Can you help us sustain this work?

Thank you,

Peter Wagner, Executive Director Donate

COVID-19 in Prisons and Jails

America's response to the COVID-19 pandemic in prisons and jails was a failure. This page provides a recap of our work during this tragic time.

July, 2024

With more than half a million infections behind bars and over 3,000 deaths, America’s response to COVID-19 in prisons and jails was a failure. Federal, state, and local governments ignored public health guidance, refused to implement even the most basic mitigation strategies, and failed to reduce their incarcerated populations to the level necessary to avoid these catastrophes.

The COVID-19 national emergency may be over, but the ramifications of the nation's failed response to it will be felt for years.

Prison and jail crowding has deadly consequences

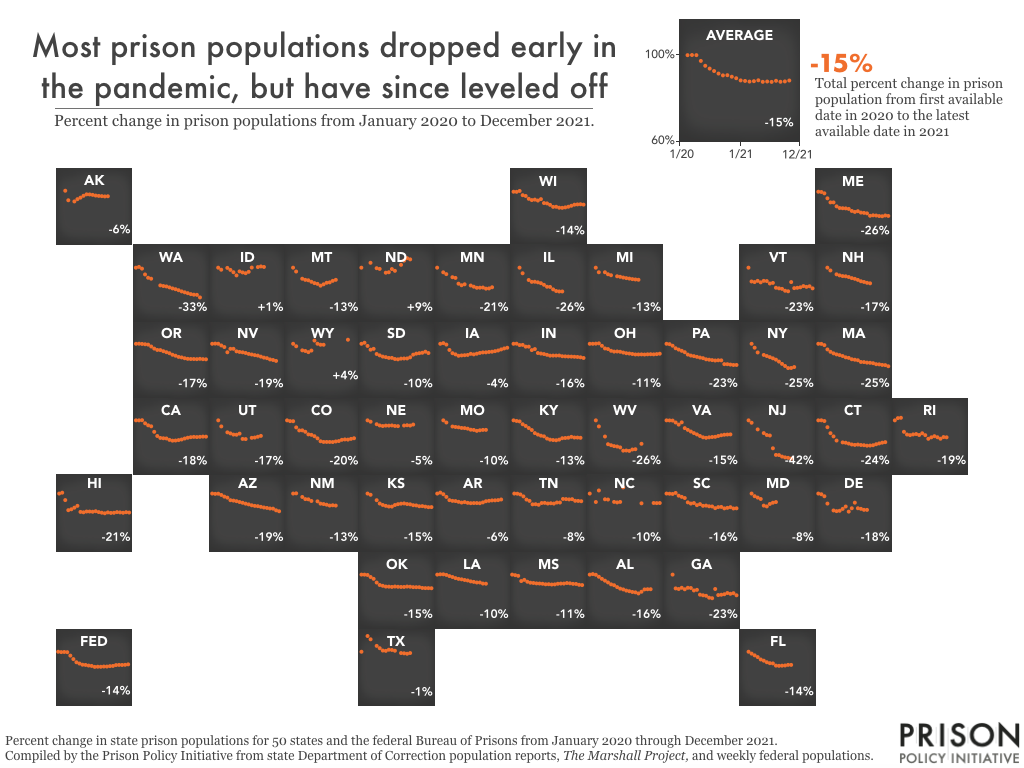

From the beginning of the pandemic, it was clear, the most effective way to mitigate the devastation of COVID-19 in prisons and jails is to reduce the number of people behind bars. The United States locks up a larger portion of its population than any other nation in the world. While it is true that the incarcerated population is lower than it was at the beginning of the pandemic, it is still far too high and trending back up.

When the pandemic struck, it was instantly obvious what needed to be done: take all actions possible to “flatten the curve.” This was especially urgent in prisons and jails, which are dense facilities where social distancing is impossible, sanitation is poor, and medical resources are limited. Public health experts warned that the consequences were dire: prisons and jails would become Petri dishes where, once inside, COVID-19 would spread rapidly and then boomerang back out to the surrounding communities with greater force than ever before. There were widespread calls for governments to decarcerate. Unfortunately, these calls went unanswered.

