Can you help us sustain this work?

Thank you,

Peter Wagner, Executive Director Donate

Does our county really need a bigger jail?

A guide for avoiding unnecessary jail expansion

By Alexi Jones

May 2019

Press release

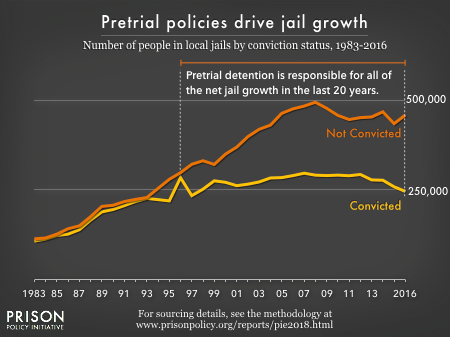

As jail populations have skyrocketed over the past three decades, jails around the country have become dangerously overcrowded. The reflexive response is often to start the long, expensive process of building a larger jail. However, this report provides a roadmap to easier, quicker, cheaper, and more just solutions to jail overcrowding. It is organized around a series of questions that local decisionmakers should be asking and then lays out a detailed briefing on best practices for reducing jail overcrowding.

Part 1: Questions to ask law enforcement, the judiciary, and jail expansion advocates

These questions are designed to help local decisionmakers determine how many people in their county’s jail are needlessly incarcerated, and whether the county has taken steps to reduce this number in order to avoid jail expansion.1 They are also meant to ensure the county has a full grasp of how much building a new jail will cost the community. Counties should not build a larger jail without getting answers from county sheriff departments, prosecutor offices, and jail administrators.

Is the county holding too many people in jail pretrial?

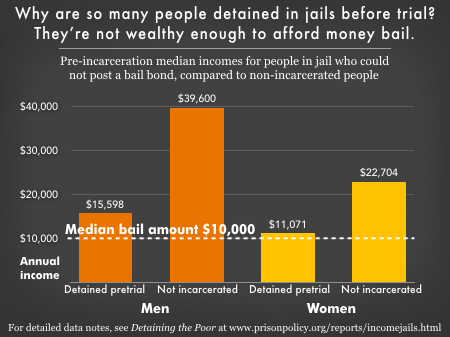

Nationally, the majority of people detained in jail are awaiting trial and are legally presumed innocent. Many people detained pretrial pose no public safety or flight risk but are incarcerated simply because they cannot afford cash bail. Recognizing this injustice, some counties around the country are reforming their pretrial release systems to prevent unnecessary pretrial detention. To judge whether pretrial detention should be reduced in the county, decisionmakers should ask:

- On a typical day, how many people are confined in our jail who have not been convicted?

- Have the police been instructed to expand their use of citations instead of making arrests the default response? How does our county’s use of citations compare to that of other counties that have managed to avoid expanding their jails?

- Does our county take an individual’s ability to pay into account when setting bail?

- Does our county use non-monetary bail, such as personal recognizance or unsecured bonds, as an alternative to money bail? How often is non-monetary bail used?

- How many people held pretrial have been arrested but not yet had a preliminary hearing?

- Has our county fully explored options that would get defendants before a judge — and hopefully released — more quickly? For instance, does our county have case monitors to continuously review which people coming into the jail could have their cases expedited?

- What guidelines or tools do judges use to determine which defendants are likely to appear in court and make it through the pretrial process without a new arrest — and should therefore remain in the community?

- Does our county offer pretrial services, such as court date notification services, to help people released pretrial make their court date?

Is the county incarcerating people because they cannot afford to pay fines and fees?

People who come in contact with the criminal justice system are disproportionately low-income, yet are often charged fines and administrative fees that can add up to thousands of dollars.

Those who cannot afford to pay are often punished with incarceration, despite the fact that the Supreme Court has ruled debtors’ prisons unconstitutional.2 To determine whether fees and fines are fueling incarceration in the county, decisionmakers should ask:

- How many people in our county are incarcerated because they cannot afford to pay fines and fees?

- How many warrants are issued and executed on the basis of a “failure to pay” or “failure to appear” at a proceeding related to fines and fees?

- Does our county take into account an individual’s ability to pay when imposing fees and fines?

- Does our county have payment plans, community service in lieu of payment, and exemption waivers available for poor defendants? How difficult are these alternatives to access and how often are they used?

Is the county incarcerating people with substance use and mental health disorders who should be treated in the community?

