In 2016, we saw some incredible data visualizations in criminal justice reporting. Here are our five favorites.

by Wendy Sawyer,

December 23, 2016

Every year, researchers find new ways to make criminal justice information more accessible and compelling. In 2016, we saw some incredible data visualizations in criminal justice reporting. Here are our five favorite data visualizations from this year, in no particular order:

- Criminal Charges

Article by Colin Lecher. Interactive by Frank Bi, designer and developer. Michael Zelenko, editor.

Verge

When people are incarcerated, phone calls home are a vital connection to friends, family, and the community. However, those calls come at an exorbitant price. This article uses an innovative time-based data visualization to put that price into a very personal perspective. A timer calculates how much a call from a state prison in your state would cost you if the call was as long as the time it took you to read the accompanying article about the predatory prison telephone industry.

- Bail, Fines, and Fees

Vera Institute of Justice

When you are arrested and booked into jail, you face an expensive choice before you even go to trial. Few people understand the hidden fines and fees that individuals face pre-trial: How much do fees cost? Where do they go? Who pays them?

This 90 second video explains the hidden costs of court-ordered fines, fees, and financial bail in New Orleans, framing bail reform as a common sense choice that benefits everyone.

- Crime in Context

By Gabriel Dance and Tom Meagher. Additional reporting by Emily Hopkins and Mark Hansen. Additional production and design by Andy Rossback.

The Marshall Project

Is crime in America rising or falling? This year saw upticks in violent crime in some U.S. cities, but the uproar about the “rise in crime” had more to do with how news sources present crime data than dramatic changes in criminal offending. At a time when people can’t agree on facts, this interactive chart of violent crime over time in 68 major cities illustrates how our perceptions of crime change depending on how we look at the numbers.

- Police have shot and killed at least 2,195 people since Ferguson

Article by German Lopez and Soo Oh. Interactive map by Soo Oh.

Vox

After the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, some people were quick to call his death an isolated incident. To counteract this narrative and shed light on use of force by the police, the nonprofit Fatal Encounters tracked all available reports — over 2,000 reported deaths — of fatal shootings by law enforcement since Brown’s death. Vox created an interactive map of this data with information about each victim and incident to make it clear that fatal police shootings are not isolated incidents.

- Sandra Bland Died One Year Ago & Since Sandra

Story by Dana Liebelson & Ryan J. Reilly. Data and reporting by Shane Shifflett, with support from a large team of researchers and reporters. Database graphics by Hilary Fung and Alissa Scheller.

Huffington Post

Deaths inside American jails frequently go unnoticed. So after Sandra Bland’s death, the Huffington Post aimed to expose exactly how many people die in jail. After a year-long crowd-sourced investigation of jail deaths, its team of researchers created a powerful infographic detailing the most troubling findings. The article links to the full database of all 815 cases of jail deaths (that’s an average of more than two per day) from July 2015-July 2016.

2016 was a year of big victories for the Prison Policy Initiative. Read about some of the biggest wins in our campaigns this year.

by Kim Cerullo,

December 23, 2016

2016 was a year of big victories for the Prison Policy Initiative. Our campaigns took some big steps forward and, in some cases, those victories culminated in major policy changes.

Here are some of the biggest wins in our campaigns this year:

Prison Gerrymandering

- A federal Judge declared prison gerrymandering in rural Jefferson County, Florida to be an unconstitutional violation of the principle of “one person one vote.” Our staff were expert witnesses in the case.

- In April, Tennessee passed legislation to allow rural counties to avoid prison gerrymandering.

- We organized 100,000 people to submit comments to the Census Bureau demanding an end to prison gerrymandering. This movement was also supported by a letter from 13 U.S. Senators. We are awaiting a decision from the Census Bureau about where incarcerated people will be counted in the 2020 Census.

Driver’s License Suspensions

Protecting Letters from Home

- We followed up on our previous report on postcard-only mail policies in jails this year with Protecting Written Family Communication in Jails, A 50-State Survey.

- Supported by our reports, the movement to end letter bans grew this year. Sheriffs in Macomb County, Michigan and Flagler County, Florida agreed to lift postcard-only policies, and lawsuits are underway to challenge postcard-only policies in Knox County, Tennessee and Wilson County, Kansas.

