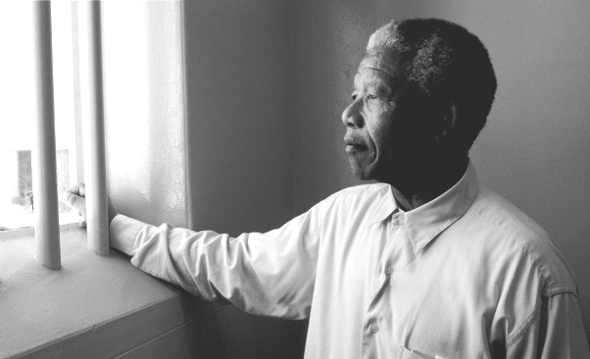

Johnny Cash consistently identified with the downtrodden and recorded a number of songs about the hopeless misery of imprisonment.

by Peter Wagner,

September 12, 2003

San Quentin, may you rot and burn in hell.

May your walls fall and may I live to tell.

May all the world forget you ever stood.

And the whole world will regret you did no good.

–Johnny Cash, “San Quentin” 1969

In Memory of Johnny Cash

February 26, 1932 – September 12, 2003

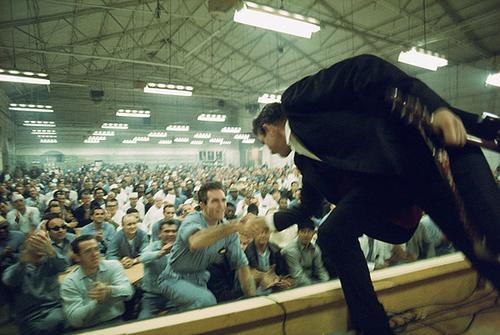

September 12, 2003 — The Man in Black, country music star Johnny Cash, died today at age 71. Although Johnny only spent one day in jail himself, he consistently identified with the downtrodden, eagerly performing a number of free concerts for prisoners. Two of these concerts became popular albums Live at San Quentin and Live at Folsom Prison. He was best known for Folsom Prison Blues, about the endless loneliness faced by a reformed man in prison:

I hear the train a-comin’

It’s rollin’ round the bend.

And I ain’t seen the sunshine

Since I don’t know when.

I’m stuck in Folsom Prison

And time keeps draggin’ on.

Johnny wrote or recorded a number of songs about the hopeless misery of imprisonment including Send a picture of Mother, The Wall, The walls of a prison, There ain’t no good chain gang, I got stripes, (I heard that) lonesome whistle, Green, Green Grass of Home, Give my love to Rose, Jacob Green, Austin Prison, Orleans Parish Prison, and a number of songs authored by prisoners present at his performances, including I don’t know where I’m bound.

In memory of the Man in Black, his work, and his music, it seemed appropriate to highlight two of his lesser known songs: “Man in Black” and “San Quentin”.

We’ll miss you Johnny. May all the world never forget you sang. All the world will rejoice you did so much good.

Man In Black

Well, you wonder why I always dress in black,

Why you never see bright colors on my back,

And why does my appearance seem to have a somber tone.

Well, there’s a reason for the things that I have on.

I wear the black for the poor and the beaten down,

Livin’ in the hopeless, hungry side of town,

I wear it for the prisoner who has long paid for his crime,

But is there because he’s a victim of the times.

I wear the black for those who never read,

Or listened to the words that Jesus said,

About the road to happiness through love and charity,

Why, you’d think He’s talking straight to you and me.

Well, we’re doin’ mighty fine, I do suppose,

In our streak of lightnin’ cars and fancy clothes,

But just so we’re reminded of the ones who are held back,

Up front there ought ‘a be a Man In Black.

I wear it for the sick and lonely old,

For the reckless ones whose bad trip left them cold,

I wear the black in mournin’ for the lives that could have been,

Each week we lose a hundred fine young men.

And, I wear it for the thousands who have died,

Believen’ that the Lord was on their side,

I wear it for another hundred thousand who have died,

Believen’ that we all were on their side.

Well, there’s things that never will be right I know,

And things need changin’ everywhere you go,

But ’til we start to make a move to make a few things right,

You’ll never see me wear a suit of white.

Ah, I’d love to wear a rainbow every day,

And tell the world that everything’s OK,

But I’ll try to carry off a little darkness on my back,

‘Till things are brighter, I’m the Man In Black

San Quentin

An’ I was thinkin’ about you guys yesterday. Now, I been here three times before, an’ I think I understand a little bit about how you think about some things, it’s none of my business how you feel about some other things and I don’t give a damn how you feel about some other things! But anyway, I tried to put myself in your place, and I believe this is the way that I would feel about San Quentin.

San Quentin, you’ve been livin’ hell to me.

You’ve galled at me since nineteen sixty three.

I’ve seen ’em come and go and I’ve seen them die,

And long ago I stopped askin’ why.

San Quentin, I hate ev’ry inch of you.

You’ve cut me and you’ve scarred me through an’ through.

And I’ll walk out a wiser, weaker man;

Mr Congressman, why can’t you understand?

San Quentin, what good do you think you do?

Do you think that I’ll be different when you’re through?

You bend my heart and mind and you warp my soul,

Your stone walls turn my blood a little cold.

San Quentin, may you rot and burn in hell.

May your walls fall and may I live to tell.

May all the world forget you ever stood.

And the whole world will regret you did no good.

San Quentin, you’ve been livin’ hell to me.

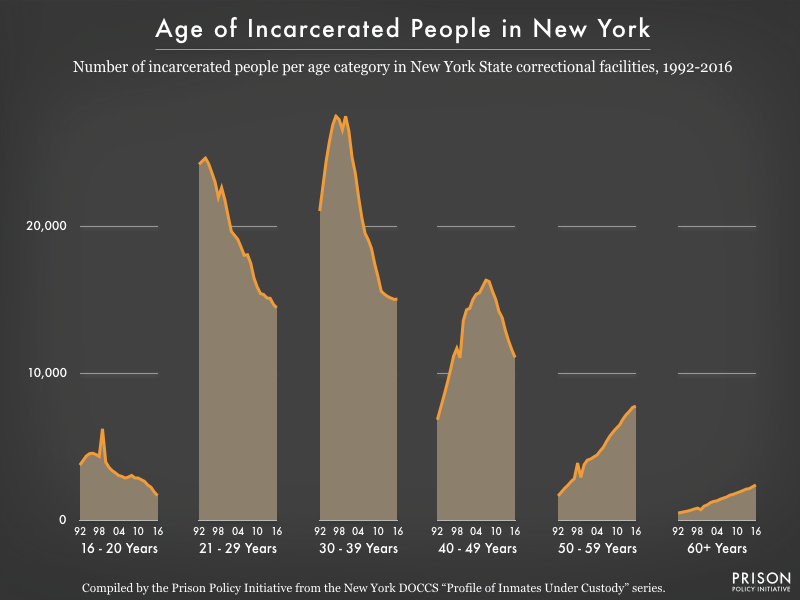

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.