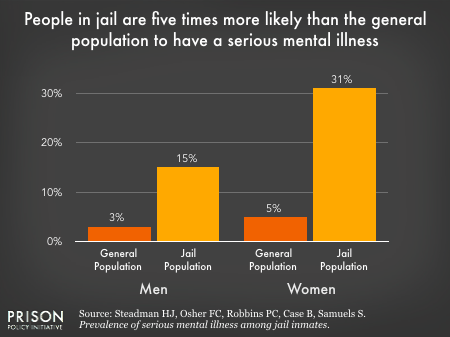

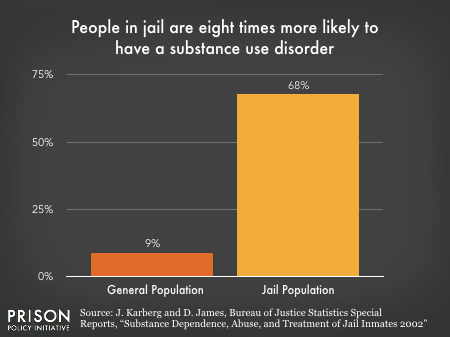

In the United States, people incarcerated in jails are five times more likely than the general population to have a serious mental illness,3 and 68% of the jail population meets medical standards for having a diagnosable substance abuse disorder. However, the majority of them do not receive appropriate treatment.4 The best solution is to invest in programs that divert people with mental illness and substance use disorder out of jail and into appropriate treatment in their communities. To determine how many people with mental illness and substance use disorder are incarcerated in the county, and whether the county has taken steps to reduce this number, local decisionmakers should ask:

- How many people in our jail have mental health or substance use disorders?

- Has our county explored starting or expanding community-based treatment programs to reduce the likelihood that people with substance use or mental health problems will be arrested?

- Does our county have specialized policing responses, such as crisis intervention teams (CITs) and police-mental health co-responder teams, that are designed to help link people with mental health and substance use treatment without arrest?

- What specialized “diversion” courts, such as drug, mental health, and veterans’ courts, is our county using to divert people into more effective treatments than jail? Is the treatment offered through this court evidence-based, such as Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)? Is it free and accessible to all?

Is the county overincarcerating people convicted of misdemeanors and low-level offenses?

Even for people who have been convicted, incarceration may not be an appropriate solution. The majority of people in jail who have been convicted are incarcerated for nonviolent offenses, and could be better served in the community rather than in jail. To determine the extent that misdemeanors and low-level offenses contribute to the county’s jail overcrowding, decisionmakers should ask:

- How many people in our jail have been convicted of non-violent misdemeanors and low-level offenses?

- Does our county offer jail diversion programs for people convicted of misdemeanors and low-level offenses? Are these programs affordable and accessible to all?

- Does our county have case monitors that continually review people coming into the jail to identify those who could be diverted?

- Has our county increased its use of diversion programs in order to reduce jail overcrowding?

- What is the average sentence length for people incarcerated in our county’s jail? How does this compare to counties that have reduced their jail populations?

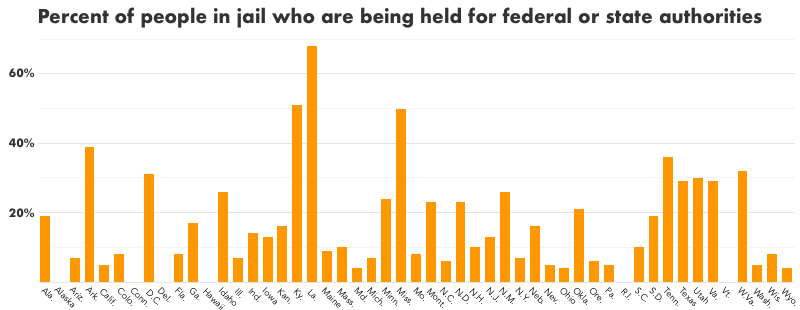

Is the county using its limited jail space to hold people for other authorities?

As of 2013, 84 percent of jails held some people, either pretrial or sentenced, for other county jails, state prisons, or federal authorities like the Federal Marshals, the Bureau of Prisons, or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). To determine whether ending contracts with other authorities would reduce overcrowding in the local jail, decisionmakers should ask:

- How many people in our county jail are being held for other authorities, such as other counties, state prisons, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), or the U.S. Marshals?

- Has the county stopped renting jail beds to other authorities in order to avoid expanding its jail?

- How many people in our county jail have been sentenced and are awaiting transfer to state prison?

Figure 5. In 25 states, one out of every ten people in jail is actually being held for state or federal authorities. Data is not available for Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Vermont, which do not have separate jail systems. The data behind this graph is available here.

Figure 5. In 25 states, one out of every ten people in jail is actually being held for state or federal authorities. Data is not available for Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Vermont, which do not have separate jail systems. The data behind this graph is available here.

Does the jail hold a lot of people for minor parole and probation violations?

Many people are in jail for violations of their probation or parole. Frequently, these are technical violations, which are violations of probation and parole rules that are not criminal offenses, but can still result in incarceration. For example, someone on probation or parole can be sent to jail or prison for failing to report for a scheduled office visit, missing curfew, failing to obtain employment or attend school, or testing positive for drugs or alcohol. County probation, state probation, and state parole offices should prioritize helping people succeed in the community rather than returning people to incarceration. To determine whether minor probation and parole violations are contributing to jail overcrowding, local decisionmakers should ask:

- How many people in our county jail are being held for technical violations of probation and parole?

- Does our county cap how long people can be incarcerated for parole and probation violations?

- How often are sanctions other than jail time used to address parole and probation violations? Does our probation office use a system of graduated sanctions that allow jail only as a last resort?

How much will building the new jail really cost the county?

Jails often cost far more than communities anticipate. Constructing a new jail often costs the county tens of millions of dollars. It also diverts a large portion of the county’s budget, preventing them from investing in education, drug treatment, affordable housing, and other services that could reduce crime and incarceration. To determine how much building a new jail will cost the county and its residents, local decisionmakers should ask:

- How much is the new jail estimated to cost our county? Does that figure include the cost of constructing the new jail, the cost of the debt service on the loan, and the annual costs of operating the jail?

