Our analysis reveals that at least 4.9 million people cycle through county jails each year - and most have serious medical and economic needs.

August 26, 2019

Police and jails are supposed to protect the public from serious public safety threats, but what do they actually do? Until now, attempts to answer this question have been missing the most basic data points: how many individuals cycle through local jails every year and who these individuals are.

A new report from the Prison Policy Initiative, Arrest, Release, Repeat, fills this troubling gap in the data. Building on its popular annual snapshot of the U.S. county jail population, the Prison Policy Initiative finds that:

- At least 4.9 million people are arrested and booked in jail every year.

- At least 1 in 4 people who go to jail in a given year will return to jail over the course of a year.

- At least 428,000 people will go to jail three or more times over the course of a year – the first national estimate of a population often referred to as “frequent utilizers.”

“4.9 million people go to jail every year — that’s a higher number than the populations of 24 U.S. states,” said report co-author Alexi Jones. “But what’s even more troubling is that people who are jailed have high rates of economic and health problems, problems that local governments should not be addressing through incarceration.”

The report reveals that:

- 49% of people with multiple arrests in the past year had annual incomes below $10,000, compared to 36% of people arrested only once and 21% of people with no arrests.

- Despite making up only 13% of the general population, Black men and women account for 21% of people who were arrested just once and 28% of people arrested multiple times.

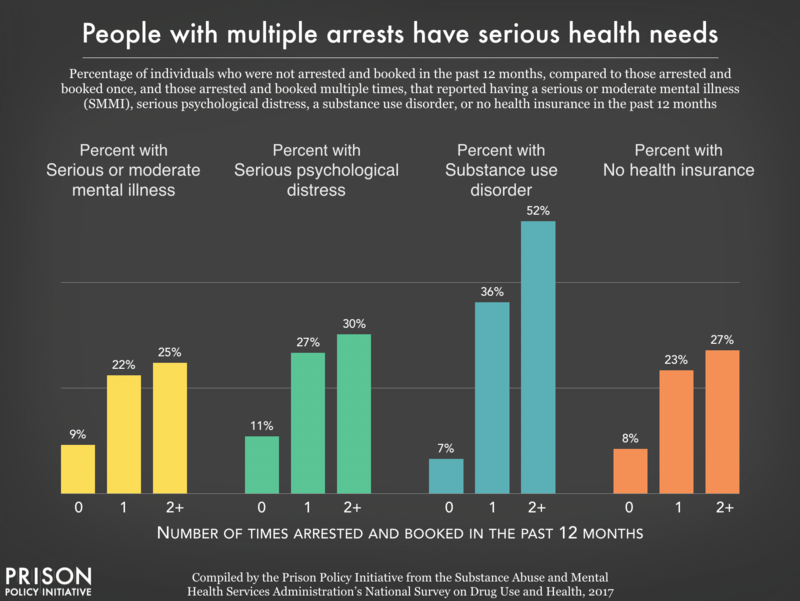

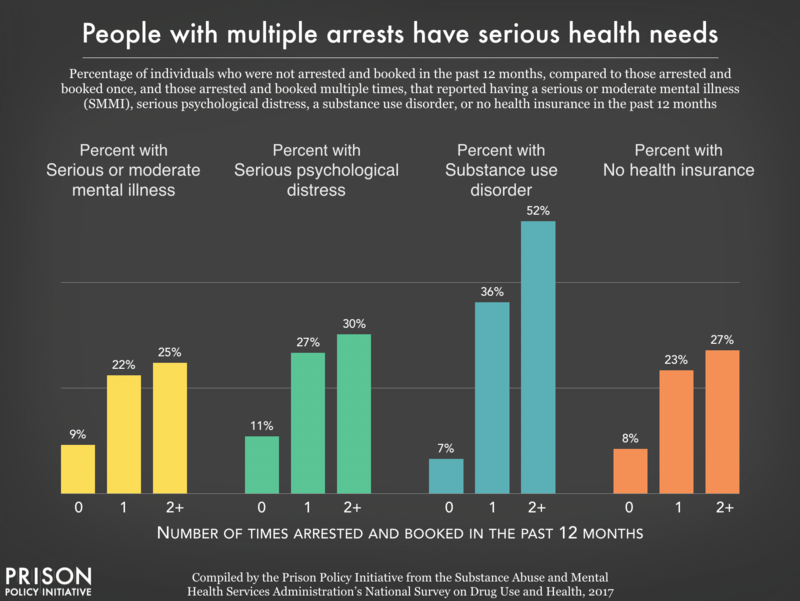

- People with multiple arrests are much more likely than the general public to suffer from substance use disorders and other illnesses, and much less likely to have access to health care.

