The prison context itself undermines public health and vaccination efforts

A new report from the Correctional Association of New York reveals why some people in prison are reluctant to get the COVID-19 vaccine and a lot of it has to do with distrust in the correctional system.

by Emily Widra, March 9, 2022

Over 3,000 incarcerated and detained people in the United States have died of COVID-19 in the past two years, with over 588,000 cumulative cases behind bars. With little sign of COVID-19 quietly fading away, public health officials have been clear, consistent, and accurate that vaccinations are our strongest defense against existing and future variants of COVID-19. But despite widespread vaccine availability across the country, many people continue to be hesitant about the COVID-19 vaccination.1

While the vaccine refusal rates are not generally worse in prisons than in the general population, vaccination is even more critical in prisons. Incarcerated people can’t employ other strategies to avoid getting COVID-19, they have higher rates of medical conditions that make them more vulnerable to severe illness and death, and if they do fall ill, they don’t have the same access to prompt, effective medical care as people outside of prison do. Behind bars, the risks of non-vaccination can be even more deadly, with a COVID-19 death rate of more than double that of the general U.S. population.2

An insightful new report from the Correctional Association of New York offers the only survey data we know of that explains why incarcerated people are hesitant to accept the COVID-19 vaccination. 3 A report focusing on New York is particularly valuable nationally because New York State was one of the least successful states (by our data 4) at vaccinating incarcerated people.5 The report finds that vaccine hesitancy in prison is rooted in general distrust and suspicion of healthcare in prison, and that the solutions to overcome vaccine hesitancy behind bars are more complicated than in non-carceral settings.

Researchers have determined that the best practice for addressing vaccine hesitancy – in general and in the context of COVID-19 – is to promote transparency, equity, and trust between individuals, communities, and healthcare providers.6 In addition, we know that community engagement,7 messaging and education,8 and timely and accurate information about vaccines are critical for responses to vaccine hesitancy.

The reality is that the prison context inherently undermines almost all of the best practices for responding to vaccine hesitancy.

The erosion of trust in prison healthcare undermines vaccination efforts

The major finding of the Correctional Association report is that the primary reason people behind bars are hesitant to get the vaccine is a lack of trust in the prison medical system.

Before COVID-19, incarcerated people were suspicious and critical of prison healthcare: they reported poor quality of care, difficulty accessing medical care, and a distrust of prison medical care. Some incarcerated people in New York cited the Tuskegee syphilis experiment and the water crisis in Flint, Michigan as reasons to be suspicious of state public health initiatives, stating, “My greatest fear is to be a lab rat for the state” and “Communities of color have always been experimented on; why are state officials going to stop now?”

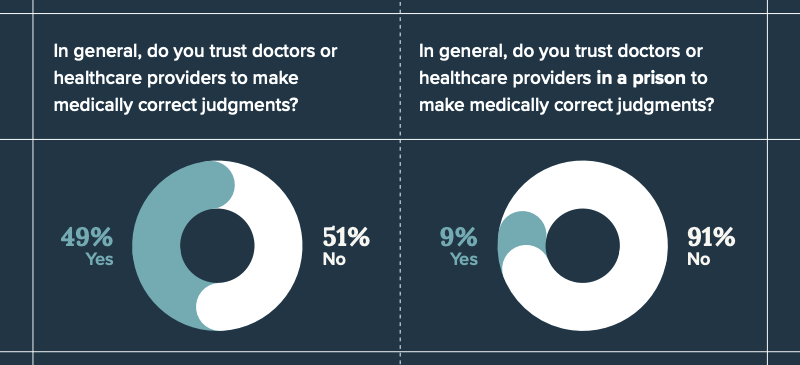

But the distrust is particularly poignant in the context of COVID-19 vaccinations. A slight majority of incarcerated people surveyed by the Correctional Association reported that they generally “trust vaccines” (52%). A similar number (49%) of respondents reported that they generally trust doctors and healthcare providers to make medically correct judgements, but only 9% of respondents trust doctors or healthcare providers in a prison to make medically correct judgments.

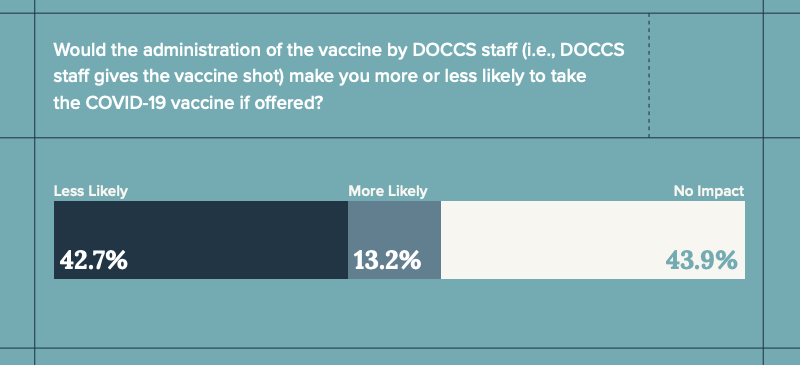

Given that general distrust of prison medical providers, it’s unsurprising that a significant portion of survey respondents were less likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccination if offered by the New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision’s (DOCCS) medical staff.