Other research

We also published a record number of ground-breaking reports to push the national conversation about mass incarceration and over-criminalization. Our most notable reports include:

- Correctional Control: Incarceration and supervision by state

Prison is just one piece of the correctional pie, and we often overlook the leading type of correctional control: probation. This report is the first of its kind and aggregates data on all of the types of correctional control: federal prisons, state prisons, local jails, juvenile incarceration, civil commitment, Indian Country jails, parole, and probation.

- States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2016

Our report and infographic directly situate individual U.S. states in the global context. This updated version reveals that the use of incarceration in every state – even those with relatively progressive policies – is out of step with the international community.

- Detaining the Poor: How money bail perpetuates an endless cycle of poverty and jail time

Detaining people because they are poor is an offensive idea, but until this year it was difficult to prove that this is exactly what the American system of cash bail does. This report uses an obscure and underutilized government dataset to show that the typical bail amount in the U.S. is equivalent to eight months of income for the typical defendant. Our report not only proved the obvious, but we helped reframe the debate to show why modest changes in bail amounts won’t be enough to reverse the tremendous rise in the population of people detained before trial.

- Punishing Poverty: The high cost of probation fees in Massachusetts

In Massachusetts, probation is a much bigger part of the correctional control pie than incarceration. Our new report reveals that being on probation comes at a price: probation service fees in the state cost probationers more than $20 million every year, a cost that largely falls on those who are too poor to pay.

New Jersey bill aims to protect in-person jail visits from video visitation

by Bernadette Rabuy,

December 22, 2016

As our research has shown, local jails are increasingly replacing in-person visitation with glitchy, expensive video visits. Fortunately, New Jersey Assemblyman Gordon Johnson has introduced legislation that would protect in-person visitation from being eliminated in New Jersey jails. Check out the press release from the New Jersey Phone Justice Campaign below:

Legislation Introduced to Restore Face to Face Family Visits in New Jersey Jails

Advocates Applaud Legislators Call for Reduced Cost for those Incarcerated and their Families

For Immediate Release, December 8, 2016

Contact: Karina Wilkinson, KarinaWilkinson@gmail.com

Trenton, NJ – Assemblyman Gordon Johnson (D-Bergen) introduced legislation this week to guarantee face to face family visits for individuals incarcerated in New Jersey. The bill, A4389, would cap costs at 11 cents per minute, ban commissions, require refunds for poor quality and ban fees on professional visits from lawyers and clergy. Similar legislation governing phone rates in prisons and jails was signed into law in August, 2016.

“We applaud Assemblyman Johnson for taking the lead on ensuring that people incarcerated in New Jersey and their families are not taken advantage of by an unregulated industry that is only interested in profits and counties that are looking to gain revenue off of those who can least afford it,” said Karina Wilkinson of the New Jersey Phone Justice Campaign (NJPhoneJustice.org). “We also welcome Congresswoman Duckworth’s efforts at the federal level to require the FCC to regulate video visitation.”

Also this week, Congresswoman Duckworth (IL-8) introduced federal legislation, the Video Visitation in Prisons Act of 2016, that would require the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to regulate video visitation services, including capping rates, ensuring quality and banning the elimination of in-person visits.

Read more here.

For more on video visitation nationally, check out our video visitation page.

New BJS data shows suicide is still the leading cause of death in local jails. And most suicides occur shortly after jail admission.