- How will the annual costs of operating the new jail compare to the cost of operating the current jail? Does the new operating cost include the cost of hiring and paying salaries to additional guards and supervisory staff?

- Will this construction require any tax increases for county residents?

- If it does not require tax increases, what services or programming is our county planning on cutting to fund the jail expansion?

- What other county agencies (such as the county’s public health or education agencies) will have increased costs (healthcare and education programs for incarcerated people) because of jail expansion? How much do you estimate their costs will increase per year?

- Do official cost estimates take into account the collateral costs of incarceration on people, families, and communities, including loss of wages and jobs, adverse health impacts, increased child welfare costs, and the costs to stay in touch with loved ones?

Part 2: Best practices for reducing jail overcrowding

This section details six practices counties can use to reduce jail overcrowding, examples of jurisdictions that have used these practices to lower their incarceration rates, and additional resources on each practice. Each of the practices laid out in this section can be effective independent of the others. However, for the maximum effect, we recommend using all of these strategies.

It’s worth noting that many of the best practices discussed in this report use examples from large urban counties, and there are important differences between these counties and the rural counties where jail growth is now concentrated. However, rural counties can benefit from the experiences of larger jurisdictions that have assumed the much of the early risk of these innovations and reforms and can find ways to adapt those lessons in the rural communities where it is now most urgently needed.

Reforming pretrial detention

Nationally, 76% of people held by local jails are not convicted of a crime and are legally presumed innocent. While some people are incarcerated because they pose a significant safety or non-appearance risk, many are there simply because they cannot afford to pay cash bail. This creates a two-tiered justice system in which people who have enough money to pay cash bail are released, while poor Americans are forced to remain in jail as their case moves through the system. There are also significant racial disparities in pretrial detention, as Black and Hispanic individuals accused of crimes are more likely to be detained pretrial compared to similarly situated white individuals.

Pretrial detention can have devastating impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Even a few days in jail can drastically interfere with people’s employment, housing, healthcare, and child custody, and research suggests that even brief jail stays (particularly for low-risk defendants) can increase an individual’s chance of committing a future crime.5 Pretrial detention is also extremely expensive for counties. Together, local communities spend at least $14 billion every year to detain people who have not been convicted.

As more states and counties move away from unnecessary pretrial detention, research has demonstrated that reforming pretrial detention does not lead to an increase in crime rates, recidivism, or failures to appear in court.6 Counties have implemented the following reforms to reduce their pretrial detention populations:

- Issuing citations in lieu of arrests: In order to reduce the number of arrests that lead to jail bookings, police can issue citations to people instead of arresting them, which allows defendants to wait for their court date at home without having to go to jail or post money bail.

- Taking into account an individual’s ability to pay when setting bail: Counties should require that judges only set bail in amounts that defendants can afford to pay. Courts around the country have ruled it unconstitutional to set bail without considering the defendant’s ability to pay, and that when a court detains someone pretrial on unaffordable bail, it must meet the same standards of scrutiny as it would with a preventative detention order. Failure to take ability to pay into account has led to costly litigation in Harris County, TX; Randolph County, AL; Cook County, IL; Lafayette Parish, LA; and other jurisdictions.

- Releasing people on recognizance: Releasing someone on recognizance is a non-financial form of bail in which someone is released with the promise that they will attend all required judicial proceedings and that they will not engage in illegal activity or other prohibited conduct as set by the court.

- Using unsecured bonds: Unsecured bonds allow defendants to be released pretrial without paying any money unless they do not appear for court. Research indicates that unsecured bonds are as effective at achieving public safety and court appearance as money bail and much more effective at freeing up jail beds.

- Offering pretrial services: Counties should adopt evidence-based pretrial services to ensure that people released make their court appearances. For example, court date notification messages are a cost-effective way to increase court appearances. However, pretrial services should be minimally restrictive. For example, electronic monitoring and regularly meeting with a pretrial officer can interfere with people’s ability to succeed in the community and have not been shown to improve pretrial outcomes. All costs of pretrial supervision should be borne by the county, not the individual.

- Being cautious of validated risk assessments: A pretrial risk assessment is an algorithm that is intended to determine the likelihood that a person, if released, will show up for court and not engage in criminal activity during the pretrial period. Unlike many of the proposals in this briefing, risk assessments are controversial. Most criminal justice reform organizations now agree that risk assessments can actually lead to worse outcomes, and other strategies are more effective for reducing pretrial populations. Not only can risk assessments perpetuate or exacerbate racial disparities in our criminal justice system, but recent studies have also called into question how reliable risk assessments’ predictions are and whether using them necessarily decreases pretrial detention. Therefore, if using a pretrial risk assessment, counties should exercise extreme caution.7

Reforming pretrial detention has allowed counties to dramatically reduce their jail populations:

- Over the past two decades, Washington, DC has virtually eliminated cash bail and has implemented a robust pretrial services program. Its Pretrial Services Agency evaluates the risk for all people booked and recommends appropriate services and supervision levels for all who are released. The majority of people are released on personal recognizance with no supervision. Even though only 9% of people arrested are detained pretrial, DC has maintained high appearance rates (89%) and has not compromised public safety (99% of people released are not rearrested pretrial for a violent crime).8

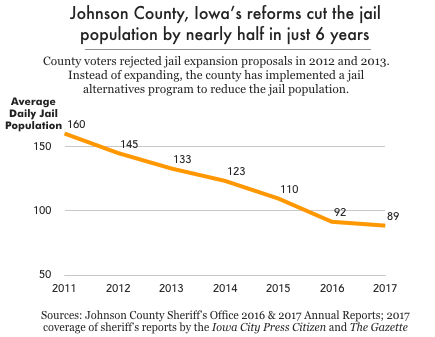

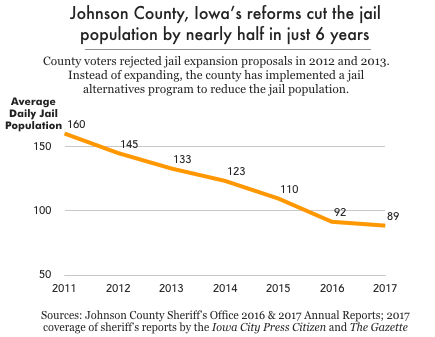

After voters in Johnson County (Iowa City), Iowa, rejected jail expansion proposals in 2012 and 2013, the county addressed jail overcrowding by reducing their use of pretrial detention and implementing other reforms. The jail, law enforcement, prosecutors, and judges worked together to ensure that people who were low-risk were not needlessly incarcerated pretrial, by increasing the number of people released on their own recognizance. As a result, the jail’s average daily population dropped by 44% (from 160 people to 89 people) between 2011 and 2017, which saved the county nearly $500,000 in 2016 alone.

After voters in Johnson County (Iowa City), Iowa, rejected jail expansion proposals in 2012 and 2013, the county addressed jail overcrowding by reducing their use of pretrial detention and implementing other reforms. The jail, law enforcement, prosecutors, and judges worked together to ensure that people who were low-risk were not needlessly incarcerated pretrial, by increasing the number of people released on their own recognizance. As a result, the jail’s average daily population dropped by 44% (from 160 people to 89 people) between 2011 and 2017, which saved the county nearly $500,000 in 2016 alone.

For more information on reforming pretrial detention:

- Bail Reform: A Guide for State and Local Policymakers (Harvard Law School’s Criminal Justice Policy Program)

- A New Vision for Pretrial Justice in the United States (ACLU)

- What’s Happening in Pretrial Justice? (Pretrial Justice Institute)

- Pretrial Services Program Implementation: A Starter Kit, (Pretrial Justice Institute)

- The Use of Pretrial “Risk Assessment” Instruments: A Shared Statement of Civil Rights Concerns (Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights)

Reforming how counties issue fees and fines to ensure low-income people are not being punished for being poor

People who come in contact with our criminal justice system are disproportionately poor, but are often charged fines and fees that are impossible for them to pay. People are charged fines as sanctions for anything from municipal or traffic violations to felony cases. On top of fines, people are often charged numerous fees as they move through the court and criminal justice system, including pre-sentence report fees, public defender fees, fees for electronic monitoring, pay-to-stay fees, supervision fees, and more. When fines and fees are issued, people’s ability to pay is rarely taken into account. As a result, people, especially people of color,9 can end up saddled with thousands of dollars of criminal justice debt that they have no hope of paying off.

When people are not able to pay off their criminal justice debt, they are subject to even more sanctions. These include additional fines and fees, interest, driver’s license suspension, extension of supervision, and even incarceration. In some jurisdictions, as many as 20% of people in local jails are incarcerated because they could not afford to pay court-imposed fines and fees.

Counties should stop incarcerating people for their inability to pay fines and fees and should implement the following reforms:

- Holding hearings to assess an individual’s ability to pay when setting fines and fees

- Offering payment plans, at no additional cost

- Eliminating interest and unnecessary late fees

- Giving people the option of completing community service in lieu of payment

- Offering fee waivers to the indigent

Counties must also ensure that they do not issue sanctions that limit people’s ability to work or earn money and thereby pay off their fees, such as driver’s license suspension.

Some states and counties have taken steps to limit the number of people incarcerated for unpaid court-related debt, which has allowed them to decrease their jail populations and dedicate resources to protecting public safety, rather than incarcerating the poor. For example:

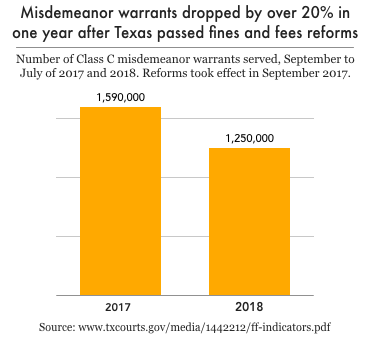

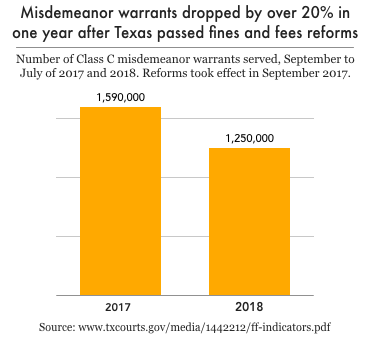

In 2017, the Texas legislature passed a law that requires judges to “determine a defendant’s ability to pay fines and costs at sentencing, allows judges to waive or reduce fines and fees, and provides for sentencing alternatives when the defendant is unable to pay fines and fees, and it limits arrests and incarceration for inability to pay fines and fees.” As a result of this legislation, the number of people incarcerated for failure to pay fines declined by 26% and 300,000 fewer arrest warrants were issued for failure to pay fines and fees.10