“What works” to overcome vaccine hesitancy hasn’t worked in prisons

Public health experts have established best practices for addressing vaccine hesitancy, but the persistence of this distrust among incarcerated people underscores how the prison setting itself undermines these practices:

- Trusted communicators are crucial to expanding vaccine acceptance. Most recommendations for addressing vaccine hesitancy emphasize the need for “trusted communicators,” but with limited visitation and suspended programming and volunteers, who are the trusted communicators in prisons? The reality is that most information about the vaccines in prisons comes from prison administrators and correctional staff. In May 2021, a month after vaccines were available to people in congregate living situations (like prisons), John J. Lennon (incarcerated in New York) recommended in a New York Times op-ed that the DOCCS “tap influential prisoners to disseminate accurate vaccine information” and even suggested utilizing the preexisting inmate liaison committees established after the Attica uprising. According to the recent Correctional Association report, the New York DOCCS instead “developed a video featuring Tyler Perry and incarcerated people attesting to the benefits of the vaccine.” The reality is that trust, transparency, and equity have long been eroded by the criminal legal and prison systems, which this video had little hope of repairing.

- Community engagement is often limited in prisons, where interactions between incarcerated people are regularly restricted. During COVID-19, community engagement behind bars all but disappeared. Programming – including education courses, work-release, treatment programs, and group activities – were suspended in every state prison system (as far as we’ve been able to tell) at some point during COVID-19. Many prisons stopped programming and in-person visits entirely for the better part of the past two years. Additionally, incarcerated people have experienced unnecessary use of solitary confinement during the pandemic. Correctional institutions in the United States have long been distanced from “mainstream” society and community, and in many ways, the pandemic has only furthered that isolation. So while having community members and volunteers who aren’t part of the prison system come in to informally discuss vaccination concerns might have helped improve vaccine acceptance, incarcerated people saw even fewer people from the outside during the pandemic.

- Disseminating timely and accurate information has proven difficult in correctional facilities. Contact with those outside prison walls has been limited throughout the pandemic, with suspended or limited visitation, increasing restrictions on mail, expensive phone calls, and interrupted programming. But relying on information from only within the prison comes with a high cost for vaccine acceptance: misinformation and distrust of the vaccine can run rampant and unchecked. John J. Lennon reported for the New York Times that corrections officers where he is incarcerated told him that the vaccine was “not tested enough” and that COVID-19 was just “the flu.” A sergeant in the Florida Department of Corrections told The Marshall Project, “If I’m wearing a mask, gloves, washing my hands and being careful — I’d still feel better working like that than putting the vaccine in my body.” Other correctional officials in Florida told The Marshall Project that some of their colleagues believe the vaccine could give them the virus or that the vaccine contains some kind of tracking device.9

The responses to the Correctional Association survey point to a lack of trust in prison medical care providers based on the quality and inaccessibility of care, limited access to information about their healthcare, and the tension between healthcare professionals meeting their duty to their patients while enforcing and complying with directives of the prison administration (sometimes referred to as “dual loyalty“). The DOCCS’ mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent traumatic experiences during COVID-19 in prison, only served to erode incarcerated people’s trust further.

In many ways, the pandemic has served to highlight just how opaque the prison healthcare system is and just how wary incarcerated people are of prison medical care. Moving forward, prison systems must do better, not only by providing better, more accessible, more transparent health care, but also by recognizing their inherent limits when it comes to responding to public health concerns, and adopting better strategies.

Specifically, when faced with the current and future health emergencies, prison systems should:

- Release more people from prisons. Nationwide, states and the federal government actually released 10% fewer people from prison in 2020 than in 2019, despite the consensus among public health officials and advocates that decarceration is crucial to protecting public health and limiting the spread of COVID-19. To reverse this trend, departments of corrections, state governments, and courts need to work together to release people from prison using any tools they have at their disposal, including large-scale releases like we saw in New Jersey, California, and North Carolina. The Correctional Association report recommends increasing the use of pretrial release, alternative sentencing, early release, medical parole, parole board release, and commutation to rapidly reduce prison populations.

- Address issues of transparency and equity in correctional health care. To address these issues in the context of COVID-19, the Correctional Association report recommends expanding the provision of adequate and timely information about COVID-19 and the vaccine, and alleviating gaps in the quality of medical services by expanding preventative care (routine screenings, education, and outreach). To improve general correctional healthcare, the Correctional Association report recommends that the state designate an independent correctional ombuds to investigate and resolve complaints related to incarcerated peoples’ health, safety, welfare, and rights, as well shift oversight of correctional healthcare to the state department of health.

