Two more states have opted to help safe drivers get their lives back on track after drug convictions.

by Aleks Kajstura,

August 29, 2018

Two more states have stopped suspending driver’s licenses for drug offenses unrelated to driving, one of the most counterproductive policies to emerge from the War on Drugs. In January, this law was still on the books in 12 states and D.C. But with D.C.’s reversal in February and Utah and Iowa following suit, the number is now just 10, suggesting that this remains one of the most winnable justice reforms of the moment.

This marks great progress since the release of our report Reinstating Common Sense, which tracks the growing number of states rejecting this outdated and ineffective federal policy. We found that suspending the licenses of safe drivers makes the roads more dangerous, wastes law enforcement resources, and inhibits people with previous involvement in the criminal justice system from fulfilling personal, familial, and legal obligations.

These odd laws were a product of the War on Drugs, when states were eager to pile on any sort of penalties for drug offenses. In 1991 Congress started supporting automatically suspending driver’s licenses for drug offenses, and states (and D.C.) jumped on the idea.

The decades since have proven that such tactics are ineffective as deterrents. And not only do these laws not work, but they actually cause harm: Suspending driver’s licenses for non-traffic offenses decreases public safety on the road while increasing recidivism for those affected. So at the very least, taxpayers are spending a lot of money on making themselves less safe.

The remaining 10 states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Michigan, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Virginia) still suspend over 175,000 licenses every year, so there’s ample room for improvement. Which states will take this common-sense step next?

It's complicated enough for judges to weigh the influence of youth in their decisions. A new paper argues that algorithmic risk assessments may further muddy the waters.

by Wendy Sawyer,

August 22, 2018

Imagine that you’re a judge sentencing a 19-year-old woman who was roped into stealing a car with her friends one night. How does her age influence your decision? Do you grant her more leniency, understanding that her brain is not yet fully developed, and that peers have greater influence at her age? Or, given the strong link between youth and criminal behavior, do you err on the side of caution and sentence her to a longer sentence or closer supervision?

Now imagine that you’re given a risk assessment score for the young woman, and she is labelled “high risk.” You don’t know much about the scoring system except that it’s “evidence-based.” Does this new information change your decision?

For many judges, this dilemma is very real. Algorithmic risk assessments have been widely adopted by jurisdictions hoping to reduce discrimination in criminal justice decision-making, from pretrial release decisions to sentencing and parole. Many critics (including the Prison Policy Initiative) have voiced concerns about the use of these tools, which can actually worsen racial disparities and justify more incarceration. But in a new paper, law professors Megan T. Stevenson and Christopher Slobogin consider a different problem: how algorithms weigh some factors — in this case, youth — differently than judges do. They then discuss the ethical and legal implications of using risk scores produced by those algorithms to make decisions, especially when judges don’t fully understand them.

For their analysis, Stevenson and Slobogin reverse engineer the COMPAS Violent Recidivism Risk Score (VRRS),1 one of the leading “black box”2 risk assessment tools. They find that “roughly 60% of the risk score it produces is attributable to age.” Specifically, youth corresponds with higher average risk scores, which decline sharply from ages 18 to 30. “Eighteen year old defendants have risk scores that are, on average, twice as high as 40 year old defendants,” they find. The COMPAS VRRS is not unique in its heavy-handed treatment of age: The authors also review seven other publicly-available risk assessment algorithms, finding all of them give equal or greater weight to youth than to criminal history.3

To a certain extent, it makes sense that these violent recidivism risk scores rely heavily on age. Criminologists have long observed the relationship between age and criminal offending: young people commit crime at higher rates than older people, and violent crime peaks around age 21.

But for courts, the role of a defendant’s youth is not so simple: yes, youth is a factor that increases risk, but it also makes young people less culpable. Stevenson and Slobogin refer to this phenomenon as a “double-edged sword” and point out that there are other factors besides youth that are treated as both aggravating and mitigating, such as mental illness or disability, substance use disorders, and even socioeconomic disadvantage. While a judge might balance the effects of youth on risk versus culpability, algorithmic risk assessments treat youth as a one-dimensional factor, pointing only to risk.

In theory, judges can still consider whether a defendant’s youth makes them less culpable. But, Stevenson and Slobogin argue, even this separate consideration may be influenced by the risk score, which confers a stigmatizing label upon the defendant. For example, the judge may see a score characterizing a young defendant simply as “high risk” or “high risk of violence,” with no explanation of the factors that led to that conclusion.

