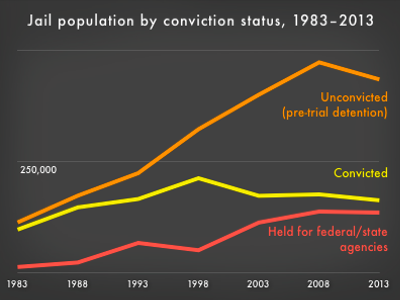

Since the 1980's crime has fallen, but the number of people in jails tripled. Our new report finds two troubling explanations for why this has occurred: the rise in pre-trial detention and the renting of jail space to other authorities.

May 31, 2017

Contact:

Joshua Aiken

jaiken [at] prisonpolicy.org

(413) 527-0845

Easthampton, Mass. — State capitols share responsibility for growing jail populations, charges a new report by the Prison Policy Initiative. “Jails are ostensibly locally controlled, but the people held there are generally accused of violating state law, and all too often, state policymakers ignore jails,” argues the new report, Era of Mass Expansion: Why State Officials Should Fight Jail Growth.

The fact that jails are smaller than state prison systems and under local control has allowed state officials to avoid addressing the problems arising from jail policies and practices. “Reducing the number of people jailed has obvious benefits for individuals, but also helps states curb prison growth down the line,” says Joshua Aiken, report author and Policy Fellow at the Prison Policy Initiative.

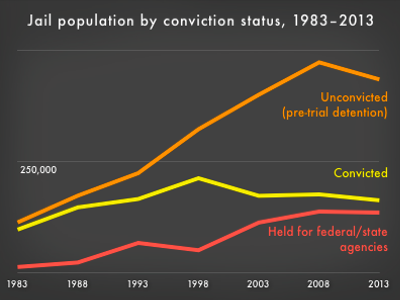

Every year, 11 million people churn through local jail systems, mostly for minor violations of state law. Of the 720,000 people in jails on a given day, most have not been convicted of a crime and have either just been arrested or are too poor to make bail. And since the 1980s, crime has fallen but the number of people jailed has more than tripled.

The new report finds that the key driver of jail growth is not what one might expect – courtroom judges finding more people guilty and sentencing them to jail. In fact, the number of people serving jail sentences has actually fallen over the last 20 years. Instead, the report finds two troubling explanations for jail growth:

- An increasing number of people held pre-trial.

- Growing demand from federal and state agencies to rent cell space from local jails.

Recognizing the importance of state-specific data for policymakers and advocates, the report offers more than a hundred graphs that make possible state comparisons of jail trends. The report uncovers unique state problems that drive mass incarceration:

- In some states, state officials have not utilized their ability to regulate the commercial bail industry, which has profited from the increased reliance on money bail and increased bail amounts. These trends have expanded the pre-trial population dramatically over time.

- In other states, state lawmakers have expanded criminal codes, enabled overzealous prosecutors, and allowed police practices to play a paramount role in driving up jail populations, while underfunding pre-trial programs and alternatives to incarceration.

- In 25 states, 10% or more of the people confined in local jails are being held for state or federal agencies, with some counties even adding capacity to meet the demand. This report is the first to be able to address the local jail population separately from the troubling issue of renting jail space.

Era of Mass Expansion draws particular attention to the states where the dubious practice of renting jail space to other authorities contributes most to jail growth. “Local sheriffs, especially in states like Louisiana and Kentucky, end up running a side business of incarcerating people for the state prison system or immigration authorities,” explains Aiken. “Renting out jail space often creates a financial incentive to expand jail facilities and keep more people behind bars.” The report finds that renting jail space for profit has contributed more to national jail growth since the 1980s than people who are being held by local authorities and who have actually been convicted of crimes.

For state policymakers, the report offers 10 specific recommendations to change how offenses are classified and treated by law enforcement, eliminate policies that criminalize poverty or create financial incentives for unnecessarily punitive practices, and monitor the upstream effects of local discretion. “There are plenty of things local officials can do to lower the jail population,” says Aiken. “With this report, I wanted to bring in state-level actors by showing how much of the solution is in their hands.”

The non-profit non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The organization produces big-picture data publications like Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie to help people fully engage in criminal justice reform. Era of Mass Expansion builds upon the organization’s 2016 analysis of the cycle of poverty and jail incarceration, Detaining the Poor: How money bail perpetuates an endless cycle of poverty and jail time.

