Can you support our COVID-19 response work today? Donate

States of emergency: The failure of prison system responses to COVID-19

by Tiana Herring and Maanas Sharma

September 1, 2021

From the beginning of the pandemic, it was clear that densely packed prisons and jails — the result of decades of mass incarceration in the U.S. — presented dangerous conditions for the transmission of COVID-19. More than a year later, the virus has claimed more than 2,700 lives behind bars and infected 1 out of every 3 people in prison.

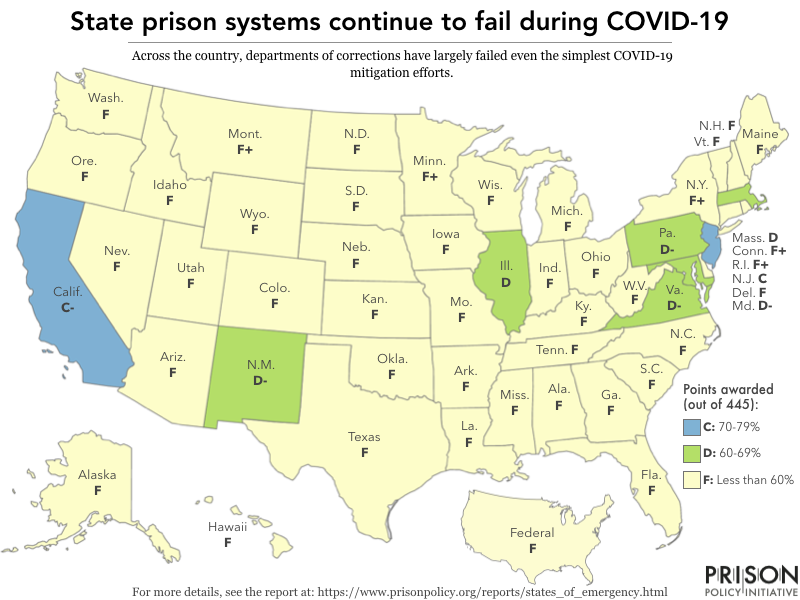

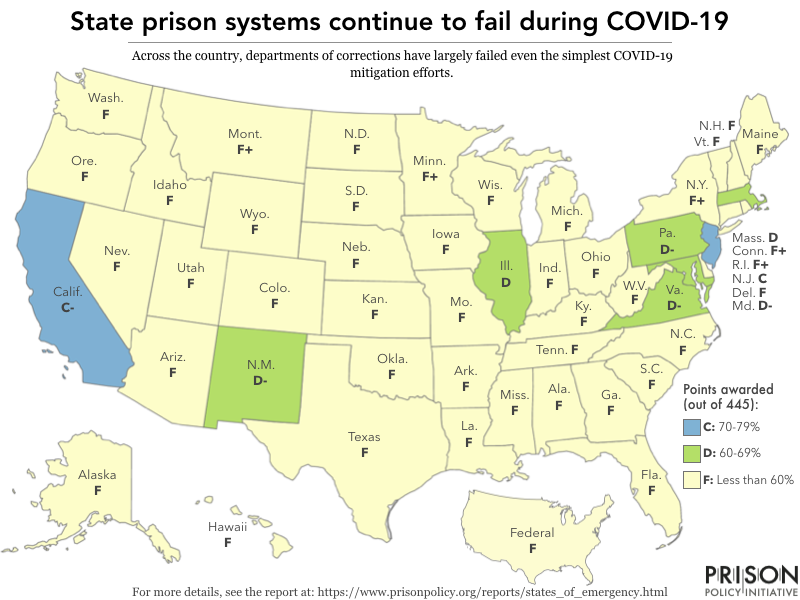

A year after we first graded state responses to COVID-19 in prisons, most state departments of corrections and the federal Bureau of Prisons are still failing on even the simplest measures of mitigation.

In this report, we evaluated departments of corrections on their responses to the pandemic from the beginning of the pandemic to July 2021. We looked at a range of efforts to:

- Limit the number of people in prisons: States received points for reducing prison populations1 as well as for instituting policies that reduced admissions and facilitated earlier releases.

- Reduce infection and death rates behind bars: We penalized prison systems where infection and mortality rates exceeded the statewide COVID-19 infection and mortality rates,2 because some key decisions were based on correctional agencies’ faulty logic that prisons were controlled environments and therefore better positioned to stop the spread of infection than communities outside prison walls.3

- Vaccinate the incarcerated population: States were rated higher for including incarcerated people in their vaccine rollout plans, as well as for higher vaccination rates among their prison populations.

- Address basic health (and mental health) needs through easy policy changes:4 We credited states for waiving or substantially reducing charges for video and phone calls,5 or providing masks and hygiene products to incarcerated people. States also received points for suspending medical co-pays (which can discourage people from seeking treatment), requiring staff to wear masks, and implementing regular staff COVID-19 testing.

While some states performed well on one or two of these criteria, no state’s response to COVID-19 in prison has been sufficient. The highest letter grade awarded was a “C”, and most states completely failed to protect incarcerated people:

New Jersey was rated higher than any other prison system in the U.S. — scoring a “C” grade — largely for vaccinating 89% of incarcerated people in the state. Additionally, New Jersey reduced prison populations by 42%, in part due to a large-scale release that allowed over 2,000 people to leave prison and return home.6 Similarly, California received a comparatively high “C-” grade for widespread vaccination efforts, providing some free phone calls, free video calls, and free hygiene products to incarcerated people, as well as eliminating medical co-pays prior to COVID-19.

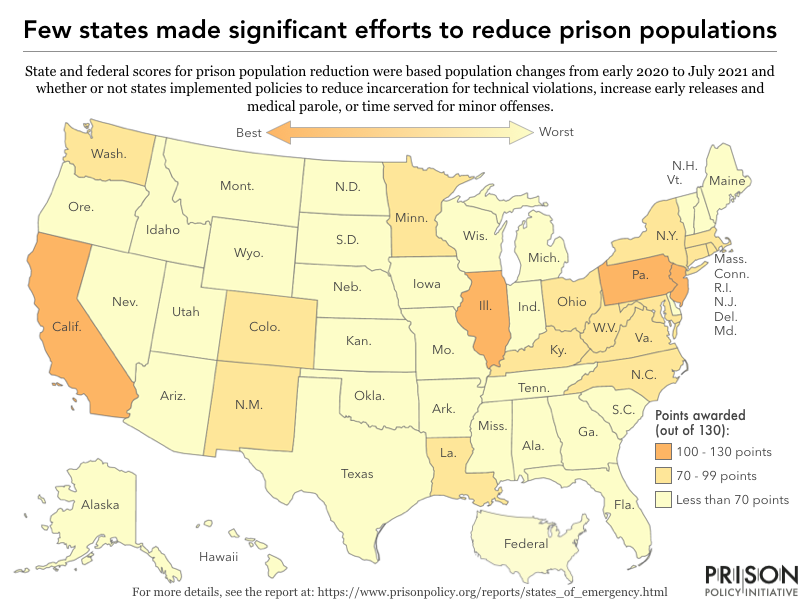

It’s telling that not one prison system in the U.S. scored higher than a C; as a whole, the nation’s response to the pandemic behind bars has been a shameful failure. Even New Jersey and California, which scored higher than the other 49 prison systems, did not do enough to mitigate COVID-19. In New Jersey, the infection rate (42%) in prisons was 3.8 times higher than the statewide COVID-19 infection rate (11%), and the COVID-19 mortality rate in prisons (0.48%) was almost double that of the statewide COVID-19 mortality rate (0.28%).7 Rates of COVID-19 infection and mortality in California were similarly high compared to the statewide rates, dropping the state’s scores. And while California reduced its prison populations by much more than other states (cutting it by 19%), it was still not enough to end the rampant prison overcrowding across the state, leaving thousands of incarcerated people vulnerable to infection. In June 2021, California state prisons were still holding more people than they were designed for, at 107% of their design capacity (and up from 103% in January 2021).

While all of the composite scores were dishearteningly low, some states performed well by certain measures:

- After New Jersey, Connecticut and Illinois reduced their prison populations most dramatically (dropping by 27% and 26%, respectively).

