13 states in the hottest parts of the country lack universal A/C in their prisons. We explain the consequences.

by Alexi Jones,

June 18, 2019

Air conditioning has become nearly universal across the South over the last 30 years, with one exception: in prisons. Although 95% of households in the South use air conditioning, including 90% of households that make below $20,000 per year,1 states around the South have refused to install air conditioning in their prisons, creating unbearable and dangerous conditions for incarcerated people.

The lack of air conditioning in Southern prisons creates unsafe—even lethal—conditions. Prolonged exposure to extreme heat can cause dehydration and heat stroke, both of which can be fatal. It can also affect people’s kidneys, liver, heart, brain, and lungs, which can lead to renal failure, heart attack, and stroke.

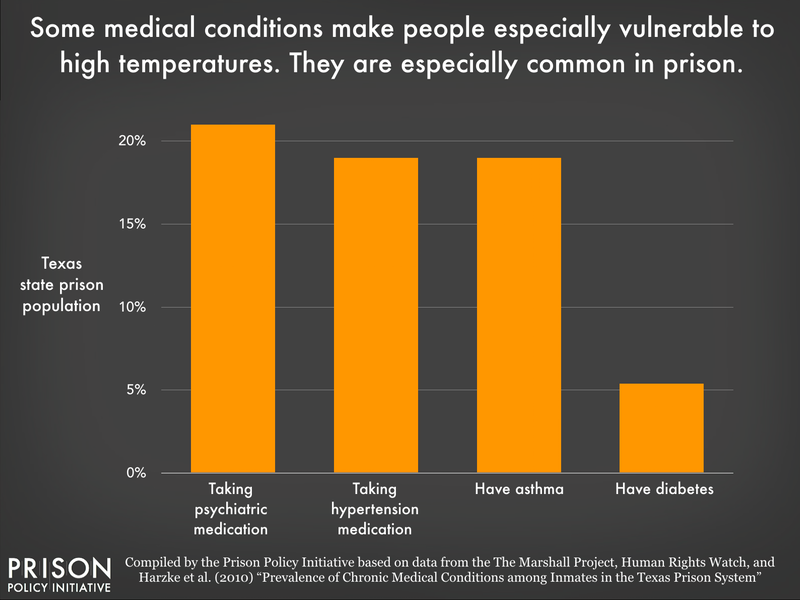

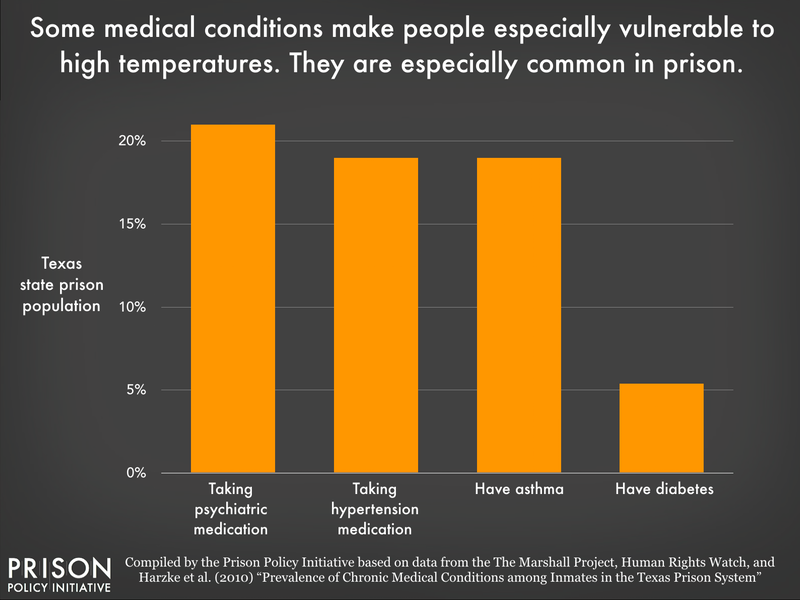

Many people in prison are especially susceptible to heat-related illness, as they have certain health conditions or medications that make them especially vulnerable to the heat. Conditions such as diabetes and obesity can limit people’s ability to regulate their body heat, as can high blood pressure medications and most psychotropic medications (including Zoloft, Lexapro, Prozac, Cymbalta, and more but excluding the benzodiazepines). Old age also increases risk of heat-related illness, and respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses, such as asthma, are exacerbated by heat.

