In our rebuttal to Securus, we disprove the company's claims of healthy competition in the prison phone market.

by Aleks Kajstura,

July 31, 2018

Two weeks ago, the Prison Policy Initiative, along with the Wright Petitioners and other advocates, called on the Federal Communications Commission to stop the merger of prison phone companies Securus and ICSolutions. Following Securus’ reply, we filed a rebuttal today demonstrating why the company should not be allowed to acquire its last effective competitor for prison and jail phone contracts.

Securus tried to argue that there’s still plenty of competition left in the market. The company quibbles over the methods we used to calculate its future market share (should it acquire ICSolutions). But the math here is not really that complicated: When a giant industry player acquires a competitor, there is immediately one less player, which reduces competition.

And competition in the prison phone market is more important than ever. Prisons and jails are finally starting to pay serious attention to the rates shouldered by incarcerated people and their families, taking these concerns into account when they choose a phone provider.

Securus, meanwhile, “continues to engage in charging unlawful and egregious rates,” as well as enabling illegal cell phone tracking. Securus is asking the FCC to look the other way as it acquires one more of its competitors. It must be prevented from expanding its frontier for misconduct.

For our detailed analysis of why Securus/ICSolutions are wrong about diversity of competition, and barriers to entry and expansion in the prison and jail phone market, see Exhibit D of our filing.

In a follow-up to our commissary report, we look at Texas commissary vendors and discover some surprising findings alongside the usual suspects.

by Stephen Raher,

July 26, 2018

One of the original inspirations for our report on prison commissaries earlier this year was a 2010 article from the Texas Tribune that analyzed $95 million in purchases at prison commissaries in the previous fiscal year. Because of the solid information already contained in the Tribune article, we chose not to use Texas as one of our sample states. But given the size of the Texas prison system, it seemed important to conduct some kind of review of commissaries in the Lone Star State.

This time, we looked at the sources of goods rather than spending patterns among incarcerated people, and discovered a couple of surprising findings alongside the usual major vendors.

The data

Using spending data available through the office of the Texas Comptroller, we were able to get a sense of where the state prison system buys commissary goods. Although there is no way to isolate commissary spending specifically, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) lists its expenditures by category. One expense category is “cost of goods sold–merchandise for resale,” and it’s a reasonable guess that all or nearly all of this spending is for commissary inventory.1 In Fiscal Year 2017, TDCJ reported $77.6 million in purchases in the merchandise-for-resale category, which is roughly in line with what one would expect to see in a system that generates around $100 million in annual sales.

Our findings

Even though the purchasing data is only broken down by general category, there are a few observations and questions that emerge:

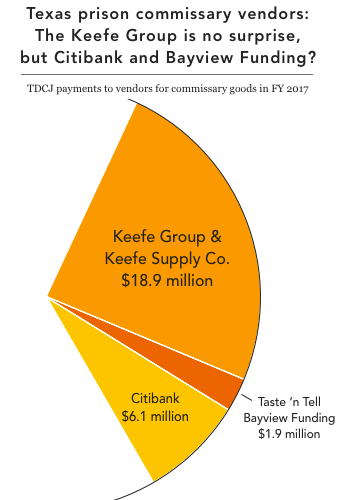

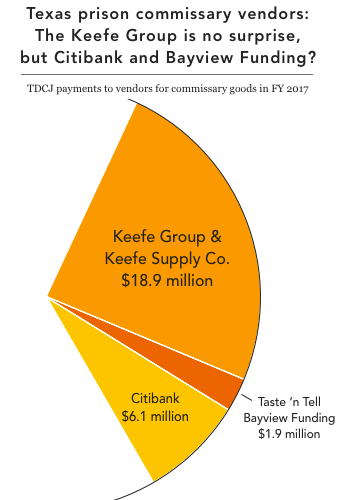

- Once again, Keefe is king. As we noted in our commissary report, even in states (such as Texas) that have not privatized commissary operations, the large commissary companies can still make money. Case in point: the largest single vendor in the data we examined was Keefe, accounting for nearly $19 million in inventory spending (about a quarter of all of TDCJ’s commissary purchases for the year).

