The new resource uses data generated by New York’s law ending prison gerrymandering.

February 19, 2020

A new project from the Prison Policy Initiative maps where people in New York state prisons come from, down to the neighborhood level — providing a groundbreaking tool for studying how incarceration relates to community well-being.

The project, Mapping Disadvantage: The Geography of Incarceration in New York, provides anonymized residence data for everyone in New York state prisons at the time of the 2010 Census. Readers can download the data at several geographic levels, including counties, cities, and legislative districts.

“If you want to study how mass incarceration has impacted specific communities in New York, or how incarceration tracks with other indicators of community health, we’ve just published the geographic data you need to do that,” said Prison Policy Initiative Research Director Wendy Sawyer.

In a short report, produced in collaboration with VOCAL-NY, the Prison Policy Initiative provides examples of what can be done with the new dataset. The report shows that:

- In New York City neighborhoods with high rates of asthma among children, incarceration rates are also significantly higher.

- In city school districts, 5th grade math scores are very strongly correlated with neighborhood incarceration rates.

- Across the state of New York, every 1% increase in a particular Census tract’s unemployment rate is correlated with an uptick in the incarceration rate.

A landmark 2010 law made this mapping project possible. In 2010, New York passed a bill ensuring that people in prison would be counted as residents of their hometowns at redistricting time. This reform ended the electoral distortion known as “prison gerrymandering,” which had given extra political influence to the legislative districts that contained large prisons. The law required the state prison system to share its own records of where incarcerated people actually resided with redistricting officials. Using these records, redistricting officials produced a corrected dataset that they used to draw new district lines, and the Prison Policy Initiative repurposed this dataset for its report.

For the 2020 round of redistricting a total of seven states — California, Delaware, Maryland, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, and Washington — have passed legislation to end prison gerrymandering and nine additional states — Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Michigan, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, and Wisconsin — have legislation pending.

“These states are passing laws to end prison gerrymandering because they believe that everyone should have the same access to political power, regardless of whether they live next to a large prison. But these laws also have a secondary positive impact: they can make a deeper understanding of our criminal justice system possible,” said Executive Director Peter Wagner.

Prison systems have shown they are unprepared and unwilling to care for an aging prison population - whether by improving healthcare or expanding compassionate release.

by Emily Widra,

February 13, 2020

A newer article about state prison deaths with data from 2018 is now available. We suggest using that article instead of this one.

A new Bureau of Justice Statistics report released yesterday shows that from 2015 to 2016, the number of deaths in U.S. state prisons increased from 296 to 303 per 100,000 people. What accounts for these deaths?