- Ensure that corrections officials are dedicated to reducing our reliance on incarceration and improving the health and welfare of those under their care. Corrections officials and decision makers need to take COVID-19 – and the subsequent deaths of over 3,000 incarcerated people – seriously. Incarcerated people’s connection to up-to-date news is tenuous at best, and during COVID-19 (with limited visits and changes in phone call and mail policies), they’ve been even more reliant on information directly from corrections departments. Mixed messages about the realities of COVID-19 from corrections departments (we’ve heard at least one report of a PA system announcement in a Pennsylvania prison facility stating that the pandemic is “over”) and corrections officers’ own vaccine hesitancy and misinformation leave incarcerated people in the dark to the detriment of everyone.

While COVID-19 vaccinations and booster doses are some of our strongest defenses in the face of the continued pandemic and new variants, it’s increasingly clear that prison systems need to prioritize decarceration. No amount of public health education and vaccine messaging will, on their own, dismantle decades of distrust and suspicion of prison health care. Prisons are no place for a public health crisis and government officials should be prioritizing releases and decarceration as both a first response and an ongoing response to emergencies like COVID-19.

Footnotes

-

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines “vaccine hesitancy” as a “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine service” and in 2019 – before COVID-19 – vaccine hesitancy was one of the ten greatest risks to global health. ↩

-

The COVID-19 death rate in prisons at the end of April 2021 stood at a staggering 200 deaths per 100,000 incarcerated people, much higher than the death rate among the general U.S. population of 81 deaths per 100,000 residents. These rates, calculated by the UCLA Law COVID Behind Bars Data Project, were adjusted to account for differences in age and sex between the prison population and the general U.S. population. For more details about how these rates were calculated, see “COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality in Federal and State Prisons Compared With the US Population, April 5, 2020, to April 3, 2021” published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. ↩

-

Although it is outside the scope of the Correctional Association report and this briefing, it is important to mention that there are still instances of incarcerated and detained people requesting COVID-19 vaccines and/or boosters and being denied. For example, a 2022 lawsuit filed by the ACLU on behalf of people detained in ICE facilities reported that detainees had been repeatedly denied booster doses despite obvious medical vulnerabilities. ↩

-

Comparative data on vaccination in prisons is very hard to come by as many states do not publish the data, do not publish it frequently, or calculate it differently. But as of our December 2021 survey, New York had one of the lowest rates – 52% as of December 5, 2021 – and almost all of the states with lower rates of vaccination had much older data, dating as far back as June 2021 when the vaccine itself was in short supply. (The Correctional Association reports a figure of 48.3% as of September 2021, which they presumably received directly from the state prison system.) ↩

-

New York’s vaccination plan implied that incarcerated people would be eligible early, with “those living in other congregate settings.” However, as of early March 2021, vaccine eligibility had not yet been expanded to all incarcerated people. Availability to people younger than 65 in prison was made possible by a late March 2021 New York State Supreme Court ruling, after which the New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision began the vaccine rollout to the entire incarcerated adult population. The ruling noted that incarcerated people had been arbitrarily and unfairly excluded from the vaccine rollout plan: state officials “irrationally distinguished between incarcerated people and people living in every other type of adult congregate facility, at great risk to incarcerated people’s lives during this pandemic.” ↩

-

“Public Trust and Willingness to Vaccinate Against COVID-19 in the US From October 14, 2020, to March 29, 2021,” Journal of the American Medical Association (2021); “Strategies to Address COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Mitigate Health Disparities in Minority Populations,” Frontiers in Public Health, (2021); “Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom,” Nature Communications (2021); “Understanding COVID-19 misinformation and vaccine hesitancy in context: Findings from a qualitative study involving citizens in Bradford, UK,” Health Expectations (2021); “Racial differences in institutional trust and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and refusal,” BMC Public Health (2021); “Influences on Attitudes Regarding Potential COVID-19 Vaccination in the United States,” Vaccines (2020). ↩

-

“Strategies to Address COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Mitigate Health Disparities in Minority Populations,” Frontiers in Public Health (2021); “Building Vaccine Confidence Through Community Engagement,” American Psychological Association (2020); “The COVID-19 vaccines rush: participatory community engagement matters more than ever,” The Lancet (2021); “Strategies for public engagement to combat mistrust and build COVID-19 vaccine confidence,” The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2021). ↩

-

“Impact of an Education Intervention on COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in a Military Base Population,” Military Medicine (2021); “These are the pro-vaccine messages people want to hear” The Washington Post (2021); “Effects of different types of written vaccination information on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK,” The Lancet Public Health (2021). ↩

-

COVID-19 is not the same as the seasonal flu, the COVID-19 vaccines and boosters do not give you COVID-19, and the vaccines do not contain any tracking devices. ↩