- Some states that conducted mass testing, such as Missouri and Wisconsin, reported higher infection rates, but lower mortality rates. Other states like Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama had low reported infection rates, but that is potentially attributable to abysmal testing practices leading to potential undercounting.8

- North Dakota, New Jersey, and Oregon9 all scored exceptionally high for vaccinations, with rates above 85%.

- California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, and Montana all received full points for adopting a wide range of easy policy changes to address basic health needs. Only one state—Nevada—did not institute any changes to their medical copay policies, leaving incarcerated people to pay for health services.

We gave most states failing grades because they refused to address basic health (and mental health) needs for those trapped inside and they shied away from releasing large numbers of people who could have been safely returned home, all of which contributed to extremely dangerous conditions behind bars:

COVID-19 response in New Jersey

See details about the COVID-19 response in

Conclusions

Publishing publicly available data on cases, testing, vaccines, and deaths allows the public to see that departments of corrections are tracking the virus, which is the first step to addressing the crisis behind bars.10 Without knowing the status of COVID-19 in their facilities, there is no way for prison systems to be addressing the crisis. Additionally, families rely on information from departments of correction about how their loved ones are faring. During the pandemic, with visitation suspended across the country, families are even more reliant on information from prison officials about the status of COVID-19 in particular facilities. Despite the critical nature of COVID-19 data, the vast majority of states are failing to release comprehensive data, and many are no longer updating the data dashboards on their websites. And two states — Arkansas and Rhode Island — were not willing to provide us with updated vaccination numbers for this report.11

Since prisons barely protect the lives of incarcerated people during normal times, it’s no wonder they have not been able to manage an emergency. Many prisons do not have adequate emergency response plans, limiting their ability to swiftly enact meaningful changes that could save lives. It’s imperative that prisons develop detailed emergency response plans that address how they will handle various situations, from pandemics to natural disasters.

Finally, it’s worth noting that there have been some positive changes in policies and practices that should be preserved long after the pandemic. Many departments of corrections suspended medical co-pays during the pandemic, a policy which should be made permanent for the health of incarcerated people. States should also provide phone and video calls, as well as hygiene products, to incarcerated people free of charge for their physical and emotional wellbeing.

Most importantly, reducing prison populations should be a top priority for states after the pandemic is over. Changes in law and policy over the past 40+ years have resulted in the U.S. incarcerating people — particularly Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people — at excessively high rates. Further, prison overcrowding has been linked to problems like increased violence, lack of adequate health care, limited programming and educational opportunities, and reduced visitation. As states continue to address the pandemic, allowing prison populations to creep back up to their unjust, unsustainable prior levels should not be part of the return to “normalcy.”

Methodology & scoring

Composite scores

We scored state prison systems and the federal Bureau of Prisons on almost 30 data points and 16 factors to measure their response to the COVID-19 pandemic, with a maximum possible score of 445 points. We converted each system’s final score to a percentage of the maximum score, and then to a standard letter grade scale. Given the number of states that received a failing grade, we created the non-traditional grade of an “F+” to distinguish the few states that fell just a few points short of earning a “D-” from the other states whose failures showed a consistent lack of effort.

What we considered

The criteria used to score these prison systems can best be understood in four main categories:

- Population reduction: The prison system reduced the incarcerated population and implemented policies suspending incarceration for technical parole and probation violations, instituting accelerated release programs, expanding compassionate release or medical parole programs, and allowing the release of those with lower-level offenses. (maximum 130 points) ⤵

- Infection and death rates: The prison system’s COVID-19 infection rate and death rate were equivalent to or less than the statewide rates. (maximum 145 points) ⤵

- Vaccination efforts: Incarcerated people were prioritized in vaccine distribution plans and at least 70% of the prison population had received at least one dose of the vaccine. (maximum 115 points) ⤵

- Basic policy changes to address health needs: The prison system provided incarcerated people with free phone and video calls, masks, and hygiene products (like soap), required masks for staff and mandated regular staff testing, and eliminated medical co-pays. (maximum 115 points) ⤵

We awarded points to states based on the information they had published publicly. If policies — such as COVID-19 testing requirements or accelerated prison releases — weren’t made public, we did not award points for them.

We did this mainly for expediency’s sake: Sending FOIAs or making phone calls about all of these issues to all state departments of corrections would have taken too long. But in addition, we wanted to hold states to an appropriate standard of transparency. By having certain policies — such as mask mandates for prison staff — but not sharing them with the public, states can avoid having to be accountable when those policies aren’t followed. This kind of obscurity also hurts families of incarcerated people who are trying to figure out what safety measures are in place to protect their loved ones. In any year, but particularly a pandemic year, transparency is important.

Population reduction (130 points)

The U.S. incarcerates more of our population per capita than any other country in the world. Before the pandemic, 9 state prison systems and the federal prison system held more people than they were designed to, and despite some pandemic decarceration efforts, there were still 9 states and the federal prison system that continued to operate at over 100% of their capacity in late 2020. Research conducted in Massachusetts and Texas prison systems shows that the COVID-19 infection rate was significantly higher in prisons operating at a higher percentage of their design capacity than those with less crowded populations and more single-person cells available. Given that every increase of 10 percentage points in population relative to the prison’s design capacity raised the risk of COVID infection by 14 percent, decarceration remains a moral and public health imperative.

There are two major ways to reduce prison populations: increasing releases and reducing admissions. However, simply limiting prison admissions is not the most efficient way to reduce the incarcerated population, and can lead to increased jail overcrowding if people who have been sentenced are not able to transfer from jail to prison. We awarded points according to the percent change in prison populations from March 2020 to June 2021,12 plus additional points when states implemented explicit policies for the release of more people. For each one percent reduction of the prison population, states were awarded 2 points, up to a maximum of 60 points.13 We also awarded points for four potential avenues of increasing prison releases: suspending incarceration for technical parole and probation violations (20 points); instituting accelerated release programs (15 points); expanding compassionate release or medical parole programs (15 points); and allowing the release of those with lower-level offenses (20 points).14

Population reduction scoring (130 points)

| Policies to reduce population | Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy to reduce incarceration for technical violations of probation and parole | Policy to accelerate releases | Policy to increase use of medical and/or compassionate release | Policy to release of people imprisoned for “minor” offenses | Actual population reduction | |

| Points possible | 20 points | 15 points | 15 points | 20 points | 2 points for every 1% reduction in population (maximum 60 points) |

Infections & deaths (145 points)

While most of the other measures in this scorecard were based on the adoption of policies and the overall population change, the 145 points in this category were awarded for the actual performance of prison systems: infection and mortality rates behind bars.

We evaluated the ability of prison systems to keep infection rates and mortality rates lower than that of their state as a whole. (For the Federal Bureau of Prisons, we compared that system to the nation as a whole.) To do so, we first calculated the rates of infection and death from COVID-19 in each prison system, using the most recent number of positive cases, deaths, and population as of June 2021. To compare these rates with statewide and national rates, we then calculated the overall infection and death rates for each state and the entire country, which is available in Appendix Table 3.

For scoring, states that kept their infection rates inside of prisons equal to that of their state as a whole received 75 points; similarly, states that kept mortality rates inside of prisons equal to the state’s overall mortality rate received 30 points. Prison systems that managed to do better than their state did overall received more points, up to a maximum of 105 points for infections and up to a maximum of 40 points for mortality. Prison systems that did worse managing COVID-19 than their state as a whole received fewer points. Despite this generous scoring system, 23 states received zero points for their infection rates—reflecting infection rates that were more than 3 times higher than the general rate.

Infections and deaths scoring (145 points)

| Equal rates in prisons and statewide | Higher rates in prisons than statewide | Lower rates in prisons than statewide | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID‑19 infection rate | COVID‑19 mortality rate | COVID‑19 infection rate | COVID‑19 mortality rate | COVID‑19 infection rate | COVID‑19 mortality rate | |

| Points possible | 75 points | 30 points | Subtracted 1 point from 75 points per 1% increase in infection rate (minimum of 0 points) | Subtracted 1 point from 30 points per 1% increase in mortality rate (minimum of 0 points) | Added 1 point to 75 points per 1% decrease in infection rate (maximum of 105 points) | Added 1 point to 30 points per 1% decrease in infection rate (maximum of 40 points) |

Vaccination efforts (85 points)

Once vaccinations were no longer in short supply nationally, we expected all states—even those that did not prioritize incarcerated people for vaccination—to quickly succeed at vaccinating large portions of their prison populations. Unfortunately, most states fell far short of this essential milestone and their scores reflect it.