This “high risk” label is both imprecise and fraught, implying inherent dangerousness. It can easily affect the judge’s perception of the defendant’s character and, in turn, impact the judge’s decision. Yet in all likelihood, the defendant’s age could be the main reason for the “high risk” label. Through this process, “judges might unknowingly and unintentionally use youth as a blame-aggravator,” where they would otherwise treat youth as a mitigating factor. “That result is illogical and unacceptable,” the authors rightly conclude.

This is not some hypothetical: Even when these algorithms are made publicly available, many judges admit they don’t really know what goes into the scores reported to them. Stevenson and Slobogin point to a recent survey of Virginia judges that found only 29% are “very familiar” with the risk assessment tool they use; 22% are “unfamiliar” or “slightly familiar” with it. (This is in a state where the risk scores come with explicit sentencing recommendations.) When judges rely on risk scores but are unaware of what and how factors affect those scores, chances are good that their decisions will be inconsistent with their own reasoning about how these factors should be considered.

The good news is that this “illogical and unacceptable” result is not inevitable, even as algorithmic risk assessment tools are being rolled out in courts across the country. Judges retain discretion in their use of risk scores in decision-making. With training and transparency — including substantive guidance on proprietary algorithms like COMPAS — judges can be equipped to thoughtfully weigh the mitigating and aggravating effects of youth and other “double-edged sword” factors.

Stevenson and Slobogin provide specific suggestions about how to improve transparency where risk assessments are used, and courts would be wise to demand these changes. Relying upon risk assessments without fully understanding them does nothing to help judges make better decisions. In fact, risk assessments can unwittingly lead courts to make the same discriminatory judgments that these tools are supposed to prevent.

Using a national data set, we find that over half of the people held in jail pretrial because they can't afford bail are parents of minor children.

by Wendy Sawyer,

August 15, 2018

Every day, 465,000 people are held in local jails even though they have not been convicted; legally, they are presumed innocent. Many are there because they cannot afford the money bail bond set for them. The harms of pretrial detention are well-known, both for defendants and for the juridictions that lock them up. But what about the harms of pretrial detention for families?

Previous research has estimated the number of incarcerated parents and the number of children who have parents behind bars. It’s a bit trickier, however, to estimate how many of these families are impacted specifically by pretrial detention or, even more specifically, by unaffordable money bail. We set about to answer this question.

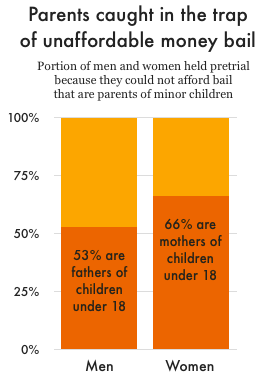

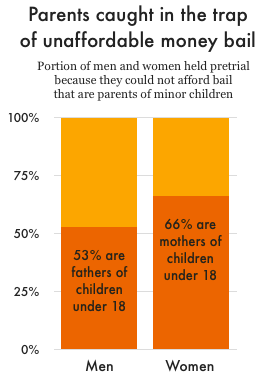

We analyzed the most recent Survey of Inmates in Local Jails to find that over half of the people in jail who could not make bail were parents of children under 18. Of the women who could not meet bail conditions, two-thirds were mothers of minor children, while just over half of the men were fathers. (See a table with all of our findings below.) Although this survey was last conducted in 2002, it remains the most recent national data on the subject available.

These results are generally consistent with national estimates of parents in the prison population. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) reports that 52% of people in state prison and 63% of those in federal prison were parents of minor children in 2007, although the share of mothers among women in pretrial detention is slightly greater than among women in prison.

Two smaller but more recent studies suggest that the impact of pretrial detention on families may be even greater than the two national BJS surveys indicate. Because of their small sample sizes, these studies are not generalizable, but they offer a glimpse of the how changes in jail populations may have impacted families since 2002, when the national data was last collected. In particular, since 2000, pretrial detention has increased by 31% to make up about two-thirds of the overall jail population, while the number of convicted people held in jail has actually fallen. Over the same 16 years, the jail incarceration rate for women has risen 26% while the rate for men has fallen by 5% — a significant trend when we consider that women are more often the primary caregivers of children.

First, in a 2016 study, researchers from George Mason University surveyed pretrial defendants, including both defendants who were detained because they did not post money bond and those who were released to pretrial supervision. Their analysis found that 56% of the detained defendants were parents. Alarmingly, 40.5% of those in this study said that pretrial detention would change — or already had changed — the living situation for a child in their custody. An additional 16.5% didn’t know whether it would change their child’s living situation.