by Bernadette Rabuy,

December 22, 2016

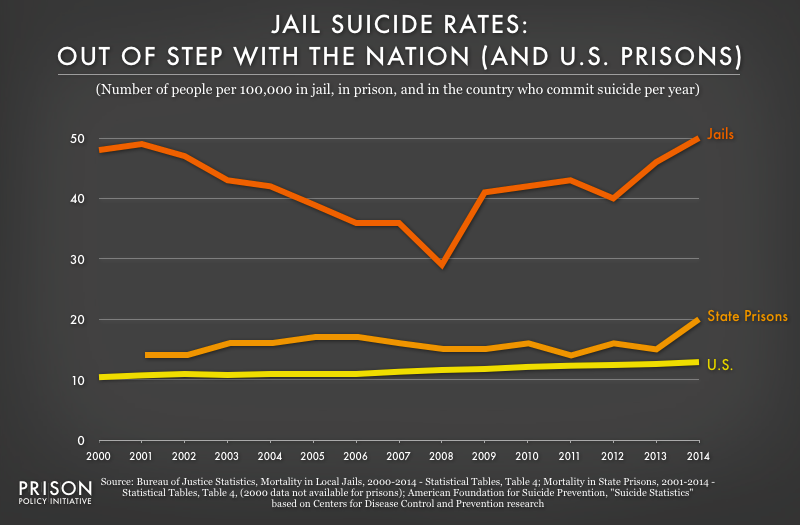

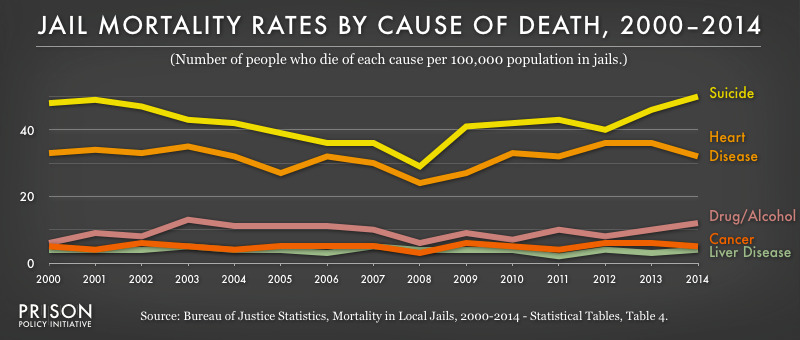

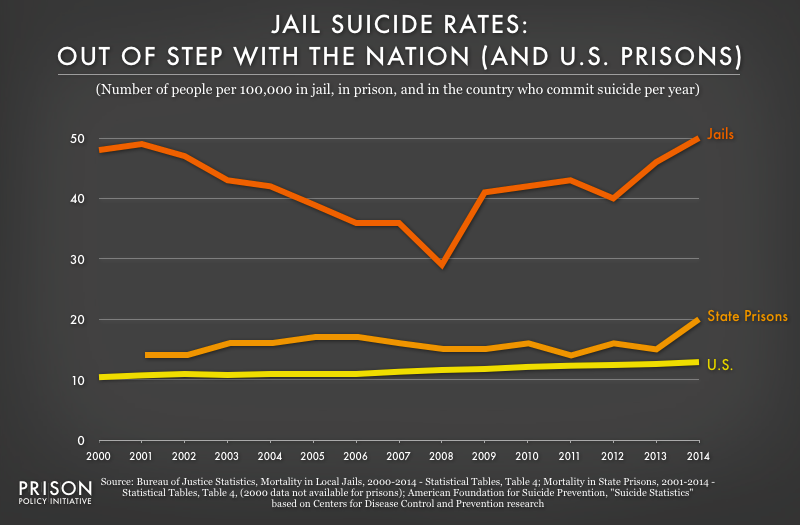

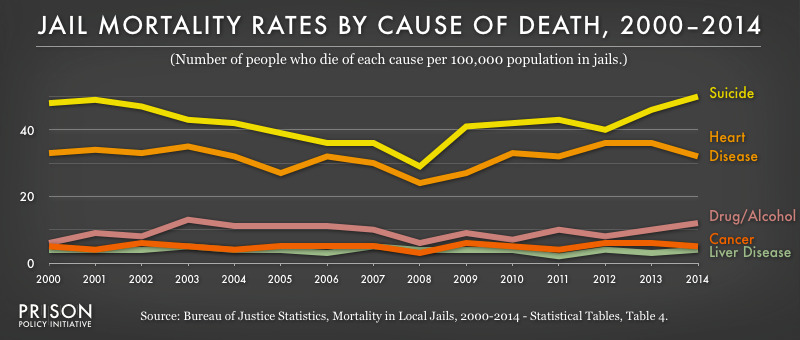

As we wrote last year, suicide in jails is an overlooked national crisis. The rate of suicide in local jails — which generally hold people detained pretrial or convicted of low-level offenses — is far greater than that of state prisons or the American population in general.

According to Bureau of Justice Statistics data released last week, the rates of suicide for 2014 were the highest rates of suicide in either prisons and jails in the fifteen years since the Bureau of Justice Statistics started collecting mortality data. Distressingly, suicide continues to be the leading cause of death in local jails.

In comparison to prisons, local jails experience far higher proportions of unnatural deaths, which include suicides, drug/alcohol intoxication, homicides, and accidents. For example, in 2014, 11% of deaths in state and federal prisons were due to unnatural causes while almost half (49%) of deaths in jails were unnatural. There are a number of reasons for why this could be true such as the disproportionate number of people in jails suffering from mental health challenges or substance abuse or because people are sometimes being booked into jails in their most desperate state.