In 2017, the Texas legislature passed a law that requires judges to “determine a defendant’s ability to pay fines and costs at sentencing, allows judges to waive or reduce fines and fees, and provides for sentencing alternatives when the defendant is unable to pay fines and fees, and it limits arrests and incarceration for inability to pay fines and fees.” As a result of this legislation, the number of people incarcerated for failure to pay fines declined by 26% and 300,000 fewer arrest warrants were issued for failure to pay fines and fees.10 - In 2010, Leon County (Tallahassee), Florida prohibited jail time for unpaid fees. It closed its collections court and terminated approximately 8,000 outstanding arrest warrants for nonpayment. As a result, the county arrested an estimated 800 fewer people per year for criminal justice debt, which would account for 20,000 hours of jail time.

For more information on fees and fines justice, see:

- Confronting Criminal Justice Debt: A Guide for Policy Reform (Harvard Law School’s Criminal Justice Policy Program)

- Criminal Justice Debt: A Toolkit for Action (Brennan Center for Justice)

- Trends in State Courts Fines, Fees, and Bail Practices: Challenges and Opportunities (National Center for State Courts)

Ensuring people with mental health and substance use disorders are treated, not incarcerated

It is estimated that 2 million people with mental illness are booked into jails each year. Nationally, about 15% of men and 31% of women in jails have a serious mental illness compared to 3% and 5% percent in the general population. And about 68% of the jail population meets medical standards for having a diagnosable substance use disorder.

It is estimated that 2 million people with mental illness are booked into jails each year. Nationally, about 15% of men and 31% of women in jails have a serious mental illness compared to 3% and 5% percent in the general population. And about 68% of the jail population meets medical standards for having a diagnosable substance use disorder.

Despite the high rates of mental health and substance use disorders, jails rarely have adequate resources available, nor are they the appropriate places, to treat people with mental health and substance use disorders. This can have devastating consequences. Research has shown that in the two weeks after their release, recently incarcerated people are 40 times more likely to die from an overdose than the general population.

Instead of incarcerating people with mental health and substance use disorders, counties should invest in a public health approach. First and foremost, counties should ensure that everyone in the community has access to evidence-based substance use treatment and mental health care, which can prevent criminal justice involvement in the first place. Research has demonstrated that access to substance use treatment can reduce both violent and financially motivated crimes in a community. Moreover, investing in substance use treatment is estimated to yield a $12 return for every $1 spent, as it reduces future crime, costly incarceration, and lowers health care expenses.

Secondly, counties should implement the following reforms to divert those who do come in contact with the criminal justice system:

- Crisis intervention teams: Crisis intervention team (CIT) programs are police-based pre-arrest crisis intervention programs designed to divert people with mental illnesses from the criminal justice system to appropriate treatment. Under this model, a select group of police officers receive intensive, special mental health training (which includes information on signs and symptoms of mental illnesses, treatment, de-escalation techniques, etc.). This training helps police respond appropriately to mental health crisis situations and divert people with mental health disorders to treatment and services rather than jail. Although originally designed for urban counties, crisis interventions can also work in rural counties.

- Police-mental health co-responder teams: Under this model, mental health professionals assist the police during police interactions with people experiencing mental health crisis. This model helps law enforcement de-escalate the situation, avoid arrest, and link people with mental health disorders to appropriate treatment and services. Both CIT programs and police-mental health co-responder teams are especially valuable tools for reducing jail overcrowding in counties where prosecutors are not reform-minded.

- Establish mental health and drug courts that function as alternative to, rather than a precursor to incarceration: Counties should establish specialized problem-solving courts for people with mental health disorders or substance use disorders that serve as true alternatives to incarceration. In these specialized courts, multidisciplinary teams, including judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, social workers and treatment service professionals, work together to help people into treatment and connect them with services. Since the diversion moves people out of the criminal justice system, participation should not saddle participants with a criminal conviction, which make it harder for them to find employment, housing, and get access to government services.

Unfortunately, many mental health and drug courts set participants up to fail, and therefore function more as drivers of incarceration than as alternatives to it. For example, the medical gold standard for opioid dependence treatment is medication-assisted treatment. However, half of drug courts do not offer medication-assisted treatment. Furthermore, although the medical community understands that relapse is often a normal part of recovery, many drug courts require abstinence and punish relapse with incarceration. In order to be effective, drug courts and mental health courts must offer evidence-based treatment in line with medical best practices.

Establishing these programs can be more difficult in smaller communities. However, rural counties with limited behavioral health services should consider developing partnerships with neighboring counties, which can provide opportunities to share services, resources, and funding for treatment.

