New report ranks states on “correctional control,” showing huge state disparities in use of probation

December 11, 2018

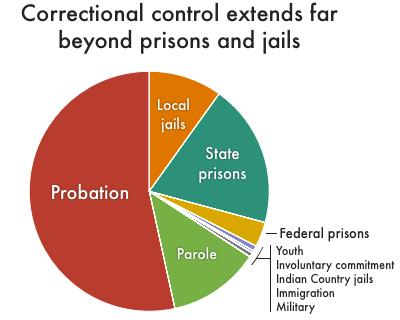

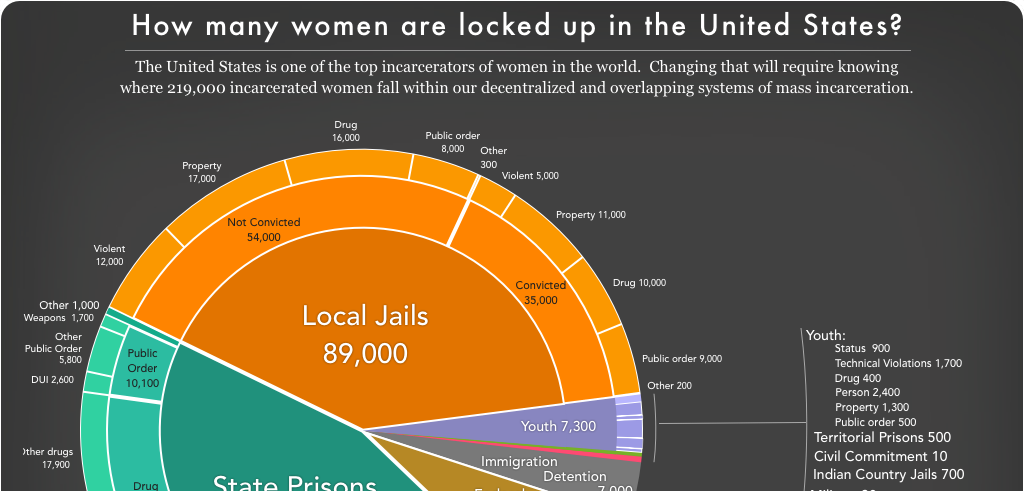

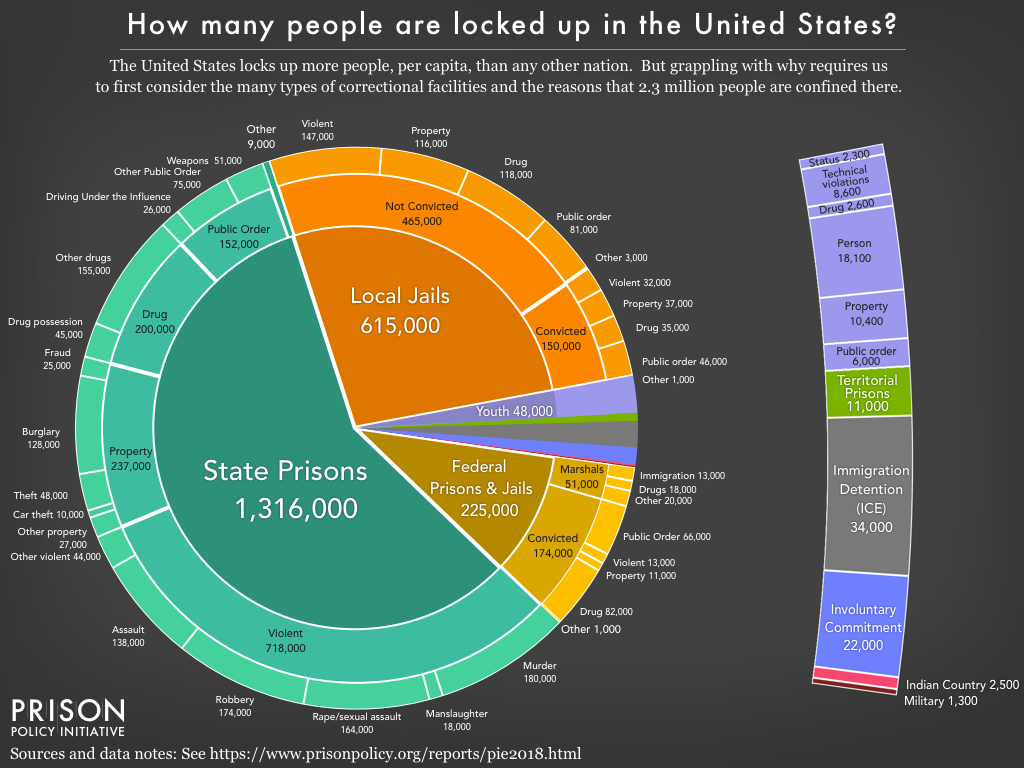

When it comes to ranking U.S. states on the harshness of their criminal justice systems, incarceration rates only tell half of the story. 4.5 million people nationwide are on probation and parole, and several of the seemingly “less punitive” states put vast numbers of their residents under these other, deeply flawed forms of supervision.

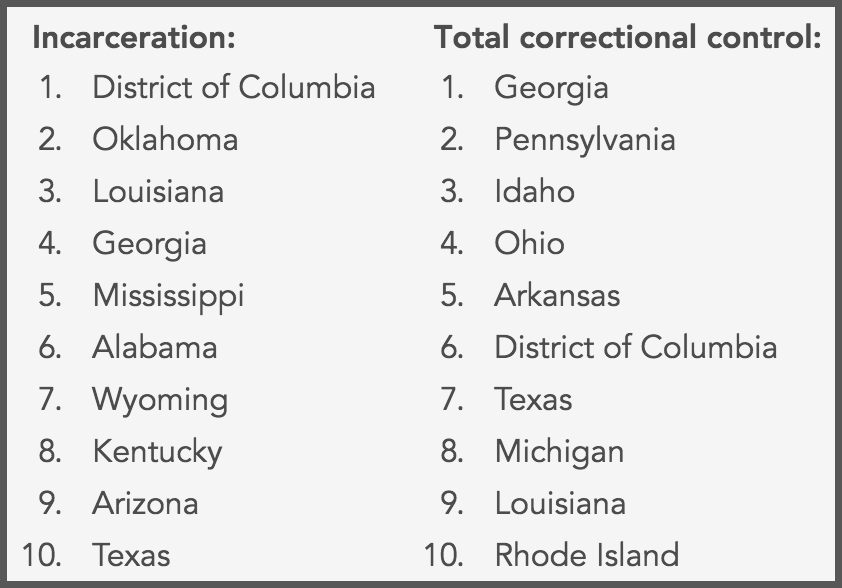

In Correctional Control: Incarceration and supervision by state, the Prison Policy Initiative calculates each state’s rate of correctional control, which includes incarceration (in all types of facilities) as well as community supervision (probation and parole). The report includes over 100 easy-to-read charts breaking down each state’s correctional population.

The report also includes an interactive chart that ranks states on their use of correctional control, with surprising findings including:

- Ohio and Idaho surpass Oklahoma – the global leader in incarceration – in correctional control overall.

- Pennsylvania – which famously revoked Meek Mill’s probation last year – has the second-highest rate of correctional control in the nation.