The new report is available at www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/jailsovertime.html.

If Tom Gores and Platinum Equity are trying to improve lives, Securus is the wrong investment. As the second-largest prison and jail telecom company in the country, is arguably one of the most exploitative companies profiting from mass incarceration.

by Wendy Sawyer,

May 18, 2017

Detroit Pistons owner Tom Gores has styled himself a hometown hero in Michigan, but his company’s current bid to acquire prison telecom company Securus Technologies suggests he cares far more about profits than he does people.

“It’s really Tom’s idea that [the Pistons] are a great platform, they’re a community asset and, with that, requires us to be socially responsible…. It’s about inspiring our youth, unifying our community, and improving the lives of others.” – Arn Tellem, vice chairman of Palace Sports & Entertainment (owned by Platinum Equity)

If Gores is trying to improve lives, Securus is the wrong investment. As the second-largest prison and jail telecom company in the country, it is arguably one of the most exploitative companies profiting from mass incarceration. It’s certainly among the worst of the bunch for the people forced to use their ever-expanding array of criminal-justice-related “services.” (See sidebar)

Securus exploits the need for incarcerated people and families to maintain contact, charging extremely high rates and fees for phone calls. Some of the money goes back to the prison or jail in the form of commissions, so the incentive for Securus and the facilities is to charge as much as possible. In Michigan, that means a 15-minute in-state call can cost families over $22. In response to objections, rival company GTL has lowered rates in Michigan state prisons to about 20 cents per minute, but Securus continues to charge over $1 per minute.

And who are the people paying Securus those high rates and fees? Family and friends, many of whom are low-income and people of color – and the same community members whom Mr. Gores supports through his charitable endeavors. A Detroit sports fan or concert-goer might question the sincerity of Mr. Gores’ philanthropic efforts when the outrageous fees they pay Securus end up lining his pockets.

So why is Gores’ private equity firm, Platinum Equity LLC, interested in Securus, when its exploitative practices are well-documented and bound to invite criticism? Platinum is either ignorant of the company’s exploitative business model (unlikely) or it sees an opportunity too good to pass up.

Over the past 10 years, Securus has expanded its business to avoid pesky regulations that might restrict exploitative practices, and the current political climate may reward this strategy. Between 2007 and 2015 the company shifted from 100% regulated businesses to 65% deregulated businesses within the expansive world of “user-funded” criminal justice services, like telemedicine, commissary, probation and parole supervision, and GPS monitoring.

Securus’ remaining regulated business, its large phone provider service, may also be shielded from federal oversight under the new FCC chair, Ajit Pai. The FCC’s recent change in leadership ended the government agency’s willingness to defend the caps it placed on prison phone calls in 2015. That change improved the odds that prison phone calls will continue to yield steady profits for people and companies willing to ignore the impact on the people forced to pay obscene rates and fees.

By investing in Securus, Tom Gores’ Platinum Equity joins the ranks of those companies that care about social responsibility – only when it does not affect their bottom line.

As sheriffs consider eliminating in-person visitation in jails, the firsthand experiences of incarcerated people and their families remind us that in-person visitation is crucial to the reentry process and reducing recidivism.

by Emily Widra,

May 9, 2017

A little more than a year ago, I wrote a blog post about the psychological research on the difference between video communication and face-to-face communication. Throughout the literature, I found that video communication – and therefore video visitation – falls short of face-to-face, in-person interactions.

The Prison Policy Initiative has been following the disturbing trend of jails ending in-person visitation and replacing it with video visitation. The problems with eliminating in-person visits come up again and again in the news coverage; but every time, the people behind bars and their families say it best. When looking for reasons to protect in-person visitation, all we need to do is listen to them:

“They’re probably less than 500 feet away from you and you feel like they’re still in another state…You can never look someone in the eye. It’s impossible.”

– Richard Fisk, on video visitation with his mother, after she travelled 1,700 miles to sit at a video screen in the Travis County Correctional Facility, where he was incarcerated

“Those personal, intimate aspects of someone who loves you — that doesn’t show.”

– Jorge Renaud, on his experience with video-visitation in a Texas jail in 2014

“Even if it’s through plexiglass, at least you can have some kind of live interaction with your loved one… That would have made it better for me and him to maintain that human contact. Just because someone committed a crime doesn’t stop the love you have with them.”

