Prison disciplinary fines only further impoverish incarcerated people and families

We analyzed prison policies for all 50 states and the federal prison system, and found that 16 prison systems actually impose fines — in addition to other punishments — when someone violates a prison rule. We explain why disciplinary fines and fees are bad policy, putting excessive hardship on incarcerated people and their loved ones.

by Leah Wang, February 7, 2024

In yet another example of how the criminal legal system extracts wealth from the poorest families, at least one-third of prison systems nationwide charge fines as a punishment for a rule violation. Prison administrators claim that imposing disciplinary fines, along with other punishments, helps to maintain order and reduce violence in correctional facilities. They also argue that the fines simulate outside-of-prison processes for dealing with misconduct, such as parking tickets.

Though rule violations1 and their corresponding sanctions are a common feature of incarceration, disciplinary fines and fees aren’t the way to create safe environments where people can prepare for their release. On the contrary, when prisons impose these charges and subsequently help themselves to the funds in people’s prison accounts, incarcerated people are often left with little to no money for purchasing essential items and services that the prison doesn’t provide.2 As a result, their mental and physical health suffers, creating a more volatile environment inside. Loved ones also pay the price of these fines — often literally, as a primary source of financial support.

Like medical “co-pays” and exceedingly low wages in prison, disciplinary fines and fees are little more than a means to exploit incarcerated people. Whether they’re tiered fines or flat “administrative” fees, they are an undue burden; prison is already one big financial sanction for those who are already on the lowest rungs of the economic ladder. By focusing on punitive measures that deprive people further, prisons miss the mark on what actually makes prisons safer — providing opportunity rather than taking it away. We hope advocates and policymakers will understand how disciplinary fees, which exist alongside other excessive punishments, undermine the rehabilitative goals of corrections, the safety of people inside, and the odds of success during reentry.

Disciplinary fines and fees are used in about one-third of all prison systems

To determine just how common disciplinary fines and fees are, we combed through the publicly available policies on prison disciplinary procedures in each state and the federal prison system. We also looked at policies related to prison-controlled bank accounts (often called “inmate trust accounts”) and related fees, as well as practices relating to collecting debts. We found that at least 16 prison systems charge incarcerated people disciplinary fines or fees:

Prison disciplinary fines and fees

| Source | Jurisdiction | Range of fines | Violation types | How is money collected? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR 403 Procedures for Inmate Rule Violations | Alabama | No more than $500 | Having a social networking account | |

| AR 403 Procedures for Inmate Rule Violations | Alabama | $25.00 “processing fee” | Possession of cell phone | |

| 803 Inmate Disciplinary Procedure | Arizona | $500 to $2000 | First, second, or third violations of types (02A, 03B, 05A, 16A, AND 19A) which include assault on staff, unauthorized access, having a communication device | |

| 5270.09 Inmate Discipline Program | Federal (BOP) | Up to $50, or 12.5% of trust fund balance | Low severity level | |

| Federal (BOP) | Up to $100, or 25% of trust fund balance | Moderate severity level offense | ||

| Federal (BOP) | Up to $300, or 50% of trust fund balance | High severity level offense | ||

| Federal (BOP) | Up to $500, or 75% of trust fund balance | Greatest severity level offense | ||

| Authorized Disciplinary Sanctions List | Georgia | $100 “administrative processing fee” | Charge D-3(j), having a cell phone or similar device allowing communication with the outside | Account is temporarily frozen pending the outcome of disciplinary proceedings; if person is found guilty, account is permanently frozen for the amount ordered and a check for the amount ordered is written if enough funds exist. No account deductions are made below an account balance of $10. |

| 201.04 Inmate Accounts | Georgia | $4 fee | Any infraction | |

| Major Discipline Report Procedures | Iowa | $5 fee | In addition to any other medical costs assessed, the fee is imposed for trips to the Univ. of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (UIHC) or a local hospital caused by an incarcerated individual’s self-injurious behavior, willful neglect, etc. | |

