We offer lessons learned from developing our new report, Shadow Budgets, to encourage journalists to investigate welfare funds in their local prison or jail systems.

by Wanda Bertram,

May 6, 2024

Our new report Shadow Budgets: How mass incarceration steals from the poor to give to the prison explains that prisons and jails squeeze revenue out of incarcerated people and their families via paid telecommunications services, commissaries, money transfers, and disciplinary fines, then funnel it into “Inmate Welfare Funds” and use the money to cover the costs of incarceration. While corrections officials claim that these funds go to benefit incarcerated people, money from these accounts often sits idle — or worse, is spent on perks for correctional staff, like special meals or gun range memberships. Even when the funds are put toward improving conditions behind bars, the spending typically meets a need that can and should be paid for out of the agency’s general budget — not money extracted from incarcerated people.

Shadow Budgets identifies welfare funds in 49 prison systems, explains what rules govern these funds, and discusses some of the ways this money has been misused. As we discuss in the report, however, inmate welfare funds are not as transparent or accountable as general correctional budgets. Outside actors like state auditors — and investigative journalists — play a key role in uncovering how states and counties use this money. In this blog post, we offer lessons learned from developing our report to encourage journalists to investigate these funds in their local prison or jail systems.

Investigating welfare funds: what records to request, and how

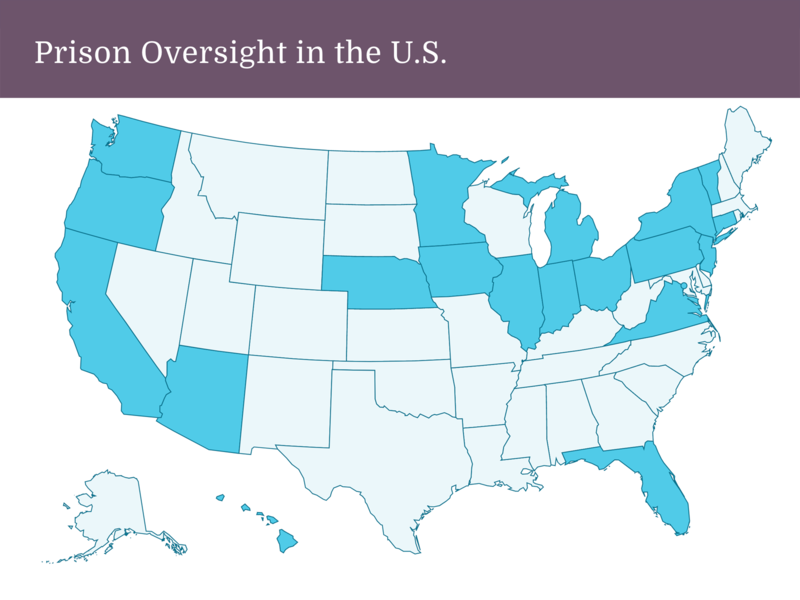

Not all jails and prisons have welfare funds, and those that do may call it something else. In some places, they don’t appear to have formal names at all. (And while most funds draw revenue from commissary and/or telecom services purchases, some may have other sources.) If Appendix A of our report doesn’t provide these details about the jail or prison system you’re investigating, you can call the agency itself and ask. You might want to ask where kickbacks from telecom and commissary services are deposited, or whether there is a fund for the general welfare or benefit of the incarcerated population. Alternatively, you can consult county, municipal or state policies (for example, this one for the Michigan Department of Corrections). Information about funds in local jails may also be listed in state correctional standards, if you live in a state where the department of corrections has authority over jails.

The most important questions you’ll investigate about the welfare fund are: How much money is in the fund, how is it being spent, and who gets to decide? You will likely have to submit a public records request to find out; for tips on filing public records requests to corrections agencies, see our records request guide.

Specifically, we recommend that you request:

- An itemized list of purchases made from the inmate welfare fund (try to go back two or three years, if possible, to get a representative dataset).

- Balance sheets for the account. As we discuss in our report, many if not most prison systems sit on large amounts of revenue even as key programs for incarcerated people go underfunded. The balance sheet will show if the jail or prison is actually using the money. Again, asking for a few years of data will help understand whether balances are carried over.

- Any audits or fiscal reports on the funds. Depending on your county and state, you may instead want to request this information from the auditor’s office, the county/city board or council, or the state department of corrections. (The state or local policies governing the welfare fund should tip you off as to what agency to reach out to about audits and fiscal reports.)

- If the fund has an oversight committee — which should be mentioned in the state/local policies discussed above — request information about how often the committee meets, when its last meeting was, and who sits on the committee. If the jail or DOC cannot provide this information, it’s possible that the committee is not active. (On the other hand, if the committee is active, consider contacting them as a source for your story.)