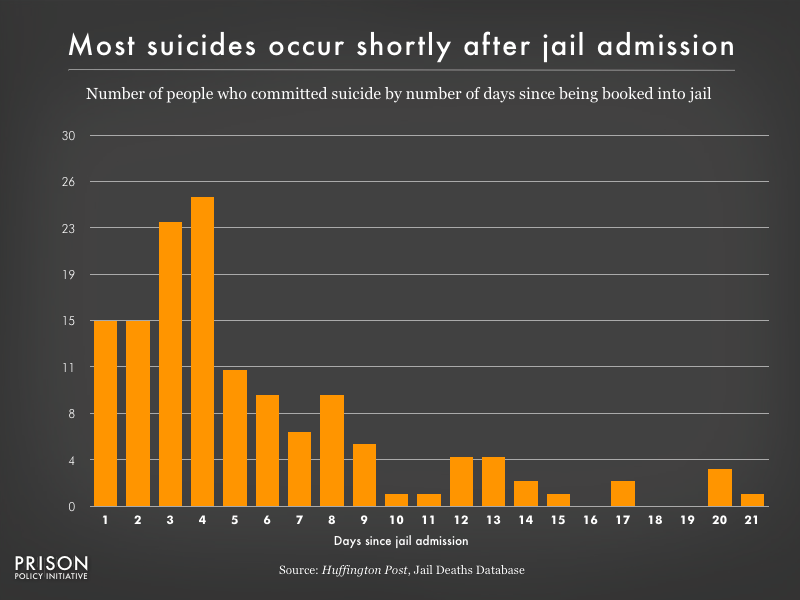

One positive consequence of Sandra Bland’s tragic 2015 death in a Texas jail has been increased attention on jail deaths. For example, the Huffington Post began a groundbreaking project gathering names, cause of death, dates of arrest and death, and other key details for more than 800 people who died in jails and police lockups in the year following Bland’s death. The Huffington Post’s jail deaths database builds on the Bureau of Justice Statistics annual reports to provide more in-depth information on this national crisis. The data shines light on the particular jails in the U.S. with above average numbers of deaths and tells the stories of the people whose deaths might have been initially missing from the mainstream media.

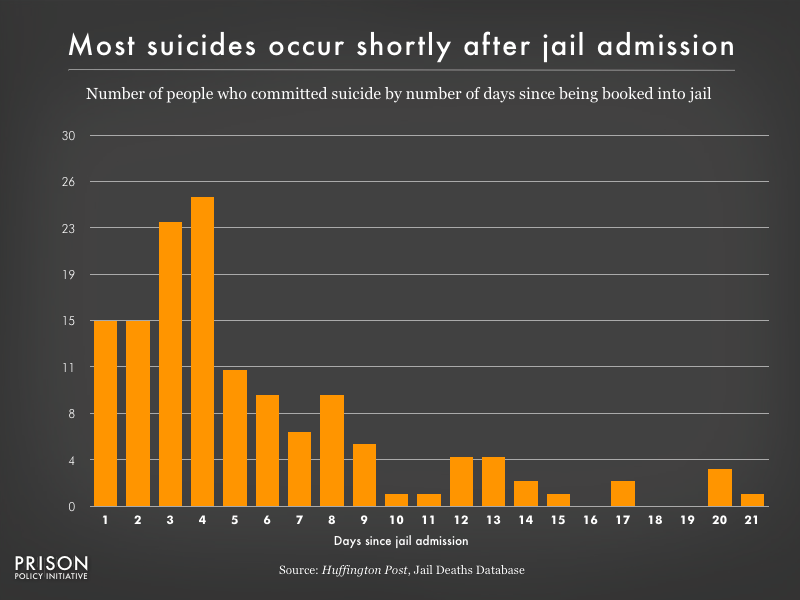

While the Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that 41% of jail deaths occurred within the first week of a person’s jail stay, the Huffington Post’s data goes further, to show that even a few days in jail can be life threatening. The Huffington Post found that 26% of jail suicides occurred within just three days.

Studying the datasets raises urgent questions about the way that jails function such as whether jails are adequately evaluating mental health during intake, how jail staff communicates with family members of the incarcerated during periods of incarceration and when a death occurs, and whether there is appropriate oversight of the thousands of local jails in the U.S.