| Conduct and Penalties | Kansas | Up to $10 | Class III (least serious) offense | |

| Kansas | Up to $15 | Class II offense | ||

| Kansas | Up to $20 | Class I (most serious) offense | ||

| 20.1 Prisoner Discipline | Maine | At least $5 | Any violation (Class A – C) | |

| Maine | Up to $100 | Class A (most serious) violation, specifically for assault on a non-incarcerated person, “deadly instrument,” gang-related or substance-related violations | ||

| 3.4.1 Institutional Discipline | Montana | $1 to $50 | Certain major violations (codes specified in policy) | |

| Montana | $1 to $30 | First, second, or third instances of certain major violations (codes specified in policy) | ||

| Montana | Unspecified “fine” | A minor violation | ||

| 4932 Standards Behavior & Allowances | New York | $5 “surcharge” | Any infraction | |

| B.0200 Offender Disciplinary Procedures | North Carolina | $10 “administrative fee” | Any class of offense A-D | |

| Facility Handbook (2021) | North Dakota | “Financial sanctions” including fees and/or fines | Level III (most serious) sanction | Funds may be withdrawn without a signature to meet financial obligations; all available money in spending account will be applied. If the obligation is greater than what’s available in account, future pay and money received by outside sources are garnished. If unable to pay debts owed at release from custody, the debt will remain active should individual return to custody. |

| Major Violation Grid | Oregon | $25 to $200 | Major violations (specific codes listed in policy) | |

| 502.02 Disciplinary Punishment Guidelines | Tennessee | $3 | Class C offense (only assessed if three Class C offenses occur in a 30-day period) | Funds are withdrawn from account anytime balance exceeds zero. Individual with confirmed rule violation will be required to fill out a form authorizing withdrawal. Presumably, funds are withdrawn even if they refuse to sign the form, but policy does not state this explicitly. |

| Tennessee | $4 | Class B offense | ||

| Tennessee | $5 | Class A offense | ||

| FD01 Inmate Discipline | Utah | $20 to $300 | Class B violation | |

| Utah | $150 to $600 | Class A violation | ||

| 861.1 Discipline | Virginia | Up to $15 | Category II (less serious) offense | |

| Virginia | Up to $25 | Category I (more serious) offense | ||

| 3.101 Code of Inmate Discipline | Wyoming | Up to $5 | Minor violation | |

| Wyoming | up to $10 | General or major violation |

Every jurisdiction that charges disciplinary fines or fees does so a bit differently, but taken together, a few findings stand out:

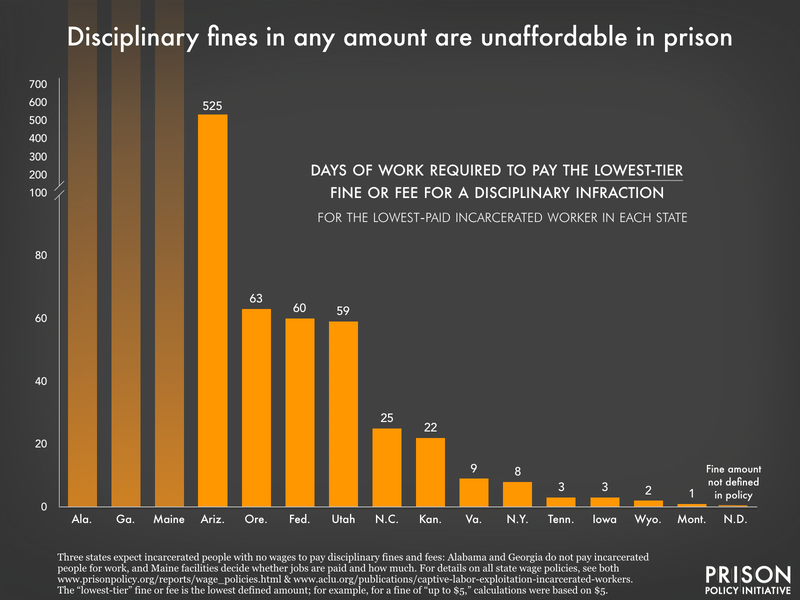

- Disciplinary fines and fees are common. In 16 prison systems, we found policies referencing fines and/or fees related to confirmed disciplinary violations (where someone is found guilty or pleads guilty). In many cases, the severity level3 of the rule violation determines the amount of the fine, but in other cases there is a “flat” charge for any violation. In either case, charging fines means that some of the most innocuous behaviors — like making “loud or disturbing noises” in Kansas prisons — have a price tag.

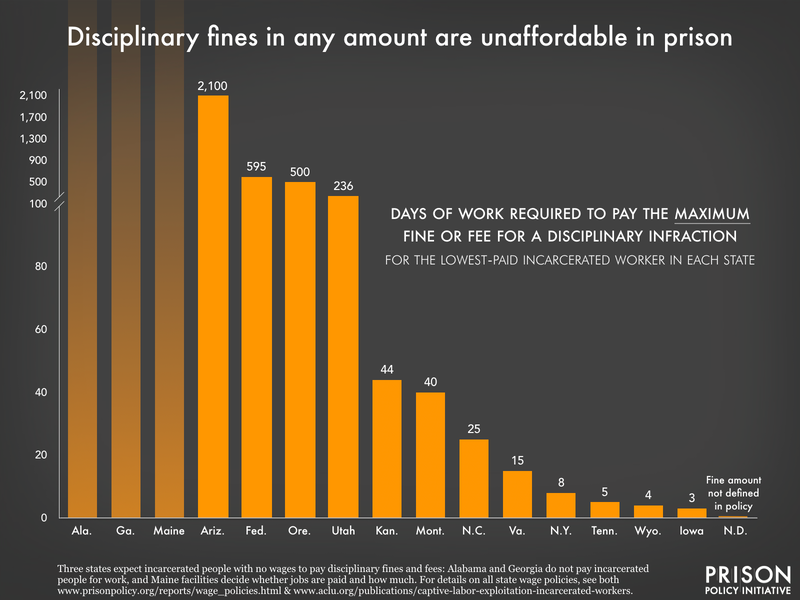

- Most prison systems impose disciplinary fines between $5 and $25, but some charge hundreds or thousands of dollars. Incarcerated people in five jurisdictions (Alabama, Arizona, Maine, Oregon, Utah, and the federal prison system) can face triple-digit fines for a single disciplinary charge: For example, Arizona’s fines start at a shocking $500 for the first instance of what they consider the most serious violations4 and go as high as $2,000. Utah state prisons impose up to $600 for a more serious “A Code” offense, and up to $300 for a “B code” offense — which can be for things like “horseplay,” or any conduct deemed “disorderly.”

- Some prison systems insidiously present these charges as “administrative” fees. We found five prison systems that charge “administrative” or “processing” fees for disciplinary violations. We include them here because they’re just as punitive and unaffordable as fines. In Georgia, for example, each guilty finding for a disciplinary violation comes with a $4 fee, unless the violation is for having a cell phone or similar communication device, a harshly-punished violation in several states;5 that specific act will set someone back a $100 “administrative processing fee.” People incarcerated in North Carolina prisons, who are charged a $10 administrative fee per disciplinary infraction, collectively lost $313,000 in fees to the state’s general fund in Fiscal Year 2022 alone.6

For incarcerated people, even “small” fines and fees can be huge setbacks

Outside of prison, a $5 or $10 fine might seem pretty inconsequential, or even surprisingly low. (Parking tickets, for example, are generally much more costly.) But to a typical person behind bars, a loss like this represents a serious change in financial circumstances; the value of money is simply different in prison. Prisons charge people for necessities like food and hygiene products, communication with loved ones, health care, and in some cases, “room and board.”7 And prison wages hardly cover these expenses, averaging less than one dollar per hour in most jurisdictions:

- Someone in Kansas, for example, would have to work for over two months in the lowest-paying prison job to pay off a $20 disciplinary fine, the maximum charged there.8

- In Virginia, where any rule violation comes with a flat $15 fine, it could take 33 to 55 hours (or one to two weeks) of work to cover that cost. Of course, this math only applies to the roughly 50% of the prison population with jobs; those earning no wages have to rely on financial support from loved ones. 9

It’s also important to note that prison disciplinary and labor systems already disadvantage some more than others: Black and Indigenous people, women, and those with disabilities10 tend to face prison discipline disproportionately. And research shows racial, gender and disability disparities in how prisons assign jobs. Considering disciplinary fines in this context, it makes little economic or administrative sense to continue picking these pockets.

Almost all prison systems also order restitution, but some states’ policies are excessive and inappropriate

We also found that nearly all prison systems have a policy about facility-owed restitution, or the reimbursement of costs incurred for damaged property or medical expenses that result from a rule violation. We often think of restitution as court-ordered reimbursement to civilian crime victims — and many incarcerated people face this type of debt, too — but in a prison setting, restitution serves as little more than a running tab for the state.

Many prison restitution policies require that the amount being sought reflects the actual cost of an item or service, like the requirement to present an “itemized list of expenses and/or items damaged and costs to repair or replace” in Georgia state prisons. Such efforts to justify restitution amounts might sound reasonable to an outsider, but these “reimbursements” are to state agencies for largely budgeted costs.11 For example, some prison systems pursue restitution for things like staff overtime, vehicle mileage, and workers’ compensation costs.12 13 And in a shameless move only the carceral system could devise, four states (Iowa, Georgia, Nevada, and New Mexico) seek reimbursement for medical charges related to self-harm and/or suicide. The financial cost of events that happen in prisons, which are inherently violent and mentally damaging places, shouldn’t be billed to incarcerated people and their families.

Prison systems often help themselves to the money they charge incarcerated people

In order to collect monetary sanctions, prisons will garnish (deduct) a portion — in some cases, up to 100% — of money credited to an incarcerated person’s account, whether it’s their hard-earned wages, money transfers from loved ones, or economic stimulus payments.14

A common deduction rate we found in our survey of state policies was 50%: Seven states (Iowa, Kentucky, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, California, and Rhode Island) deduct up to half of incoming deposits and apply it to a debt. That means, for example, that someone with a disciplinary fine debt in Pennsylvania who earns 50 cents per hour (near the maximum prison wage there) would only receive 25 cents per hour. Some of these states further complicate matters by just taking everything: Rhode Island prisons will begin collection on a debt by taking as much of the amount owed as possible, leaving an account balance of $10, and then begin garnishing 50% of subsequent deposits to cover the rest. This means that money sent in by a loved one may never actually reach its intended recipient, but instead go straight into the prison’s pocket.

A few other states’ policies (Oregon, Texas, and Wisconsin) suggest that 100% of funds are garnished (sometimes referred to as a “freeze” on an account) to cover a debt, without leaving any amount to cover basic necessities. And while nearly all prison systems claim to provide assistance to people who are extremely poor, or “indigent,” we found that prison indigence policies are too narrowly defined and limited to be very helpful.

Prison debt collection policies can also apply post-incarceration: Some prisons hold debts like disciplinary fines or facility-owed restitution on file in case of a future return to custody. And a few cases we found, corrections departments turn into collection agents — or at least threaten to do so: In Iowa prisons, for example, if someone who owes has signed an agreement, staff may pursue debts in small claims court or by seeking to garnish their state tax refunds. In Wisconsin, transfer or release “shall not terminate the inmate’s obligation to pay ordered restitution.” It’s hard to know whether prison systems actually enforce these collection policies, but the possibility looms large over people who work hard to be truly free of prison once they’re released.