– Susan Gregory, on her visits with her husband, who was incarcerated for six months in an Arizona facility where in-person visitation was eliminated

“It’s not something you can quantify… Eye contact is a huge deal. It’s blowing them kisses and putting your hand to the glass. The kids get lost with the video terminals. It’s just not the same experience. It’s a disconnected feeling.”

– Lauren Johnson, on her family’s decision to travel and wait for in-person visitations instead of opting for video visitation at the Travis County Correctional Facility, prior to the elimination of in-person visitation

“As a kid, I went to prison. The environment in there, you are depraved of contact from family… Just seeing someone from the glass and putting your hand up there makes a positive difference for inmates. You cannot do that with video visitation.”

– Josh Gravens, Soros Justice Fellow, previously incarcerated at age 12 for three years, discussing the psychological and emotional benefits of in-person visitation

These stories illuminate the real-life deficits of video visitation that explain why families prefer in-person, through-the-glass visits. As I found last year, research shows that video communication hinders the natural flow of conversation, slows the process of establishing trust, impedes the intimacy and social connection of in-person interactions, shortens conversations, and restrains interactivity and responsiveness. As these quotes show, incarcerated people and their families maintain trust, relationships, and community connection through eye-contact and face-to-face interactions.

As sheriffs in New Jersey and California consider eliminating in-person visitation in jails, the firsthand experiences of incarcerated people and their families remind us that in-person visitation is crucial to the reentry process and reducing recidivism.

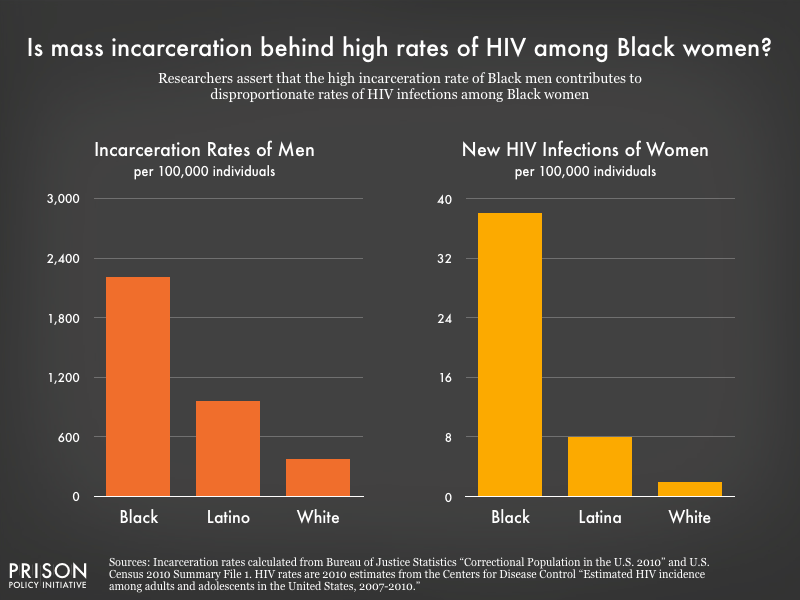

Current research points to an unexpected contributor to the high rates of HIV infection among Black women: the mass incarceration of Black men.