- But why is Citibank making money on commissary too? Oddly, the third largest vendor by dollar-amount is Citibank, accounting for slightly over $6 million in purchases. This is a bit surprising, since Citibank doesn’t really sell “merchandise.” There’s no quick way to find out what this money is for – some of it could be money orders purchased by incarcerated people, but it could also be some kind of transaction fees, digital services sold to incarcerated people, or an actual product sold by Citibank. In any case, the point is: Citibank is receiving a big chunk of money from the Texas commissary system.

- And most mysterious of all, we have the curious case of Taste ‘n Tell International. Among the fifteen largest vendors in in the FY 2017 purchase data is a company called Taste ‘n Tell International, LLC, which received $1.9 million in payments from TDCJ in FY 2017. This company jumps out because it shipped goods to TDJC and issued invoices, but the state sent its payments to a financing company called Bayview Funding. This is because Taste ‘n Tell had obtained cash under a “factoring agreement” – a business financing arrangement where a financial firm (in this case, Bayview) purchases accounts receivable from an operating company (Taste ‘n Tell) at a discount from face value. Bayview makes money by pocketing the difference when the customer (TDCJ) pays.

Factoring by Taste ‘n Tell is a bad sign. Factoring is generally more expensive than traditional business financing options like bank loans. As a result, it is often used by new companies that lack a track record of profitability, or by companies in financial distress. Taste ‘n Tell is not particularly new (it was formed in 2008), but its financial affairs do look a bit rocky. Public records show that the company has been on the losing end of five lawsuits since 2012, with total judgments reaching almost $200,000. The company’s apparent owners have both filed personal bankruptcy petitions in the past, and the company’s headquarters appears to be a private residence in St. Louis.

Taste ‘n Tell’s use of factoring matters because it likely impacts the prices it charges TDCJ, which in turn impacts the prices charged to incarcerated people through the commissary. Are people in Texas prisons paying inflated prices in order to help Taste ‘n Tell get quick cash from a factoring company? That requires a closer look at what TDCJ is buying.

A sampling of invoices from FY 2017 shows that TDCJ purchases hygiene and food products from Taste ‘n Tell. Many of these items are not sold to the general public, making price comparisons difficult, but there are a couple of items that allowed us to shop around. First, in June 2017, TDCJ bought approximately 265,000 Femtex brand tampons (in cases of 480) from Taste ‘n Tell, for $45 a case (or 9¢ per tampon). The same brand of tampon retails for basically the same price on Amazon. The second example comes from June 2017 when TDCJ ordered 1,200 cases of Encore Premium garlic powder (12 bottles per case) for $9.24 a case (or 77¢ per bottle). The same brand is available for less (69¢ per bottle) to others who order in bulk from a wholesaler.

So why is Texas doing business with Taste ‘n Tell? Available data suggests that Taste ‘n Tell isn’t providing bargains. So why else would TDCJ be doing business with a small company that has a track record of not paying its bills? It’s hard to say. Perhaps Taste ‘n Tell satisfies some procurement quota for small or minority-owned businesses. Maybe the company is owned by people who have the right political connections. Or Taste ‘n Tell could actually have submitted the lowest bid.

Whatever the reason, the Taste ‘n Tell example is another reminder that commissary customers can’t hunt for the best price–they are captive to purchasing managers who often end up signing off on head-scratching deals like the Taste ‘n Tell purchases.

There's no such thing as a free lunch - or a free tablet.

by Wanda Bertram and Peter Wagner,

July 24, 2018

If someone offered you a free computer, you’d rightly be suspicious that there were strings attached. So when private companies offer “free” tablets to incarcerated people, politicians are understandably skeptical, looking for hidden costs to the state.