Counties and states around the country have implemented programs to avoid jailing people with mental health or substance use disorders:

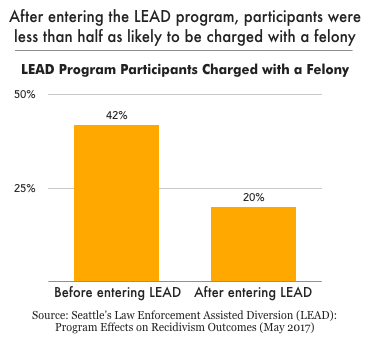

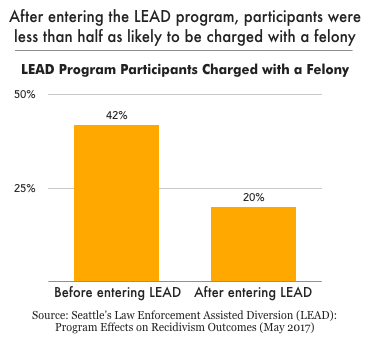

In 2011, Seattle developed a Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) Program, in which law enforcement connects people suspected of low-level drug and prostitution offenses directly to treatment and services, rather than prosecution and incarceration. Researchers found that LEAD participants were 60% less likely to be arrested in the six months following their entry into the program, and were both 58% less likely to be arrested and 39% less likely to be charged with a felony over the following five years.

In 2011, Seattle developed a Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) Program, in which law enforcement connects people suspected of low-level drug and prostitution offenses directly to treatment and services, rather than prosecution and incarceration. Researchers found that LEAD participants were 60% less likely to be arrested in the six months following their entry into the program, and were both 58% less likely to be arrested and 39% less likely to be charged with a felony over the following five years. - In 2000, Miami-Dade County (Miami), Florida, started the Miami-Dade Mental Health Program, a diversion program for people with mental illnesses that has been hailed as a national model for decriminalizing mental illness. The program links people with mental illness who come into contact with the criminal justice system with treatment and services. The program consists of Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) for pre-booking diversion as well as a post-booking diversion program for people awaiting adjudication. Since the Criminal Mental Health Project began, the daily jail population in Miami-Dade County has dropped from 7,200 to 4,000, one jail facility has been closed, and fatal shootings and injuries of mentally ill people by police officers have dropped dramatically. This has saved the county millions of dollars each year.

- Over the past 16 years, several towns in Massachusetts have implemented Pre-Arrest Co-Responder Jail Diversion Programs. Since 2003, 2,445 individuals have been diverted from arrest as a result of this program by co-responding clinicians, which has resulted in estimated cost savings of $4,890,000.

For more on mental health and substance use diversion, see:

- University of Memphis, CIT Program

- Sheriffs Addressing the Mental Health Crisis in the Community and in the Jails (Community Oriented Policing Services)

- A Guide to Implementing Police-Based Diversion Programs for People with Mental Illness (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration)

- A Technical Assistance Guide For Drug Court Judges on Drug Court Treatment Services (Bureau of Justice Assistance Drug Court Technical Assistance Project)

Creating alternatives to incarceration for people convicted of misdemeanors and low-level offenses

Even for people who have been convicted, incarceration may not be an appropriate response. Three-quarters of people in jail who have been convicted are incarcerated for nonviolent offenses. For people convicted of such low-level crimes, incarceration is tremendously counterproductive: It cuts them off from people and programs that could help them turn their lives around while yielding virtually no benefits to public safety.

Counties can reduce the number of people with misdemeanor convictions in local jails by:

- Reducing the number of jailable offenses: States and counties can reduce their jail populations by reducing the number of jailable offenses, thus reserving jail only for people who pose a demonstrable threat to public safety. For example, states and counties can make some offenses civil matters, and re-classify others as non-jailable offenses. If state law does not allow a county to reclassify offenses, the county should lobby the state to do it.

- Encouraging prosecutors to be less punitive: District attorneys have a lot of discretion in whom they choose to prosecute and what charges they bring, giving them enormous power to reduce jail populations if they are reform-minded. Prosecutors can decline to prosecute minor, low level offenses and instead pursue non-carceral sanctions in order to reduce jail populations.

- Encouraging judges to give shorter sentences: Shortening sentences is a key tool for reducing jail populations.

- Diversion programs and alternatives to incarceration: Police, prosecutors, and judges should be encouraged to connect people with diversion programs that seek to address the underlying cause of the offense, rather than pursuing jail time. For example, alternatives to incarceration could provide vocational training, literacy and educational support, counseling, mentoring, or residential and outpatient mental health and substance use treatment. Research has demonstrated that diversion programs can dramatically cut reoffending rates and improve employment outcomes compared to incarceration. Counties should ensure that diversion programs are free and accessible and that the programs allow people to avoid the collateral consequences of a criminal conviction. If necessary, rural counties with limited resources should consider collaborating with neighboring counties to fund and create evidence-based diversion programs.

- Sentencing people to probation in lieu of incarceration: Probation, by design, is an important alternative to incarceration. In cases where incarceration is the only practical alternative, probation should be used to minimize the broad social and economic harms of incarceration. But counties should be wary of using probation as a knee-jerk response to low-level offenses (it’s been used for things as minor as nonpayment of fines). When used, probation should be minimally restrictive, not fee-based, individualized, and short in length.