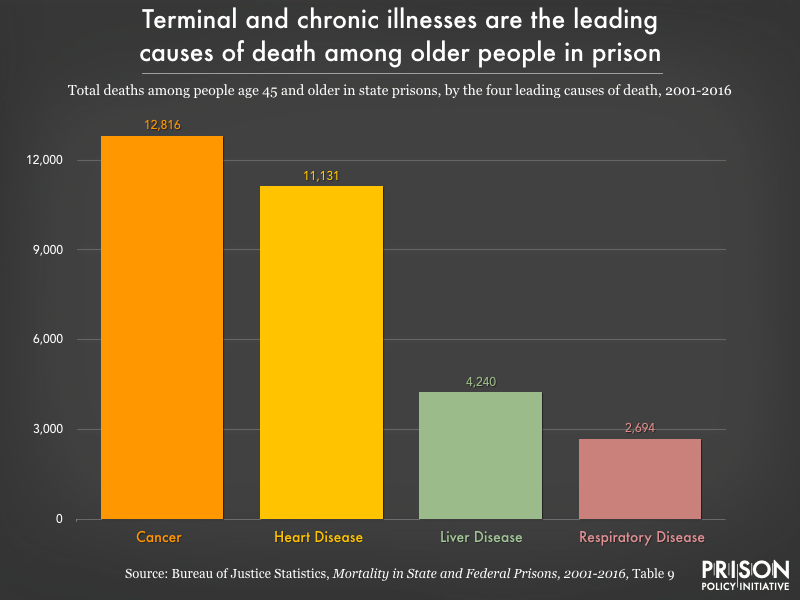

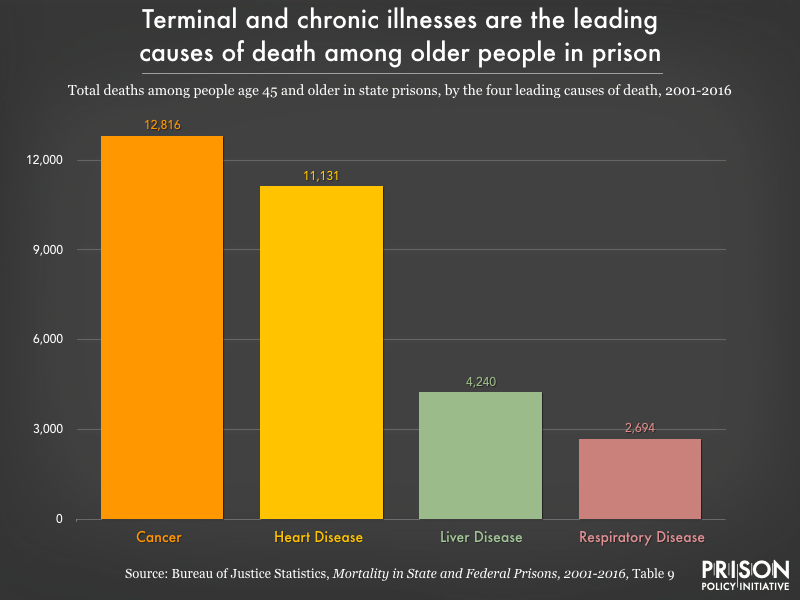

Chronic illnesses continue to be the leading cause of death in state prisons, according to the report — far outpacing drug- and alcohol-related deaths, accidents, suicides, and homicides combined. The number of deaths from chronic illness — including a growing number of deaths from cancer in prison, at a time when overall deaths from cancer are going down — is a testament to the extremely poor healthcare incarcerated people receive. It also highlights the ways that prisons are unable and unwilling to care for their elderly residents, who comprise a growing share of the prison population.

Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Mortality in State and Federal Prisons, 2001-2016 and Mortality in Local Jails and State Prisons, 2000-2013

Prison accelerates aging and increases the risk of early death from illness

As we’ve written about previously, each year of time served in prison takes two years off an individual’s life expectancy. Evidence suggests that the reason for this is that incarcerated people experience “accelerated physiological aging.” Prison ages incarcerated people by 10 to 15 years on average, which in turn makes them more vulnerable to chronic health conditions earlier in life than would be expected. As we see in the new prison mortality data, these chronic conditions – cancer, heart disease, liver disease, and respiratory diseases – are among the most frequent causes of death in state prisons.

Researchers have identified a number of reasons why prisons increase the risk of illness and early death (for a concise review, see Novisky 2018). These include, but are not limited to: varying degrees of health literacy and capital among incarcerated people; constraints on transportation to necessary appointments outside the prison; and inadequate healthcare in prisons due to insufficient resources, limited medical providers, restrictions on medication administration, and treatment bias because of stigmas attached to incarcerated patients. And – particularly for older or otherwise more vulnerable people – punitive practices like solitary confinement compound existing physical and mental health concerns and risks.