The Robina Institute recently published the results of a 2017 study of parents in Minnesota jails and their children, finding an even greater proportion of jailed parents. Although the study did not distinguish between the pretrial and sentenced populations, it found that 69% of adults in local jails were parents of minor children. This study adds an additional detail missing in most others: 6% of the mothers reported being pregnant, and 9% of the fathers reported having a pregnant partner.

One missing, but essential data point is the number of children separated from a parent because of unaffordable bail. Our analysis of the 2002 survey data shows that at the time of the survey, over 150,000 children had a parent in jail because they couldn’t afford their bail bond. That means more children than adults were impacted by unaffordable money bail. Because of the significant changes in the jail population since 2002, we won’t attempt to extrapolate what the number of impacted children might be today. But as pretrial detention has grown, the number of children harmed by parental incarceration because of the money bail system has almost certainly grown, too.

Our analysis of the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Survey of Inmates in Local Jails (2002), including all people who had bail bond set and said they were not released on bond because they could not afford it. Estimates are based on a sample and have been rounded. For more details, see the methodology section of our report Detaining the Poor, which focused on the same population.

|

Estimated number with bond set that could not afford bond |

People with no children under 18 (percent) |

Parents of children under 18 (percent) |

Lived with children before incarceration (percent of parents) |

Estimated number of minor children |

| Men |

115,000 |

47% |

53% |

39% |

131,000 |

| Women |

13,000 |

34% |

66% |

50% |

20,000 |

| Total |

128,000 |

46% |

54% |

40% |

151,000 |

Special thanks to Board member Dan Kopf for his help with the data.

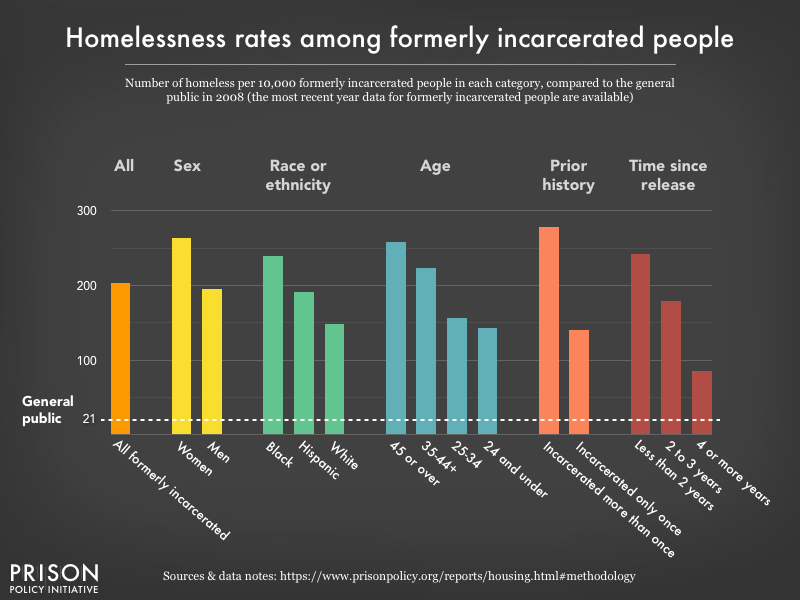

A stable home is all but required for successful reentry. How many formerly incarcerated people are locked out of housing?