The data also raises broader, but just as pressing, questions about the dehumanizing experience of incarceration. The high rate of jail suicide should prompt our country to consider whether increasingly popular jail visitation policies that replace in-person visits with video will only increase the isolation of incarceration. The data also supports the idea that mental health services could be more effectively delivered in the community and renews the call for more programs that divert people with mental illness from going to jail in the first place. Further, the high number of suicides that occur within the first few days since jail admission emphasizes why the detention of those awaiting trial, even for a few days, should be treated as a human rights crisis.

Jail suicides are yet another example of how interactions with our criminal justice system can become questions of life or death.

After decades of exponential growth, any news that the population under correctional control is decreasing is good news. But this progress is too slow.

by Wendy Sawyer,

December 21, 2016

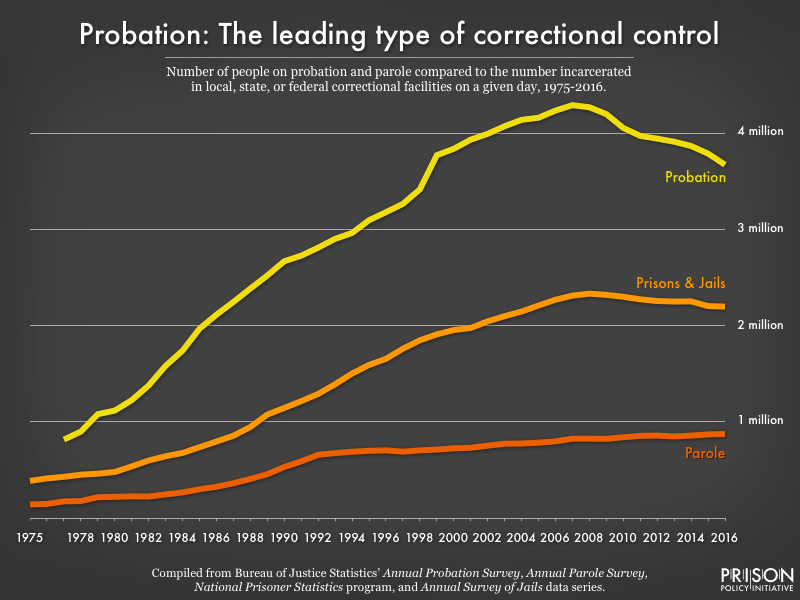

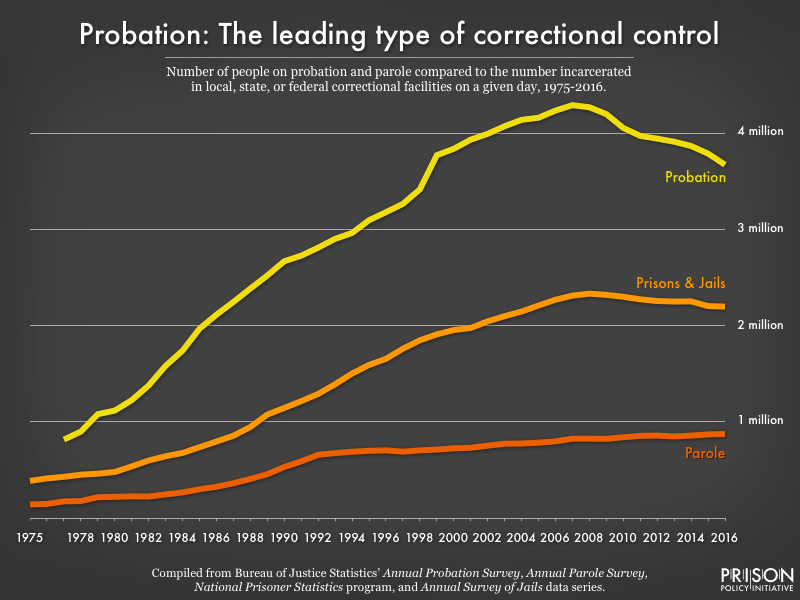

Today, the Bureau of Justice Statistics announced that the number of adults on probation fell again in 2015, marking the eighth year we have seen these numbers decline. This trend represents progress in the movement away from over criminalization.