Prisons are not prepared for the health problems and mortality of their aging populations

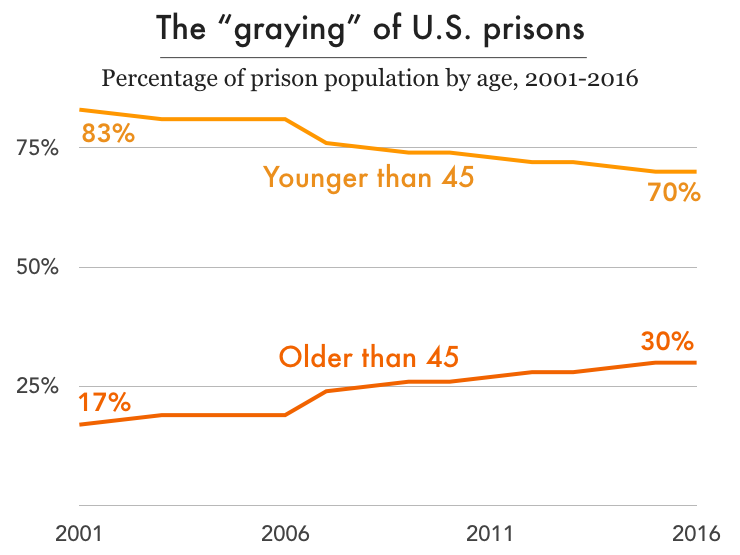

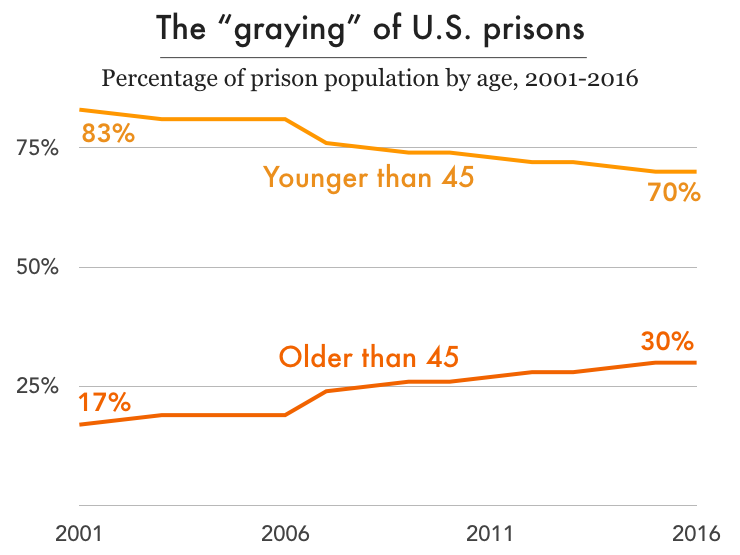

Nationally, the imprisonment rate for people over 45 years old has more than doubled over the past three decades while the rate for those under 45 has actually dropped slightly. Mortality has become an urgent issue in places like the Louisiana State Penitentiary (“Angola”), where the average age is over 40 and the average sentence is longer than 90 years. With thousands of aging adults facing the prospect of dying in prison in the coming years, how are prison systems preparing to handle the increased physical and psychological needs of the graying prison population? In short, they’re not preparing at all.

While the country incarcerates more older adults for longer sentences, prison systems have not adapted to the changing needs of the prison population. Despite examples of increased spending on prison healthcare, access to necessary healthcare remains inadequate. There are frequently lapses between prescription refills, as well as unmet dietary needs and unaffordable medical copays. We know that copays jeopardize the health of incarcerated populations, staff, and the public because when healthcare is unaffordable, sick people avoid the doctor, and diseases are likely to worsen and require more aggressive care. Yet most states still require copays to see medical staff behind bars. And even when incarcerated people do see medical staff, they face long waits: older adults in federal prisons wait an average of 114 days to see needed medical specialists in cardiology and pulmonology, which also puts them at risk for late diagnoses or no treatment at all.