For example:

- In 2018, the Manhattan District Attorney decided to decline prosecuting public transportation fare evasion if there are no threats to public safety. Instead, people caught evading fares may be warned, ejected, connected with social services, issued a civil ticket, or issued a criminal ticket. As a result, the number of fare evasion prosecutions declined by 96% in the first year alone.

- In St. Louis, Missouri, the District Attorney announced that prosecutors will no longer pursue charges for most low-level marijuana offenses. Prior to this announcement, lower-level marijuana crimes made up about 20 percent of the prosecution docket.

- As discussed above, Seattle, Miami-Dade County, and several towns in Massachusetts have implemented diversion programs specifically designed for people with mental health and substance abuse disorders.

For more information on alternatives to incarceration:

- Unlocking the Black Box of Prosecution (Vera Institute of Justice)

- Promising Practices in Prosecutor-Led Diversion (Fair and Just Prosecution)

- Handbook of basic principles and promising practices on Alternatives

to Imprisonment (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) - How Many Americans Are Unnecessarily Incarcerated? (Brennan Center for Justice)

Stop renting jail beds to other authorities in order to reduce jail overcrowding

In 2013, 8 in 10 jails held people, either pretrial or sentenced, for other county jails, state prisons, or federal authorities such as the U.S. Marshals Service, the Bureau of Prisons, or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). As a result, 22% of people held in local jails nationwide are not under the jurisdiction of the jail in which they are incarcerated. County jails are either required or financially incentivized to hold people under federal (such as the U.S. Marshals Service or ICE) or state jurisdiction. However, accommodating these agencies can pose additional burdens on county jail systems, and relying on these contracts for revenue can backfire when, due to policy changes outside of local control, the state or federal system’s need for jail space dwindles.11 By stopping their practice of renting out beds, counties have been able avoid building larger jails altogether:

- Officials in Blount County (near Knoxville), Tennessee used “jail overcrowding” to justify a proposal for jail expansion. However, a deeper analysis revealed that the county’s jail was overcrowded in large part because it was renting space to the state prison system. The county has now cut back on renting space to the state prison system and is exploring other ways to reduce its jail population.

For more information on how many people your county is incarcerating for other authorities, see:

- Jail Population Held for Other Authorities (Vera Institute of Justice)

Ensuring people are not sent to jail for technical violations of probation and parole

Probation and parole impose conditions that make it difficult for people to succeed, and therefore end up channeling people into prisons and jails. People on probation and parole are often subject to intense surveillance and a long list of restrictions that, if not met, can land them in jail. In fact, the leading reason for revocation of probation and parole is not new crimes, but technical violations, such as being out past curfew, testing positive for drug usage, or traveling to another state without permission. Every year, 350,000 people, disproportionately people of color, have their probation or parole revoked. Some counties have found that as many as 14% of people booked into their jails are there for technical violations.

In some states, counties have authority over felony and or misdemeanor probation. And in all states, county jails end up carrying the consequences of state decisions on the revocation of probation and parole. Counties can reduce their jail populations by:

- Not sending people under their jurisdiction to jail for technical violations: Instead, counties should determine what caused the individual to violate the terms of their probation and address the underlying issue.

- Ensuring that county probation, state probation, and state parole offices are making it their priority to help people under community supervision succeed in the community.

Some counties and states around the country have gradually started reforming their probation and parole systems.

- In 2017, Louisiana passed legislation that decreased the number of technical violation revocations by 53% and the average length of stay for revocations by 31%. The legislation banned the use of jail as a sanction for 1st and 2nd low-level probation and parole violations, capped the length of jail time for violations, and expanded the pool of violations for which officers can respond with administrative sanctions.

For more information:

- Toward an Approach to Community Corrections for the 21st Century: Consensus Document of the Executive Session on Community Corrections (Harvard Kennedy School Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management)

- Too big to succeed: The impact of the growth of community corrections and what should be done about it (Columbia University Justice Lab)

- Rethinking the Use of Community Supervision(Cecelia Klingele, Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice)

Conclusion

Before beginning the long, expensive process of building a new jail, counties must take a critical look at who they are incarcerating and why. Using this report as a guide, counties will likely find that most people incarcerated in their local jail do not need to be incarcerated and would be better served in the community, allowing the county to avoid the costly and harmful route of jail expansion altogether.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. Through accessible, big-picture reports, the organization helps the public engage more fully in criminal justice reform. Its previous reports Era of Mass Expansion and Detaining the Poor helped put the need for jail and bail reform into the national conversation. The Prison Policy Initiative also leads the nation’s fight against prison-based gerrymandering and plays a leading role in protecting the families of incarcerated people from the predatory prison and jail telephone and video calling industries.

About the author

Alexi Jones is a policy analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative, and a graduate of Wesleyan University, where she worked as a tutor through Wesleyan’s Center for Prison Education. Before joining the Prison Policy Initiative, Lexi conducted research related to health policy, neuroscience, and public health. Since joining the Prison Policy Initiative, Lexi has authored Correctional Control 2018: Incarceration and supervision by state, which shows that prison is just one piece of the much larger picture of correctional control, discusses the harms of probation in particular, and provides breakdowns of the criminal justice system in each state. Most recently, she co-authored State of Phone Justice: Local jails, state prisons, and phone providers with Peter Wagner.