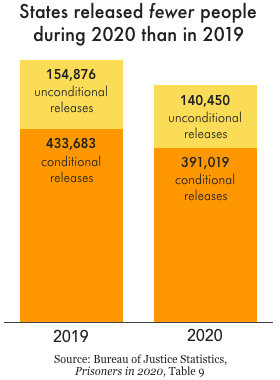

Despite initial hopes that leaders would respond to the pandemic by releasing people, on the whole prisons released almost no one. Only three states — New Jersey, California, and North Carolina — released a significant number of incarcerated people from prisons. Parole boards also approved fewer releases in the first year of the pandemic than the year before. The response of governments was so bad that, in total, 10% fewer people were released from prisons and jails in 2020 than in 2019. As a result, at the end of the first year of the pandemic, 19 state prisons systems were at 90% capacity or higher. Even states that reduced prison populations didn’t necessarily reach “safe” population levels (if any prison can be called “safe”). At the end of 2020, 1 in 5 state prison systems were at or above their design or rated capacity. And there is plenty of evidence that these numbers have gotten worse since then.

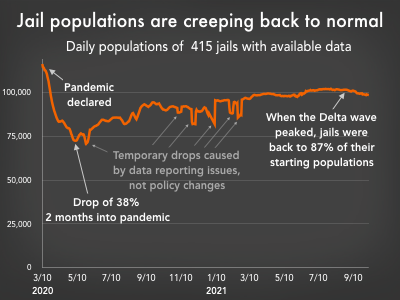

Jail populations dropped early in the pandemic, mostly due to reduced admissions. However, as the pandemic drug on, jail populations steadily climbed, nearly back to their pre-pandemic levels.

Jails were particularly ill-prepared to respond to the pandemic. People generally don’t stay in jails for extended periods. There is a constant churn of people entering and leaving, creating a significant public health threat to people on both sides of a jail’s walls. Much like prisons, jails also saw an initial decline in their populations due to reduced admissions. As the pandemic drug on, though, jails populations slowly approached their pre-pandemic levels.

So, if governments failed to undertake the large-scale releases necessary to confront a pandemic, how is it possible that the incarcerated population is lower now than it was in 2019?

Reductions in the number of people in our nation’s prisons were not the result of goodwill for incarcerated people, concern for their health and safety, or a concerted effort to end mass incarceration. Instead, they were primarily an unintended consequence of court delays and suspension of transfers from local jails early in the pandemic. Many of the same factors that snarled our nation’s supply chain and made it more difficult to get appointments for various services also slowed down the process of sending people to prison.

These delays were temporary, though. As governments adapted to the virus, they quickly returned to business as usual, and prison and jail populations began creeping back up.

The failure to reduce incarcerated populations had ripple effects that worsened the pandemic far beyond the prison walls. At the onset of the pandemic, areas with higher incarceration rates experienced significantly higher COVID case rates. Our analysis showed that in the summer of 2020, mass incarceration resulted in half a million more cases nationwide. The study revealed that not only do prisons not improve public safety, but they also harm public health.

America also failed to effectively roll out vaccines in prisons. Despite the clear evidence that incarcerated people — like others living in close quarters — were at heightened risk from the virus, most states did not give people in prison the highest priority access to vaccines. In addition, states rarely took proactive steps to address vaccine-hesitancy behind bars. As a result of these two failures, vaccine updating in prisons — for both incarcerated people and corrections officers — consistently lagged behind the nation.

COVID-19 showed why our nation must abandon its addiction to mass incarceration. While the worst of the COVID pandemic appears to be over, the criminal legal system must change to ensure that a short stint in jail or prison does not become a de facto life sentence.

Looking for something you saw on this page before? See an archived list of items that used to be on this page.