We synthesized multiple data sources and our own requests for information to collect the priority level of incarcerated people in each state’s vaccine rollout, as well as the percentage of incarcerated people in each state who had been vaccinated. To measure vaccination, we used the number of people who had received at least one dose, since this was the most universally available measure; other measures, like full vaccinations, were more complicated and not reported universally.

If all incarcerated people were of the highest priority in the state’s vaccination rollout plans, the state earned 25 points. If only medically vulnerable people in prisons were in the highest priority or if all incarcerated people were of a medium priority, 10 points were awarded. All others received 0 points. For vaccinations among incarcerated people, states received 1.5 points per percent vaccinated from 50% to 70%, representing 30 total available points15 An additional 2 points per percent vaccinated from 70% to 90% was awarded on top of that. All but seven states had vaccinated more than 50% of their incarcerated populations and almost 30 states had vaccinated more than 70% of their prison populations as of July 1, 2021, earning extra points.

Vaccinations scoring (115 points)

| Vaccination plans | Vaccination rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incarcerated people included in the highest priority category | Incarcerated people included in the highest priority category only if medically vulnerable or included in the second or third priority category | Incarcerated people included in the lowest priority category or not at all | 0-50% of incarcerated population vaccinated | 50-70% of incarcerated population vaccinated | 70-90% of incarcerated population vaccinated | ||

| Points possible | 25 points | 10 points | 0 points | 0 points | 1.5 points per 1% of population vaccinated (maximum 30 points) | In addition to the points for having up to 70% vaccinated, 2 points were per 1% population vaccinated over 70% | |

Basic policy changes to address health (and mental health) needs (115 points)

COVID-19 spreads rapidly and easily in prisons, especially given that prior to the pandemic, nine state prison systems and the BOP were housing more people than they were designed to. Therefore, we heavily weighed whether or not carceral agencies were doing the bare minimum for protecting the health of incarcerated people. If incarcerated people are not provided masks or if staff PPE (masks, face shields, etc.) is not mandatory in prisons, we deducted 20 points. Prisons are notoriously unhygienic places where incarcerated people must often spend what little money they have on hygiene products like soap. States that made changes to provide free and easily accessible hygiene products (like hand sanitizer, soap, etc.) in prisons were awarded 15 points. An additional 40 points were rewarded for policies mandating regular staff testing. Our scoring system did not differentiate between staff testing intervals. States requiring staff COVID-19 testing daily, weekly, biweekly, monthly, or at any other interval received the maximum number of points. Given the wide availability of COVID-19 testing at this point in the pandemic, every state should have easily received the maximum number of points. Despite the need for correctional staff to be tested and vaccinated to protect both themselves and the incarcerated population, only 24 states received the maximum number of points for regular staff testing.

In this category, we also prioritized policies that maintain the dignity of incarcerated people and their loved ones. Medical co-pays deter incarcerated people from seeking medical attention—due to the outrageous costs of medical care behind bars relative to wages—and delayed medical care due to co-pays during a viral pandemic is unquestionably dangerous. 30 points were awarded to states that suspended co-pays for the majority of the pandemic (e.g. suspension began in March, April, May, or June 2020 and has not yet been reinstated), 15 points for initiating co-pay suspensions after June 2020 or reinstating co-pays that were previously suspended, and 0 points for states that made no change and continued to charge copays as usual. States that eliminated co-pays before the pandemic were given the full 30 points. Given the widespread cancellation of in-person visitation to reduce the spread of COVID-19, we awarded 15 points each (for a total of 30 possible points) for making video calling free and phone calls free—an important move for the emotional well-being of both those inside the prison and their loved ones.

Basic policies scoring (115 points)

| Provided masks to incarcerated people | Provided free hygiene products (like soap or hand sanitizer) | Free video calls | Free phone calls | Suspension of medical co-pays | Required staff to wear masks | Mandatory and regular staff testing | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete elimination of medical co-pays | Suspension of medical co-pays in March, April, May, or June 2020 without reinstating co-pays | Suspension of medical co-pays began after June 2020 or co-pays have been reinstated | No changes to policy and continue to charge medical co-pays | ||||||||||||||

| Points possible | Deducted 20 points for not providing masks | 15 points | 15 points | 15 points | 30 points | 30 points | 15 points | 0 points | Deducted 20 points for not requiring | 40 points | |||||||

Letter grades

To calculate the final composite score, we added the total number of points that each prison system received and divided that by the total possible points (445) to calculate the percentage. From there, we assigned letter grades based on the following scale, which includes an “F+” grade as a way to distinguish those states that fell just short of a “D” but who tried considerably harder than the states that did far worse:

| Letter grade | Percentage |

|---|---|

| A+ | 97 - 100 |

| A | 93 - 96.9 |

| A- | 90 - 92.9 |

| B+ | 87 - 89.9 |

| B | 83 - 86.9 |

| B- | 80 - 82.9 |

| C+ | 77 - 79.9 |

| C | 73 - 76.9 |

| C- | 70 - 72.9 |

| D+ | 67 - 69.9 |

| D | 63 - 66.9 |

| D- | 60 - 62.9 |

| F+ | 57 - 59.9 |

| F | 56.9 or below |

Appendices

Appendix Table 1: Final letter grades and scoring

This appendix table presents the final composite score, percent of total points available, and a letter grade for each state based on their performance across four main categories during the pandemic. See Appendix Table 2 for a detailed breakdown of population reduction scores and data sources for population change; Appendix Table 3 for infection and death rates, scoring, and data sources on infections and mortality; Appendix Table 4 for data on vaccinations and sources for vaccine data; and Appendix Table 5 for a breakdown of basic policy changes to protect the health incarcerated people, how we scored them, and where we looked for the data. There is also a downloadable Excel spreadsheet that contains all the information included below available here: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/states_of_emergency_appendix.xlsx.

| States | Population score | Infection & mortality score | Vaccine score | Basic policies score | Total score | Percent | Final letter grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 58 | 100 | 45 | 25 | 228 | 51% | F |

