2017 was another big year for powerful data visualizations from the Prison Policy Initiative. These are our 9 favorites.

by Peter Wagner,

December 29, 2017

2017 was another big year for powerful data visualizations from the Prison Policy Initiative. These are 9 of our favorites:

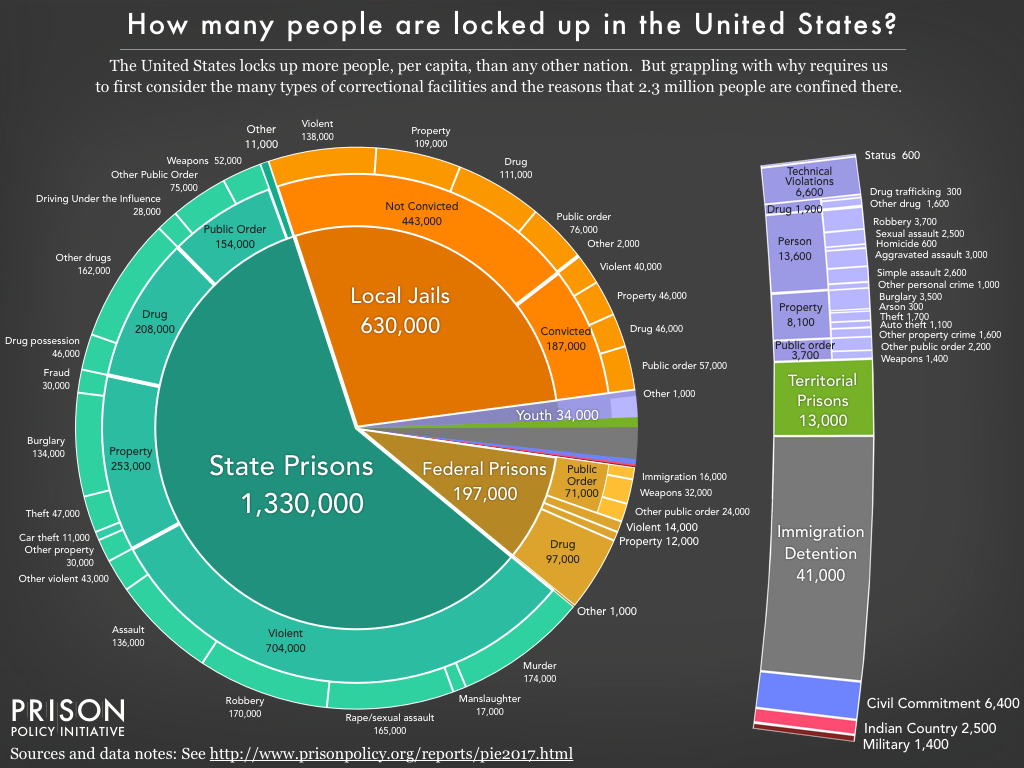

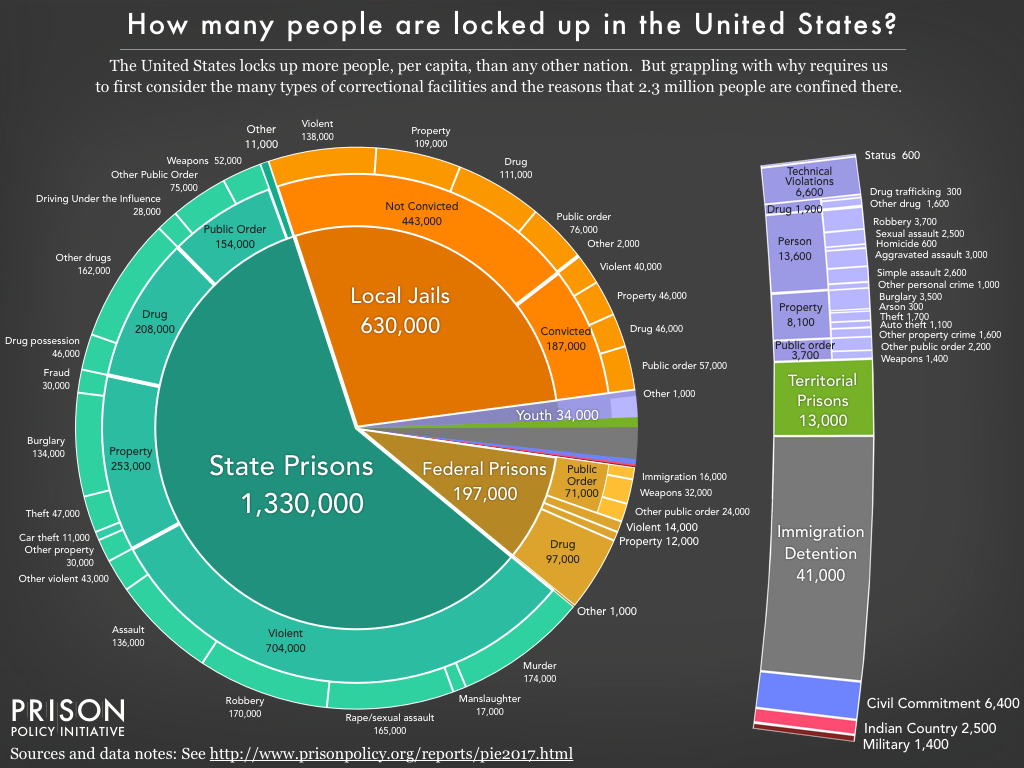

1. The “whole pie”

We updated our most famous data visualization for 2017, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie:

This report also included four slideshows of additional detail on different parts of the carceral system — including the under-discussed world of jails — and some state-to-state comparisons.