August 14, 2018

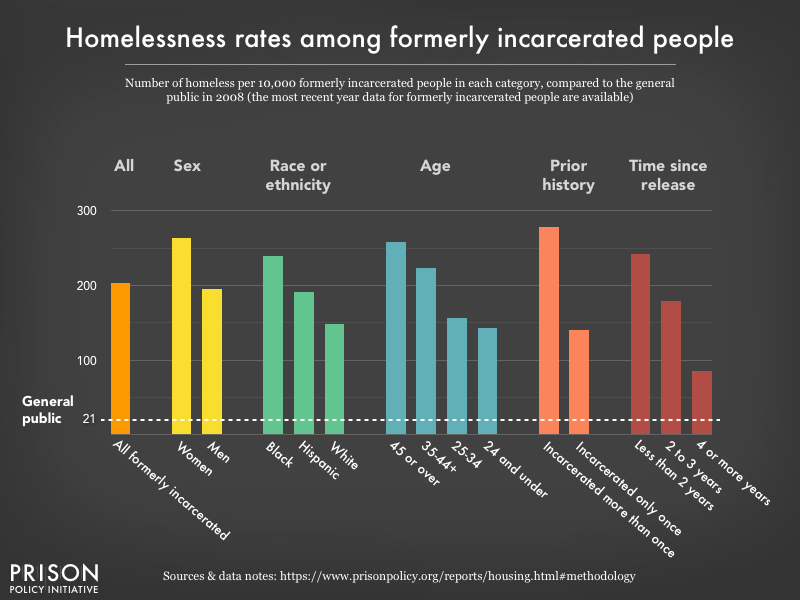

Easthampton, Mass. – People who have been to prison are 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public, according to a new report. In Nowhere to Go, the Prison Policy Initiative provides the first national snapshot of homelessness among formerly incarcerated people, which it calls a “little-discussed housing and public safety crisis.”

The report explains how people returning from prison – who need stable homes to overcome the difficulties of reentry – are nevertheless excluded from housing:

- Over 2% of formerly incarcerated people are homeless, and nearly twice as many are living in precarious housing situations close to homelessness;

- The risk of homelessness increases the more times one has been to prison – an irony considering that police departments regularly arrest and jail the homeless;

- People recently released from prison are most at risk of being homeless, with rates nearly 12 times higher than the general public;

- Women – and Black women in particular – are especially at risk.

Report author Lucius Couloute explains that landlords and public housing authorities “have wide discretion to punish people with criminal records long after their sentences are over.” Couloute lays out policy solutions to what he calls a “fixable” problem, including:

- Regulating competitive housing markets to prevent blanket discrimination;

- Creating statewide reentry systems to help recently-released Americans find homes;

- Ending the criminalization of homelessness in U.S. cities;

- Expanding social services for all homeless people, with a “Housing First” approach.

Today’s report is the second of three to be released by the Prison Policy Initiative this summer, focusing on the struggles of formerly incarcerated people to access employment, housing, and education. Utilizing data from a little-known and little-used government survey, Couloute and other analysts can describe these problems with unprecedented clarity. In these reports, the Prison Policy Initiative recommends reforms to ensure that formerly incarcerated people – already punished by a harsh justice system – are no longer punished for life by an unforgiving economy.

As our research as shown, companies like JPay gouge people who are already overcharged and underpaid.

by Wanda Bertram,

August 8, 2018

In prison, you can be overcharged to send an email – something tricky to explain to people on the outside. On Marketplace this week, Victoria Law breaks down how companies like JPay have managed to turn email into a paid service.

JPay’s service is cheap, Law says, “but not necessarily a great deal.” As we’ve explained in the past, JPay gouges people who earn almost nothing, and who are already overcharged for services like medical care.

Below is the transcribed radio interview in full:

- Kai Ryssdal:

- A lot of people probably heard of a company called JPay for the first time last week. It’s a technology company, in a way, that operates in prisons in more than 20 states, but it was the Idaho State Correctional System that made headlines after 364 inmates hacked into JPay’s system to steal $225,000 worth of JPay services. Victoria Law has been covering JPay for WIRED and we got her on the phone for a bit more on this story. Welcome to the program.

- Victoria Law:

- Thanks for having me.

- Kai Ryssdal:

- So explain to me a little bit, would you, what this service is that JPay provides.

- Victoria Law:

- JPay provides a number of services. One of those services is “e-messaging,” which is a rudimentary form of email. So if you think about email, say back in the early to mid 1990s, it’s that kind of email, where it’s plain text. You can’t say go from your email to Google or Facebook or something else. JPay charges a fee which they call a “stamp” per page, and a page is roughly 500 words. So if you were, say, to send a long letter, you would have to buy multiple “stamps.”

- Kai Ryssdal:

- Right. And it replaces, in theory, phone calls – of which there has been much in the news of late about how they’re being made more expensive by Bureau of Prisons policy – but also I imagine regular old snail-mail, right?

- Victoria Law:

- Yes. For many people, JPay even though it is expensive, it is still cheaper than the price of a prison phone call, which can be anywhere from $.20 or $.21 per minute to as much as $18 for a 20-minute phone call.

- Kai Ryssdal:

- Wow!

- Victoria Law:

- So JPay is still cheaper, but it is not necessarily a great deal. If you think about the postal service, you can put your letter plus three photos of a family reunion or a new baby into an envelope, throw a stamp on it, throw in the mailbox and that’s it. With JPay you would have to pay for the letter, and then for each photo individually.