Disciplinary fines and fees are just one part of an illegitimate ‘kangaroo court’ system in prisons

Disciplinary fines and fees are only a microcosm of a much larger problem with how prisons treat behaviors and “discipline.” The comprehensiveness of prison policies on rules, sanctions, collecting debts, and disciplinary hearings might suggest that prisons offer incarcerated people transparency and due process when they’re accused of a rule violation, but evidence suggests the opposite.

In fact, incarcerated people are not entitled to many aspects of due process when it comes to disciplinary hearings, like calling witnesses and obtaining counsel. Further, disciplinary hearings in prisons only require “some evidence” (in other words, any small amount of evidence) of misconduct, a much lower standard of proof than courts require in outside legal decision-making.15 This arbitrary and shadowy adjudication process only leads to hurt and mistrust; take this scenario, based on a case observed in a 2015 study of prison discipline:

A male prisoner tosses a plastic cup half-full of liquid toward a prison officer, nearly hitting her…. [T]he result, almost inevitably, will be cellular confinement (segregation) and a loss of privileges of some sort… During this time, the prisoner’s anger at the officer will potentially increase, exacerbated by the painful conditions of solitary lockdown. When the prisoner returns, he or she will make life difficult for the officer and the officer may in turn make life difficult for the prisoner. The cycle continues.

The legitimacy and credibility of prison disciplinary hearings — or lack thereof — matter because the stakes can be high. Being found guilty of a more serious violation, in particular, can change the course of someone’s incarceration drastically, through solitary confinement, the loss of earned good time, restricted access to necessary commissary items, and the potential impact on parole decisions. Prison systems should consider how this “kangaroo court” system of disciplinary hearings unfairly and harshly punishes people for behaviors that, as mounting evidence suggests, are often brought about by the prison environment itself. When harm does occur inside, restorative justice practices present an alternative way to problem-solve, and could lead to a more trusting, safer climate.

Disciplinary fines and fees in prisons are not “accountability”

While they may imitate the broader “justice” system in some ways, disciplinary fines and fees arguably do nothing to promote a sense of accountability or safety inside of prisons. The current approach to handling prison misconduct, in which fines play just a supporting role, is infantilizing and creates bleak conditions like solitary confinement and deprivation, which in turn lead to violence and mental health problems. To make prisons safer for everyone, administrators should overhaul disciplinary processes and provide more access to and opportunities for family contact, education, healthcare, treatment, and repairing harm.

By pulling back the curtain on murky aspects of everyday prison life like discipline, we hope prison administrators and policymakers will see that incarcerated people are starved for opportunities to achieve economic, professional, and personal growth, and that disciplinary sanctions undermine these goals.

Footnotes

-

There are many terms for alleged rule violations in prisons: tickets, writeups, infractions, violations, disciplinary reports (or D-reports), bookings, etc. Once they are confirmed violations, through a guilty finding or plea, the corresponding punishments are typically called sanctions, or sometimes penalties. ↩

-

The punishments for rule violations in prison typically include other losses that put goods and services out of reach, such as being banned from commissary, visitation and/or phone use, and recreation for a period of time, removal from programs, solitary confinement, or confinement to one’s own cell. In states that do impose disciplinary fines, a combination of other sanctions is often handed down at the same time. ↩

-

Many prison systems have categorized rule violations in some hierarchy ranging from least to most serious, using letters, numbers, or words like “major” and “minor.” Our disciplinary policies resource page explains these categories where information is available. ↩

-

Arizona’s steep prison disciplinary fines are imposed for a strange subset of violations, which include assaults on staff (whether resulting in injury or not), arson, possession of a communication device or a component of one, and tampering with a lock or door. They’re not imposed for other instances of grave misconduct like assault on other incarcerated people, sexual assault, or possessing a weapon. ↩