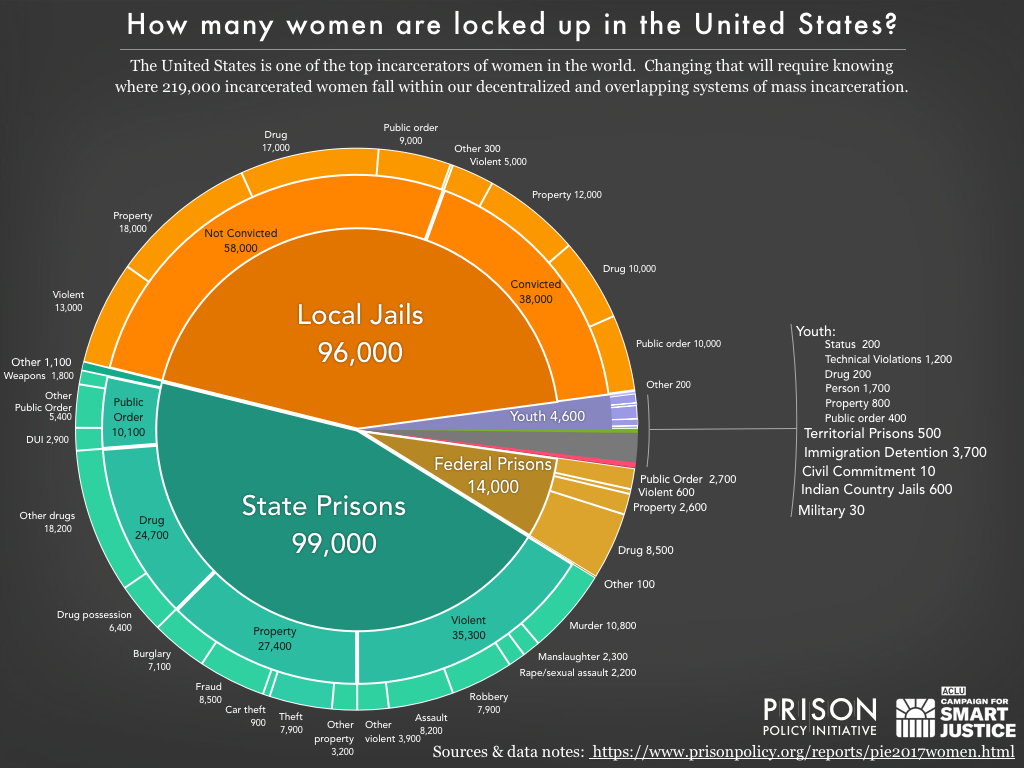

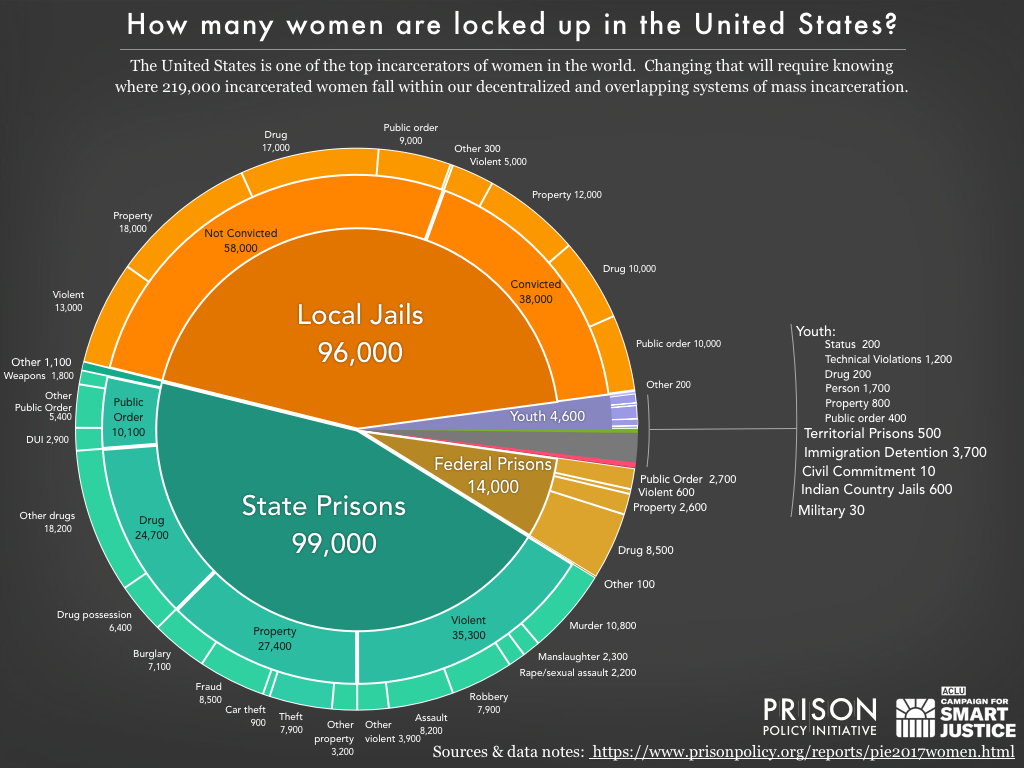

2. The “whole pie” of women’s incarceration

In partnership with the ACLU, we produced Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie to aggregate the disparate systems of confinement and illustrates where and why 219,000 women are locked up in the U.S.:

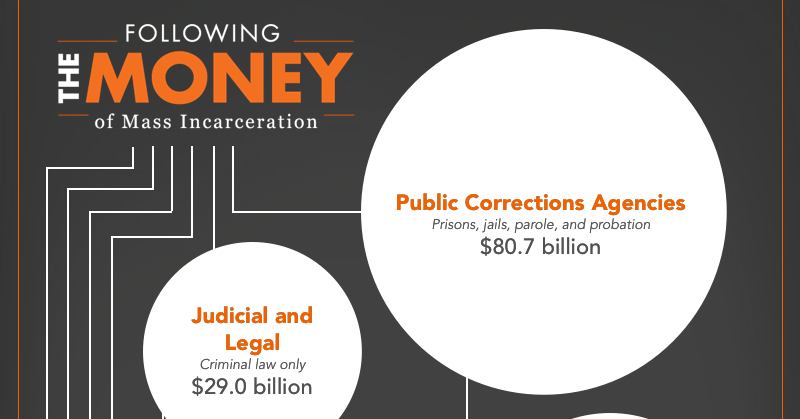

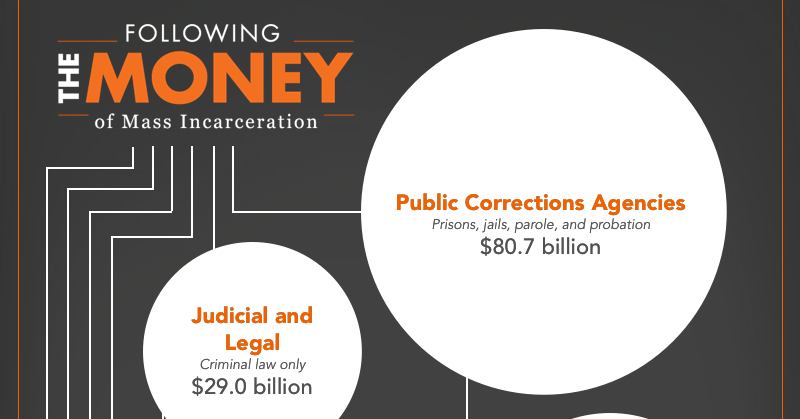

3. Following the money of mass incarceration

In the first-of-its-kind report accompanying this graphic, we find that the system of mass incarceration costs the government and families of justice-involved people at least $182 billion every year. In this report and visualization, we follow the money:

Please click to see the full visualization.

Please click to see the full visualization.

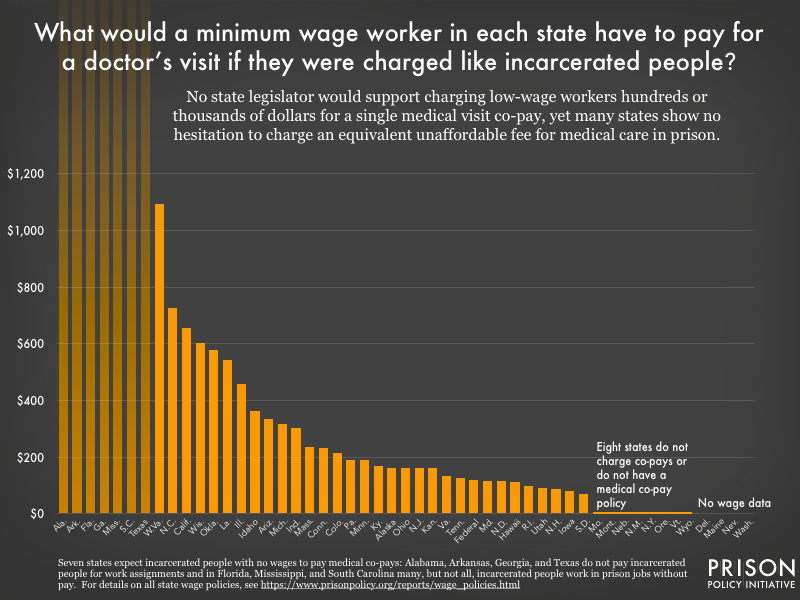

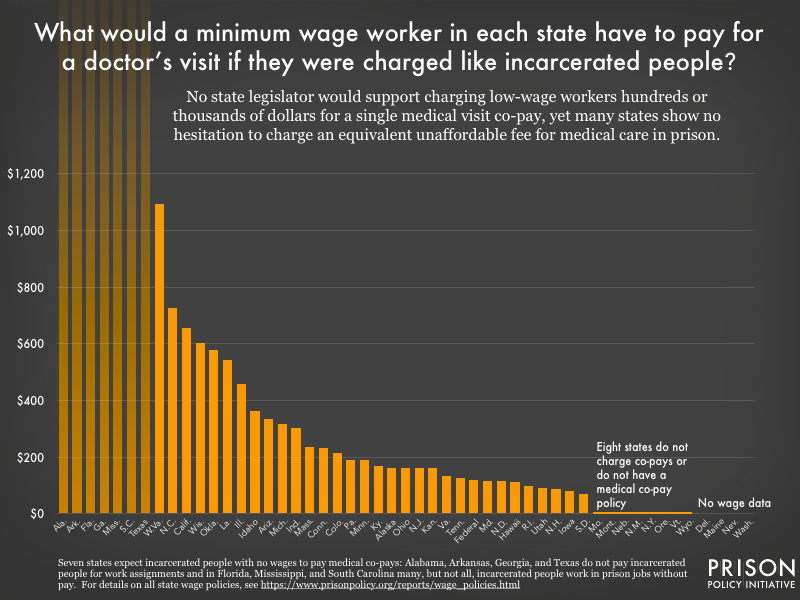

4. The short-sighted cruelty of charging incarcerated people high fees for their own medical care

If your doctor charged a $500 co-pay for every visit, how bad would your health have to get before you made an appointment? You would be right to think such a high cost exploitative, and your neighbors would be right to fear that it would discourage you from getting the care you need for preventable problems. In a 50-state analysis of medical co-pays in prison, we find that this is the hidden reality of prison life:

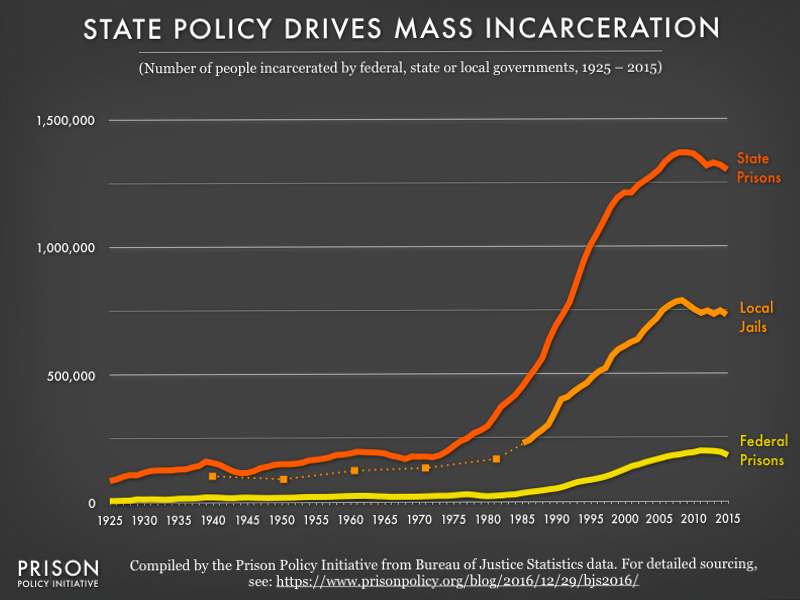

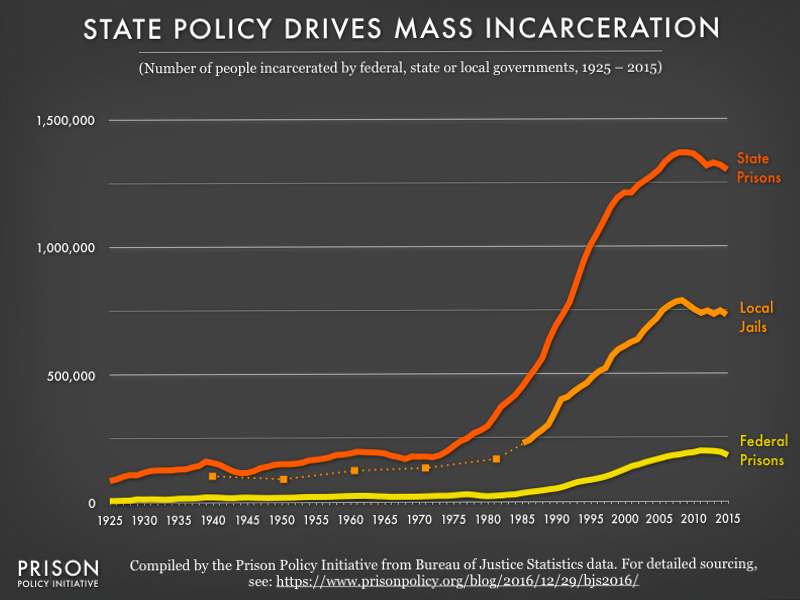

5. Putting the emphasis of criminal justice reform where it belongs: on state and local policies

The federal government gets all the attention, but the real story of mass incarceration is at the state and local levels. We’ve been continuing to update this key visual:

For more on this perspective, see our blog post President Obama’s parting reminders on criminal justice reform.

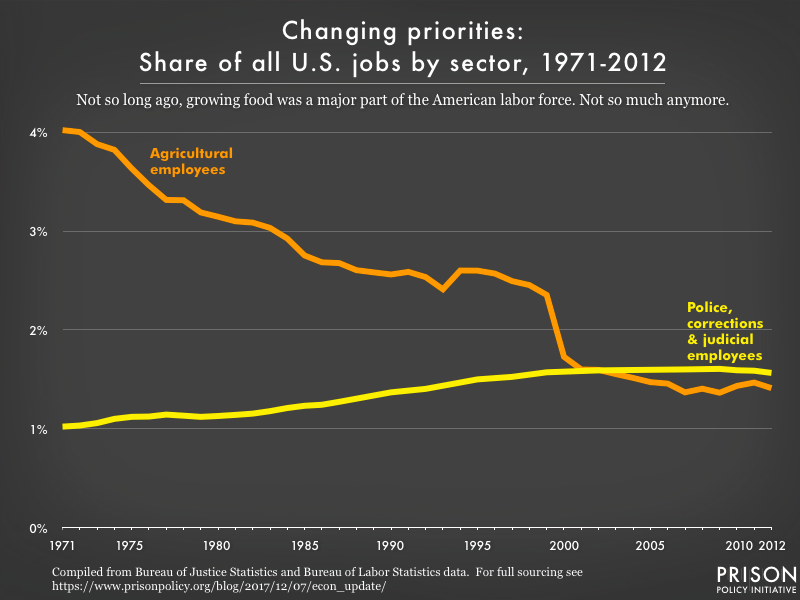

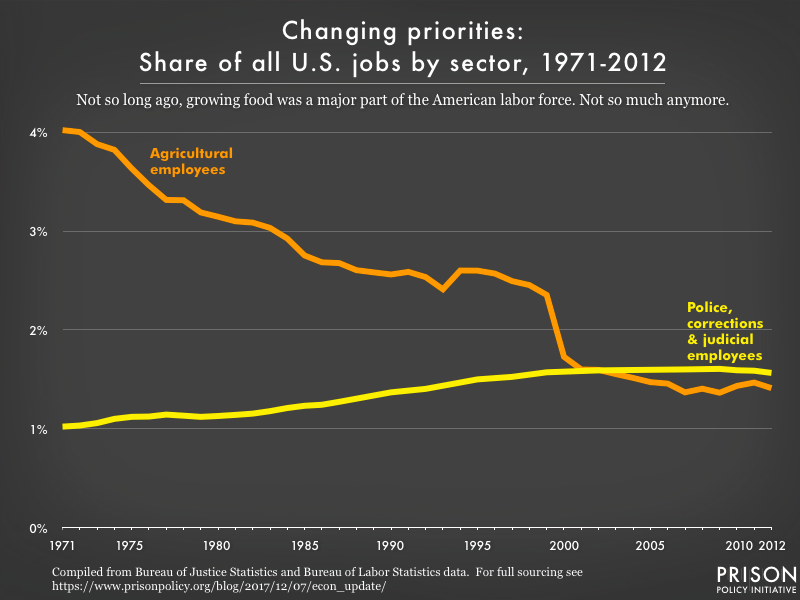

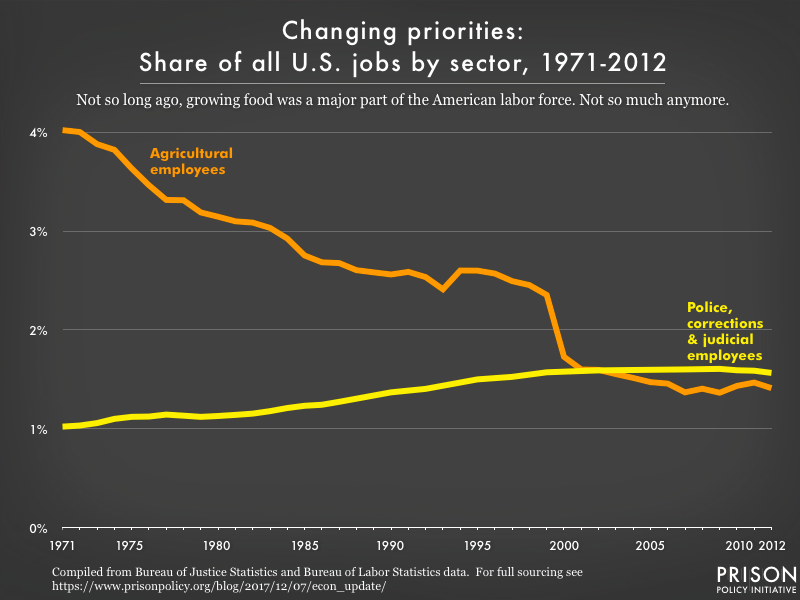

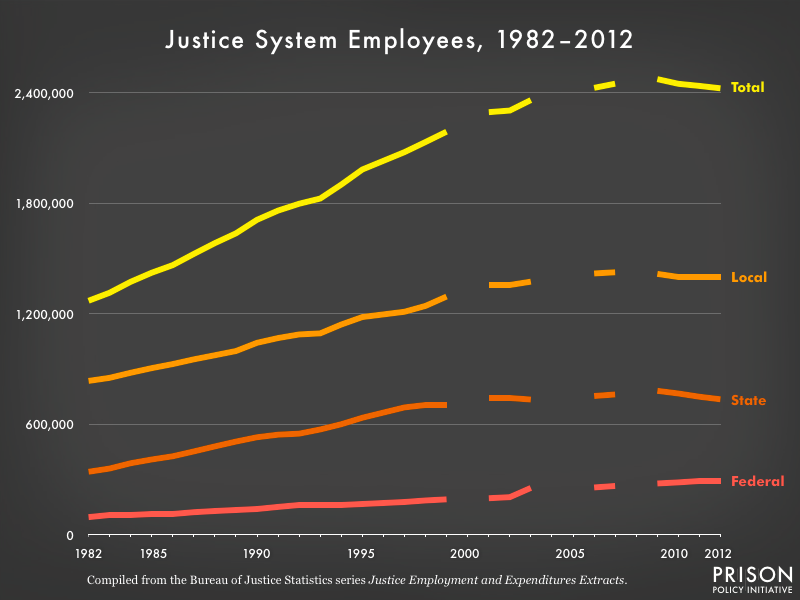

6. Tracking this country’s priorities

For a blog post Tracking the impact of the prison system on the economy, we highlighted one key and unfortunate shift in our nation’s economic priorities:

The 2.3 million incarcerated people in the United States are, of course, excluded from the labor force and therefore are not reflected in analyses of labor force participation. Including them would make the portion of the workforce that is involved in the mass incarceration system even larger.