In Texas, a state that has air conditioning in all inmate housing areas in only 30 of its 109 prisons, a high percentage of incarcerated people are particularly vulnerable to heat:

The structure of prisons and prison life can also make incarcerated people more vulnerable to heat. Prisons are mostly built from heat-retaining materials which can increase internal prison temperatures. Because of this, the temperatures inside prisons can often exceed outdoor temperatures. Moreover, people in prison do not have the same cooling options that people on the outside do. As Prison Legal News explains in a 2018 article on prison air conditioning litigation, “people outside of prison who experience extreme heat have options that prisoners often lack – they can take a cool shower, drink cold water, move into the shade or go to a place that is air conditioned. For prisoners, those options are generally unavailable.” Even fans can even be inaccessible. For example, despite the fact that incarcerated people in Texas are not paid for their labor, purchasing a fan from the Texas prison commissary costs an unaffordable $20.

The lack of air conditioning in prisons has already had fatal consequences. In 2011, an exceptionally hot summer in Texas, 10 incarcerated people died from heat-related illnesses during a month-long heat wave. (It’s just not incarcerated people who get sick from the heat in the state’s prisons. In August 2018, 19 prison staff and incarcerated people had to be treated for heat-related illnesses.) As David Fathi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union National Prison Project, explained to The Intercept, “Everyone understands that if you leave a child in a car on a hot day, there’s a serious risk this child could be injured or die. And that’s exactly what we’re doing when we leave prisoners locked in cells when the heat and humidity climb beyond a certain level.”

Courts in Wisconsin, Arizona, and Mississippi have ruled that incarceration in extremely hot or cold temperatures violates the Eighth Amendment. But these court cases have not had a national impact on air conditioning in prisons. As Alice Speri of The Intercept explains, “There’s no national standard for temperatures in prisons and jails, and as jurisdiction over prisons is decentralized among states and the federal system, and jurisdiction over jails is even more fragmented among thousands of local authorities across the country, fights over excessive heat in detention can only be waged facility by facility.” As a result, incarcerated people in the South are subjected to unbearable conditions that violate their basic human and constitutional rights. Benny Hernandez, an incarcerated man in Texas, describes how torturous heat gets in prisons: “It routinely feels as if one’s sitting in a convection oven being slowly cooked alive. There is no respite from the agony that the heat in Texas prisons inflicts.”

Refusing to install air conditioning is a matter not just of short-term cost savings, but of appearing tough on crime. State and local governments go to astonishing lengths to avoid installing air conditioning in prisons. In 2016, Louisiana spent over $1 million in legal bills in an attempt to avoid installing air conditioning on death row, an amount four times higher than the actual cost of installing air conditioning, according to an expert witness. Similarly, in 2014, the people of Jefferson Parish, LA only voted to build a new jail after local leaders promised there would be no air conditioning.

With air conditioning nearly universal in the South, air conditioning should not be considered a privilege or amenity, but rather a human right. States and counties that deny air conditioning to incarcerated people should understand that, far from withholding a “luxury,” they are subjecting people to cruel and unusual punishments, and even handing out death sentences.