-

Though having a cell phone is essential for navigating the world today, many state prisons treat possession of contraband cell phones and similar devices as one of the most serious types of misconduct, represented in some cases (like Georgia) by a heavy fine. Alabama and Arizona also come down hard on people with cell phones, at least when it comes to disciplinary fines and fees; we haven’t done a 50-state scan of states that treat this violation harshly with non-monetary sanctions. ↩

-

This figure came from the response to a public records request we filed with the North Carolina Department of Adult Corrections in October 2023. ↩

-

According to analysis from the Brennan Center, as of 2015, at least 43 states authorize room and board (or “pay-to-stay”) fees to incarcerated people. ↩

-

According to the ACLU’s report Captive Labor: Exploitation of Incarcerated Workers, the lowest wage paid to incarcerated workers in Kansas’ state prison system is just $0.45 per day; a $20 fine, then, would take 44 work days to pay off, assuming wages aren’t garnished for other reasons. ↩

-

In 2020, there were 31,838 people in Virginia state prisons, and approximately 16,000 of them were “wage-earning offenders,” earning $0.27 to $0.45 per hour in non-industry jobs. ↩

-

A report from Human Rights Watch explains in detail how incarcerated people with mental disabilities have several aspects of prison environments working against them when it comes to behavior and discipline. Many correctional officers are not trained to recognize signs of mental illness and may find certain behaviors frightening or threatening; as a result, people with mental illness are punished for disciplinary violations at higher rates than general prison populations. And when those people are placed in solitary confinement for disciplinary or other reasons, they are less likely to receive treatment and more likely to engage in misconduct (or perceived misconduct) in the future. Regarding economic status, though not covered in our own report Prisons of Poverty, people with disabilities are much more likely to live in poverty or face economic hardship compared to the average American. ↩

-

For example, the Connecticut Department of Corrections budgets included “workers’ compensation claims” as a line item until it was consolidated with other state agencies’ claims, and the Department is required to report to the legislature its “estimated costs associated with staffing deficiencies [and] overtime costs.” In another example, Arizona’s Department of Corrections budget includes “mileage – private vehicle” in several sections. See footnote 11 for similar items in Iowa’s budget. ↩

-

These are just a few things included in Iowa’s far-reaching policy on prison-owed restitution. Notably, travel, workers’ compensation reimbursement, and “state vehicle operation” appear throughout the department’s budget as budgeted expenditures. ↩

-

While it’s easy to assume that correctional employees hurt on the job are typically injured by incarcerated people (which might justify these restitution policies to some), this may not be the case. An Inspector General report investigating the New York prison system found that “from 2015 through 2021, on average, 66 percent of all workers’ compensation injury claims did not involve contact with an incarcerated person. That is, year after year, on average, the number of claimed injuries not involving contact with an incarcerated person is almost double those injury claims that do.” ↩

-

Prison debt collection policies exist even in jurisdictions that don’t charge disciplinary fines, because they collect other fees not related to discipline, and collect debt on behalf of other agencies, like court systems. ↩

-

The standard of proof used in legal decision-making is called a “preponderance of the evidence,” which means proving that something is more likely than not to be true. ↩

Excellent, this info is being moved around a group of college students with an interest in getting involved further…some working on PhDs in specific social health/welfare

I am involved in a minimum security prison (started in 97) and just last week some of the guys in my group were talking about tablets and email (restricted) and apps for movies can be loaded….one told me that he spends over $40 a month plus $400 a month for food and phone services (somemtimes $500 easily when weather locks you down)-of course the largest funding comes from family on the outside………..so my question follows who is making money on the inmates…..thanks

Hey Robert, thanks for passing this along to your students. FYI- we have written about the costs of prison tablets several times, most comprehensively in this 2019 briefing: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2019/03/07/free-tablets/

And there is also some discussion of tablets in our 2022 report on the far-reaching prison telecom industry. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html