The 2.3 million incarcerated people in the United States are, of course, excluded from the labor force and therefore are not reflected in analyses of labor force participation. Including them would make the portion of the workforce that is involved in the mass incarceration system even larger.

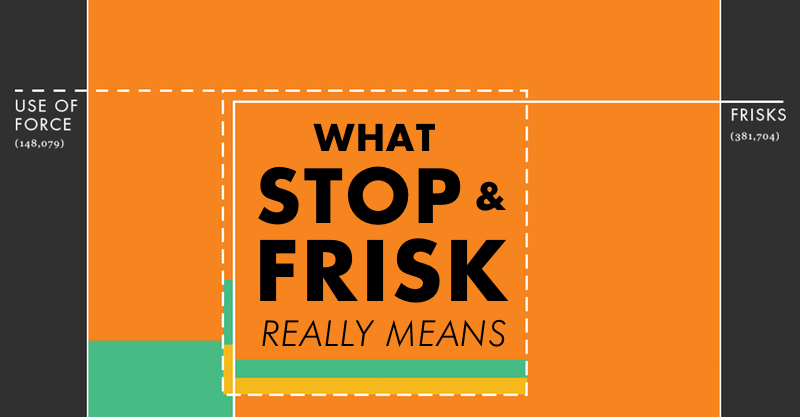

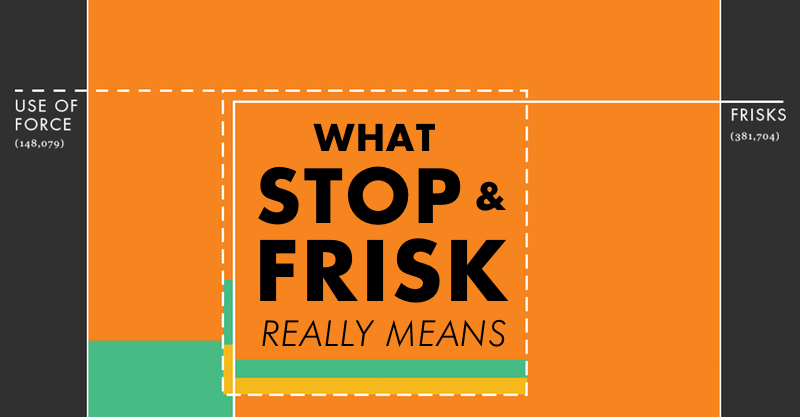

7. Racial discrimination and use of force in “stop and frisk” policing

President Trump supports “stop and frisk” policing; but a return to the violent police tactic would be – to use some of the president’s favorite Twitter words – “a disaster!” In this visualization and report (you’ll need to click through to get the full effect) we explore the ineffectiveness of the police tactic and the racial disparities in who is stopped, who is frisked and who has force used against them by the police:

Please click to see the full visualization in its original context.

Please click to see the full visualization in its original context.

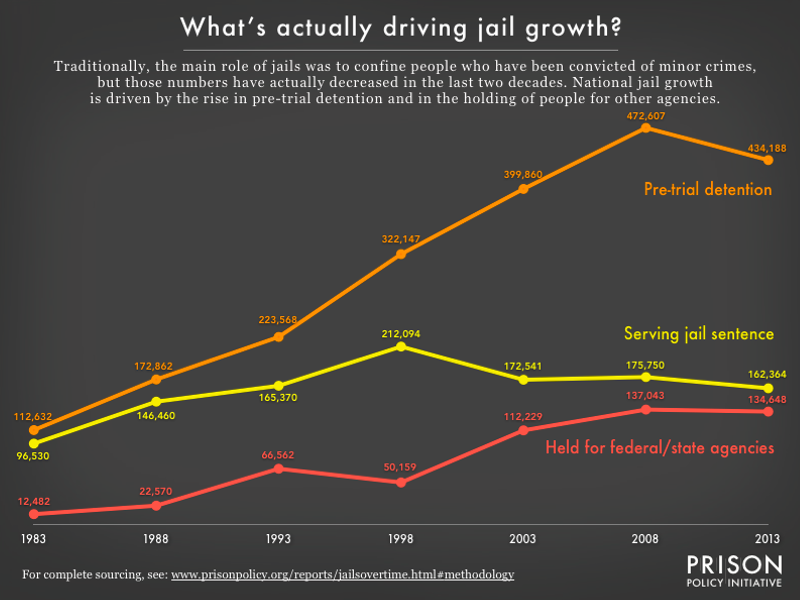

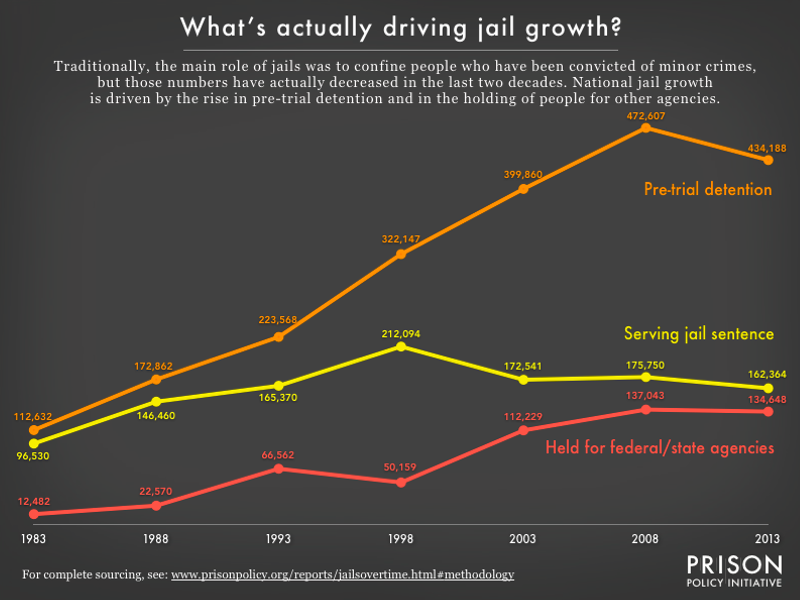

8. Exploring the causes of jail growth

For our report Era of Mass Expansion: Why State Officials Should Fight Jail Growth we started with the big picture view of the two reasons why jail populations are growing:

Figure 1. Most state policymakers are not tracking jails in the first place, and the jails’ frequent practice of renting cells to other agencies makes it difficult to draw conclusions from the little data that is available. This report offers a new analysis of federal data to offer a state-by-state view of how jails are being used and we find that, even more than previous research has implied, pre-trial populations are driving “traditional jail” growth. The data behind this graph is in Table 1.

Figure 1. Most state policymakers are not tracking jails in the first place, and the jails’ frequent practice of renting cells to other agencies makes it difficult to draw conclusions from the little data that is available. This report offers a new analysis of federal data to offer a state-by-state view of how jails are being used and we find that, even more than previous research has implied, pre-trial populations are driving “traditional jail” growth. The data behind this graph is in Table 1.

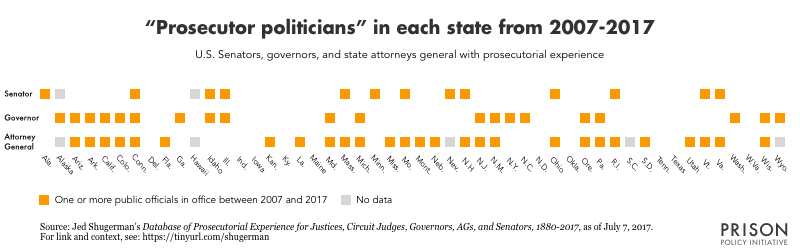

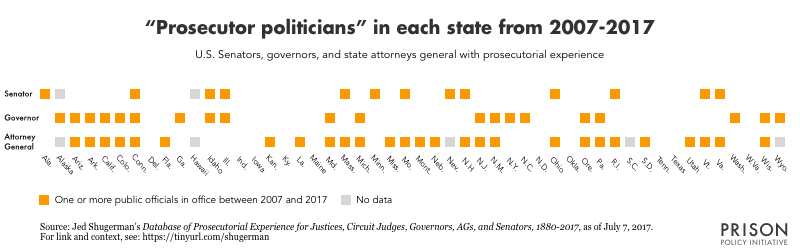

9. The rise of the “prosecutor politician”

Fordham University historian Jed Shugerman has finally made it possible to examine the scale of prosecutors’ influence on American politics and justice throughout history. At great effort, he produced the data and made it available to the public. To draw more attention to it, we made a visualization to accompany our blog post about the data:

In at least 38 states, a senator, governor, and/or attorney general holding office in the past 10 years was once a prosecutor. This chart may understate the prevalence of these “prosecutor politicians,” since the source is a work in progress and has no data for some positions in five states as of July 7, 2017, and does not include changes in all offices after January 2017.