Recent research from Prof. Meghan Novisky reveals how older incarcerated adults cope with the difficulties of accessing healthcare in prison. In her extensive qualitative study, Novisky finds that older incarcerated adults must rely on their networks – both in and outside of prison – and strategically use the limited resources available to them. Specifically, these older adults try to access health information from outside, from the prison library, and from other incarcerated people with medical backgrounds; they use the commissary and access to the kitchen to supplement the insufficient diet provided them; and they doggedly advocate for themselves with providers and through the grievance process, all in an effort to get their basic health needs met.

Beyond individual health outcomes, the financial burdens of the aging prison population can’t be overlooked: care for this population costs 2-3 times more than for their younger counterparts. The federal prison system reports spending 5 times more on medical care and 14 times more on medications per inmate in facilities with higher percentages of older inmates.

Bringing a measure of dignity to death in prison: Hospice programs

As the recent BJS report reminds us, mortality rates in prison are unlikely to slow, given the aging population and systemic healthcare problems. This reality begs the question: what does mortality behind bars actually look like for the people who are dying?

Currently, less than 4% of prisons have hospice programs. Most prisons and jails were not built with any consideration for the fact that they would house people dying of cancer, pulmonary diseases, liver failure, and dementia. But hospice has become one of the few humane attempts to address mortality in prison.

Hospice care involves a team of providers who care for people with life-limiting illnesses and their families with medical care, pain management, and emotional and spiritual support. The hospice model of care, based on a belief that every person has the right to die pain-free and with dignity, has made strides to fit into what Fleury-Steiner (2008) calls “the prison’s ‘natural environment’ of aggressive discipline and custody.”

“When speaking on end-of-life care, no one should be excluded. Dying with dignity is an essential component of our humanity and needs to be extended even into the shadows of our society.”

– Marvin Mutch, Human Prison Hospice Project

About half of these prison hospice programs use incarcerated people as volunteers or as employed (and underpaid) caregivers. They become a crucial part of the care team, given that medical staff are often spread thin and correctional officers don’t have the necessary training to provide end-of-life care. (Incarcerated volunteers who work in hospice do receive appropriate training.)

While having access to hospice care in prison is certainly better than dying there without such care, dying in prison is a bleak scenario no matter what. One hospice patient at the California Medical Facility expressed this succinctly to a New York Times journalist entering the hospice unit, greeting her with, “Welcome to death row.”

The alternative: Compassionate release

For terminally ill incarcerated people, the other option is compassionate release: the early release of individuals who are facing imminent death and do not pose a threat to the public. Compassionate release was created by Congress to release incarcerated people “when it becomes ‘inequitable’ to keep them in prison any longer.” This option allows incarcerated people to seek hospice care outside of prison, a chance for dignified death, and time with family. Moreover, it has the practical benefit of reducing medical costs to the state and federal government.

However, this more humane release mechanism is extraordinarily underutilized, for a number of bad reasons: narrow eligibility requirements, a burdensome application process, protracted hearings, third party veto power, a lack of formal timelines, reluctance of providers to provide a prognosis, lack of medial knowledge of parole board members, and no systematic procedures for tracking applications and decisions. According to The New York Times, between 2013 and 2017, the federal Bureau of Prisons approved only 6% of the 5,400 compassionate release applications received; meanwhile, 266 other applicants died in prison. Their analysis of federal prison data shows that it takes over six months, on average, for an incarcerated person to receive an answer on their compassionate release application from the BOP. In one tragic example, prison officials denied an application for someone because the BOP determined he had more than 18 months to live, despite prison doctors’ prognosis of less than six months. Two days after receiving the denial, he died. With a timeline like that, it is no wonder that the number of older adults dying behind bars continues to grow.

In 2016, over 1,000 people died in local jails - many the tragic result of healthcare and jail systems that fail to address serious health problems among the jail population, and of the trauma of incarceration itself.

by Alexi Jones,

February 13, 2020

A newer article about jail deaths with data from 2018 is now available. We suggest using that article instead of this one.