- Rhode Island and Minnesota have some of the lowest incarceration rates in the country, but are among the most punitive when community supervision is accounted for.

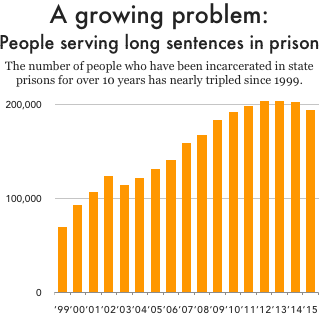

Many of the highest rates of correctional control are in states with high rates of probation. “All too often,” says report author Alexi Jones, “probation serves not as a true alternative to incarceration but as the last stop before prison.” Jones proposes specific reforms and highlights the flaws in current probation systems:

- Probation imposes time-consuming conditions and fees that people struggle to meet, and which can paradoxically hold them back from turning their lives around.

- Violating even the most minor of these requirements (such as missing a meeting) can result in incarceration.

- Probation terms can go on for years after the original offense, meaning even model probationers can serve decades under state scrutiny.

But probation is malfunctioning in even more fundamental ways, explains Jones: “States are putting people on probation when a fine, warning, or community treatment program would suffice,” thereby putting more people at risk of incarceration.

“It’s obviously better to keep people in the community than to incarcerate them,” says Jones. “But states need to ask the hard questions about their supervision systems: Whether probation and parole are truly helping people get their lives back on track, and whether everyone who is under supervision really needs to be.”