- You may also want information about the sources of money in the fund. In particular, we advise locating the jail/prison’s contracts with its commissary or telecom providers, where agreements about revenue-sharing are typically laid out. We’ve made hundreds of contract documents available to the public in our Correctional Contracts Library.

We also suggest asking the jail or prison whether incarcerated people have any say in how the inmate welfare fund is used. Since these funds are theoretically dedicated to benefiting incarcerated people, and are paid for by incarcerated people, it’s good to know to what extent administrators consider their input.

How to assess uses of welfare fund money

Most jails and prisons have regulations or statutes governing what the money in their inmate welfare fund may be used for. (Appendix A of our report contains details on the rules in several prison systems.) Sometimes, corrections officials use the money in ways that may violate these rules, like Pinal County, Ariz. Sheriff Mark Lamb, who spent $200,000 in revenue from jail phone calls and commissary services on “guns, bullets and vests” for law enforcement officers. John Washington of Arizona Luminaria, who broke the story, found that the state statute governing the welfare fund only allowed the money to be used for “the education and welfare of inmates.”

It’s worth noting, however, that the Pinal County Jail’s fund also paid for “recreational equipment, clothing, and internet services for people who are incarcerated.” These kinds of expenditures are legal under Arizona’s statute, but they are not laudable uses of poor people’s money. Jails have a responsibility to make sure the people in their care are clothed. And to the extent that “internet services” are necessary for people in jail to have access to law libraries and the courts, they are a constitutional right, not a privilege.

When assessing uses of welfare fund money, consider the following questions:

- Is the jail or prison forcing incarcerated people to cover the cost of their own basic needs?

- Is it appropriate to force many of the lowest-income people in the county or state (i.e. the majority of people in jail, and their families) to pay for these things?

- Why is the county or state not paying for these goods, services or programs out of its general budget?

Keep in mind that it’s not always easy to tell whether uses of these funds are legal or not. As we discuss in our report, many state statutes include wiggle words like “primarily” or “including but not limited to,” effectively giving corrections officials free rein to spend the money any way they like. Just because an expenditure is technically legal, of course, doesn’t mean it is right.

Who else to talk to

Incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people and their families

If you’re able to contact people behind bars or their loved ones, ask them whether they have heard of the inmate welfare fund (make sure to use whatever term the jail or prison uses). You can also ask if they know of any programs or benefits for incarcerated people paid for with that money.

In writing Shadow Budgets, we talked to several formerly incarcerated people and advocates for incarcerated people about their views of welfare funds. Many saw the funds as regressive and exploitative, while many also worried about them being dismantled, and were concerned that if they did not exist, the needs met with those funds would go unfulfilled. While there is no easy answer for what to do about these funds, incarcerated people’s perspectives are crucial to understanding what the funds are or are not accomplishing.

State and local elected representatives

It’s likely that many elected lawmakers will never have heard of inmate welfare funds before. Nevertheless, because the funds are governed by state and local regulations, lawmakers can and should be held accountable for inappropriate uses of the money.

We also suggest asking state elected officials broader questions about welfare funds, such as:

- Are you concerned about prisons and jails having large discretionary budgets that are outside the purview of the legislature?

- Why does the state not choose to fund these services and programs with money from the regular appropriations process?

Recommended reading: investigative journalism about inmate welfare funds

These stories focusing on or involving welfare funds may give you other ideas about questions to explore, or sources to contact for your story:

- PennLive’s 2023 investigation into the Dauphin County Jail’s use of telecom and commissary revenues (via the jail’s welfare fund)

- Pacific Sun’s 2022 reporting on the welfare fund in the jail in Marin County, California

- WSB Atlanta’s 2023 story about misuses of money in the Fulton County Jail’s welfare fund

- Arizona Luminaria’s story series about Pinal County Sheriff Mark Lamb’s use of welfare fund money to buy guns and ammunition for law enforcement

Much like other aspects of prisons and especially of local jails, inmate welfare funds are rich territory for journalistic investigations because they have so little transparency. Unless state or local lawmakers request visibility into these funds, they can be spent more or less however correctional officials wish, meaning that hundreds of millions of dollars in public spending nationwide is virtually unaccounted for. By investigating welfare funds, journalists can shine a light not only on a little-known form of public spending, but also on the broader priorities of jail and prison officials. Transparency into these funds can spark important conversations about whether these officials’ stated commitment to incarcerated people’s wellbeing is reflected in their use of resources.

If you’re a journalist and have any questions about our report or about this guide, please don’t hesitate to write to us through our contact page.