| Alaska | 52 | 18 | 43 | 55 | 168 | 38% | F |

| Arizona | 29 | 64 | 45 | 45 | 183 | 41% | F |

| Arkansas | 33 | 23 | 25 | 15 | 97 | 22% | F |

| California | 108 | 25 | 67 | 115 | 315 | 71% | C- |

| Colorado | 75 | 22 | 48 | 85 | 230 | 52% | F |

| Connecticut | 84 | 30 | 32 | 115 | 261 | 59% | F+ |

| Delaware | 46 | 22 | 44 | 70 | 182 | 41% | F |

| Federal | 67 | 53 | 35 | 45 | 199 | 45% | F |

| Florida | 44 | 72 | 0 | 45 | 161 | 36% | F |

| Georgia | 47 | 111 | 17 | -5 | 170 | 38% | F |

| Hawaii | 64 | 0 | 31 | 30 | 125 | 28% | F |

| Idaho | 0 | 34 | 39 | 100 | 173 | 39% | F |

| Illinois | 102 | 32 | 44 | 115 | 294 | 66% | D |

| Indiana | 25 | 93 | 32 | 15 | 165 | 37% | F |

| Iowa | 35 | 27 | 25 | 15 | 102 | 23% | F |

| Kansas | 24 | 29 | 55 | 85 | 193 | 43% | F |

| Kentucky | 87 | 10 | 47 | 70 | 214 | 48% | F |

| Louisiana | 90 | 71 | 29 | 45 | 236 | 53% | F |

| Maine | 65 | 69 | 47 | 30 | 211 | 47% | F |

| Maryland | 69 | 49 | 42 | 115 | 274 | 62% | D- |

| Massachusetts | 96 | 28 | 66 | 100 | 290 | 65% | D |

| Michigan | 44 | 19 | 21 | 30 | 114 | 26% | F |

| Minnesota | 72 | 28 | 61 | 100 | 261 | 59% | F+ |

| Mississippi | 24 | 111 | 52 | 30 | 217 | 49% | F |

| Missouri | 21 | 59 | 16 | 85 | 180 | 41% | F |

| Montana | 47 | 70 | 25 | 115 | 256 | 58% | F+ |

| Nebraska | 44 | 90 | 25 | 60 | 219 | 49% | F |

| Nevada | 28 | 15 | 32 | 55 | 130 | 29% | F |

| New Hampshire | 34 | 46 | 50 | 15 | 146 | 33% | F |

| New Jersey | 110 | 27 | 93 | 100 | 329 | 74% | C |

| New Mexico | 76 | 16 | 77 | 100 | 269 | 61% | D- |

| New York | 86 | 88 | 25 | 60 | 258 | 58% | F+ |

| North Carolina | 82 | 34 | 40 | 0 | 157 | 35% | F |

| North Dakota | 50 | 56 | 94 | 10 | 210 | 47% | F |

| Ohio | 94 | 79 | 10 | 70 | 253 | 57% | F |

| Oklahoma | 62 | 52 | 28 | 30 | 171 | 38% | F |

| Oregon | 48 | 0 | 88 | 45 | 181 | 41% | F |

| Pennsylvania | 103 | 46 | 64 | 75 | 273 | 61% | D- |

| Rhode Island | 76 | 38 | 68 | 75 | 257 | 58% | F+ |

| South Carolina | 33 | 78 | 33 | 15 | 158 | 36% | F |

| South Dakota | 26 | 30 | 40 | 30 | 126 | 28% | F |

| Tennessee | 10 | 64 | 40 | 65 | 179 | 40% | F |

| Texas | 32 | 56 | 1 | 15 | 104 | 23% | F |

| Utah | 49 | 0 | 22 | 30 | 101 | 23% | F |

| Vermont | 63 | 40 | 27 | 100 | 230 | 52% | F |

| Virginia | 86 | 22 | 77 | 85 | 270 | 61% | D- |

| Washington | 72 | 28 | 42 | 85 | 227 | 51% | F |

| West Virginia | 71 | 23 | 22 | 100 | 216 | 49% | F |

| Wisconsin | 57 | 28 | 52 | 70 | 207 | 46% | F |

| Wyoming | 2 | 92 | 57 | 100 | 251 | 56% | F |

Appendix Table 2: Population reduction scoring and sources

We awarded points according to the percent change in prison populations from March 2020 to June 2021, plus additional points when states implemented explicit policies for the release of more people. For each one percent reduction of the prison population, states were awarded 2 points, up to a maximum of 60 points. We also awarded points for four potential avenues of increasing prison releases: suspending incarceration for technical parole and probation violations (20 points); instituting accelerated release programs (15 points); expanding compassionate release or medical parole programs (15 points); and allowing the release of those with lower-level offenses (20 points).

| States | March 2020 population | Most recent population | Population reduction | Suspend incarceration for technical violations | Accelerated release policies | Medical/compassionate release policies | Minor offense release policies | Total points (out of 130) | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 21,114 | 17,051 | 19.2% | Yes | No | No | No | 58 | 45.0% |

| Alaska | 4,776 | 4,487 | 6.1% | Yes | No | No | Yes | 52 | 40.1% |

| Arizona | 42,360 | 36,266 | 14.4% | No | No | No | No | 29 | 22.1% |

| Arkansas | 17,501 | 15,898 | 9.2% | No | Yes | No | No | 33 | 25.6% |

| California | 117,639 | 95,107 | 19.2% | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 108 | 83.3% |

| Colorado | 17,585 | 13,650 | 22.4% | No | Yes | Yes | No | 75 | 57.5% |

| Connecticut | 12,290 | 8,957 | 27.1% | No | Yes | Yes | No | 84 | 64.8% |

| Delaware | 5,042 | 4,267 | 15.4% | No | Yes | No | No | 46 | 35.2% |

| Federal | 172,088 | 144,976 | 15.8% | No | No | Yes | Yes | 67 | 51.2% |

| Florida | 93,764 | 80,271 | 14.4% | No | No | Yes | No | 44 | 33.7% |

| Georgia | 55,019 | 46,296 | 15.9% | No | Yes | No | No | 47 | 35.9% |

| Hawaii | 4,836 | 4,134 | 14.5% | No | No | Yes | Yes | 64 | 49.3% |

| Idaho | 7,816 | 7,878 | -0.8%16 | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0.0% |

| Illinois | 36,931 | 27,313 | 26.0% | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 102 | 78.5% |

| Indiana | 26,936 | 23,510 | 12.7% | No | No | No | No | 25 | 19.6% |

| Iowa | 8,533 | 7,680 | 10.0% | No | Yes | No | No | 35 | 26.9% |

| Kansas | 9,804 | 8,650 | 11.8% | No | No | No | No | 24 | 18.1% |

| Kentucky | 12,162 | 9,899 | 18.6% | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 87 | 67.1% |

| Louisiana | 15,066 | 13,522 | 10.2% | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 91 | 69.6% |

| Maine | 2,138 | 1,603 | 25.0% | No | Yes | No | No | 65 | 50.0% |

| Maryland | 20,314 | 18,426 | 9.3% | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 69 | 52.8% |

| Massachusetts | 7,969 | 6,345 | 20.4% | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 96 | 73.7% |

| Michigan | 38,176 | 32,698 | 14.3% | No | No | Yes | No | 44 | 33.6% |

| Minnesota | 8,904 | 7,251 | 18.6% | No | No | Yes | Yes | 72 | 55.5% |

| Mississippi | 17,667 | 15,532 | 12.1% | No | No | No | No | 24 | 18.6% |

| Missouri | 25,740 | 23,057 | 10.4% | No | No | No | No | 21 | 16.0% |

| Montana | 4,508 | 3,908 | 13.3% | Yes | No | No | No | 47 | 35.9% |

| Nebraska | 5,621 | 5,363 | 4.6% | No | Yes | No | Yes | 44 | 34.0% |

| Nevada | 12,384 | 10,640 | 14.1% | No | No | No | No | 28 | 21.7% |

| New Hampshire | 2,433 | 2,016 | 17.1% | No | No | No | No | 34 | 26.4% |

| New Jersey | 18,439 | 10,722 | 41.9% | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 110 | 84.6% |

| New Mexico | 6,573 | 5,708 | 13.2% | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 76 | 58.7% |

| New York | 42,784 | 31,890 | 25.5% | No | No | Yes | Yes | 86 | 66.1% |

| North Carolina | 34,256 | 28,765 | 16.0% | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 82 | 63.1% |

| North Dakota | 1,519 | 1,368 | 9.9% | No | Yes | Yes | No | 50 | 38.4% |

| Ohio | 48,765 | 43,014 | 11.8% | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 94 | 72.0% |

| Oklahoma | 24,956 | 21,615 | 13.4% | No | Yes | No | Yes | 62 | 47.5% |

| Oregon | 14,459 | 12,098 | 16.3% | No | No | Yes | No | 48 | 36.7% |

| Pennsylvania | 46,559 | 38,868 | 16.5% | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 103 | 79.3% |

| Rhode Island | 2,674 | 2,125 | 20.5% | No | Yes | No | Yes | 76 | 58.5% |

| South Carolina | 18,113 | 15,159 | 16.3% | No | No | No | No | 33 | 25.1% |

| South Dakota | 3,701 | 3,228 | 12.8% | No | No | No | No | 26 | 19.7% |

| Tennessee | 21,616 | 20,537 | 5.0% | No | No | No | No | 10 | 7.7% |

| Texas | 140,124 | 117,838 | 15.9% | No | No | No | No | 32 | 24.5% |

| Utah | 6,900 | 5,728 | 17.0% | No | Yes | No | No | 49 | 37.7% |

| Vermont | 1,656 | 1,261 | 23.9% | No | Yes | No | No | 63 | 48.2% |

| Virginia | 29,161 | 23,966 | 17.8% | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 86 | 65.9% |

| Washington | 17,263 | 14,065 | 18.5% | No | Yes | No | Yes | 72 | 55.4% |

| West Virginia | 5,952 | 4,425 | 25.7% | Yes | No | No | No | 71 | 54.9% |

| Wisconsin | 23,591 | 19,271 | 18.3% | Yes | No | No | No | 57 | 43.6% |

| Wyoming | 2,156 | 2,133 | 1.1% | No | No | No | No | 2 | 1.6% |

Population reduction sources and scoring details:

- March 2020 population

- Population data available from The Marshall Project. (Accessed July 1, 2021)

- Most recent population

- Population data available from The Marshall Project. (Accessed July 1, 2021)

- Population reduction

- 0-60 points possible. Prison population reduction by percent change from March 2020 to the most recent population available from The Marshall Project. (Accessed July 1, 2021)

- Suspend incarceration for technical violations

- 0 or 20 points possible. Policies suspending the incarceration of people for technical violations of probation or parole collected from UCLA Law’s COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project and manual search of DOC websites. (Accessed July 1, 2021)

- Accelerated release policies

- 0 or 15 points possible. Policies expediting releases collected from UCLA Law’s COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project and manual search of DOC websites. (Accessed July 1, 2021)

- Medical/compassionate release policies

- 0 or 15 points possible. Policies increasing releases via compassionate release or medical parole collected from UCLA Law’s COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project and manual search of DOC websites. (Accessed July 1, 2021)

- Minor offense release policies

- 0 or 20 points possible. Policies releases people incarcerated for low-level offenses collected from UCLA Law’s COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project and manual search of DOC websites. (Accessed July 1, 2021)

Appendix Table 3: Infection and mortality rate scoring and sources

| Incarcerated population | General population |

|---|

| States | Most recent population | Positive COVID‑19 cases | COVID‑19 infection rate | Number of COVID‑19 deaths | COVID‑19 mortality rate | Population | Positive COVID‑19 cases | COVID‑19 infection rate | Number of COVID‑19 deaths | COVID‑19 mortality rate | Infection rate points (out of 105) | Mortality rate points (out of 40) | Total points (out of 145) | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 17,051 | 1,662 | 9.7% | 66 | 0.39% | 5,024,279 | 551,596 | 11.0% | 11,359 | 0.23% | 77 | 23 | 100 | 69% | |

| Alaska | 4,487 | 2,440 | 54.4% | 5 | 0.11% | 733,391 | 68,428 | 9.3% | 370 | 0.05% | 0 | 18 | 18 | 12% | |

| Arizona | 36,266 | 12,335 | 34.0% | 66 | 0.18% | 7,151,502 | 895,347 | 12.5% | 17,939 | 0.25% | 32 | 32 | 64 | 44% | |

| Arkansas | 15,898 | 11,426 | 71.9% | 52 | 0.33% | 3,011,524 | 350,085 | 11.6% | 5,909 | 0.20% | 0 | 23 | 23 | 16% | |

| California | 95,107 | 49,406 | 51.9% | 227 | 0.24% | 39,538,223 | 3,712,152 | 9.4% | 63,096 | 0.16% | 0 | 25 | 25 | 17% | |

| Colorado | 13,650 | 8,988 | 65.8% | 29 | 0.21% | 5,773,714 | 558,321 | 9.7% | 6,798 | 0.12% | 0 | 22 | 22 | 15% | |

| Connecticut | 8,957 | 4,557 | 50.9% | 19 | 0.21% | 3,605,944 | 349,387 | 9.7% | 8,279 | 0.23% | 0 | 30 | 30 | 21% | |

| Delaware | 4,267 | 2,002 | 46.9% | 13 | 0.30% | 989,948 | 109,770 | 11.1% | 1,694 | 0.17% | 0 | 22 | 22 | 15% | |

| Federal | 144,976 | 45,028 | 31.1% | 249 | 0.17% | 334,735,155 | 33,514,934 | 10.0% | 602,731 | 0.18% | 22 | 30 | 53 | 36% | |

| Florida | 80,271 | 18,072 | 22.5% | 221 | 0.28% | 21,538,187 | 2,334,803 | 10.8% | 37,963 | 0.18% | 48 | 24 | 72 | 50% | |

| Georgia | 46,296 | 3,416 | 7.4% | 93 | 0.20% | 10,711,908 | 1,135,093 | 10.6% | 21,428 | 0.20% | 82 | 30 | 111 | 77% | |

| Hawaii | 4,134 | 1,418 | 34.3% | 9 | 0.22% | 1,455,271 | 36,435 | 2.5% | 515 | 0.04% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | |

| Idaho | 7,878 | 4,302 | 54.6% | 5 | 0.06% | 1,839,106 | 195,089 | 10.6% | 2,154 | 0.12% | 0 | 34 | 34 | 24% | |

| Illinois | 27,313 | 10,919 | 40.0% | 88 | 0.32% | 12,812,508 | 1,392,196 | 10.9% | 25,687 | 0.20% | 8 | 24 | 32 | 22% | |

| Indiana | 23,510 | 3,816 | 16.2% | 51 | 0.22% | 6,785,528 | 754,317 | 11.1% | 13,855 | 0.20% | 63 | 29 | 93 | 64% | |

| Iowa | 7,680 | 4,881 | 63.6% | 19 | 0.25% | 3,190,369 | 374,009 | 11.7% | 6,140 | 0.19% | 0 | 27 | 27 | 19% | |

| Kansas | 8,650 | 6,137 | 70.9% | 16 | 0.18% | 2,937,880 | 318,310 | 10.8% | 5,156 | 0.18% | 0 | 29 | 29 | 20% | |

| Kentucky | 9,899 | 7,909 | 79.9% | 48 | 0.48% | 4,505,836 | 465,330 | 10.3% | 7,223 | 0.16% | 0 | 10 | 10 | 7% | |

| Louisiana | 13,522 | 3,210 | 23.7% | 36 | 0.27% | 4,657,757 | 482,035 | 10.3% | 10,748 | 0.23% | 43 | 28 | 71 | 49% | |

| Maine | 1,603 | 199 | 12.4% | 1 | 0.06% | 1,362,359 | 69,069 | 5.1% | 860 | 0.06% | 39 | 30 | 69 | 47% | |

| Maryland | 18,426 | 4,477 | 24.3% | 30 | 0.16% | 6,177,224 | 462,439 | 7.5% | 9,746 | 0.16% | 19 | 30 | 49 | 33% | |

| Massachusetts | 6,345 | 3,097 | 48.8% | 20 | 0.32% | 7,029,917 | 710,049 | 10.1% | 17,997 | 0.26% | 0 | 28 | 28 | 19% | |

| Michigan | 32,698 | 26,696 | 81.6% | 141 | 0.43% | 10,077,331 | 1,000,241 | 9.9% | 21,013 | 0.21% | 0 | 19 | 19 | 13% | |

| Minnesota | 7,251 | 4,229 | 58.3% | 12 | 0.17% | 5,706,494 | 605,448 | 10.6% | 7,692 | 0.13% | 0 | 28 | 28 | 19% | |

| Mississippi | 15,532 | 1,466 | 9.4% | 23 | 0.15% | 2,961,279 | 322,186 | 10.9% | 7,419 | 0.25% | 77 | 33 | 111 | 76% | |

| Missouri | 23,057 | 6,295 | 27.3% | 48 | 0.21% | 6,154,913 | 621,245 | 10.1% | 9,331 | 0.15% | 32 | 26 | 59 | 40% | |

| Montana | 3,908 | 987 | 25.3% | 6 | 0.15% | 1,084,225 | 113,821 | 10.5% | 1,666 | 0.15% | 40 | 30 | 70 | 48% | |

| Nebraska | 5,363 | 983 | 18.3% | 6 | 0.11% | 1,961,504 | 224,682 | 11.5% | 2,260 | 0.12% | 60 | 30 | 90 | 62% | |

| Nevada | 10,640 | 4,578 | 43.0% | 49 | 0.46% | 3,104,614 | 334,255 | 10.8% | 5,692 | 0.18% | 0 | 15 | 15 | 10% | |

| New Hampshire | 2,016 | 460 | 22.8% | 3 | 0.15% | 1,377,529 | 99,527 | 7.2% | 1,372 | 0.10% | 21 | 25 | 46 | 32% | |