In at least 38 states, a senator, governor, and/or attorney general holding office in the past 10 years was once a prosecutor. This chart may understate the prevalence of these “prosecutor politicians,” since the source is a work in progress and has no data for some positions in five states as of July 7, 2017, and does not include changes in all offices after January 2017.

Journalists who use our research in new, creative ways play a crucial role in engaging the public with criminal justice issues. These are some of our favorite stories of 2017 that feature our work.

by Wendy Sawyer,

December 28, 2017

One of our goals here at the Prison Policy Initiative is to engage the public in current criminal justice issues. Journalists who use our research in new, creative ways play a crucial role in that process. These are some of our favorite stories of 2017 that feature our work, starting with the most recent:

-

The end of American prison visits: jails end face-to-face contact – and families suffer

The end of American prison visits: jails end face-to-face contact – and families suffer

Shannon Sims

The Guardian

December 9, 2017

For three years, we’ve been tracking the quiet spread of virtual jail “visits” in jails across the country; fortunately, a surge of hard-hitting journalism is pushing back, building off of our research and exposing the harms of eliminating family visits in favor of video calls. In Shannon Sims’ deep dive into the video calling industry for The Guardian, she investigates the switch from in-person family visits to expensive video calls in one jail outside of downtown New Orleans. The Guardian’s article raises another important point that we haven’t raised in our own work or seen raised elsewhere: does international human rights law require jails to allow in-person visitation? According to Sims, this is one more reason that using video calling as a replacement for real visits is bad policy.

NBA Pistons Owner Under Fire for Deal on Inmate Phone Service

NBA Pistons Owner Under Fire for Deal on Inmate Phone Service

Todd Shields

Bloomberg

July 24, 2017

When the sale of prison and jail telecom giant Securus Technologies to Platinum Equity was announced in May, we joined with other advocates to ask the FCC to block the sale and investigate the company’s ongoing defiance of FCC regulations. We also questioned why Platinum’s owner Tom Gores – who has built a reputation for helping recovery efforts in Detroit and Flint – would invest in a company that charges Michigan residents as much as $8.20 for a single minute of a call from an incarcerated loved one. Bloomberg picked up the story and ran with it, in the process producing a comprehensive review of the biggest news related to the prison and jail phone industry in the past year.-

What’s actually driving local jail growth?

What’s actually driving local jail growth?

Mark Bennett

Tribune-Star

June 4, 2017

Vigo County, Indiana, like many counties around the country, has plans to build a new, larger jail to accommodate its growing jail population. Indiana reporter Mark Bennett uses our report Era of Mass Expansion to explore the underlying causes of jail growth in the state, like its high rate of pretrial detention and the fact that 14% of its jail beds are held for outside authorities. Bennett’s reporting gives local and state authorities plenty of reasons to reconsider jail expansion.

-

The plunder of the American prison system

The plunder of the American prison system

Ryan Cooper

The Week

January 25, 2017

Ryan Cooper elegantly summarizes our Following the Money of Mass Incarceration report, with all its data intricacies, and pulls out the most salient threads for discussion. Going further, he connects the massive growth and abuses of the criminal justice system to the political economy of incarceration, concluding “the profit motive… tends to dissolve moral considerations.”

-

Driver’s Licenses, Caught in the War on Drugs

Driver’s Licenses, Caught in the War on Drugs

The Editorial Board

The New York Times

January 3, 2017

The New York Times Editorial Board responds to our December 2016 report, Reinstating Common Sense, unequivocally denouncing laws that automatically suspend driver’s licenses for drug offenses unrelated to driving and then charge costly reinstatement fees: “These laws… are simply cruel and stupid, and it is past time to expunge them from the books.” Strong editorial support like this fuels our advocacy work and the work of advocates in the remaining states that have yet to eliminate these outdated and counterproductive laws.

Useful and under-exposed research from 2017 that contributed to our movement's understanding of key issues in criminal justice.

by Lucius Couloute and Wanda Bertram,

December 28, 2017

It’s been an important year for criminal justice research (you can visit our Research Clearinghouse for the most up-to-date work). And at the end of each year, we like to call attention to some of the most useful or under-exposed research contributing to our movement’s understanding of key issues in criminal justice. Here’s our list for 2017:

-

The Downstream Consequences of Misdemeanor Pretrial Detention

Paul Heaton, Sandra Mayson & Megan Stevenson

Stanford Law Review

March 2017

In this rigorous study, the authors find disturbing effects of pre-trial detention on both case outcomes and public safety. Detained misdemeanor defendants were more likely than similarly-situated releasees to plead guilty, more likely to be sentenced to jail, and they received longer jail sentences. Pretrial detention was also related to more future crime, contradicting the common bail-industry defense of money bail as a means of protecting communities. The importance of this study, detailed on our blog, can’t be overstated: it demonstrates that money bail actually increases risks to public safety, influences case outcomes in ways that contribute to more incarceration, and infringes on constitutional rights.

-

Out of Sight: The Growth of Jails in Rural America

Vera Institute of Justice

June 2017

630,000 people are incarcerated in local jails across the country. Over the course of the last decade, though, the use of jails has declined in cities and grown in rural areas. In Out of Sight Vera Institute of Justice uses its Incarceration Trends data tool to detail this shift, shining a light on the changing landscape of mass incarceration.

-

Language from police body camera footage shows racial disparities in officer respect.

Rob Voigta, Nicholas P. Camp, Vinodkumar Prabhakaran, William L. Hamilton, Rebecca C. Hetey, Camilla M. Griffiths, David Jurgens, Dan Jurafsky, and Jennifer L. Eberhardt

June 2017

New research out of Stanford University substantiates what Black America has always known – that police officers treat Blacks differently than they do whites. See the original report and our blog post about it.

-

Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood

Rebecca Epstein, Jamilia J. Blake, and Thalia González

Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality

June 2017

This important report expands previous research about bias against Black boys to find that adults view Black girls as less innocent and more adult-like than their white peers, especially in the age range of 5-14. Although under-explored, the “adultification” of Black girls has ramifications for both educational and justice system outcomes.

-

The Rise of the “Prosecutor Politician”: Database of Prosecutorial Experience for Justices, Circuit Judges, Governors, AGs, and Senators, 1880-2017

Jed Shugerman

July 2017

Thanks to his groundbreaking new dataset, Fordham University historian Jed Shugerman has finally made it possible to examine the scale of prosecutors’ influence on American politics and justice throughout history. See the data, Jed Shugerman’s announcement, and our blog post and data visualization of Shugerman’s data.

- A Matter of Time: The Causes and Consequences of Rising Time Served in America’s Prisons

The Urban Institute

July 2017

States are rightly applauded for reducing sentences and expanding alternatives to prison for low-level offenders, but these reforms “won’t be enough” to end mass incarceration, says a July feature from the Urban Institute. For those not familiar with how sentencing for violent offenders has driven prison growth since the 1980s, this report presents perhaps the clearest and most accessible explanation to date. Visuals show how both the length of the longest prison terms and the number of people serving such terms have grown in 44 states (that is, every state for which data is available). The report urges state policymakers to wrestle with hard questions: “How long is too long? What is long enough? And do longer prison terms really translate into justice, rehabilitation, and public safety?”

-

Who Does Civil Asset Forfeiture Target Most?

Nevada Policy Research Institute

July 2017

The short answer from this important study of civil asset forfeiture is that the practice targets poor people. Civil asset forfeiture is the controversial practice of allowing the police to seize property on the belief that the owner was involved in criminal activity. The police are not required to charge the owner with a crime, and the owner has to sue to get their property returned, so the police have an economic incentive to seize smaller sums from the poor rather than larger sums from people who could sue to get their property back.

-

The Geography of Incarceration in a Gateway City:

The Cost and Consequences of High Incarceration Rate Neighborhoods in Worcester

MassInc

September 2017

In an innovative report, MassInc reveals how incarceration is concentrated in particular Worcester Massachusetts neighborhoods. And in eight neighborhoods, over a million dollars per year is spent on incarcerating community members. MassInc also did a similar and even deeper report in 2016 about where incarcerated people are concentrated in Boston.

-

The Growth, Scope, And Spatial Distribution Of People With Felony Records in the United States, 1948 To 2010

Sarah K.S. Shannon, Christopher Uggen, Jason Schnittker, Melissa Thompson, Sara Wakefield, Michael Massoglia

September 2017

Between 70 and 100 million people are estimated to have some kind of criminal record, but until now it’s been difficult to construct a current estimate of the number of people with felony convictions. New research from Sarah K. S. Shannon and colleagues fills that gap by providing historical and state-level estimates of the number of people with felony records (19 million in total), allowing researchers and policymakers to better understand the expansion of harsh criminalization across time, space, and racial groups. Along with the article, the authors have also provided appendices which include state-level tables by decade, useful for future research on mass criminalization.