Footnotes

Appendix

Examining local and national news stories, we identified 12 states in the South and Midwest that lack universal air conditioning and identified only Arkansas as having universal air conditioning.

| State |

Air Conditioning? |

| Alabama |

Prisons in Alabama do not have air conditioning. (Source) |

| Arizona |

Many prisons in Arizona lack air conditioning. (Source) |

| Arkansas |

Prisons have had air conditioning since the 1970s. (Source) |

| Florida |

State run prisons do not have air conditioning, but private prisons in the state do have air conditioning. (Source) |

| Georgia |

Most prisons have air conditioning, but some do not. (Source) |

| Kansas |

Most prisons do not have air conditioning. 70 percent of incarcerated people are in buildings without air conditioning. (Source) |

| Kentucky |

Most prisons do not have air conditioning. (Source) |

| Louisiana |

Most prisons do not have air conditioning. (Source) |

| Mississippi |

Most inmate housing in Mississippi has no air conditioning. (Source) |

| Missouri |

Some prisons lack universal air conditioning. (Source) |

| North Carolina |

Most prisons have air conditioning, but 10 facilities do not. (Source) |

| South Carolina |

Most prisons have air conditioning, but some facilities do not. (Source) |

| Texas |

30 of the 109 state prisons in Texas have air conditioning in all housing areas. (This is despite the fact county jails in the state are statutorily required keep their temperatures between 65 and 85 degrees). (Source) |

| Virginia |

Half of prisons have no air conditioning. (Source) |

As more jails ban face-to-face visits in favor of paid video chats, a growing number of people in jail are being cut off from their families when the technology breaks down.

by Sarah Watson,

June 18, 2019

Jails are increasingly replacing in person visits with video calls. This high-tech fad goes against the recommendations of the American Correctional Association, the American Bar Association, and even the Department of Justice’s National Institute of Corrections. These jails ignore the many problems we’ve documented, such as high costs for families, poor quality of the systems and the loss of human contact. But there’s another liability that jails now have to consider: What happens when their shiny new technology fails?

Their vendors — who provide the systems for free in exchange for charging high rates to the families — will say that their technology is perfect. As every person who owns a computer knows, however, technology is not flawless, and these systems do fail — sometimes keeping people in jail from contacting their families for weeks at a time:

We surveyed recent news stories about video systems breaking in jails that had chosen to replace traditional in-person visits with the technology.

| County |

State |

Time Down |

Year |

Details |

Source |

| Shelby County Jail (Memphis) |

Tennessee |

2 weeks |

2019 |

The vendor (GTL) cut a fiber optic cable |

Source |

| Virginia Beach Correctional Center |

Virginia |

3 months |

2018 |

Jail typically averages 4,000 visits a month |

Source1 Source2 |

| Williams County Correctional Center |

North Dakota |

2 months |

2017 |

System updates originally brought the system down, then it was discovered the upgrade was incompatible with the old equipment |

Source |

| Milwaukee County Jail |

Wisconsin |

At least one month |

2013-2014 |

Visual went down leaving only audio |

Source |

| Boone County Jail |

Arkansas |

“months” |

2018 |

Either a lightning strike or a software glitch brought the system down, administrators were not sure which was the cause. |

Source |

| Volusia County Branch Jail |

Florida |

One month |

2017 |

Lightning struck an integral part of the visitation system. It took multiple technicians to conclude the entire system needed to be replaced. |

Source |

| Pontotoc County Justice Center |

Oklahoma |

Three weeks |

2017 |

Visitation went down due to a “computer issue.” |

Source |

| Madison County Detention Center (Huntsville) |

Alabama |

>2 weeks |

2017 |

Planned system updates meant visits were suspended. |

Source |

| Montgomery County Detention Facility |

Alabama |

About a week |

2018 |

“Technical Issues” disrupted visitation as the jail waited for a replacement machine. |

Source |

| Olmsted County Adult Detention Center (Rochester) |

Minnesota |

1 day |

2018 |

The visitation system crashed, leaving visitors unable to schedule a visit or see their loved ones. The sheriff also confirmed the system sometimes goes down due to weather conditions as well. |

Source |

| Ada County Jail |

Idaho |

|

2019 |

Ada County Jail experiences consistent technical issues. One visitor to Ada County Jail recalled, “It didn’t work half the time. You’d have to call to see if [the system] was down.” |

Source |

| Mecklenburg County Jail (Charlotte) |

North Carolina |

|

2017 |

Frequent problems and system outages caused prisoners to miss their visits. “The video chat would go in and out. Sometimes half the screen would be cut off, and sometimes they wouldn’t work at all,” a former prisoner remembered. “You wouldn’t even get your visitation; you would have to wait until the next week, because even though the system was down, they would not make up the visitation you missed.” |

Source |

The good news is that counties are starting to take notice of the downsides to video calling. Most recently, the sheriff of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina (see table above) fulfilled a 2018 campaign promise to reinstate in-person visits, on the grounds that video should be used in addition to in person visits, not as a substitute.

