires political courage and clear, forceful responses to misinformation and fearmongering. Carveouts do nothing to challenge or undermine biases against incarcerated people. In fact, as Critical Resistance, a prison abolitionist grassroots organization, has expressed, carveouts “entrench the idea that anybody ‘deserves’ or ‘needs’ to be locked up” and “reinscribe the idea that some people are ‘risks’ to society and others ‘deserve another chance’ strengthening logics of punishment without engaging the context of how harms happen.” In other words, the rationale for carveouts rests on the same foundations as mass incarceration itself.

Counterargument:Carveouts make later reform harder, not easier

If we intend to eventually make a certain reform available to people regardless of their charge, the best approach is to make as many people as possible eligible for the reform at the same time. Reforming in stages, starting with the people society is least biased against (those with lower level offenses) increases the likelihood that people with serious charges will be forever left behind.

To illustrate this problem, imagine a state starts creating a discretionary parole system by extending parole to people with any charge except murder. The bill faces opposition, but in part because it will benefit people with nonviolent convictions, whom legislators are more sympathetic to, the bill passes. A few years later, a second reform tries to extend parole to people who were not originally included in the first bill. The second reform will have the heavy lift of convincing legislators to pass a bill that will benefit only people accused of murder — the people against whom there is the most bias in the general public. Rather than “building a foundation” for later reform, carveouts can make later reform harder.

Argument #2:“Victims of crime want people with violent charges excluded from reform”

Policymakers sometimes believe that victims of crime and the groups that represent them want people with violent charges to remain behind bars forever. In actuality, surveys of victims show that they are interested in investments in alternatives to incarceration, not long prison sentences. Harsh sentences don’t deter violent crime, and national survey data shows that many victims believe that longer sentences lead to more public safety risk, not less.

In addition, although people tend to view those convicted of violent crime and victims of violent crime as two distinct groups of people, people in prison are in fact highly likely to have experienced or been exposed to violence themselves:

- A national survey of youth in custody showed that 67% had personally seen someone severely injured or killed.

- More than 1/3 of people entering Arkansas prisons reported having been shot or stabbed.

Crime victims are a diverse group of people with many different opinions about approaches to crime and punishment; policymakers should not assume that they are a monolith or assume that victims’ interests always mean pushing for longer sentences and more carveouts.

Argument #3:“Including people charged with violent crimes in reforms will harm public safety”

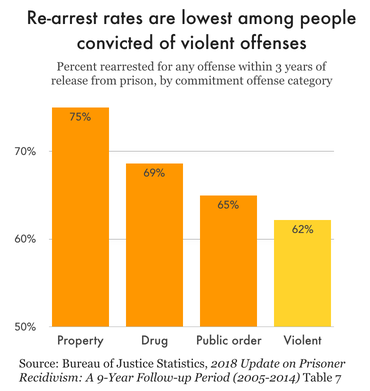

Carveouts are often rationalized with public safety arguments. Policymakers argue that releasing people convicted of violent crimes will harm community safety because they believe those people are likely to commit more violent crimes. In reality, re-arrest rates are lowest among people convicted of violent offenses.

When using these numbers with policymakers, advocates can remind them that these data include re-arrest for any crime, no matter how minor, as well as for technical violations of parole. Moreover, arrests are not the same as convictions; many of these charges are ultimately dismissed. Even though a majority of people released from prison were re-arrested within 3 years, research shows that very few people actually return to prison for a violent or sex-related offense:

- Safe and Just Michigan examined the re-incarceration rates of about 1,000 people convicted of homicide and sex offenses who were released on parole between 2007 and 2010. More than 99% did not return to prison within 3 years with a new sentence for a similar offense.

- In Maryland, a 2012 court case (Unger vs. Maryland), led to the release of nearly 200 people convicted of violent and sex-related crimes who had been incarcerated for over 30 years; as of 2018, only five had returned to prison for any reason. “The Ungers” were released with robust social support, which underscores the effectiveness of community-based programs in preventing people from returning to prison.

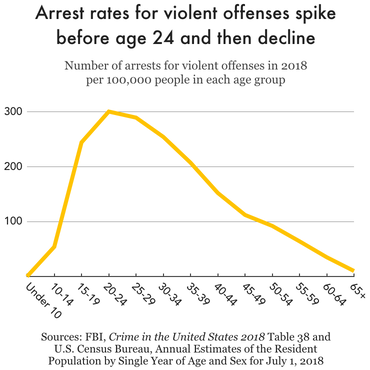

In the context of parole reform, where carveouts are pervasive, the age of people getting released also means that there is little reason to fear that crime will increase if people with violent charges are released. Research shows that risk for violent behavior is strongly dependent on age. Violent behavior is relatively rare for people in their 40s, 50s, and older, who are usually the people targeted for parole reform.

Argument #4:“People convicted of serious offenses do not deserve mercy or reform”

Sometimes, carveouts are rationalized with a moral argument: that people charged with violent or sex-related crimes, or crimes involving certain drugs, are universally people who are not deserving of reform or mercy.

This argument assumes that people convicted of serious crimes are all the same, and that their conduct is all equally violent or blameworthy. In fact, broad categories like “violent crime” often include a surprisingly wide range of criminal acts. In some states, manufacturing methamphetamines, purse snatching, and embezzlement are considered violent crime. When carveouts use these broad categories, they leave far more people out of reforms than those that the public would think of when they hear the term “violent crime.” Similarly, research has shown that the way that drug crimes are defined and enforced does not differentiate between higher level drug traffickers, street-level sellers, and users of drugs.

Even when the crime someone was convicted for was undeniably violent or serious, categorically excluding people from reforms ignores the immense growth and change people can undergo in the years and decades following the worst thing they have ever done. Categorical carveouts remove the ability of parole boards, prosecutors, judges, and other decisionmakers to look at cases individually, taking into account factors like the facts of the underlying crime, the wishes of any victims, the way someone has grown or changed since the original crime, and what supports or services the person will have access to if released. Every case is different.

Reforming our prison system cannot continue to focus on who is the most “deserving” of release. No other country on earth incarcerates as many people as the United States does. This includes countries with similar rates of violent crime as the United States. Our high incarceration rate is not a rational response to our crime rate; instead, it is the result of decades of failed policies that have led to immense human suffering and have not made us any safer.

Conclusion

The carveouts that have characterized the past two decades of criminal legal system reform are stifling progress and stalling attempts to reduce the prison population and bring the United States closer to alignment with the rest of the world. We hope that advocates and policymakers can work together to make criminal legal system reform available to everyone, so that we can see meaningful changes in our broken system.

Footnotes

There are also other kinds of restrictions on reforms that could be considered carveouts — for example, limiting reforms by age — but this guide will focus on charge-based carveouts. ↩

The distinction between “violent” and “nonviolent” charges is much less clear than it initially appears. As we discuss below, many state and federal laws apply the term “violent” to a surprisingly wide range of criminal acts, including many that do not involve any threat of physical harm. ↩