- Immigration Population Since the 1990s

CrImmigration Blog

September 2017

The Department of Homeland Security holds tens of thousands of immigrants in civil detention centers every year, the exact number of which is not too difficult to come by (thanks in part to a DHS mandate that a minimum number of detention beds be full at all times). But how many immigrants are held in criminal facilities, such as federal prisons, and how much has this number grown? These data are much trickier to measure, but CrImmigration author César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández took up the challenge in September and found that immigrants in federal prisons have increased more than sevenfold in 25 years.

- Punishment Is Not a “Service”: The injustice of pretrial conditions in Cook County

Chicago Community Bond Fund

October 2017

By posting bail for poor defendants, the Chicago Community Bond Fund helps people avoid the harms of pretrial confinement, but their October report details how the pretrial system can ruin defendants’ lives even after they have posted bail. Under the pretext of “helping” defendants make their court dates, judges frequently subject them to electronic monitoring, mandatory check-ins, tight curfews and drug testing, intimidating defendants and setting them up to fail. CCBF profiles several of its own clients to make the case that restrictive pretrial requirements, far from being “services,” are “contributing to the criminalization of vulnerable communities” and “compounding racial inequity in the criminal legal system.”

In 2017, the Prison Policy Initiative's campaigns saw real progress resulting in important policy changes, and our research brought to light issues that will demand more attention in the year ahead.

by Wendy Sawyer,

December 28, 2017

At a time when the White House is setting back many of our goals, it’s important to reflect on our victories in the movement for criminal justice reform. And there were important victories in 2017: this year, the Prison Policy Initiative’s campaigns saw real progress resulting in important policy changes, and our research brought to light issues that will demand more attention in the year ahead.

Here are some of the biggest wins in our campaigns this year:

- In the wake of our December 2016 report Reinstating Common Sense: How driver’s license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving are falling out of favor, which received editorial support from The New York Times, lawmakers around the country took action. Mississippi, Florida, and Texas legislators introduced bills to reject the federal law that automatically suspends licenses for drug offenses unrelated to driving. The D.C. Council passed legislation repealing the law that automatically revokes or suspends the driver’s licenses of drug offenders. And the Virginia legislature passed a compromise law that exempted first-time marijuana offenders from automatic suspensions.

- At the national level, Rep. Beto O’Rourke (D-TX) introduced a bipartisan bill to repeal the federal transportation law requiring states to suspend driver’s licenses for drug offenses.

- In two major victories, California and Illinois passed legislation protecting traditional in-person visitation this year. Illinois’s law further mandates that video calling systems be provided at the “lowest possible cost” and prohibits authorities from profiting from these calls. New Jersey is currently considering a bill that would provide even more protections: capping video call costs, banning commissions, and banning fees for professional visits from lawyers and clergy. And Massachusetts’ House and Senate recently each passed criminal justice reform bills with amendments that would protect in-person visitation. The bills are now being reconciled before a final version eventually heads to the Governor’s desk.

- In July, Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D-IL) introduced the Video Visitation and Inmate Calling in Prisons Act of 2017, which would require the FCC to regulate the use of video visitation and inmate calling services in correctional facilities, protecting in-person visitation and regulating the high costs of calling services.

- For the first time, the New Jersey legislature passed a bill to end prison gerrymandering. Although it was ultimately vetoed by Gov. Christie, New Jersey is now poised to end prison gerrymandering under the new governor.

This year, we also published groundbreaking research calling attention to local jails, the political power of sheriffs, women’s incarceration, racial disparities in police use of force, the high cost of medical co-pays in prison, exploitative prison and jail services for phones, tablets, and money transfers, and much more. Our most notable reports include:

- Following the Money of Mass Incarceration

In a first-of-its-kind report, we aggregate economic data to offer a big picture view of who pays for – and who benefits from – mass incarceration. We find that our system of mass incarceration costs the government and families of justice-involved people at least $182 billion every year. By identifying some of the stakeholders and quantifying their “stake” in maintaining the status quo, our data visualization shows how entrenched mass incarceration has become in our economy.

- Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2017

We updated the most popular visual in the criminal justice reform movement to include 15 new data visuals, providing policymakers and the public a clear and accurate big-picture view of punishment in the U.S. While the White House attempts to move away from criminal justice reform, The Whole Pie offers the reassuring reminder that the bulk of incarceration flows from the policy choices made by state and local – not federal – governments.

- Era of Mass Incarceration: Why State Officials Should Fight Jail Growth

The U.S. jail population tripled over the last three decades, and our first-of-its-kind report looks at state trends to answer the question: what’s actually driving jail growth? With over 150 state-level graphs and state-by-state comparisons, we expose the real drivers of jail growth: pre-trial detention and the renting of jail space to other authorities. Our report makes the case that state officials need to pay far more attention to local jails.

- Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie

With 219,000 women locked up in facilities operated by thousands of agencies, getting the big picture can be difficult. In our most recent report, we uncover where and why women fall under the control of our local, state, and federal systems. For the first time, we use our “whole pie” approach to give the public and policymakers the foundation to end mass incarceration without leaving women behind.

Investigative reporters are illuminating little-known facets of the criminal justice system. We share our favorite work from 2017.

by Wanda Bertram and Wendy Sawyer,

December 28, 2017

Each year, investigative news reporters find new ways to shed light on the complicated problems of the criminal justice system. These are some of the in-depth stories and analyses that impressed us most in 2017:

- Ability to vote compromised for thousands behind bars

La Risa Lynch

The Chicago Reporter

July 10, 2017

A timely Chicago Reporter investigation this year raised the question: How many people are disenfranchised by the criminal justice system, not because of a felony record, but because they are in jail awaiting trial? Of the 700,000 people in jail in 2015, 63 percent were still eligible to vote, and poor Black and Latino defendants were overrepresented among them. The Chicago Reporter story reveals that local sheriffs and election officials hold the keys to empowering eligible voters in jail to vote, and how inconsistent their efforts are to facilitate registration and voting. Adding a new dimension to the problem of disenfranchisement by the criminal justice system, this piece calls attention to America’s jail problem at a time when it is urgently needed.

- Foster Care as Punishment: The New Reality of ‘Jane Crow’

Stephanie Clifford and Jessica Silver-Greenberg

The New York Times

July 21, 2017

The American foster care system is famously troubled, but a New York Times investigation this year revealed that New York City’s Administration for Children’s Services often punishes poor parents by taking their children away in “emergency removals” aided by the police. According to public defenders, poor Black and Hispanic mothers are most affected – held to unreasonably high standards in court, closely watched by caseworkers, and sometimes even arrested. The practice is so widespread that landlords have weaponized it, threatening to call Children’s Services on lower-paying tenants. This is an alarming example of the criminalization of poverty via implicit biases at government agencies.

- A 911 plea for help, a Taser shot, a death- and the mounting toll of stun guns

Peter Eisler, Jason Szep, Tim Reid and Grant Smith

Reuters

August 22, 2017

Reuters left no stone unturned in its six-part series on Taser stun guns this year. In this first piece alone, the investigative team examined over 1,000 deaths that followed police use of Tasers, finding that a quarter of those who died were suffering from a mental health crisis or neurological disorder at the time. In more than 100 cases, police had initially been called to respond to a medical emergency. At a time when police use of force is headline news, Reuters shows that even “safer” alternatives to firearms can be excessive, and even deadly. (See Part 6 for a similar analysis of the use of Tasers on incarcerated people.)

- When Junk Science About Sex Offenders Infects the Supreme Court

David Feige

New York Times

September 12, 2017

To date, the U.S. Supreme Court has approved draconian restrictions on people accused of sex offenses because the odds of committing another offense are “frightening and high” and “as high as 80%”. On what did the court base that finding? Legal scholars Ira and Tara Ellman followed the footnotes to find that it’s based on basically nothing at all.

David Feige mentions this story very briefly in his 2016 Untouchable documentary, and goes deeper in this September New York Times op-ed and 8-minute documentary to meet the people behind those early articles.

At the risk of ruining the documentary’s narrative arc, the “frightening and high” language comes from an article not in a science magazine, but in a popular magazine. At the time (in 1986) there wasn’t much research on sex offense recidivism, and the studies ranged from rates of 35% to 80%. So what does the author of that original article think about using his article to say that all people convicted of sex offenses recidivate at 80%? He says “That’s absolutely incorrect. It’s wrong. It’s not true.” And the idea that laws were based on his writing in a non-scientific magazine? He’s appalled. The documentary raises the question: now that modern research says that the recividism rate is in the range of 1% to 3%, why do the courts insist on citing the more dramatic, if completely wrong, figure?