“Allowing our residents to stay connected to family and loved ones through in-person visits improves public safety,” Sheriff McFadden explained. “This simple step alone has been shown to significantly lower the chances that a person will commit another crime after they get out. It also reduces the chance a person will commit an infraction inside the jail which could adversely impact their release. In addition, it improves mental health outcomes and strengthens family units and community ties.”

Mecklenburg County had the right idea. When this technology works, it should be considered a supplement to in-person visits, not a substitute; and when the technology fails, it’s useless. Instead of investing in flawed technology, jails should be looking for more ways to increase traditional methods of family contact.

The Democratic candidates are missing an opportunity to pitch sweeping criminal justice reform as an economic justice issue.

by Wanda Bertram,

June 12, 2019

Multiple Democratic presidential candidates have staked their campaigns on promises to fight for economic justice and protect low-income people from ruin. So it’s mysterious and frustrating that none of these candidates have proposed to end our justice system’s criminalization of poverty – at least beyond the occasional nod to ending money bail.

These candidates are missing an opportunity. The incomes of people in U.S. prisons and local jails are overwhelmingly low, and one in two American adults has had a close relative incarcerated, meaning that a candidate who understands the criminalization of poverty could propose transformative reforms and speak to a huge number of voters. In particular, candidates are missing an opportunity to speak to Black voters, who are hit hardest by policies that punish poor people.

To be sure, many Democratic candidates have alluded to economic inequality in connection with criminal justice reform — and Bernie Sanders even uses the phrase “criminalizing poverty” on his campaign website — but I’ve seen no indication that any of the candidates can speak to either the specifics or the scale of this problem. Candidates must go beyond criticizing money bail, and promise to end the unequal treatment of poor people at every stage of the justice process:

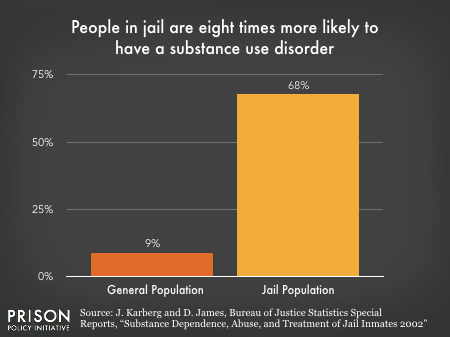

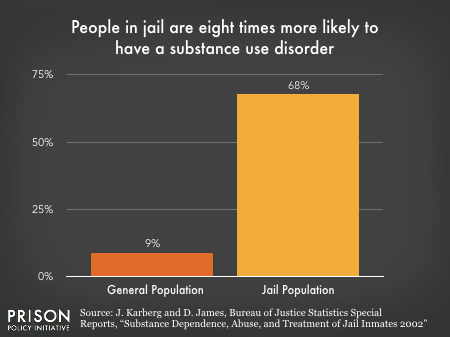

1. End poverty-related arrests and jail bookings. Far too many Americans who can’t afford housing, drug treatment or mental health services are instead arrested on minor charges related to their homelessness or illness. Many others end up in jail because they can’t afford burdensome fines and fees. An unfortunate downstream effect is jail overcrowding, which leads counties – largely in rural areas – to spend public money on harmful jail expansion rather than social welfare.