| New Jersey | 10,722 | 4,553 | 42.5% | 52 | 0.48% | 9,288,994 | 1,023,613 | 11.0% | 26,462 | 0.28% | 4 | 23 | 27 | 18% | |

| New Mexico | 5,708 | 2,990 | 52.4% | 28 | 0.49% | 2,117,522 | 205,629 | 9.7% | 4,343 | 0.21% | 0 | 16 | 16 | 11% | |

| New York | 31,890 | 6,603 | 20.7% | 35 | 0.11% | 20,201,249 | 2,113,711 | 10.5% | 53,368 | 0.26% | 51 | 37 | 88 | 60% | |

| North Carolina | 28,765 | 10,111 | 35.2% | 56 | 0.19% | 10,439,388 | 1,013,985 | 9.7% | 13,434 | 0.13% | 10 | 25 | 34 | 24% | |

| North Dakota | 1,368 | 640 | 46.8% | 1 | 0.07% | 779,094 | 110,729 | 14.2% | 1,528 | 0.20% | 18 | 38 | 56 | 39% | |

| Ohio | 43,014 | 6,937 | 16.1% | 135 | 0.31% | 11,799,448 | 1,111,903 | 9.4% | 20,309 | 0.17% | 57 | 22 | 79 | 54% | |

| Oklahoma | 21,615 | 7,455 | 34.5% | 56 | 0.26% | 3,959,353 | 458,483 | 11.6% | 7,395 | 0.19% | 26 | 26 | 52 | 36% | |

| Oregon | 12,098 | 3,617 | 29.9% | 42 | 0.35% | 4,237,256 | 208,834 | 4.9% | 2,778 | 0.07% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | |

| Pennsylvania | 38,868 | 11,195 | 28.8% | 139 | 0.36% | 13,002,700 | 1,212,257 | 9.3% | 27,687 | 0.21% | 23 | 23 | 46 | 32% | |

| Rhode Island | 2,125 | 1,254 | 59.0% | 2 | 0.09% | 1,097,379 | 152,618 | 13.9% | 2,730 | 0.25% | 0 | 38 | 38 | 26% | |

| South Carolina | 15,159 | 3,381 | 22.3% | 42 | 0.28% | 5,118,425 | 597,644 | 11.7% | 9,840 | 0.19% | 52 | 26 | 78 | 54% | |

| South Dakota | 3,228 | 2,345 | 72.6% | 7 | 0.22% | 886,667 | 124,561 | 14.0% | 2,038 | 0.23% | 0 | 30 | 30 | 21% | |

| Tennessee | 20,537 | 6,659 | 32.4% | 42 | 0.20% | 6,910,840 | 867,157 | 12.5% | 12,568 | 0.18% | 35 | 29 | 64 | 44% | |

| Texas | 117,838 | 34,738 | 29.5% | 260 | 0.22% | 29,145,505 | 2,990,703 | 10.3% | 51,273 | 0.18% | 28 | 27 | 56 | 38% | |

| Utah | 5,728 | 3,037 | 53.0% | 18 | 0.31% | 3,271,616 | 415,679 | 12.7% | 2,375 | 0.07% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | |

| Vermont | 1,261 | 279 | 22.1% | 0 | 0.00% | 643,077 | 22,831 | 3.6% | 250 | 0.04% | 0 | 40 | 40 | 28% | |

| Virginia | 23,966 | 9,112 | 38.0% | 56 | 0.23% | 8,631,393 | 680,744 | 7.9% | 11,423 | 0.13% | 0 | 22 | 22 | 15% | |

| Washington | 14,065 | 6,256 | 44.5% | 13 | 0.09% | 7,705,281 | 452,072 | 5.9% | 5,938 | 0.08% | 0 | 28 | 28 | 19% | |

| West Virginia | 4,425 | 1,605 | 36.3% | 13 | 0.29% | 1,793,716 | 164,097 | 9.1% | 2,897 | 0.16% | 1 | 22 | 23 | 16% | |

| Wisconsin | 19,271 | 10,989 | 57.0% | 32 | 0.17% | 5,893,718 | 677,740 | 11.5% | 8,134 | 0.14% | 0 | 28 | 28 | 19% | |

| Wyoming | 2,133 | 342 | 16.0% | 3 | 0.14% | 576,851 | 62,353 | 10.8% | 747 | 0.13% | 63 | 29 | 92 | 63% |

Infection and mortality rate sources and scoring details:

- Most recent population

- Most recent prison population reported by The Marshall Project. (Accessed July 1, 2021).

- Positive COVID‑19 cases

- Number of positive COVID-19 cases in prisons as reported by The Covid Prison Project. (Accessed July 1, 2021).

- COVID‑19 infection rate

- Infection rate calculated by dividing the number of positive cases in prisons by the total prison population.

- Number of COVID‑19 deaths

- Number of COVID-19 deaths in prisons as reported by The Covid Prison Project. For Alaska, Illinois, Maine, Missisippi, and Vermont, deaths in prisons as reported by The Marshall Project. (Accessed July 1, 2021).

- COVID‑19 mortality rate

- Mortality rate calculated by dividing the COVID-19 deaths in prisons by the total prison population.

- Population

- State and national population as reported in the apportionment tables of the 2020 Census.

- Positive COVID‑19 cases

- Number of positive COVID-19 cases in each state and nationally as reported by the CDC. (Accessed July 1, 2021).

- COVID‑19 infection rate

- Infection rate calculated by dividing the number of positive cases in each state or nationally by the total state or national population.

- Number of COVID‑19 deaths

- Number of COVID-19 deaths in states and nationall as reported by the CDC. (Accessed July 1, 2021).

- COVID‑19 mortality rate

- Mortality rate calculated by dividing the COVID-19 deaths in each state and nationally by the state or national population.

Appendix Table 4: Vaccine scoring and sources

Vaccine scores were based on both the prioritization of incarcerated people in vaccine distribution plans and the actual vaccination rate of prison populations. If incarcerated people were of the highest priority in the state’s vaccination distribution plans, the state earned 25 points. If only medically vulnerable people in prisons were in the highest priority or if all incarcerated people were of a medium priority, 10 points were awarded. All others received 0 points. For vaccinations among incarcerated people, states received 1.5 points per percent vaccinated from 50% to 70%, representing 30 total available points. An additional 2 points per percent vaccinated from 70% to 90% was awarded on top of that. All but seven states had vaccinated more than 50% of their incarcerated populations and almost 30 states had vaccinated more than 70% of their prison populations as of July 1, 2021, earning extra points.

| States | Vaccine prioritization | Initial vaccine doses administered to incarcerated people | Most recent population | Incarcerated vaccination rate | Total points (out of 55) | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | High | 10,811 | 17,051 | 63.4% | 45 | 82.0% |

| Alaska | High | 2,781 | 4,487 | 62.0% | 43 | 78.1% |

| Arizona | Medium | 26,291 | 36,266 | 72.5% | 45 | 81.8% |

| Arkansas | High | 7,438 | 15,898 | 46.8% | 25 | 45.5% |

| California | High | 72,185 | 95,107 | 75.9% | 67 | 121.4% |

| Colorado | Not included | 10,801 | 13,650 | 79.1% | 48 | 87.7% |

| Connecticut | High | 4,878 | 8,957 | 54.5% | 32 | 57.6% |

| Delaware | High | 2,668 | 4,267 | 62.5% | 44 | 79.6% |

| Federal | High | 82,099 | 144,976 | 56.6% | 35 | 63.5% |

| Florida | Not included | 35,575 | 80,271 | 44.3% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Georgia | Not included | 28,423 | 46,296 | 61.4% | 17 | 31.1% |