by Wendy Sawyer and Emily Widra,

May 8, 2017

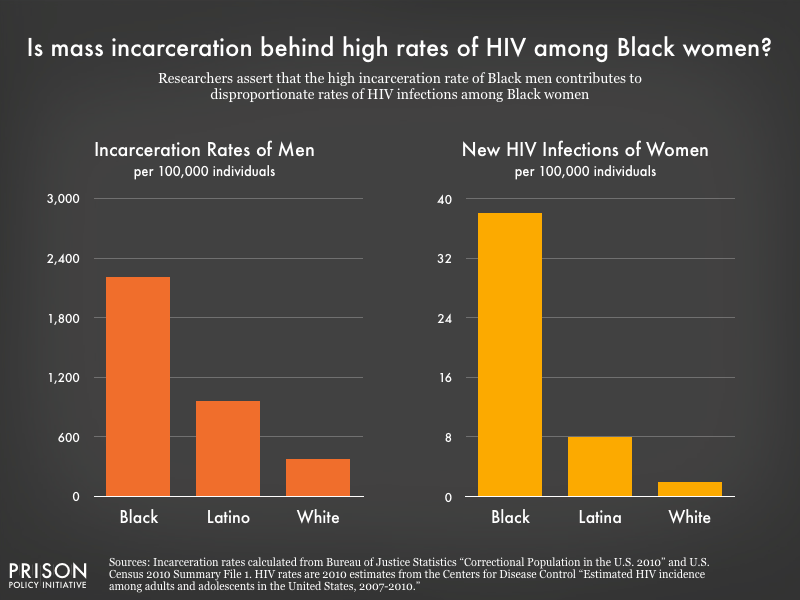

Over 7,000 women in the United States received a new HIV diagnosis in 2015, and over 60% of those women were Black, despite the fact that Black people represent just 12% of the overall U.S. population.

While policymakers seem oblivious to this pressing health problem, Prof. Laurie Shrage’s 2015 New York Times op-ed drew our attention to research that unravels the complicated nature of HIV risk factors among Black women. In general, Black men and women report less risky drug use and less risky sexual behaviors than whites; so what accounts for the disproportionately high number of HIV infections among Black women?

From researchers, an unexpected explanation

The current interdisciplinary research points to an unexpected explanation: the mass incarceration of Black men.

Two University of California professors, Rucker Johnson & Steven Raphael investigated the complicated relationship between infection rates and incarceration. Their findings reveal that “the lion’s share of the racial differentials in AIDS infections rates for both men and women are attributable to racial differences in incarceration trends.”

The “trend” in question, of course, is the hyper-incarceration of Black men over the last few decades. Between 1974 and 2001, the likelihood of incarceration for Black men increased from 13.4% to 32.2%. The racial disparity is now extreme: in 2015, Black men were almost six times more likely to be incarcerated than white men.

Johnson and Raphael (2009) conclude that if it weren’t for the racial disparity in male incarceration, Black women would have lower rates of HIV infection than white women.

Johnson and Raphael (2009) conclude that if it weren’t for the racial disparity in male incarceration, Black women would have lower rates of HIV infection than white women.

To explain the connection between the disproportionate incarceration of Black men and the HIV rates of non-incarcerated Black women, Johnson and Raphael point to:

- high rates of HIV in prisons

- risky sexual activity among men in prisons

- sexual networks with a large number of lifetime partners

- destabilized relationships (defined by periodic absences of the incarcerated partner), and

- a disproportionate ratio of non-incarcerated Black men to women.

To begin with, they found that the rates of risky sexual activity, and therefore the risk of HIV infection, among incarcerated men is significantly higher than in non-incarcerated populations. In particular, the sexual networks in prisons – where “a small number of individuals have repeated sexual encounters with a large number of partners” – increases the efficiency of HIV transmission. And considering that condoms are widely considered contraband in correctional facilities, the risk for STIs is heightened regardless of the number of sexual partners.

Women who have a sexual partner with a history of incarceration are at an elevated risk of HIV infection. By forcing partners to spend long stretches of time apart, incarceration often causes breakups or on-again, off-again relationships, increasing the number of lifetime partners – a major risk factor for HIV – for both the incarcerated and non-incarcerated partners.

With 1 in 15 Black adult men behind bars , incarceration also disproportionately reduces the ratio of Black men to Black women. Because the overwhelming majority of sexual relationships and marriages occur between individuals of the same age group, race, ethnicity, and geographic location, this means Black women have less ability to be selective in choosing a partner and/or in negotiating safer sexual behaviors. In particular, heterosexual Black women are more likely to have sexual partners in “high risk groups,” that is, men with a history of incarceration.

Prevention: Improving re-entry services

Incarceration does not just impact the lives of those behind bars; it reaches far into communities, jeopardizing the health status of the partners and families these men return to. This is largely because of the particular vulnerability of formerly incarcerated people when they are first released. At the same time these men are returning to their relationships and families, their risk of transmitting HIV is elevated and their access to treatment is limited.

Dr. Chris Beyrer, former president of the International AIDS Society, explains that “people are being released [from prison] without access to services and they experience treatment interruption,” which in turn causes their viral load to spike. After release, Black men are not connected to structured care in the community to assure treatment adherence (there are some facilities with HIV transitional case management, but not much data on how effective and replicable these programs are.)