But in their quest for an answer, politicians will often fail, as we saw in New York State earlier this year. Private company JPay signed a contract with the New York Department of Corrections to give free tablets to 52,000 incarcerated people. Facing questions from legislators, the department insisted – truthfully – that taxpayers wouldn’t pay a dime.

Legislators dropped the issue without asking the bigger question: What would motivate a company to give away 52,000 tablet computers for free?

We filed a public records request, and got a more complete answer: The 52,000 “free” tablets are part of a package deal (or “bundled contract”) of several JPay services that gouge incarcerated people and their families.

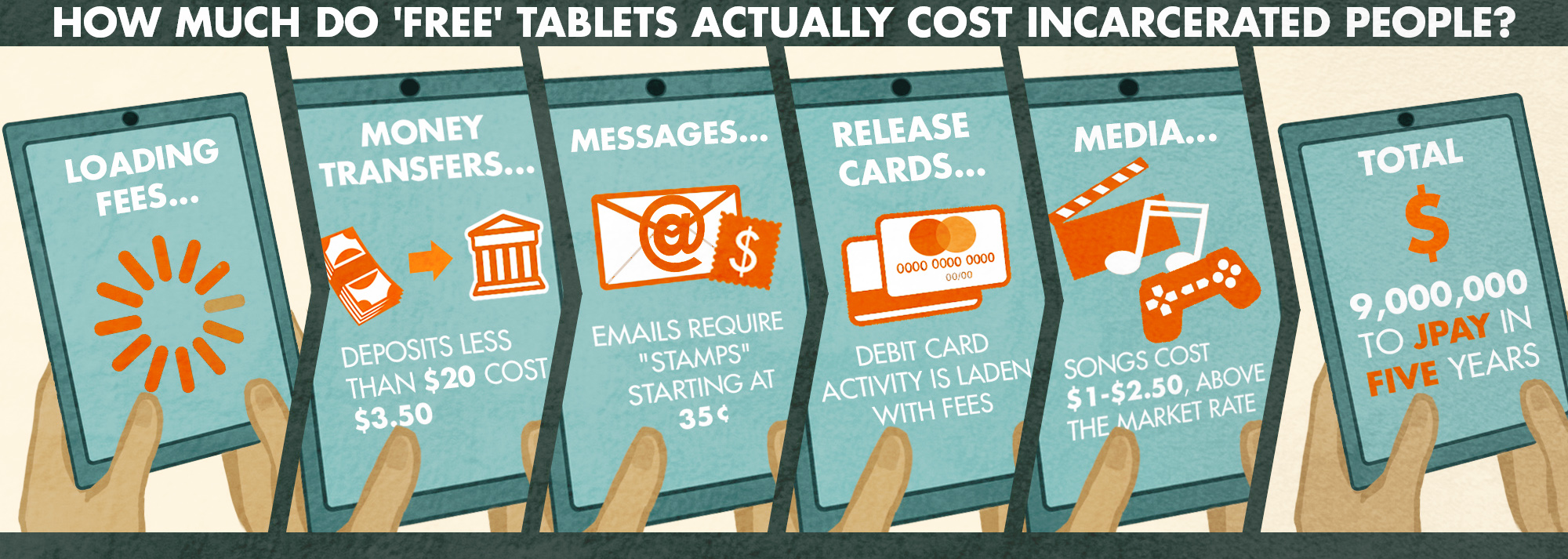

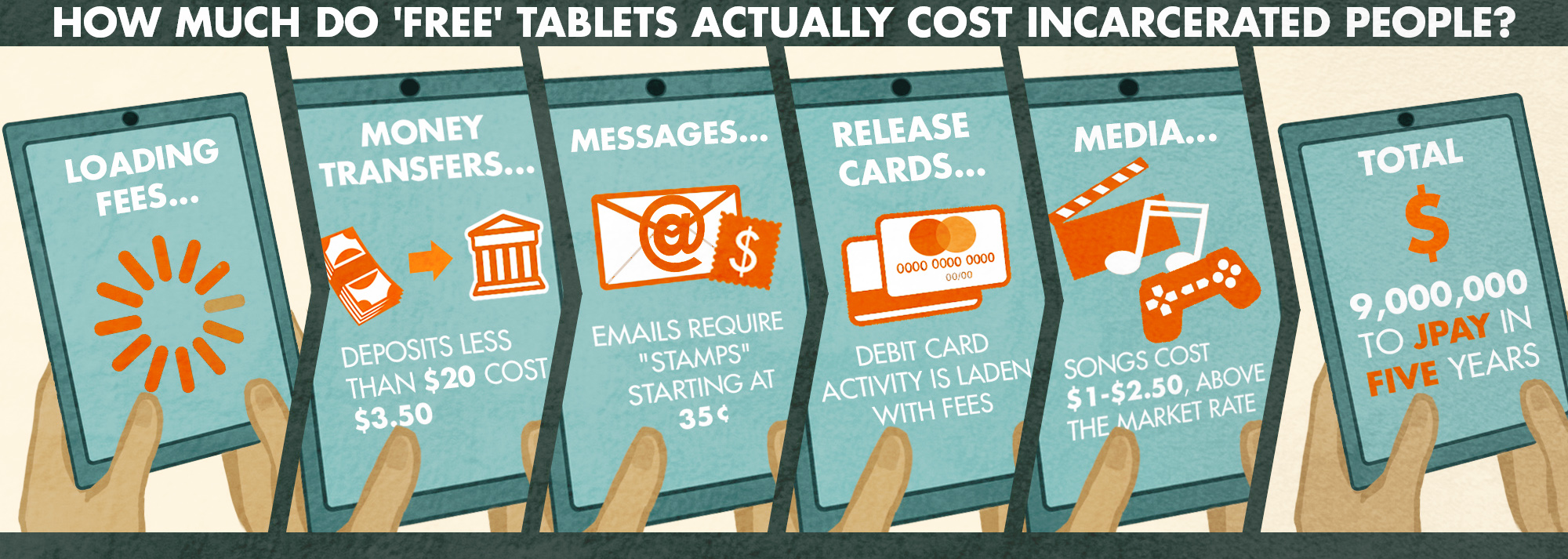

The contract contains virtually every exploitative trick we’ve documented in the past several years, including:

- Taking over the state prisons’ banking system, so they can add fees for services like depositing money. Transferring just $10 to a loved one’s account in a New York state prison will soon cost between $3.15 and $4.15.

- Selling $0.35 “stamps” for a product they have the nerve to call email. (We all have a love/hate relationship with our inboxes, but calling prison messaging email is not fair to email.)

- Providing refunds to incarcerated people when they are released, not in a check, but via a pre-paid debit card rife with fees – such as monthly “service” fees, fees for checking your account balance, or automatic fines for inactivity. (You can request a paper check instead – for $10.)

- Offering video chats at $9 for every 30 minutes.

- Charging above-market prices for media, such as music and e-books.

These provisions explain how JPay expects to make almost $9 million in five years from a contract that is free to the state: by selling profitable, fee-laden services against “complimentary” products like tablets.

New York state legislators never bothered to solve this mystery, but it’s ironic how close some of them got. Take Republican Assemblyman Steve Hawley, who demanded: “If it’s this easy to encourage vendors to provide free tablets to inmates, why aren’t they being provided to our students?” The answer, as columnist Erica Bryant points out, is that students would never purchase a fake “stamp” to send an email to their parents.

Companies like JPay are offering “free” tablet programs to a growing number of states, and legislators should approach these offers with caution. You don’t need an advanced degree to find the hidden costs in New York’s “no-cost” contract. The trick is looking not only at taxpayer costs, but also at the exploitation of incarcerated people and their families.