Presidential candidates should commit to helping state and local governments shift their priorities, making it easier to support low-income people and harder to jail them:

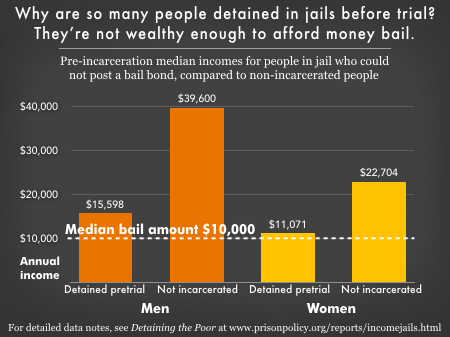

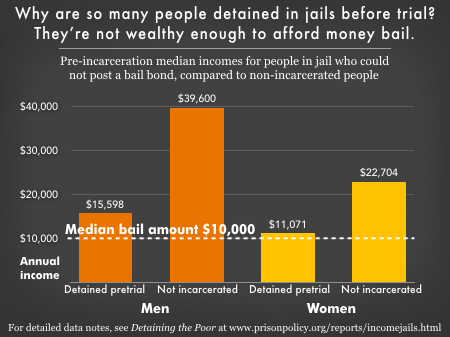

2. Guarantee poor people equal justice before trial. Two major injustices — pretrial detention and lack of access to counsel — ensure that low-income people are disproportionately convicted. Pretrial detention doesn’t just make defendants more likely to plead guilty; it also puts them at risk of losing their jobs and homes, and imposes huge costs on their families, before they’re ever convicted.

Candidates should promise to:

- Ensure that local public defender systems are fully funded, that they no longer charge co-pays to defendants, and that counsel is guaranteed at any hearing that could result in detention.

- Incentivize counties to drastically reduce pretrial detention by ending commercial money bail, and replacing it with release on recognizance, unsecured bonds, and other alternatives.

- Use the power of the Federal Communications Commission to regulate the cost of phone calls from jail, which can strain public defenders’ resources, not to mention those of family members.

- Subsidize county-level pretrial services to help low-income people make their court dates, such as text reminders and free childcare at court.