- Amid Opioid Crisis, Insurers Restrict Pricey, Less Addictive Painkillers

Katie Thomas and Charles Ornstein

The New York Times

September 17, 2017

The New York Times and ProPublica collaborated on this investigation of the role insurers play in the ongoing opioid crisis. In their analysis of Medicare prescription plans and interviews with patients and professionals, they found that insurers often restrict access to safer, more expensive treatments, and leave patients with chronic pain few options but to take cheaper, more addictive drugs. Insurers often made it easier to get addictive substances than to get non-drug treatments and even treatment for addiction. While this article doesn’t touch upon the criminal justice implications, there are more than 1 million arrests for drug possession each year and two-thirds of people in jail have a history of a substance use disorder – even though it’s clear that the deck is stacked against people who need safe treatment, not punishment.

- They confessed to minor crimes. Then City Hall billed them $122k in ‘prosecution fees’

Brett Kelman

The Desert Sun

November 15, 2017

Silver and Wright, a private law firm contracted as city prosecutor for two southern California towns, has been using its power to take residents to court for minor crimes and then hand them sky-high bills for their own prosecution. A Desert Sun investigation found that the cities billed 18 defendants more than $120,000 in prosecution fees – defendants mostly charged with public nuisance crimes, like overgrown weeds – and threatened to take away their homes if they did not pay. Brett Kelman details one of the most egregious recent examples of the privatization of justice functions leading to the exploitation of defendants.

- How Trump’s Hands-Off Approach to Policing Is Frustrating Some Chiefs

Steve Eder, Ben Protess and Shaila Dewan

The New York Times

November 21, 2017

President Trump’s Justice Department, which has treated excessive force by police as a non-issue, announced in September that it would scale back a program that offered guidance to troubled police departments. The Justice Department calls its new approach “hands off,” but a New York Times deep dive found that many police chiefs are pushing back, saying the program was collaborative and useful. Resistance from police chiefs of all stripes points to a “growing consensus” that building bridges with underserved communities should be a public safety priority.

- More women are jailed in Texas, even though arrests have dropped. Why?

Cary Aspinwall

The Dallas Morning News

December 3, 2017

The Dallas Morning News combed through monthly data from sheriffs’ offices to discover an alarming trend: The number of unconvicted women in Texas jails has climbed by 48 percent since 2011. Cary Aspinwall profiles jailed women who are part of this upward trend, and explains that what’s driving women’s jail growth in Texas is that women “keep going back, trapped in a cycle of debt and poverty and drug addiction.” The piece represents growing awareness of the problem of women’s mass incarceration in local correctional facilities. (To learn about women’s incarceration in your state, stay tuned for our next report, The Gender Divide, due out in January 2018.)

A few of our favorite examples of writing that pushed the envelope and shined light on some of the most pressing issues for criminal justice reform today.

by Wendy Sawyer,

December 27, 2017

This year, we were pleased to see more writers, researchers, and advocates take a stand against mass incarceration. Here are some of our favorite examples of writing that pushed the envelope and shined light on some of the most pressing issues for criminal justice reform today:

- The price of justice doesn’t cover the bills

By Jon Wool

USA Today

April 21, 2017

New Orleans, called by its mayor the “most incarcerated city in the most incarcerated state in the most incarcerated country in the world,” is finally trying to reduce its jail population. In this column, the director of the Vera Institute of Justice New Orleans explains how jail incarceration on this scale is driven by the perverse incentives of state agencies – including courts – to squeeze money out of the city’s disproportionately Black and poor defendants through money bail and conviction fines and fees. New Orleans is not alone in this practice, but it perfectly illustrates the deep dysfunction and injustice caused by funding courts through the fines and fees they impose on society’s most disadvantaged.

- When a Computer Program Keeps You in Jail

By Rebecca Wexler

New York Times

June 13, 2017

In an op-ed that will keep you up at night, Rebecca Wexler explains what happens when automated technologies become a widely accepted but unaccountable part of the criminal justice process. “At every stage – from policing to investigations to bail, evidence, sentencing and parole – computer systems play a role”, but the privately owned, for-profit companies behind these systems are refusing to explain how their products work when they produce questionable outcomes, claiming “trade secret” privilege. When key criminal justice decisions are based on black box algorithms, and private interests are protected above due process, the legitimacy of the system is at stake.

- When Prisoners Are a “Revenue Opportunity”

By Brian Alexander

The Atlantic

August 10, 2017

Brian Alexander of The Atlantic breaks down all of the problems with the “video visitation” contracts that are quietly replacing in-person visits in local jails across the country. Connecting the dots between the low-quality video chats, the elimination of in-person visits, administrative hurdles to discourage free on-site calls, hidden fees, “bundled” video and phone services, and commissions paid to counties, this piece offers a complete picture of the exploitative nature of “video visitation” for the uninitiated. Going beyond the basics, however, Alexander points to the growing interest of private equity firms in prison and jail telecommunications as further evidence that the system of mass incarceration has created a lucrative market to be exploited.

- My Brother, the Violent Offender

By Josie Duffy Rice

Slate

August 14, 2017

Josie Duffy Rice’s story of her brother, who struggles with the stigma of a violent felony conviction, gives real-life context to her deeper discussion of one of the most pressing questions for criminal justice reformers today: How should our society define – and respond to – violence? Furthermore, how can we help people with violent convictions succeed, instead of trapping them in a cycle of incarceration and poverty? Given that more than half of the people in state prisons are incarcerated for violent offenses, Rice reminds us, we can’t radically decarcerate without rethinking violence.

- I Can’t Visit My Sons in Prison Because I Have Unpaid Traffic Tickets

by Joyce Davis as told to Eli Hager

The Marshall Project

September 14, 2017

Joyce Davis, a grandmother with cancer living on a fixed income, has no criminal record but does have $1,485 in tickets she can’t afford to pay. In this heartbreaking narrative for The Marshall Project’s “Life Inside” series, she questions why that was cause for the Michigan Department of Corrections to refuse her request to visit her sons in prison. Her story adds a disturbing coda to the long list of ways fines and fees trap poor defendants: to induce payment, the state will even keep your children from you if it can.

- We are Reclaiming Chicago One Corner at a Time

By Tamar Manasseh

New York Times

October 22, 2017

In this op-ed, Tamar Manasseh offers a straightforward solution to gang violence, and it’s not what the Trump administration has in mind: shift resources to neighborhoods for job training, better schools, safe spaces for kids, and community programs. She’s seen it work in one of Chicago’s most violent neighborhoods, where her community organization has supervised and fed kids for three years and watched as violent crime fell and student performance improved. Manasseh reminds us that public safety doesn’t require the knee-jerk responses of more police and harsher punishments, but rather giving communities the resources they need to take care of themselves.

States can still determine the future of mass incarceration. We share our ideas for winnable justice reform in 2018.

by Aleks Kajstura,

December 20, 2017

This report has been updated with a new version for 2022.

The 2018 legislative session is just around the corner, and we’ve compiled — as we do every year — a list of under-discussed but winnable criminal justice reforms. Despite the White House’s efforts to set the country back on criminal justice, the good news is that states remain empowered to determine the future of mass incarceration.

The 2018 legislative session is just around the corner, and we’ve compiled — as we do every year — a list of under-discussed but winnable criminal justice reforms. Despite the White House’s efforts to set the country back on criminal justice, the good news is that states remain empowered to determine the future of mass incarceration.

The list is published as a briefing with links to more information and model bills, and it was recently sent to reform-minded state legislators across the country. Our list of reforms ripe for legislative victory are:

- Ending prison gerrymandering

- Lowering the cost of calls home from prison or jail

- Protecting in-person family visits from the video visitation industry

- Stopping automatic driver’s license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving

- Repealing or reforming ineffective and harmful sentencing enhancement zones

- Protecting letters from home in local jails

- Requiring racial impact statements for criminal justice bills

- Repealing “Truth in Sentencing”

- Creating a “safety valve” for mandatory minimum sentences

- Immediately eliminating “pay only” probation and regulating privatized probation services

- Reducing pretrial detention

- Decreasing state incarceration rates by reducing jail populations

- Prohibiting prisons and jails from using “release cards” with built-in fees

Could your state be working on any of these reforms? We’re looking forward to the progress we can make together in 2018!

The New York Times looks at how corruption is tolerated and even encouraged in some county sheriff offices.

by Stephen Raher,

December 20, 2017

A lengthy and thoroughly researched article in last week’s New York Times provides a detailed look at how corruption is tolerated and even encouraged in some county sheriff offices. The story focuses on Sheriff Ana Franklin, of Morgan County, Alabama; but, it also points to some larger issues that can easily be found in communities throughout the country. In particular, there are three issues in the article that deserve repeating: food, rodeos, and populism.

Food

(And the hidden ways sheriffs make money)

Sheriff Franklin’s time in office has been marked by controversy for several reasons, but one transgression is a real attention grabber. The sheriff invested $150,000 in public funds in a car dealership owned by someone who had been convicted of financial fraud (the dealership subsequently filed for bankruptcy). This questionable use of public money was facilitated by a bizarre quirk of state law:

In most [Alabama] counties — Morgan included — food money is deposited not into government accounts, but into sheriffs’ personal accounts. Nearly a decade ago, when inmates’ lawyers demanded to know how much of this money Alabama sheriffs were keeping for personal use, the state sheriffs’ association instructed them not to answer.