- The vast majority of people with multiple arrests are jailed for nonviolent offenses such as drug possession, theft or trespassing.

In a series of policy recommendations, the report explains how counties can choose to stop continuously jailing their most vulnerable residents and instead solve the economic and public health problems that often lead to arrest. “Counties should stop using taxpayer dollars to repeatedly jail people,” said report co-author Wendy Sawyer, “and use the savings to fund public services that prevent justice involvement in the first place.”

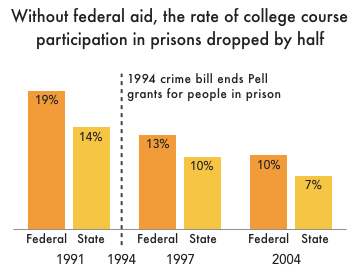

Without federal aid, the rate of college course participation in prisons dropped by half.

by Wendy Sawyer,

August 22, 2019

Journalists, policymakers, and advocates frequently ask us to answer tricky but important questions about the criminal justice system. Until now, however, many of our answers to these common questions have gone unpublished, gathering dust in our email archives. This post is the first in what we anticipate will be an ongoing “Since You Asked” series that makes our answers to these important questions public. (Want to send us your questions? Use our contact page.)

Q: How many people participated in college-in-prison programs before and after the 1994 crime bill? (And how many participate in prison education programming today?)

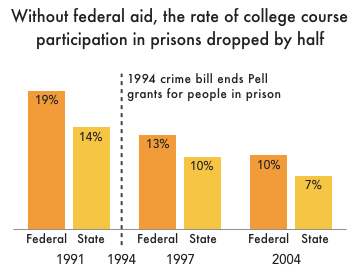

A: To understand the drop in college participation in prisons following the 1994 “crime bill,” it’s important to know that most in-prison college programs, unlike colleges and universities in the “free world,” largely depend on funding from the Pell Grants program and other federal aid programs. This is largely because incarcerated people are overwhelmingly poor and can neither afford college tuition nor make generous gifts as alumni.

According to a historical overview by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), prisons “witnessed a surge in demand for college courses” after the passage of the Higher Education Act of 1965, a law that greatly expanded federal aid for college participation nationwide. By 1982, 350 college-in-prison programs enrolled almost 27,000 prisoners (9 percent of the nation’s prison population), primarily through Pell Grants. … By the early 1990s, it is estimated that 772 programs were operating in 1,287 correctional facilities across the nation.”

A 1992 amendment to the Higher Education Act made people serving life sentences without parole and those sentenced to death ineligible to receive Pell Grants. Then, the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act banned everyone incarcerated in prisons from receiving Pell aid, even though these grants made up less than 1 percent of total Pell spending. “By 1997,” the AEI briefing continues, “it is estimated that only eight college-in-prison programs existed in the United States.” The remaining programs were those that received financial and volunteer support from other sources.

According to the American Historical Association, “States followed by further blocking access to funds through regional programs.” In 2005, the New York Times Magazine wrote that there were “about a dozen” prison college-degree programs, “four of them in New York State.”

The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) 2003 publication Education and Correctional Populations includes some data that reflects these changes (see Table 4). In 1991, 13.9% of people in state prisons, and 18.9% of those in federal prisons, had taken a college course since admission. By 1997, these numbers had dropped to 9.9% for people in state prisons, and 12.9% in federal prisons. The 2004 BJS Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities (variable V2503) shows that the downward trend continued: In 2004, just 7.3% of respondents in state prisons had taken a college-level class since admission.

More recently, results from a 2014 study of people in prison found that 2% of respondents had completed an Associate’s degree while incarcerated, and 1% had completed a Bachelor’s degree or higher. Notably, 58% of respondents reported that they had not completed any further education while incarcerated.