In a recent study of HIV care among criminal justice involved individuals in Washington, D.C., researchers found that despite reliable access to HIV treatment providers prior to, during, and after incarceration, HIV treatment adherence drops significantly after being released.

The stigma of HIV infection may also be part of the problem. As Phill Wilson, President of the Black AIDS Institute, explains, “they’re stigmatized because they’re Black, stigmatized because they’re ex-prisoners and they’re stigmatized because they’re HIV positive… What sane person is actually going to disclose that they’re HIV positive?”

The higher risk of HIV infection among women is one of many collateral consequences of mass incarceration facing communities of color. To better protect Black women from HIV infection, we need to eliminate the gap in HIV/AIDS treatment for Black men released from prisons and jails. Correctional agencies should coordinate with community health providers to ensure continuity of care and support treatment adherence. Reuniting with partners and families should improve the well-being of communities, not add to their problems.

This Mother's Day, 120,000 incarcerated mothers will spend the day apart from their children. The good news is, this year, you can take action to help reconnect children to their mothers.

by Wendy Sawyer,

May 8, 2017

This report is has been updated with a new version for 2022.

This Mother’s Day, 120,000 incarcerated mothers will spend the day apart from their children. Over half of all women in U.S. prisons – and 80% of women in jails – are mothers, most of them primary caretakers of their children. An estimated 9,000 women are pregnant upon arrival to prison or jail each year. Yet most of these women are incarcerated for non-violent offenses, and many are held in jail awaiting trial because they can’t afford bail. The good news is this year, you can take action to help reconnect children with their mothers.

National Mama’s Bail Out action

During this week, a collection of over two dozen local and national organizations will bail out as many mothers as possible, who would otherwise spend Mother’s Day in a cell simply because they cannot afford bail. This effort focuses on bailing out Black mothers (including birth, trans, and other women who mother); Black children are seven times more likely than white children to have a parent incarcerated. Over a dozen cities are participating across the country. You can donate bail funds here (link no longer active).

Bills to keep primary caretakers out of prison

In Massachusetts, the “Primary Caretakers” bill (S. 770) would allow parents and other primary caretakers convicted of nonviolent crimes to request a non-prison alternative. Once enacted, courts would make written findings about caregiver status and availability of alternatives before sentencing. Tennessee’s HB 825 and SB 919 follow the model of the Massachusetts bill. If you live in one of these states, you can find your legislator to weigh in on these bills.

Harms to children caused by parental incarceration

Keeping parents out of jail and prison is critical to protect children from the known harms of parental incarceration, including:

- Traumatic loss marked with feelings of social stigma and shame and trauma-related stress

- More mental health problems and elevated levels of anxiety, fear, loneliness, anger, and depression

- Less stability and greater likelihood of living with grandparents, family friends, or in foster care

- Difficulty meeting basic needs for families with a member in prison or jail

- Lower educational achievement, impaired teacher-student relationships, and more problems with behavior, attention deficits, speech and language, and learning disabilities

- Problems getting enough sleep and maintaining a healthy diet

- More mental and physical health problems later in life

Incarceration punishes more than just individuals; entire families suffer the effects long after a sentence ends. Mother’s Day reminds us again that people behind bars are not nameless “offenders,” but beloved family members and friends whose presence – and absence – matters.

Thank you for making Valley Gives 2017 a success!

by Wendy Sawyer,

May 3, 2017

Yesterday, we raised over $2,500 in individual donations through Valley Gives, an annual giving event in western Massachusetts. We are grateful to all of our supporters: our neighbors in the Pioneer Valley and allies across the country that sustain us year after year, and new friends who have just recently discovered our work. Together with a generous donor who offered a matching gift of $2,500, we raised over $5,000, exceeding our Valley Gives goal.

Over the years, individual donor support has allowed us the flexibility to take on critical emerging issues, like the exploitation of incarcerated people and their families and bail practices that punish the poor. The Prison Policy Initiative has a small staff but accomplishes so much because we are able to draw on a broad network of dedicated reform-minded folks who are generous with their time, thoughts, and resources. We are thrilled to welcome some new supporters to the movement through Valley Gives, and thank you all for helping make it such a success!