But don’t get too excited about these probation numbers. 3.8 million people are on probation – still almost twice as many people as are incarcerated. And at the current sluggish rate of decline, it will take 20 years just to undo the increase in probation from the Reagan administration alone. (During that period of record growth, the number of people on probation more than doubled.)

As we have shown, probation is not always the alternative to incarceration it is made out to be. People are often sentenced to probation for minor offenses, but for those who can’t afford fees or make it to every appointment, this seemingly “light” sentence too often leads to incarceration.

After decades of exponential growth, any news that the population under correctional control is decreasing is good news. But this progress is too slow. To make a real dent in the country’s bloated correctional population, policy makers need to advance criminal justice and social policies aimed at reducing the number of people on probation.

Note: The graphic charting the growth of probation, parole, and incarceration over time was updated in December 2018 to include yearend 2016 data (the most recent data available).

Our report on probation fees in Massachusetts is receiving some great press coverage.

by Wendy Sawyer,

December 13, 2016

In case you missed it: Last week, the Prison Policy Initiative released a new report showing that people in Massachusetts’ poorest communities are disproportionately charged probation supervision fees. Our report, which comes on the heels of reports from the state Senate and Trial Court, adds to the mounting evidence that court fines and fees are overdue for a structural overhaul.

Our report is receiving some great press coverage:

Probation fees pose an undue burden

A Boston Globe editorial cites our report to argue that the Legislature should eliminate probation fees.

Probation fees hit poor the hardest, says report

Michael Jonas at CommonWealth magazine puts our report into the context of two recent reports on court fines and fees from the state Senate and Trial Court.

Editorial: State probation fees need reform

The Daily Hampshire Gazette cites our “eye opening” report in an editorial calling for reform.

Report: Probation costs fall disproportionately on the poorest

The Daily Hampshire Gazette’s Emily Cutts provides thorough coverage of our findings and Sen. Mike Barrett’s response.

Poverty, Punishment, and Probation: A Toxic Brew

WGBH’s Daniel Medwed gives some context to the issue of court fines and fees, relating the report to the practices uncovered in Ferguson, Missouri.

Nonprofit encourages elimination of probation fees

Shira Shoenberg provides another overview of the report’s findings and connections to the recommendations of the Trial Court’s report.

Report: Probation fees Hit Poor MA Communities the Hardest

Mike Clifford covers the report for the Public News Service, using one of our graphs.

A relic of the War on Drugs pressures states to automatically suspend the driver’s license of anyone convicted of a drug offense, even if the offense did not involve driving. This practice hits the poor the hardest.

December 12, 2016

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Contact:,

Joshua Aiken

jaiken [at] prisonpolicy.org

(413) 527-0845

Easthampton, MA — A 26-year-old federal law passed at the height of the War on Drugs pressures states to automatically suspend the driver’s license of anyone convicted of a drug offense, even if the drug offense did not involve driving. A new report by the non-profit non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative tracks the growing state rejection of this federal policy, and shines a light on the states that continue to implement this outdated and ineffective law. These stragglers make it harder for people with drug convictions to meet economic needs, familial obligations, and even court requirements, all of which require driving.

The report, Reinstating Common Sense: How driver’s licenses suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving are falling out of favor provides, for the first time, a national overview of license suspension statutes. “While the majority of states have opted-out of the federal law,” said Joshua Aiken, author of the report, “12 states and Washington D.C. have continued to hurt their own citizens with these needless license suspensions.”

Currently, Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, Michigan, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Washington D.C. automatically suspend driver’s licenses for non-driving drug offenses. “These drug suspension laws are one of the most punitive and unnecessary side effects of the War on Drugs,” notes Aiken, the Policy Fellow at the Prison Policy Initiative. “The report finds that the burden of these suspensions fall most heavily on low-income people and people of color.”

The report finds that driver’s license suspensions can prevent people with past drug convictions from meeting their civil and familial responsibilities. “There is no evidence that these license suspensions deter crime, but the evidence is clear that these laws harm our society,” says Aiken.

Driver’s license suspensions have serious consequences for drivers and the states. 86% of Americans rely on a motor vehicle to get to work, so a suspended driver’s license can often limit employment opportunities. The report shows that in many low-income communities impacted by non-driving drug violations, the vast majority of jobs cannot be reasonably accessed using public transportation. In one study, 45% of respondents lost their job after their license was suspended. 88% of people reported decreased income. The report also discusses the unintended fiscal burden that the federal law places on state governments.