But these statistics do not reflect a lack of interest in higher education among people in prison: To the contrary, 40% of respondents to the survey said that they would like to enroll in an Associate’s or Bachelor’s degree program, and an additional 29% wanted to enroll in a postsecondary certificate program. Nor are most people in prison unqualified for such programs: A recent report from the Vera Institute of Justice and Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality analyzed the same survey results and found that “the majority of incarcerated people are academically eligible for postsecondary-level courses.”

As we’ve previously found, educational exclusion is a strong predictor of incarceration in the U.S. But federal and state governments are far from powerless to repair the harm that results. Restoring Pell Grants to incarcerated people would make approximately 463,000 people in prison eligible for free college courses.

It’s time for the government to not only restore this critical aid, but expand it.

by Bernadette Rabuy,

August 9, 2019

In case you missed it, John Oliver exposed the high fees and low wages pervasive in prisons and jails on last Sunday’s episode of Last Week Tonight.

Oliver cited our research to shine a light on the low wages — or no wages, in the case of Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia and Texas — that incarcerated people receive for their hard work.

Despite the low wages paid to people in prison, Oliver explained, prisons squeeze money out of incarcerated people and their families by forcing them to pay for basic needs, such as:

- Hygiene products: Too often, prisons do not provide sufficient hygiene products and incarcerated people are forced to buy additional items on their own dime. We found, for instance, that the average person in an Illinois prison spends $80 a year on toiletries and hygiene products.