| Hawaii | High | 2,233 | 4,134 | 54.0% | 31 | 56.4% |

| Idaho | Not included | 5,868 | 7,878 | 74.5% | 39 | 70.9% |

| Illinois | High | 17,207 | 27,313 | 63.0% | 44 | 80.9% |

| Indiana | High | 12,842 | 23,510 | 54.6% | 25 | 45.5% |

| Iowa | High | 3,765 | 7,680 | 49.0% | 25 | 45.5% |

| Kansas | Medium | 6,722 | 8,650 | 77.7% | 55 | 100.8% |

| Kentucky | Not included | 7,789 | 9,899 | 78.7% | 47 | 86.1% |

| Louisiana | Not included | 9,375 | 13,522 | 69.3% | 29 | 52.7% |

| Maine | Not included | 1,262 | 1,603 | 78.7% | 47 | 86.3% |

| Maryland | High | 11,263 | 18,426 | 61.1% | 42 | 75.8% |

| Massachusetts | High | 4,800 | 6,345 | 75.7% | 66 | 120.5% |

| Michigan | Not included | 21,027 | 32,698 | 64.3% | 21 | 39.0% |

| Minnesota | High | 5,296 | 7,251 | 73.0% | 61 | 111.0% |

| Mississippi | Not included | 12,572 | 15,532 | 80.9% | 52 | 94.3% |

| Missouri | Low | 13,984 | 23,057 | 60.6% | 16 | 29.0% |

| Montana | High | 1,238 | 3,908 | 31.7% | 25 | 45.5% |

| Nebraska | High | 2,000 | 5,363 | 37.3% | 25 | 45.5% |

| Nevada | Medium | 6,852 | 10,640 | 64.4% | 32 | 57.5% |

| New Hampshire | Not included | 1,614 | 2,016 | 80.1% | 50 | 91.1% |

| New Jersey | High | 9,518 | 10,722 | 88.8% | 93 | 168.3% |

| New Mexico | High | 4,619 | 5,708 | 80.9% | 77 | 139.7% |

| New York | High | 13,035 | 31,890 | 40.9% | 25 | 45.5% |

| North Carolina | High | 17,277 | 28,765 | 60.1% | 40 | 72.9% |

| North Dakota | High | 1,227 | 1,368 | 89.7% | 94 | 171.6% |

| Ohio | Not included | 24,362 | 43,014 | 56.6% | 10 | 18.1% |

| Oklahoma | Medium | 13,331 | 21,615 | 61.7% | 28 | 50.0% |

| Oregon | High | 10,456 | 12,098 | 86.4% | 88 | 159.7% |

| Pennsylvania | High | 28,902 | 38,868 | 74.4% | 64 | 115.9% |

| Rhode Island | High | 1,626 | 2,125 | 76.5% | 68 | 123.7% |

| South Carolina | High | 8,360 | 15,159 | 55.1% | 33 | 59.5% |

| South Dakota | Medium | 2,254 | 3,228 | 69.8% | 40 | 72.3% |

| Tennessee | Low | 15,358 | 20,537 | 74.8% | 40 | 71.9% |

| Texas | Not included | 60,034 | 117,838 | 50.9% | 1 | 2.6% |

| Utah | Medium | 3,322 | 5,728 | 58.0% | 22 | 40.0% |

| Vermont | Not included | 859 | 1,261 | 68.1% | 27 | 49.4% |

| Virginia | High | 19,358 | 23,966 | 80.8% | 77 | 139.2% |

| Washington | High | 8,640 | 14,065 | 61.4% | 42 | 76.6% |

| West Virginia | Medium | 2,568 | 4,425 | 58.0% | 22 | 40.1% |

| Wisconsin | High | 13,094 | 19,271 | 67.9% | 52 | 94.4% |

| Wyoming | High | 1,512 | 2,133 | 70.9% | 57 | 103.2% |

Vaccine sources and scoring details:

- Vaccine prioritization

- 0, 10, or 25 points possible. Data collected by the Covid Prison Project and the Prison Policy Initiative. (Last updated June 2, 2021; accessed July 1, 2021)

- Initial vaccine doses administered to incarcerated people

- Number of initial vaccine doses as reported by UCLA Law’s COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project, The Covid Prison Project, and The Marshall Project. We defined people receiving “at least one dose” of a vaccine as those who were reported as “partially” vaccinated, or having “initiated” vaccination or “received first dose.” This is because many states record vaccinated people twice - once when a two-dose vaccine schedule is started and once when it’s completed; those receiving the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine may be included in both categories as well (as a “first dose” and as “completed”). However, for Arizona, Bureau of Prisons, Hawaii, and Indiana, we presented the vaccination numbers for both doses as there was no partial vaccination data available. For Arkansas and Illinois, vaccination data was collected from media reports. For Florida, Hawaii, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Wyoming, vaccination data was provided by the Department of Corrections’ public information office. (Accessed July 2, 2021)

- Most recent population

- Most recent prison population reported by The Marshall Project. (Accessed July 1, 2021)

- Incarcerated vaccination rate

- Vaccination rate calculated by dividing the number of reported first doses in each prison system by the prison population.

Appendix Table 5: Basic policy changes to address health and mental health needs scoring and sources

In this category, we scored states based on if states had done the bare minimum to protect incarcerated people. This included providing masks, hygiene products, free phone and video calls. In addition, points were rewarded for policies mandating regular staff testing and masks for staff. Given the wide availability of COVID-19 testing at this point in the pandemic, every state should have easily received the maximum number of points.

| States | Incarcerated provided masks | Provided hygiene products | Free phone calls | Free video calls | Medical co‑pays | Staff mask requirement | Staff testing requirement | Total points (out of 115) | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | No | Yes | Yes | No | Suspended in early 2020, reinstated in late 2020 according to communication with the Department of Corrections | Yes | No | 25 | 21.7% |

| Alaska | Yes | Yes | No | No | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | Yes | 55 | 47.8% |

| Arizona | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 45 | 39.1% |

| Arkansas | Yes | No | No | No | Suspended in early 2020, reinstated in December 2020 | Yes | No | 15 | 13.0% |

| California | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No co-pays | Yes | Yes | 115 | 100.0% |

| Colorado | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | Yes | 85 | 73.9% |

| Connecticut | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Suspended co-pays in March 2020, still suspended in July 2021 | Yes | Yes | 115 | 100.0% |

| Delaware | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | Yes | 70 | 60.9% |

| Federal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 45 | 39.1% |

| Florida | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 45 | 39.1% |

| Georgia | Yes | Yes | No | No | Still charging medical co-pays | No | No | -5 | -4.3% |

| Hawaii | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 30 | 26.1% |

| Idaho | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Suspended in early 2020, reinstated in December 2020 | Yes | Yes | 100 | 87.0% |

| Illinois | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No co-pays | Yes | Yes | 115 | 100.0% |

| Indiana | Yes | Yes | No | No | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 15 | 13.0% |

| Iowa | Yes | No | Yes | No | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 15 | 13.0% |

| Kansas | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | Yes | 85 | 73.9% |

| Kentucky | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | Yes | 70 | 60.9% |

| Louisiana | Yes | No | Yes | No | Suspended co-pays in March 2020, still suspended in July 2021 | Yes | No | 45 | 39.1% |

| Maine | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 30 | 26.1% |

| Maryland | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Suspended co-pays in March 2020, still suspended in July 2021 | Yes | Yes | 115 | 100.0% |

| Massachusetts | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Suspended co-pays in March 2020, still suspended in July 2021 | Yes | Yes | 100 | 87.0% |

| Michigan | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 30 | 26.1% |

| Minnesota | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Suspended in early 2020, reinstated in December 2020 | Yes | Yes | 100 | 87.0% |

| Mississippi | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 30 | 26.1% |

| Missouri | Yes | No | Yes | No | No co-pays | Yes | Yes | 85 | 73.9% |

| Montana | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No co-pays | Yes | Yes | 115 | 100.0% |

| Nebraska | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No co-pays | Yes | No | 60 | 52.2% |

| Nevada | Yes | No | Yes | No | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | Yes | 55 | 47.8% |

| New Hampshire | Yes | No | Yes | No | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 15 | 13.0% |

| New Jersey | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Suspended some co-pays in March 2020, suspended all co-pays by December 2020, still have co-pays suspended as of June 2021 | Yes | Yes | 100 | 87.0% |

| New Mexico | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No co-pays | Yes | Yes | 100 | 87.0% |

| New York | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No co-pays | Yes | No | 60 | 52.2% |

| North Carolina | Yes | No | No | No | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 0 | 0.0% |

| North Dakota | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | No | No | 10 | 8.7% |

| Ohio | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | Yes | 70 | 60.9% |

| Oklahoma | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 30 | 26.1% |

| Oregon | Yes | No | Yes | No | No co-pays | Yes | No | 45 | 39.1% |

| Pennsylvania | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No co-pays | Yes | No | 75 | 65.2% |

| Rhode Island | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Suspended co-pays in March 2020, still suspended in July 2021 | Yes | No | 75 | 65.2% |

| South Carolina | Yes | No | Yes | No | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 15 | 13.0% |

| South Dakota | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 30 | 26.1% |

| Tennessee | Yes | No | Yes | No | Suspended co-pays in March 2020, still suspended in July 2021 | No | Yes | 65 | 56.5% |

| Texas | Yes | No | No | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 15 | 13.0% |

| Utah | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | No | 30 | 26.1% |

| Vermont | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No co-pays | Yes | Yes | 100 | 87.0% |

| Virginia | Yes | No | Yes | No | No co-pays | Yes | Yes | 85 | 73.9% |

| Washington | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | Yes | 85 | 73.9% |

| West Virginia | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Suspended co-pays in March 2020, still suspended in July 2021 | Yes | Yes | 100 | 87.0% |

| Wisconsin | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Still charging medical co-pays | Yes | Yes | 70 | 60.9% |

| Wyoming | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No co-pays | Yes | Yes | 100 | 87.0% |