Acknowledgements

This report was made possible thanks to the generous support of the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, and the contributions of individuals across the country who support justice reform. This report benefitted from the expertise and input of many individuals. Lois Ahrens, Jerry Zorsch, Jasmine Heiss, Laurie Jo Reynolds, and Craig Gilmore provided invaluable feedback for this report. I am also indebted to Wendy Sawyer, Wanda Bertram, and Peter Wagner for their support throughout the writing process, and Emily Widra and Maddy Troilo for their research support.

Footnotes

When assessing the need for a new jail, counties often rely on future jail population projections, which are often based on projections of overall county population growth, and assume no change to current offense patterns or practices in law enforcement, prosecution, and sentencing. Such projections can be unreliable, and may overstate the county’s true jail needs, especially if the county implements reforms to reduce the jail population before expanding jail capacity. ↩

The U.S. federal government outlawed debtor’s prisons nearly 200 years ago. In 1970, the Supreme Court ruled that extending a maximum prison term because a person is too poor to pay fines or court costs violates the right to equal protection under Fourteenth Amendment in Williams v. Illinois. And, in the 1983 case Bearden v. Georgia, the Supreme Court ruled local government cannot imprison or jail someone for not paying a fine unless it can be shown through a hearing that the person in question could have paid it but “willfully” chose not to do so. ↩

Data collected 2002-2003 and 2005-2006 revealed that 14.5% of males and 31.0% of females in jails have a current serious mental illness. In contrast, 3.2% of men and 4.9% of women in the general population have a diagnosable serious mental illness. ↩

Only one third of people in jail experiencing serious psychological distress receive appropriate treatment. Similarly, research has shown that only a quarter of people only a quarter of people in jail with substance use disorders received treatment. ↩

Research has shown that incarceration can be counterproductive and increase the frequency and severity of recidivism. For more information, see:

- Mueller-Smith, Michael. “The Criminal and Labor Market Impacts of Incarceration”

- Leslie, Emily and Nolan G. Pope. The Unintended Impact of Pretrial Detention on Case Outcomes: Evidence from New York City Arraignments

- “The Hidden Costs of Pretrial Detention” Lowenkamp, Christopher, Marie VanNostrand, and Alexander Holsinger

New York, New Jersey, and Philadelphia all increased their use of pretrial release without significant increases in crime or non-appearance rates:

- Aurelie Ouss and Megan T. Stevenson, “Evaluating the Impacts of Eliminating Prosecutorial Requests for Cash Bail

- New Jersey Judiciary, Report to the Governor and the Legislature

Aubrey Fox and Stephen Koppel Pretrial Release Without Money: New York City, 1987-2018

The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights outlined six principles that can mitigate the harms of risk assessments. For example, risk assessments should not recommend detention. Pretrial risk assessment instruments, if used at all, should only identify groups of people to be released immediately. Anyone deemed ineligible for immediate release should have an individualized pretrial release hearing as soon as possible. ↩

For more information on Washington, DC’s outcomes, see: Pretrial Services Agency for the District of Columbia’s Congressional Budget Request ↩

Due to racial profiling and the excessive policing of communities of color, people of color, especially Black Americans, are disproportionately impacted by fines and fees. This is especially damaging, as people of color tend to have lower levels of income and wealth compared to white people, and are therefore less likely to be able to pay fines and fees. ↩

While this legislation is a step in the right direction, Texas must take further action to reduce the number of people incarcerated for the inability to pay criminal justice debt. The legislation encourages judges to use alternatives to jail, but does not require it. Many judges still sentence people to jail time for unpaid fines and fees. In 2018, hundreds of thousands of people were still incarcerated for not paying fines and fees. ↩

The Vera Institute of Justice explains the risks to counties that depend on contract beds: “Jails confront similar financial incentives [to private prisons] when they are reimbursed for people they hold for other agencies, especially when they are under-resourced. And when the state and feds send fewer people, local taxpayers are on the hook for the budget shortfall, while the availability of more jail beds invites the specter of unnecessary pretrial detention.” ↩

After voters in Johnson County (Iowa City), Iowa,

After voters in Johnson County (Iowa City), Iowa,  In 2017, the Texas legislature passed a law that requires judges to “determine a defendant’s ability to pay fines and costs at sentencing, allows judges to waive or reduce fines and fees, and provides for sentencing alternatives when the defendant is unable to pay fines and fees, and it limits arrests and incarceration for inability to pay fines and fees.” As a result of this legislation, the number of people incarcerated for failure to pay fines

In 2017, the Texas legislature passed a law that requires judges to “determine a defendant’s ability to pay fines and costs at sentencing, allows judges to waive or reduce fines and fees, and provides for sentencing alternatives when the defendant is unable to pay fines and fees, and it limits arrests and incarceration for inability to pay fines and fees.” As a result of this legislation, the number of people incarcerated for failure to pay fines  In 2011, Seattle developed a

In 2011, Seattle developed a