- Kai Ryssdal:

- There are probably no consumer satisfaction surveys for JPay…But do you know, what the inmates think about it versus the way it used to be?

- Victoria Law:

- First of all, JPay, when it contracts with a state prison system, that is the only company that has e-messaging.

So it’s not like on the outside where if you don’t like Yahoo or whatever, you go to Gmail, you either use the contracted e-messaging company whether it is JPay or one of its competitors, or you don’t use e-messaging at all.

So for many people they use it because that is their only choice, but they also note that, say, if their family member is elderly or doesn’t have a computer, it then makes it much more difficult to communicate because prisons that have contracted with JPay have also used this as an opportunity to cut down on the kinds of mail that people can get.

- Kai Ryssdal:

- A word here about the cost of these things, of this service rather, and you lay it out pretty well in this article, but $.47 inside a prison is not the same as $.47 outside the prison.

- Victoria Law:

- No, you have to remember that the majority of people in prison, if they are working a job in the prison, make something around $0.12 an hour. That money has to pay for not only things like JPay, but also necessities like aspirin – or in many prisons they charge a co-pay for a medical visit. So it falls largely upon the family members of people who are inside jails and prisons to cover these costs.

- Kai Ryssdal:

- Victoria Law writing about JPay most recently in WIRED. Her book about part of the prison complex in this country is called Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women. Victoria, thanks a lot for your time. I appreciate it.

- Victoria Law:

- Thanks for having me.

Stories about prison tablets are becoming more common. We offer tips to newsrooms for covering this issue fairly.

by Wanda Bertram,

August 2, 2018

This month, while we were uncovering the hidden costs of JPay’s “free” prison tablets, people incarcerated in Idaho were discovering something else: a way to “hack” JPay’s software to transfer credits to their own accounts.

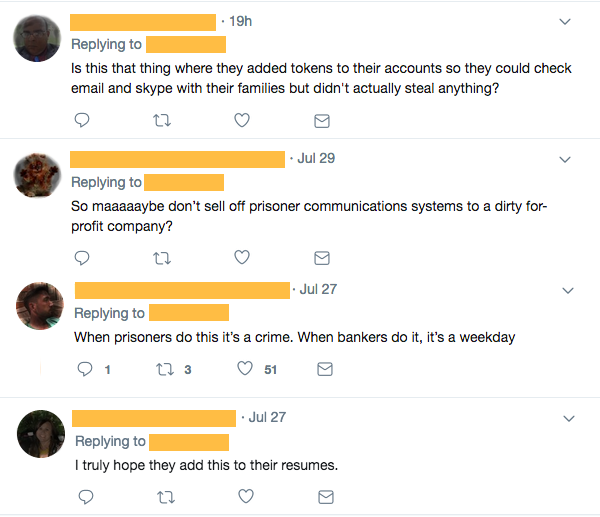

It’s never certain how a story like this will be covered in the news, or how readers will react. But on Twitter, readers overwhelmingly sympathized with the “hackers” behind bars:

We tip our hats to readers who intuitively put this story into perspective. However, some news sites missed the point, with headlines like “Prison inmates hacked into tablets to steal nearly a quarter-million dollars,” or “Inmates ‘Hack’ Prison-Issued Tablets, Swiping $225,000 in In-App Bucks for Music and Games.”

For newsrooms covering prison tablets, we have some suggestions:

- Be wary of describing prison retailers the way they describe themselves. A company that “provides inmates with access to the outside world” at no cost to taxpayers sounds good, but what if that company sustained itself by grossly overcharging people in prison?

- If you’re talking about credits, don’t say “dollars.” A “quarter-million dollars” in tablet credits buys a lot less than you’d expect (see #3 and #4).

- Explain that the credits aren’t just for music and games. People in prison are also charged for video chats, email and money transfer – things that cost you and me almost nothing. Most of the Idaho hackers gifted themselves $1,000 in credits (or less). That amount – at least in other states whose contracts we’ve studied – buys less than 60 hours of video chat.

- Don’t forget to explain that these systems are unlike anything in the free world. The economy for digital services in prison is broken, with prisons often offering monopoly contracts to providers that will charge customers the most.

Finally, a general tip for covering the prison business: Talk to incarcerated people and their loved ones. For those forced to use JPay, the big story may not be the “exploitation” of vulnerable software, but the company’s ongoing exploitation of vulnerable families.