The number of states that automatically suspend driver’s licenses for drug convictions is shrinking rapidly. In just the last three years, five states (Indiana, Delaware, Georgia, Massachusetts, and Ohio) have ended the practice.

Based in Easthampton, Massachusetts, the Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The organization is most well-known for sparking the movement to end prison gerrymandering and for its big picture data visualization “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie.” The organization’s 2014 report “Suspending Common Sense in Massachusetts: Driver's license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving” led to reform in that state.

NPR covers video visitation, and reform legislation is introduced in Congress.

by Peter Wagner,

December 8, 2016

It’s been a big week for the movement for telephone justice:

Can you help us raise $80,000 by the end of the year?

by Peter Wagner,

December 8, 2016

There is another new opportunity to support our work for justice reform. I wrote last week about our $30,000 matching challenge, but another donor has come forward to raise the stakes by $50,000!

The first $80,000 we raise by the end of the 2016 will be automatically matched by other donors. We have a long ways to go to meet this goal (see thermometer installed at the top of the page).

Your support will help us to continue to lead campaigns and produce reports that are reshaping the debate around criminal justice in this country. Just today we released Punishing Poverty: The high cost of probation fees in Massachusetts, and we have another exciting top-secret report scheduled for release on Monday.

We have even larger plans for 2017, but we need your support to make these plans a reality. Can you consider making a gift to support our work today?

Thank you.

The state brings in over $20 million in revenue from monthly probation fees each year. The problem? Probation rates are highest in the lowest-income communities.

December 8, 2016

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: December 8, 2016

Contact:

Wendy Sawyer

wsawyer [at] prisonpolicy.org

(413) 527-0845

Easthampton, MA – The state brings in over $20 million in revenue from monthly probation fees each year. The problem? Probation rates are highest in the lowest-income communities, according to a new report by the Prison Policy Initiative. Punishing Poverty: the high cost of probation fees in Massachusetts analyzed probation cases and income data for the state’s 62 District Court locations.

“The state is charging monthly probation fees to the people who can least afford to pay them,” said Wendy Sawyer, the author of the report, “and setting them up for failure.”

In Massachusetts, there are currently about 67,000 people on probation who are charged a monthly fee of $50-65. The report explains that it is harder for people who cannot afford these monthly probation fees to succeed in meeting the conditions of their probation. When someone on probation fails to pay their fee, it counts as a “probation violation,” which can lead to more fees, license suspension, arrest, and can even land them back in jail.

The Prison Policy Initiative’s report adds to the growing body of research on the harms of the state’s court-imposed fines and fees. The report follows on the heels of two recent reports by the Trial Court and by the Senate, which explain the problems with court-imposed fines and fees that can lead to incarceration for people who fail to pay.

Punishing Poverty offers a comprehensive look at probation fees, including their roots in 1980s “tough on crime” politics and the problems they cause for probationers and courts.

The report unearths a long-forgotten legislative research brief from 1988 that explains how this policy came to pass. Probation fees were instituted as a misguided attempt to plug a budget in crisis, passed by legislators capitalizing on the “tough on crime” political climate. The 1988 brief also reveals that legislators understood the inherently coercive nature of probation fees.

The state faces a budget shortfall again in FY 2017, but Sawyer argues that charging probationers fees they cannot afford is no solution. “The state needs to recognize that the people in the criminal justice system are among the state’s poorest,” she says. “Fines and fees just make their situations worse, not to mention making more work for the courts.”

Punishing Poverty provides recommendations for far-reaching reforms for the legislature, judiciary, and probation. An appendix includes detailed information comparing each court location’s probation and income data. The most striking findings from the report’s analysis of probation and income data are large disparities between the probation rates of the state’s wealthiest and poorest communities:

-

The courts serving the populations with per capita incomes below $30,000 have probation rates 88% higher than in those serving the populations with incomes over $50,000.

-

Just ten court locations where the population has below-average incomes account for a full third of District Court probation cases.

-

Residents of Holyoke are sentenced to probation at a rate more than three times higher than in Newton. But Holyoke’s probationers can scarcely afford to pay this regressive tax; the average income in that area is $21,671.

The Easthampton, Massachusetts-based Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization. The organization is most well known for sparking the movement to end prison gerrymandering and for its big picture data visualization “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie.”

The new report, Punishing Poverty: the high cost of probation fees in Massachusetts, is available at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/probation/ma_report.html