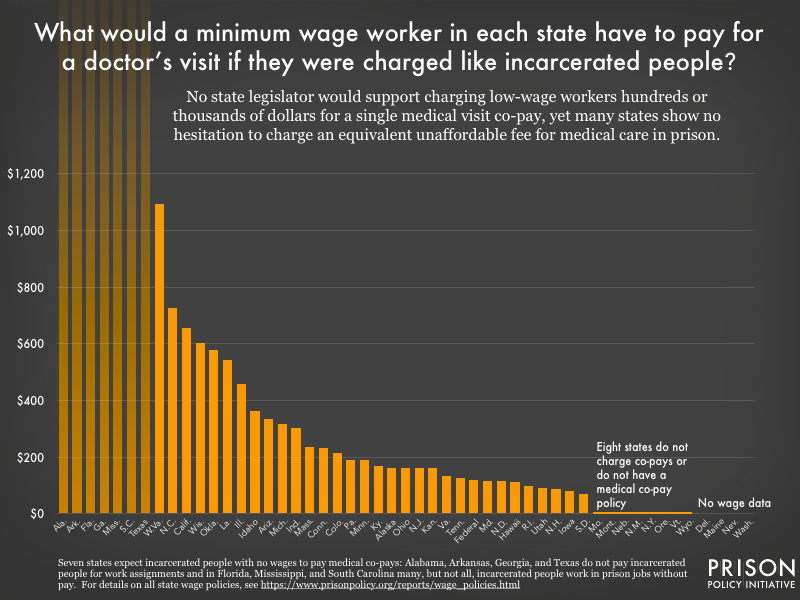

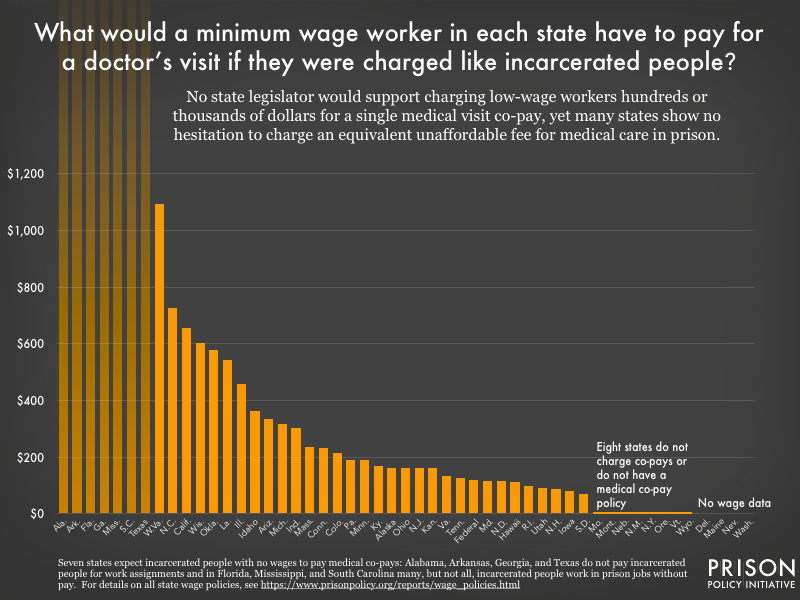

3. Stop forcing low-income families to subsidize the prison system. When someone goes to prison, their loved ones become their source of financial support. The financial pressure on these families grows when prisons fail to provide basic services, often driving families into debt. It shouldn’t be on relatives — disproportionately women — to pay for phone calls, medical care, nutritious food and educational resources for those behind bars, often when they’ve just lost a breadwinner.

Presidential candidates should commit to paying for incarcerated people’s needs to lift this burden on families:

4. Protect people from going back to prison just because they’re poor. Incarcerated people who come from under-resourced neighborhoods tend to return to those same neighborhoods after prison, now saddled with criminal records and far poorer than before.

Presidential candidates should avoid old narratives about how more surveillance, monitoring and job training are needed to “reduce recidivism” among people leaving prison. Instead, they should call the reentry process what it is: a period of extreme vulnerability that mostly affects impoverished people, and that can’t be improved without serious investments in formerly incarcerated people’s welfare. They should commit to:

- Identify the communities to which most formerly incarcerated people return, and subsidize additional low-income housing, drug treatment and mental health services in those communities.

- Help states create Departments of Reentry that connect people nearing release to permanent housing, medical care, and other resources.

- Incentivize states to pass laws expanding criminal record expungement, including automatic expungement for people convicted of minor offenses.

- End the harmful restrictions on association that prohibit formerly incarcerated people from helping each other rebuild their lives.

- Restore welfare benefits, including housing assistance, to people with criminal records.

- Urge states to abolish probation and parole fees, including fees for ankle monitors. End so-called “pay-only” probation schemes, which extract fees without providing any “services” at all.

- Incentivize states to “ban the box” on job applications, and to end restrictions on occupational licenses that lock people with criminal records out of good jobs.

- Expand federal tax benefits for businesses that hire people with criminal records.

- Incentivize states to end laws suspending driver’s licenses for non-driving offenses.

To be sure, there are many other policy changes that could help end the criminalization of poverty; this list is only a starting point. But it should be alarming that most of these policy options have gone unmentioned by any presidential candidate. Until the candidates commit to ending our criminal justice system’s abuse of poor people from arrest to release (and afterwards), their visions for economic justice won’t be complete.

A new government report reinforces harmful misconceptions about people convicted of sex offenses. Here's our take on how to parse the data.

by Wendy Sawyer,

June 6, 2019

By now, most people who pay any attention to criminal justice reform know better than to label people convicted of drug offenses “drug offenders,” a dehumanizing label that presumes that these individuals will be criminals for life. But we continue to label people “sex offenders” – implying that people convicted of sex offenses are somehow different.