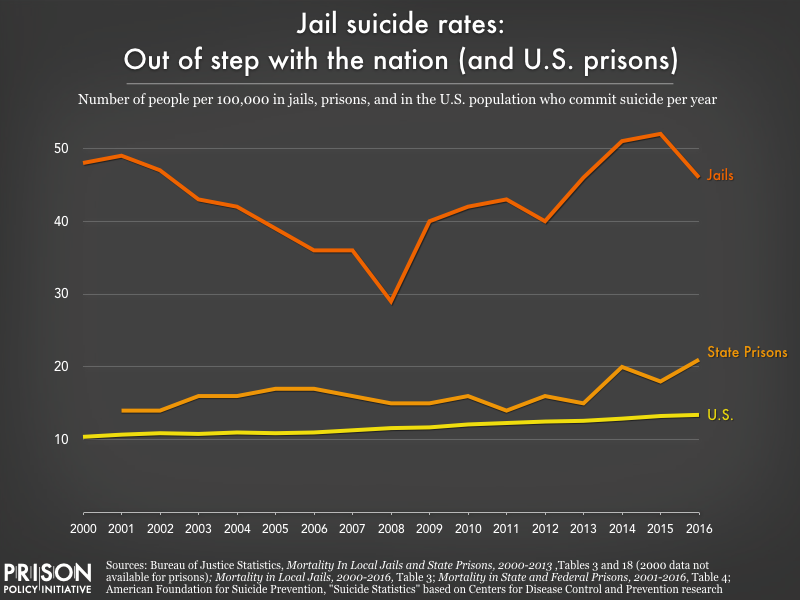

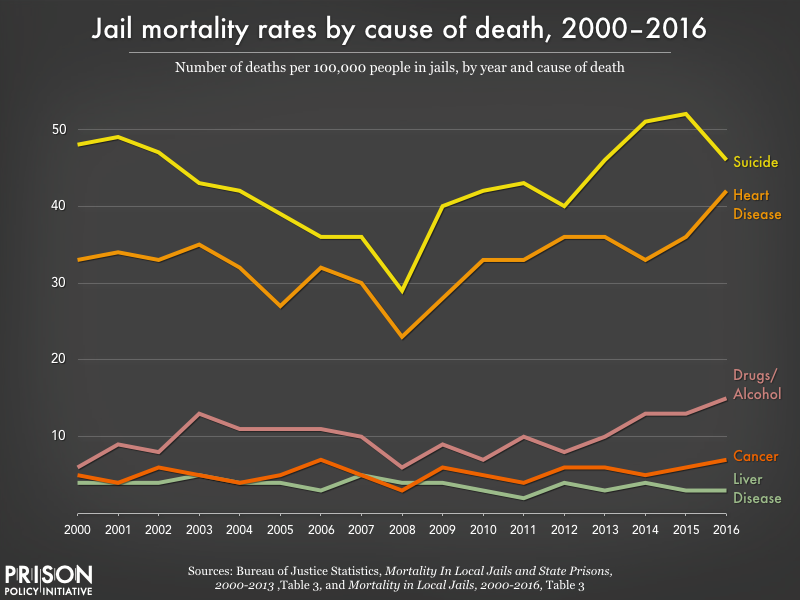

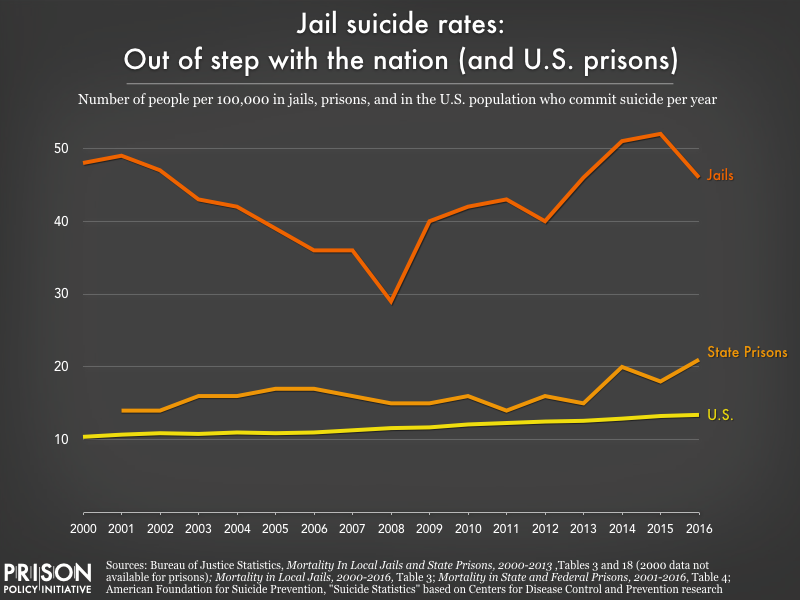

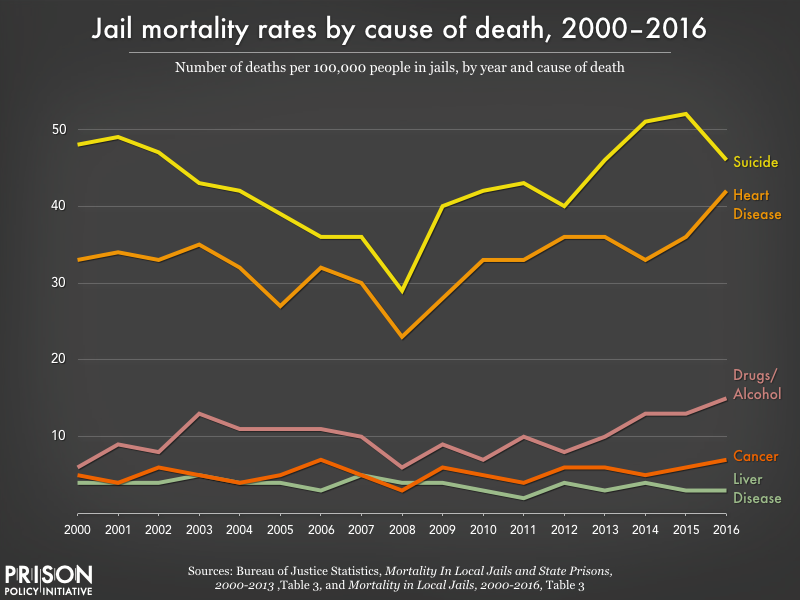

A new Bureau of Justice Statistics report reveals that over 1,000 people died in local jails in 2016, underscoring the dangers of jail incarceration. Most troublingly, the report finds at least half of these deaths are preventable, with suicide remaining the leading cause of death. These preventable deaths are the tragic result of healthcare and jail systems that fail to address serious health problems among the jail population – both inside and out of the jail setting – and of the trauma of incarceration itself.

The new report reveals that half of all deaths in jails are due to suicide, accident, homicide, and drug or alcohol intoxication, all of which are largely preventable. Once again, suicide was the leading cause of death in jails. The jail suicide rate is far higher than that of state prisons or among the American population in general.

The other half of deaths in jails are due to illness, such as heart disease or liver disease, many of which likely could have be prevented if not for the abysmal healthcare in jails.

People in jail often have serious physical and mental health needs. They are five times more likely than the general population to have a serious mental illness, and two-thirds have a substance use disorder. They also are more likely to have had chronic health conditions and infectious diseases. Moreover, many people experience serious medical and mental health crises after they are booked into jail, including withdrawal, psychological distress, and the “shock of confinement.”

Yet despite their serious needs, people in jail rarely have access to adequate healthcare. History has shown that jails are unable to provide effective mental health and medical care to incarcerated people.