Basic policy changes sources and scoring details:

- Incarcerated provided masks

- -20 or 0 points possible. Data collected by the Covid Prison Project. Alternative sources linked within table. (Accessed July 1, 2021).

- Provided hygiene products

- 0 or 15 points possible. Data collected by the Covid Prison Project. Alternative sources linked within table. (Accessed July 1, 2021).

- Free phone calls

- 0 or 15 points possible. Data collected by the Covid Prison Project. Alternative sources linked within table. (Accessed July 1, 2021).

- Free video calls

- 0 or 15 points possible. Data collected by the Covid Prison Project. Alternative sources linked within table. (Accessed July 1, 2021).

- Medical co‑pays

- 0, 15, or 13 points possible. Data collected by the Prison Policy Initiative from departments of corrections.

- Staff mask requirement

- -20 or 0 points possible. Data collected by the Covid Prison Project. Alternative sources linked within table. (Accessed July 1, 2021).

- Staff testing requirement

- 40 or 0 points possible. Data collected by the Covid Prison Project. Alternative sources linked within table. (Accessed July 1, 2021).

See our appendix tables with scoring and sourcing information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Prison Policy Initiative’s COVID-19 research lead, Emily Widra, for supervising this project; and Research Director Wendy Sawyer for her editorial guidance. The Prison Policy Initiative also wishes to thank the Ford Foundation and Art for Justice Fund, a sponsored project of Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, for their generous support of our ongoing research on COVID-19 in prisons.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. It sounded the national alarm about the threat of coronavirus to jails and prisons with its March 2020 report No need to wait for pandemics: The public health case for criminal justice reform. The organization’s data-driven coverage of the pandemic behind bars continues to advance the national movement to protect incarcerated people from COVID-19.

About the authors

Tiana Herring is a Research Associate at the Prison Policy Initiative. Joining the Prison Policy Initiative during the COVID-19 pandemic, she helped the organization quickly increase its output of analyses about the coronavirus behind bars. Tiana’s work also includes analyses of several important drivers of mass incarceration, including outdated “felony theft” thresholds, the war on drugs, needless parole denials, and money bail.

Maanas Sharma is the Data Science and Policy Analysis Intern at the Prison Policy Initiative. He is a senior at the School of Science and Engineering in Dallas, and is passionate about transdisciplinary equitable policy and incorporating social-scientific understandings into quantitative policy solutions. Maanas is also the founder and Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Interdisciplinary Public Policy and has written extensively on criminal justice reform, protest, and STEM-informed policy.

Footnotes

Our use of the term “reduction” is a purposeful distinction from “release,” as we have found that there are multiple mechanisms impacting prison populations, of which releases are but one part. ↩

For the federal system, scoring was based on a comparison of Bureau of Prison infection and mortality rates to national infection and mortality rates. ↩

For example, Missouri’s proposed vaccine rollout rationalized vaccinating correctional staff before incarcerated people by identifying staff as the likely entry point of the virus into facilities and claiming that the spread can be controlled inside facilities. “Inmates’ confined nature has been amenable to procedural controls to reduce the likelihood of correctional facility outbreaks,” the report states. “As a result, staff now represent the most likely source of a facility outbreak. Vaccination of corrections staff can vastly reduce this source of potential attacks.” Similarly, Arkansas’ Department of Corrections Secretary reported in January 2021 that correctional staff were the main source of infection in state prisons and therefore they were prioritized over the vulnerable incarcerated populations. ↩

Considering the inability to social distance and high rate of people with co-morbidities in prisons, the only real way to protect the health of incarcerated people would have been to release them to their homes instead of keeping them locked in COVID-19 epicenters. ↩

For example, Pennsylvania decided that phone calls and video calls should be free; for five months they allowed video calls via Zoom, before implementing a free, permanent video calling program. In California, the phone provider (GTL) offered free calls to incarcerated people starting in April 2020. ↩

As our review of 14 large scale releases found, mass releases like this have been widely underutilized (during the pandemic, and otherwise) despite past large scale releases not leading to an increase in crime. ↩

New Jersey’s infection rate (also known as the case rate) of 42% means that 42% of the incarcerated population — that is, 42 out of every 100 incarcerated people — have been infected with COVID-19. New Jersey’s mortality rate of 0.48% means that almost 5 out of every 1,000 incarcerated people died of COVID-19. Readers should note that the mortality rate, or the percent of the population that died from COVID-19, differs from the case fatality rate (which we did not include in this report) in that it is a measure of how many people in the entire population die, not just how many people die among those who are infected with COVID-19. ↩

In April 2021, the New York Times reported that several states — including Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi — had not yet tested everyone in prisons. While Alabama’s prisons have among the lowest testing rates and a low infection rate relative to other state prison systems, the fact that they have one of the highest COVID-19 death rates in the nation suggests the virus is going undetected until it is too late. ↩

Oregon’s excellent performance in this regard may be in large part due to the fact that the state was forced by a February 2021 court decision to prioritize incarcerated people for inoculation. ↩

Because of the importance of publicly available data, we only scored states in each category based on the policies and data we could find easily and transparently. If a state had a policy that was not easily accessible on the department of corrections website and was not clear about the implementation, we were not able to award points for the policy. ↩

Arkansas “respectfully declined” to provide information on vaccinations. Because Rhode Island charges $60 for vaccination data, we awarded points based on their vaccine data as of April 16, 2021, retrieved from The Marshall Project. ↩

For a more detailed analysis of prison populations over time during COVID-19, see our most recent prison and jail population briefing from June 2021. (We have been producing a new briefing about every other month as the passage of time and the data warrant.) ↩

Throughout the pandemic we have been analyzing prison populations among 30 states and found that none of these states had decreased their population by more than 30% prior to June 2021. For the purposes of this report, we set the maximum at a 30% decrease (or 60 points). However, one state that was not included in our earlier analyses — New Jersey — did exceed this maximum with a population reduction of 42%. ↩

Some release policies specifically excluded people convicted of “violent or sexual offenses,” while others were not clear about which offense categories would be excluded. For example, Kentucky’s Governor commuted the sentences of 646 people but excluded all people incarcerated for “violent or sexual offenses.” None of the 50 states or the federal Bureau of Prisons implemented policies to broadly allow the release of people convicted of offenses that are considered “violent” or “serious.” People convicted of “violent” offenses should not be excluded from release policies, especially during a pandemic. Moreover, the distinction between “violent” and other offense types is a dubious one; what constitutes a “violent crime” varies from state to state, and acts that are considered “violent crimes” do not always involve physical harm. The Justice Policy Institute explains many of these inconsistencies, and why they matter, in its comprehensive and relevant report, Defining Violence. ↩

We selected 70% as the mid-range cut-off based on President Biden’s goal to vaccinate 70% of U.S. adults before July 4th, 2021. ↩

Idaho’s prison population increased from 7,816 in March 2020 to 7,878 in May 2021 according to data from The Marshall Project. ↩

We compared the federal Bureau of Prisons’ infection and mortality rates to the infection and mortality rates of the United States as a nation. ↩