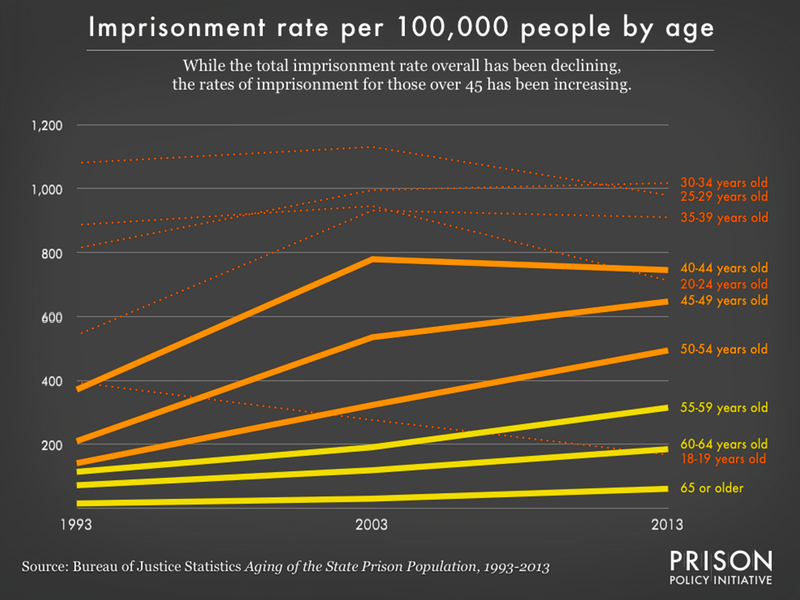

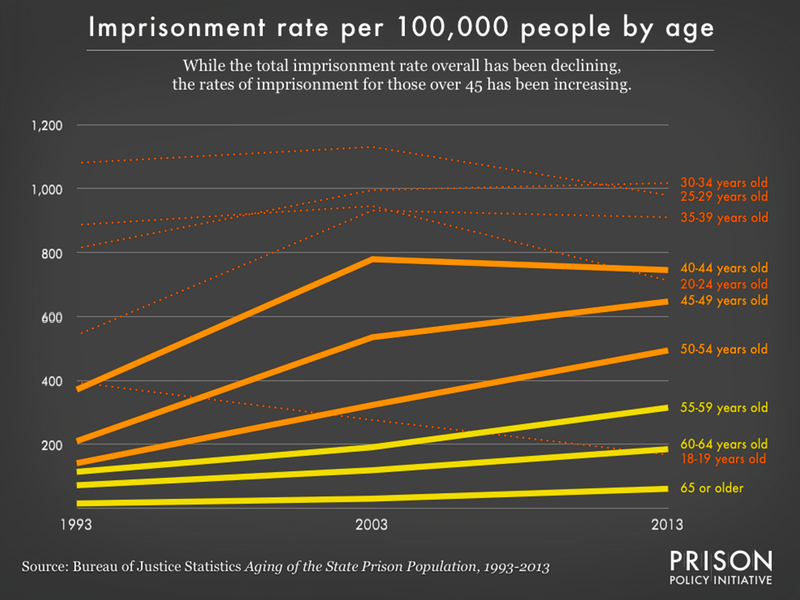

We estimate that more than 44,000 people 45 and older experience solitary in state prisons each year. As prisons continue to get grayer, policymakers must understand that denying older incarcerated people access to sunlight, exercise, and interaction with other people and spaces is both inhumane and fiscally irresponsible.

by Lucius Couloute,

May 2, 2017

Recently released research finds that thousands of older incarcerated people are being forced to live in some form of solitary confinement on any given day. The practice of cutting human beings off from human contact is widely condemned, but this practice is particularly troubling since it means we are subjecting a large number of older adults to living conditions that can cause or exacerbate serious medical conditions. As prisons continue to get grayer, policymakers must understand that denying older incarcerated people access to sunlight, exercise, and interaction with other people and spaces is both inhumane and fiscally irresponsible.

‘Solitary confinement’ is, in fact, a highly contested term; some prison systems deny that they employ solitary confinement and prefer lighter, more administrative-sounding phrases such as SHUs (special housing units) or SMUs (special management units). Terminology aside, these units mean segregation from the rest of the prison population and people are typically forced to remain in their cells for over 22 hours a day with minimal human interaction. Solitary confinement is used at the discretion of correctional staff for a variety of reasons, ranging from punishing (or protecting) individuals, to housing people when other, normal, cells are not available.