New York City becomes the first jurisdiction to make calls home from jails free. Who else is going to follow this smart step?

by Peter Wagner,

July 19, 2018

Yesterday, the New York City Council made New York the first jurisdiction in the country to make telephone calls from its prisons and jails free. The city will not only give up the commission it currently makes on phone calls – it is going a step further and making the phone calls themselves free. This change will save the poorest families in the City of New York more than $8 million a year.

In many prisons and jails, calls home from jail are very expensive, costing up to $1/minute. Typically, the facilities grant one phone company a monopoly contract in exchange for the company sharing the revenue with the facility. Some jurisdictions, however, including the New York State prison system, have refused to accept kickbacks on contracts and have instead negotiated for lower rates. They argue (correctly) that giving up that income is a cost-effective investment in lowering recidivism.

Going further and just paying for the calls makes particular sense in jails, where people are either serving short sentences or are detained only because they are too poor to make bail.

This change will be a big deal for the families, but the cost may be quite modest for the system. For example, prison systems like Nebraska have proven that it’s possible to get the rates down to just over a penny a minute when they refuse to take a commission. The New York City jail has economies of scale over Nebraska’s prisons, and the city will be saving the vendor the expensive hassle of individually billing tens of thousands of families.

With this legislation, New York City has not only joined the ethical jurisdictions that are standing up for their poorest families – they have catapulted into the lead. Who will follow?

The legislation takes effect in 270 days, giving the city jail system time to negotiate a new telephone contract.

We argue that Securus' history of misconduct should make it ineligible to acquire competitor ICSolutions.

by Aleks Kajstura,

July 17, 2018

Yesterday, the Prison Policy Initiative joined the Wright Petitioners and other advocates in calling on the Federal Communications Commission to stop the merger of prison phone companies Securus and ICSolutions. If the FCC approves Securus’ acquisition of ICSolutions, it will effectively hand the market for prison phone services to Securus and its last major competitor, GTL. Our filing objects to the merger under the FCC’s “character and fitness” test.

Securus’ history of repeatedly flouting commission rules – including deliberately misleading the FCC during a similar review last year, for which it was punished with an unprecedented $1.7 million fine – should alone make it ineligible to purchase one of its competitors. The company has repeatedly tried to circumvent regulation in order to increase its profits from prison phone calls, and as recently as May was caught enabling illegal cell phone tracking.

Our filing includes a detailed analysis of the concentration of the prison and jail telephone industry. We calculated market share in two different ways; by either measure, Securus and GTL are poised to control between 74% and 83% of the market. Except for ICSolutions — which Securus is seeking to acquire – no other company has above 3% market share.

This diminished competition will give facilities less choice and less ability to draft contracts that truly meet their needs. Such a decline in the power of facilities to negotiate with the phones companies comes at a particularly bad time: when a growing number of facilities are finally seeking contracts that lower phone rates for the families of incarcerated people.

Securus and ICSolutions have until July 23rd to respond to our objections. The Federal Communications Commission will rule shortly thereafter, either allowing the license transfer to go ahead, rejecting it, or ordering a hearing.

Formerly incarcerated people overwhelmingly want to work, but they face huge obstacles in the job market.

July 10, 2018

Easthampton, Mass. – For the 5 million formerly incarcerated people living in the U.S., landing a job means more than just personal success: It means finding a place in their communities and being able to care for their loved ones again.

It’s well known that the obstacles to finding a job are severe for formerly incarcerated people. The scale of this problem, however, has been difficult to measure – until now.