For example, CNN recently published a scathing investigation into WellPath (formerly Correct Care Solutions), one of the country’s largest jail healthcare providers. The investigation found that WellPath provides substandard healthcare that has led to more than 70 preventable deaths in local jails between 2014 and 2018. WellPath, like other correctional healthcare companies, has been accused of prioritizing cost-cutting over patient health, with little governmental oversight. CNN found that WellPath doctors and nurses often denied specialized testing, medication, and treatments. They have also failed to diagnose and treat psychiatric disorders, denied emergency room transfers for urgent cases, and allowed common infections and conditions to progress to the point of fatality.

Previous research also shows that the jail environment itself can lead to serious health crises. As a report from the Department of Justice explains, “certain features of the jail environment enhance suicidal behavior: fear of the unknown, distrust of an authoritarian environment, perceived lack of control over the future, isolation from family and significant others, shame of incarceration, and perceived dehumanizing aspects of incarceration.” People in jails are regularly denied contact with family and friends through the elimination of in-person visits and the high cost of phone calls, denied access to adequate medical care and nutritious food, exposed to unbearable heat and cold, and often subjected to the torturous conditions of solitary confinement.

Moreover, jails are often understaffed and/or have inadequately trained staff, and the vast majority of people working in jails are trained as correctional officers, not health providers or social workers. Despite years of evidence that suicide is the leading cause of jail deaths, many jail staff are not even trained in suicide prevention. Worse, some jail staff display indifference toward incarcerated people’s lives, often refusing to take their health concerns seriously and cutting off access to healthcare – with fatal consequences. For example, Clackamas County Jail workers were caught on camera laughing and joking about a military veteran overdosing in his cell. Even a nurse on duty reportedly spent less than five minutes with the man, who died after authorities finally took him to a hospital.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics data released yesterday emphasizes, yet again, the dangers of even short jail stays: 40% of jail deaths occur within the first week of a person’s incarceration. Given how just a few hours or days in jail can turn deadly, the report underscores the need to divert people away from jail – especially those with mental health and substance use disorders who are at increased risk – as well as the urgency of reducing the use of pretrial detention.

Most "consumers" of telecom services in jails are families in poverty. Counties can and should negotiate contracts that treat them more fairly.

by Prison Policy Initiative,

February 7, 2020

The average cost of a phone call from a Texas county jail is 44 cents per minute1 — which can add up to hundreds of dollars a month for families trying to stay in touch — but Dallas County may soon lower its rates to 1 cent per minute. How? The county is aggressively renegotiating its contract with jail phone provider Securus, prioritizing getting the lowest rate possible for the families making the calls.

For other counties wondering how to negotiate contracts that treat consumers more fairly, we’ve just published three “best practices” guides. Our three guides cover the three most common types of telecommunications contracts in jails: contracts for phone services, contracts for video calling technology, and contracts for electronic tablets.

The simplest and best policy for a county is to pay for these services out of its general fund, thus making communication free. (Otherwise, personal wealth determines which families can stay in touch and which families can’t.)

For counties that won’t go that far, though, it’s still possible to write a jail contract that holds the vendor accountable, and allows families to stay in touch without paying dearly. Our best practices guides show how smart agencies can:

- Get the lowest rates possible for families by refusing commissions

- Protect customers from predatory fees, such as unnecessary “account maintenance” fees or high deposit fees.

- Make sure that vendors return customers’ unspent funds

- Ensure that expensive technology is never used to “replace” vital (and free) existing services

- Avoid excluding good providers from the bidding process by accident

During the contract award process, county procurement officials are often outmatched by their counterparts in the jail telecom industry — highly experienced businesspeople intent on maximizing their returns. Because of this imbalance, far too many poor families end up paying hundreds or thousands of dollars a month to stay in touch. But county governments that do their homework can get families a fairer deal.

To learn more, see our new best practices guides about:

And if you are new to these issues, see our research and advocacy about phone services in prisons and jails, protecting in-person visits from the video calling industry, and exploitation on prison tablets.

Footnotes