Whatever name it’s given, and whatever the reasons for putting people there, the evidence is clear that solitary confinement causes undeniable harm and can create a host of negative psychological issues for all people including:

- Anxiety

- Hallucinations

- Withdrawal

- Aggression

- Paranoia

- Depression; and even

- Suicidal behaviors

From academics to Supreme Court Justices, and even the United Nations, the use of solitary confinement has drawn substantial criticism and is widely considered inhumane, especially for vulnerable groups such as the mentally ill and juveniles. But there’s another group whose lives are put in danger when they are forced to live in extreme isolation – older incarcerated people.

Because older adults are more likely to have chronic health conditions such as heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and lower respiratory disease, solitary confinement puts their long-term physical and mental wellbeing in danger. For the 73% of incarcerated people over 50 who report experiencing at least one chronic health condition, solitary confinement is especially hazardous.

Until now it’s been difficult to pin down exactly how many older adults are forced into solitary confinement each year, but a new report provides some answers. Based on survey data from 41 states, researchers from Yale and the Association of State Correctional Administrators find that over 6,400 men and women age 50 and older are living in some form of restrictive housing on any given day. (The survey’s definition of restricted housing includes all individuals housed in their cells for 22 hours per day or more for at least 15 days.)

But while 6,400 people is substantial, this number is just a snapshot and doesn’t reflect all of the older incarcerated people who have experienced the harm of solitary during a particular year. Using two Bureau of Justice Statistics reports, I estimate that more than 44,000 people 45 and older experience solitary in state prisons each year.1 This is more than the entire prison populations of countries like Canada, Australia, and El Salvador.

The obvious conclusion is that solitary isn’t some rarely used method of punishment, only used for younger, more threatening “offenders”. It’s the norm – even for older folks.

The effects of solitary on older people can be dangerous. According to Dr. Brie Williams of the University of California, solitary confinement increases the risk that older incarcerated people will develop or exacerbate chronic health conditions:

- A lack of sunlight can cause vitamin D deficiencies and greater risk of fractured bones

- Sensory deprivation from prolonged confinement in an empty room can worsen mental health and lead to memory loss

- Limits on space hinder mobility, which is crucial for maintaining health through exercise.

Unfortunately, there is no publically available data on why people are put into solitary, nor do we have good information on specific conditions and outcomes related to the practice. This data shortage is, in large part, because prison officials do not want their widely-used strategy to be studied in the light.

Luckily, people are beginning to take notice. Last year, spurred by public campaigns against the practice, President Obama banned the use of solitary confinement for juveniles and people who commit low-level infractions in federal prisons. But these limited reforms have not translated into widespread changes in the way we treat incarcerated people who are older and thus more susceptible to health problems.

We know that around 2,000 people age 55 and over die in state prisons each year and that upon release the formerly incarcerated are at greater risk of death due to cardiovascular disease and suicide compared to non-incarcerated individuals. Putting a population that is less likely to recidivate in conditions that contribute to these statistics is counterproductive at best. Going forward, it’s crucial that we think about how practices such as solitary confinement contribute to mortality statistics and poor health outcomes both within prisons and during the reentry process.

For the 95% of incarcerated people who will eventually return to communities across the nation, solitary confinement almost guarantees that they do so as less healthy individuals. This affects state and local resources beyond the costs of incarceration; the health costs of older adults are expected to rise substantially in the coming years, most of which will be paid for through taxpayer funded health programs. Viewed from a public health perspective, subjecting thousands of aging individuals to prolonged periods of immobility and isolation is dangerous and strains our medical infrastructure.

It’s time that state prison officials consider abolishing solitary, especially for older incarcerated people, similar to what lawmakers in New Jersey intended with S51 last year. The people we imprison aren’t lab rats (although treating animals this way is widely considered immoral), they are human beings who will be released back into society someday. Abandoning the practice of solitary is the next crucial step to chip away at the human and public health costs of mass incarceration.

Johnson and Raphael (2009) conclude that if it weren’t for the racial disparity in male incarceration, Black women would have lower rates of HIV infection than white women.

Johnson and Raphael (2009) conclude that if it weren’t for the racial disparity in male incarceration, Black women would have lower rates of HIV infection than white women.