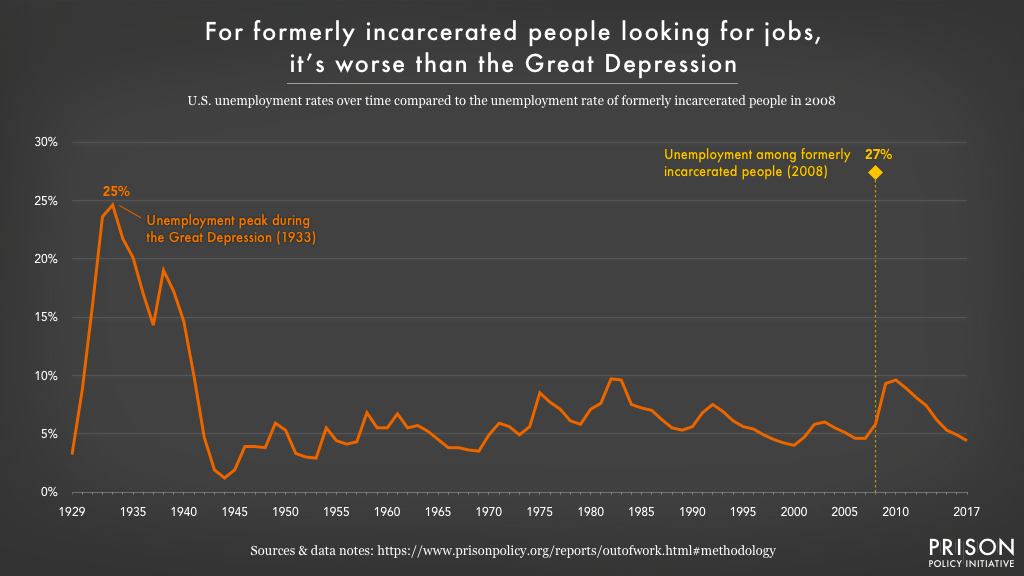

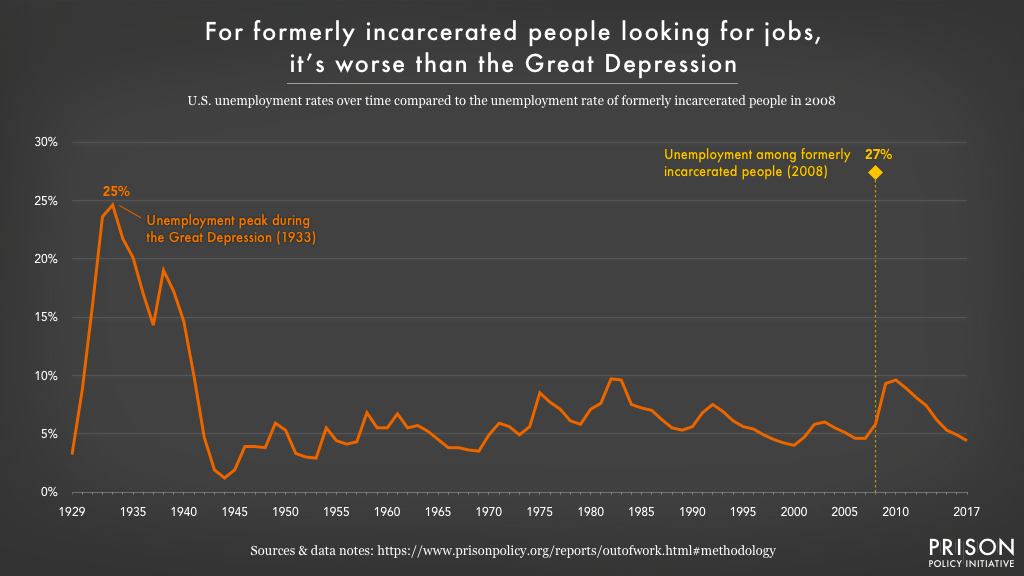

In Out of Prison & Out of Work, the Prison Policy Initiative calculates that 27% of formerly incarcerated people are looking for a job but can’t find one:

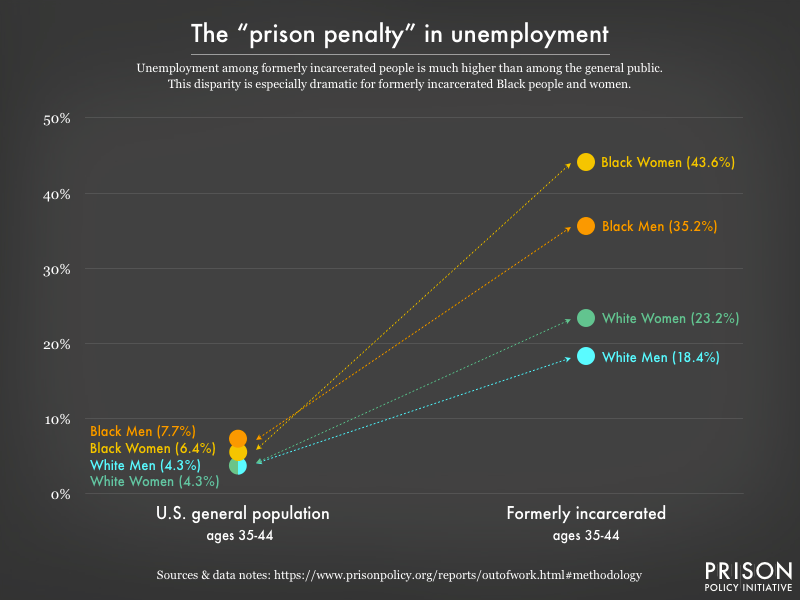

This rate, which surpasses anything Americans have experienced since the height of the Great Depression, is especially striking given the report’s other findings:

- Formerly incarcerated people are more likely than the average American to want to work;

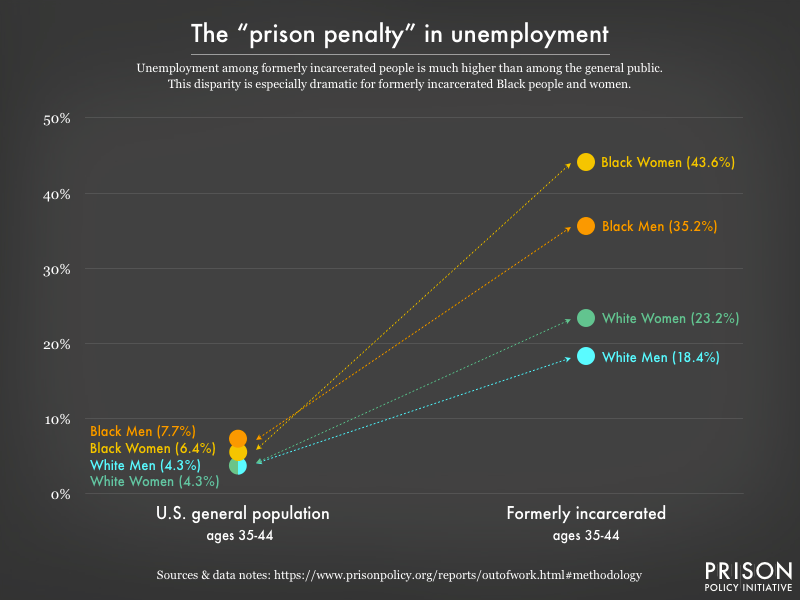

- People of color and women face the worst “penalties” in the job market after going to prison, making historical inequalities in the labor force even worse;

- Unemployment is highest for people released in the last two years, when they are most vulnerable to re-incarceration.

“These high unemployment rates reflect public will, policy, and practice – not differences in aspirations,” said author Lucius Couloute. In the report, he lays out policy solutions for closing this vast employment gap, including:

- A temporary basic income for formerly incarcerated people after their release;

- Automatic mechanisms for criminal record expungement;

- Occupational licensing reform at the state and industry levels.

Today’s report is the first of three to be released by the Prison Policy Initiative this summer, focusing on the struggles of formerly incarcerated people to access jobs, housing, and education. Utilizing data from a little-known and little-used government survey, Couloute and other analysts can describe these problems with unprecedented clarity. In this report and the two more to follow, they recommend reforms to ensure that formerly incarcerated people – already punished by a harsh justice system – are no longer punished for life by an unforgiving economy.