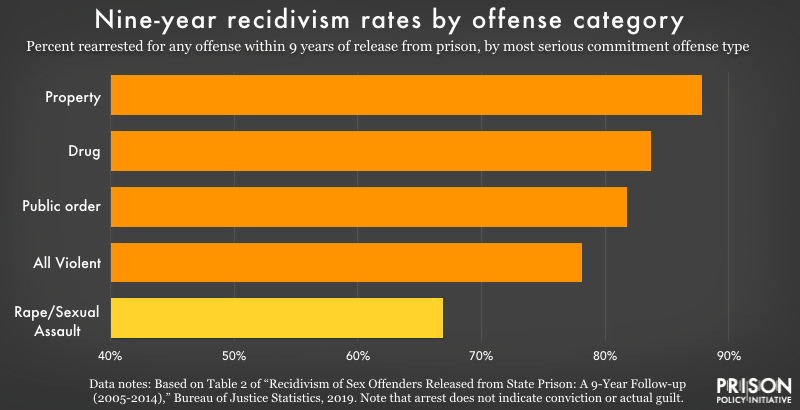

A new report released by the Bureau of Justice Statistics should put an end to this misconception: The report, Recidivism of Sex Offenders Released from State Prison: A 9-Year Follow-Up (2005-2014), shows that people convicted of sex offenses are actually much less likely than people convicted of other offenses to be rearrested or to go back to prison.

But you wouldn’t know this by looking at the report’s press release and certain parts of the report itself, which reinforce inaccurate and harmful depictions of people convicted of sex offenses as uniquely dangerous career criminals. The press release and report both emphasize what appears to be the central finding: “Released sex offenders were three times as likely as other released prisoners to be re-arrested for a sex offense.” That was the headline of the press release. The report itself re-states this finding three different ways, using similar mathematical comparisons, in a single paragraph.

What the report doesn’t say is that the same comparisons can be made for the other offense categories: People released from sentences for homicide were more than twice as likely to be rearrested for a homicide; those who served sentences for robbery were more than twice as likely to be rearrested for robbery; and those who served time for assault, property crimes, or drug offenses were also more likely (by 1.3-1.4 times) to be rearrested for similar offenses. And with the exception of homicide, those who served sentences for these other offense types were much more likely to be rearrested at all.

The new BJS report, unfortunately, is a good example of how our perception of sex offenses is distorted by alarmist framing, which in turn contributes to bad policy. That this publication was a priority for BJS at all is revealing: this is the only offense category out of all of the offenders included in the recidivism study to which BJS has devoted an entire 35-page report, even though this group makes up just 5% of the release cohort. This might make sense if it was published in an effort to dispel some myths about this population, but that’s not what’s happening here.

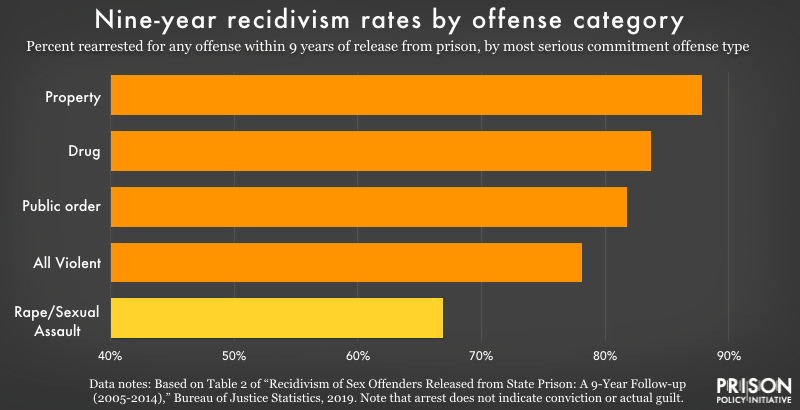

Framing aside, the recidivism data presented in the BJS report can offer helpful perspective on the risks posed by people after release. Whether measured as rearrest, reconviction, or return to prison, BJS found that people whose most serious commitment offense was rape or sexual assault were much less likely to reoffend after release than those who served time for other offense types. The BJS report shows that within 9 years after release:

- Less than 67% of those who served time for rape or sexual assault were rearrested for any offense, making rearrest 20% less likely for this group than all other offense categories combined (84%). Only those who served time for homicide had a lower rate of rearrest (60%).