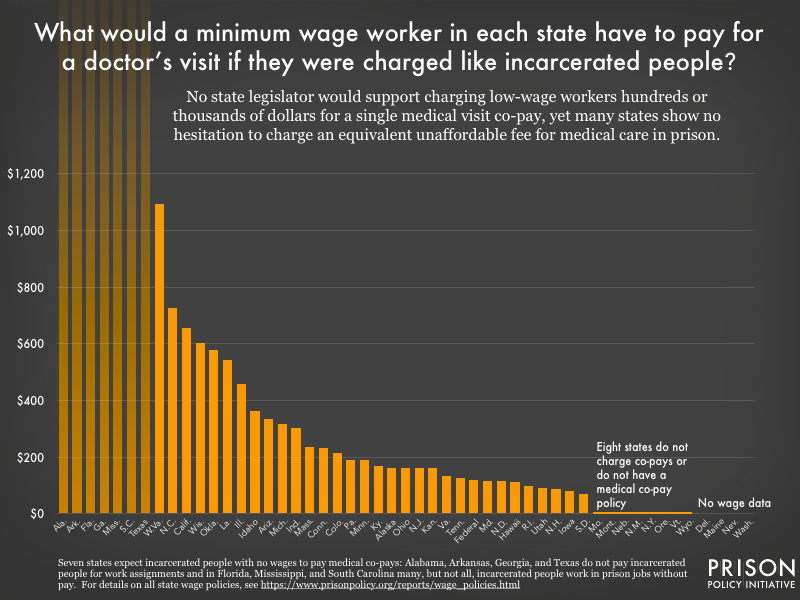

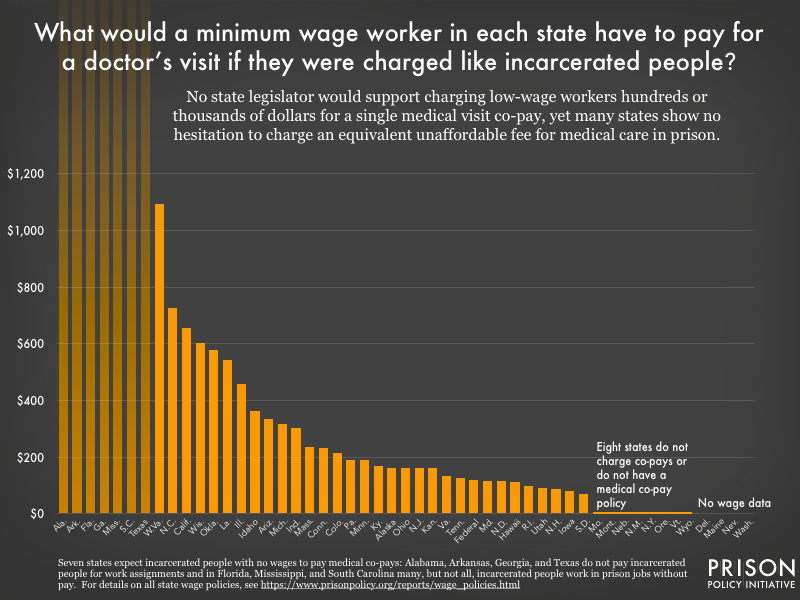

- Copays for medical visits: Our 2017 state-by-state analysis revealed that fourteen states charge co-pay amounts equivalent to charging minimum wage workers over $200.

- Video calls: Oliver scrutinizes the high cost of video calls and the harmful trend of jails replacing in-person visits with video chats. Oliver states that a video call system is really a “machine that makes money by stopping people from visiting their families,” which is surely “an item at the top of Satan’s Amazon wish list.”

Oliver also shared his skepticism of correctional officials’ claims that banning in-person visits is justified because it reduces contraband. Oliver pointed out that contraband often enters correctional facilities through other channels, such as through staff.

“Part of the way mass incarceration persists in this country is by keeping the true costs of it off the books,” Oliver concludes. We couldn’t agree more. Thank you, Last Week Tonight, for helping us expose these harmful practices!

Three states have taken action in 2019 to change one of the most harmful policies in prison healthcare.

by Wanda Bertram,

August 8, 2019

Prison healthcare is almost always a depressing topic, but not today, when we can report an important victory: Illinois recently became the third state in 2019 to reform the practice of charging medical co-pays to incarcerated people.

Previously, we published a state-by-state analysis showing that most prisons charge medical copays to people inside – despite the fact that their patients are impoverished and earn little to no money for their work in prisons. Using prison and free-world wage data, we calculated what each state’s co-pay would cost if it was charged to free-world patients making the minimum wage. Our analysis revealed that fourteen states charge co-pay amounts equivalent to charging minimum wage workers over $200.

Policy details and sourcing information can be found in the Appendix of our original analysis.

Policy details and sourcing information can be found in the Appendix of our original analysis.

Charging co-pays to incarcerated people to shore up a state’s correctional budget is simply wrong. In our analysis, we explained that not only does this policy squeeze poor people and their families; it hurts public health by making the choice to seek medical attention a costly one.

We’re glad to see that states are now paying attention and taking action:

- Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker signed a bill in July eliminating the state’s $5 co-pay. Previously, people working in an Illinois state prison (where the minimum wage is 9 cents per hour) would have had to work for over 55 hours to afford the $5 fee. That’s like charging a non-incarcerated minimum-wage earner in Illinois over $460. In some cases, incarcerated people paid even more before getting adequate care, because paying the fee didn’t guarantee a doctor visit – only that a nurse would review one’s medical request.

- Earlier this year, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation announced that it would stop charging a $5 medical co-pay to incarcerated people. CDCR’s press release acknowledged what advocates have long known: Charging co-pays is bad for public health. “Copayments,” it said, “may hinder patients from seeking care for issues which, without early detection and intervention, may become exacerbated.” The department’s decision came as the California legislature was considering AB 45, a bill to eliminate medical co-pays in both state prisons and county jails. AB 45 (for which we wrote a letter of support) continues to move through the state legislature.

- The Texas legislature stopped short of eliminating medical co-pays in prisons entirely, but made progress by replacing the notorious $100 fee Texas had charged incarcerated people with a $13.55 per-visit fee. While this change marks a substantial improvement, incarcerated people in Texas – who earn nothing for their labor – will continue to be charged the highest medical co-pay in state prisons nationwide.

State reforms like these can’t come soon enough. As we noted in our 2017 analysis, out-of-reach co-pays in prisons and jails have two inevitable and dangerous consequences. First, when sick people avoid the doctor, disease is more likely to spread to others in the facility – and into the community, when people are released before being treated. Second, illnesses are likely to worsen as long as people avoid the doctor, which means more aggressive (and expensive) treatment when they can no longer go without it.

It’s welcome news that states are finally taking action to change this risky and regressive policy. Will your state be next?

Policy details and sourcing information can be found in the

Policy details and sourcing information can be found in the