- People who served sentences for sex offenses were much less likely to be rearrested for another sex offense (7.7%) than for a property (24%), drug (18.5%), or public order (59%) offense (a category which includes probation and parole violations).

- Only half of those who served sentences for rape or sexual assault had a new arrest that led to a conviction (for any offense), compared to 69% of everyone released in 2005 (in the 29 states with data).

While the data was more limited on returns to prison,1 the study found that within 5 years after release, people who had served sentences for rape or sexual assault also had a lower return-to-prison rate (40%) compared to the overall rate for all offense types combined (55%). BJS notes that some of these returns to prison were likely for parole or probation violations, but because of data limitations, it is impossible to say how many were for new offenses, much less how many were for rape or sexual assault.

In sum, the BJS data show that people who served time for sex offenses had markedly lower recidivism rates than almost any other group. Yet the data continue to be framed in misleading ways that make it harder to rethink the various harmful and ineffective punishments imposed on people convicted of sex offenses.

The recidivism data suggest that current legal responses to people convicted of sex offenses are less about managing risk than maximizing punishment. The desire for retribution is understandable; unquestionably, rape and sexual assault inflict serious and lasting trauma. But our criminal justice system does a poor job of providing survivors of rape, sexual assault, and other violent crimes what they really want. In a 2016 survey of crime survivors, the Alliance for Safety and Justice found that, “Survivors of violent crime — including victims of the most serious crimes such as rape or murder of a family member — widely support reducing incarceration to invest in prevention and rehabilitation and strongly believe that prison does more harm than good.” But more prison time is the default response: those released after serving sentences for rape and sexual assault served longer sentences, with a median sentence of 5 years (compared to 3 years for all others combined) and over a quarter serving 10 years or more before release.

And for many people convicted of sex offenses, confinement doesn’t end when their prison sentence does. Twenty states continue to impose indefinite periods of involuntary confinement under civil commitment laws – after individuals have completed a sentence (or, in some cases, before they are even convicted). Proponents justify the practice as “treatment,” but conditions of civil commitment are punitive and prison-like, and this confinement is hard to justify with the recidivism data we have. The likelihood of post-release arrest for another rape or sexual assault for this group is less than 2% in the first year out of prison, and after 9 years, less than 8% have been rearrested for a similar offense. Those who are released at age 40 or older are even less likely to be rearrested for another sex offense, with re-arrest rates about half those of people who are released at age 24 or younger.

After prison, a number of other special restrictions make reentry especially challenging for those who have served sentences for sex offenses, including registration, public notification, and restrictions to residence and employment. A current proposal suggests banning them from using New York City mass transit. (Even before release, some restrictions make it difficult for some people to leave prison when they would otherwise be paroled.) But these restrictions tend to cause more problems than they solve. Residence restrictions in particular have contributed to homelessness and other problems in cities where they leave little room for returning citizens. According to a 2015 U.S. Department of Justice brief, “residence restrictions may actually increase offender risk by undermining offender stability and the ability of the offender to obtain housing, work, and family support.”

In another recent academic article, Hanson et al. agree that these additional restrictions are “justified on the grounds of public protection,” even though the underlying assumptions may be wrong: “Individuals are targeted because policy-makers believe they are likely to do it again. This is a testable assumption, and, as it turns out, not entirely true.” Their analysis shows that individual recidivism risk varies widely, can be low enough to be indistinguishable from that of people convicted of non-sex offenses, and drops predictably over time. The data published by BJS track with those findings.

Collectively, the research seems fairly clear: our responses to people convicted of sex offenses do not reflect the actual – generally low – risks they present. Instead of panicking about the small portion who reoffend after release, it’s time we talk more rationally about responses that effectively support desistence from crime – and serve the actual needs of victims of violence.

Footnotes