This practice has led to an unfortunate temptation: some sheriffs try to spend as little as possible on jail food (a cruel practice that also raises public health concerns), so that they can keep any unspent funds for themselves. While this scheme may be legal in other counties, Sheriff Franklin ran into trouble because she was subject to an unusual level of oversight: the Southern Center for Human Rights had sued Franklin’s predecessor for inadequate food at the jail, and the litigation ended in a consent decree that requires the food budget to be spent entirely on food.

The Times article also explores out how this specific incident fits into a bigger trend that impacts jails all over the country, even in jurisdictions without Alabama’s lax budgetary practices. The more jails seek to generate revenue from incarcerated people, the more opportunities for unfairness will arise:

Sheriffs have found other ways to squeeze money out of inmates. Some take a percentage of service contracts, including commissary sales and telephone charges. In Morgan County, a company that just won the jail phone contract pays the county a 90 percent commission on all its revenue from prisoners’ calls. In St. Johns County, Fla., the sheriff brings in tens of thousands of dollars a year by charging inmates “processing fees.”

Prison Policy Initiative has been tracking monetization schemes like phone systems and commissary for a while. But this article makes an important point: as more incarcerated people are held in county jails, the potential profits for unscrupulous parties increases.

Rodeos

(and sheriffs’ questionable “charitable” fundraising)

The Times article also reveals some surprising details about law-enforcement related fundraising. Sheriff Franklin has expanded the size (and revenue) of Morgan County’s sheriff’s rodeo, amid allegations that deputies sold program advertisements while on duty, and were asked to work at the event without pay. Even more dismaying, it’s not clear whether the stated goal of the rodeo is even being met:

Sheriff Franklin said the rodeo brought in about $20,000 a year in profit, but she has never publicly accounted for all the money, except to say that it went to local charities and law enforcement. She promised to produce financial records for her rodeo, but a month later gave only names of charities and no amounts. The rodeo’s financial records, she said, were “reviewed by a C.P.A. firm.”

In interviews, the sheriff gave differing accounts about who processed the rodeo cash. First she said the money went through a tax-exempt organization set up a couple of years ago called Morgan County Sheriff’s Rodeo. Before that, the money was kept in a regular account, she said.

After The Times could find no group by that name registered with the Internal Revenue Service, Sheriff Franklin corrected herself, saying rodeo proceeds had actually gone to a different nonprofit: Morgan County Sheriff’s Mounted Posse, founded in 1963.

Normally, tax-exempt organizations must file annual financial reports for public inspection. But Sheriff Franklin’s is exempt from public disclosure because of an I.R.S. loophole for charities affiliated with government agencies. “The I.R.S. assumes organizations controlled by governmental entities will be good tax citizens,” said Marc Owens, former director of the I.R.S. division of exempt organizations.

Populism

(And law enforcement’s anti-government rhetoric )

Not only are the accounting irregularities concerning, but the very nature of the fundraising activities highlights sheriffs’ highly political role and the ability to monetize the image that comes with the office. The article notes that some sheriffs have adopted a particularly anti-government platform which has gained popularity in recent years:

“In certain jurisdictions there is a feeling by sheriffs that this is my fiefdom — I am in charge, my way or the highway,” said Sarah Geraghty, a lawyer at the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta, which has filed lawsuits against a number of sheriffs. “Sometimes that kind of culture can lead to sort of a sheriffs-gone-wild kind of behavior.”

[…]

“Mostly we protect people from criminals, but sometimes we protect them from an overreaching government,” said Brad Rogers, the sheriff of Elkhart County, Ind. He added: “I’m answerable to the people. I have a face and a name. Try asking the federal government for a face and a name.”

This rhetoric can be found across the country, from Sheriff Rogers in Indiana, to former sheriff Joe Arpaio in Arizona, to Sheriff Glenn Palmer in Oregon (who publicly supported the protestors that seized the Malheur Wildlife Refuge in 2016). These populist law enforcers share a common tactic: they build and justify their own unaccountable power by attacking the legitimacy of other politicians or government entities. Because of the vast powers given to county sheriffs, it is critical that reformers closely monitor their local sheriffs and challenge policies that are grounded in emotional appeals to voter fear.

Conclusion

The Times has done a good job of illustrating some common problems that arise from sheriffs’ unchecked power. The question facing the rest of us is what can be done to reverse this trend. Sheriffs can be challenged at the next election, but unseating an incumbent sheriff is quite unusual. As the article briefly notes, litigation and the rare criminal prosecution can be useful tools. And other elected officials may not have the ability to hire or fire a sheriff, but can often use the power of the purse to force operational changes. As usual, there is no uniform simple solution to this intractable problem, but any meaningful change must begin with an informed an active general public.

Virtual jail "visits" are quietly sweeping the country. Fortunately, a surge of hard-hitting journalism is pushing back, illuminating the exploitative practice of eliminating family visits in favor of video calls.

by Lucius Couloute,

December 14, 2017

Virtual jail “visits” are quietly sweeping the country. Fortunately, a surge of hard-hitting journalism is pushing back, illuminating the exploitative practice of eliminating family visits in favor of video calls. In two new pieces from The Guardian and Colorado Public Radio, the technological glitches, emotional toll, and human rights violations stemming from an expanding jail video calling industry take center stage.

In Shannon Sims’ deep dive into the video calling industry for The Guardian, she investigates the switch from in-person family visits to expensive video calls in one jail outside of downtown New Orleans:

The guards tell me they think the new system will be an improvement – “it’s better because you can do a video visit from home now” – but since it is so new, they can’t say for sure.

They suggest I check out the new “Video Visitation Center”, located about a 10 minute drive down the freeway. For those without access to a smartphone or a computer, the new visitation center is their only option.

There, an old elementary school building has been converted into the center. Inside, three guards are gathered and laughing around a cellphone behind a glass wall, but outside the parking lot is empty. No one is visiting.

As we’ve detailed before, it’s unlikely that people will actually enjoy driving to a jail or offsite terminal just to visit with a computer screen – the entire experience is dehumanizing. But video calling from home – at $12.99 per call – wasn’t much better for Tiffany Burns, who Sims visited as she was attempting to receive a home video call from her boyfriend Chrishon Brown:

“OK, so he is supposed to call in eight minutes I guess,” she says, staring at her phone, which blinks 6.52pm.

This is her third attempt to video chat with Brown. The first time, she did not know she needed to schedule the call far ahead of time, and the second time, all the slots were filled for the days she was off work. Now, with her slot scheduled and her earphones in, she’s wondering if it will all work out.

Finally, she sees a call coming through.

Her face lights up and then slowly fades as she realizes Brown can’t hear her. She fiddles with her headphones, waves, tries gesturing to him, but ultimately, he never can hear her voice. The two end up simply giggling at the screen image of each other for the remainder of the time.

Later, I speak with Brown by phone and he explains that he believes he was only the third inmate to try to use the video program at the Jefferson Parish jail, and that the other two also said it didn’t work properly.

“We had to pay money for something that didn’t work,” he complains. “I couldn’t even hear what she was saying, and I couldn’t really see her.”

A thousand miles away in Denver, Colorado, Michael Sakas of Colorado Public Radio explores the emotional toll that eliminating in-person visits has taken on one mother’s incarcerated son, who has attempted suicide multiple times while behind bars:

“He is having an emotional breakdown right now because he can’t wait to give me a hug . . . So he wants to plead guilty because he wants to go to prison so that he can give me a hug again.”

Since 2005, the only way to speak to an incarcerated person in Denver’s jails has been through video chats. But a new movement, sparked by grassroots leaders and a report from Denver’s Office of the Independent Monitor, is putting pressure on the local sheriff’s office, which is now considering a reinstatement of in-person visits. The downtown detention center was built without visitation space, which would make reinstating visits expensive, according to jail division chief Elias Diggins. But the city is moving forward with a $1.4 million dollar contract to update the video calling system.

“Can you imagine being in a cell all by yourself, and only being out for a couple of hours everyday? I mean, I couldn’t handle it. Could you?”

The Guardian‘s article raises another important point that we haven’t raised in our own work or seen raised elsewhere: does international human rights law require jails to allow in-person visitation?

“Internationally, multiple legal instruments indicate that it [does]. UN rules call for the allowance of visitors, while the European Prison Rules emphasize that while all forms of visitation may be monitored, maximum contact is the underlying goal: ‘Prisoners shall be allowed to communicate as often as possible by letter, telephone or other forms of communication with their families, other persons and representatives of outside organisations and to receive visits from these persons.'”

This reminder about international human rights law adds an international layer to the clear national consensus — including agreement from editorial boards, public citizens, professional organizations, and policymakers — that erecting unnecessary barriers between incarcerated people and the outside world is bad policy. It’s time for American sheriffs to join the rest of the country, and the world.

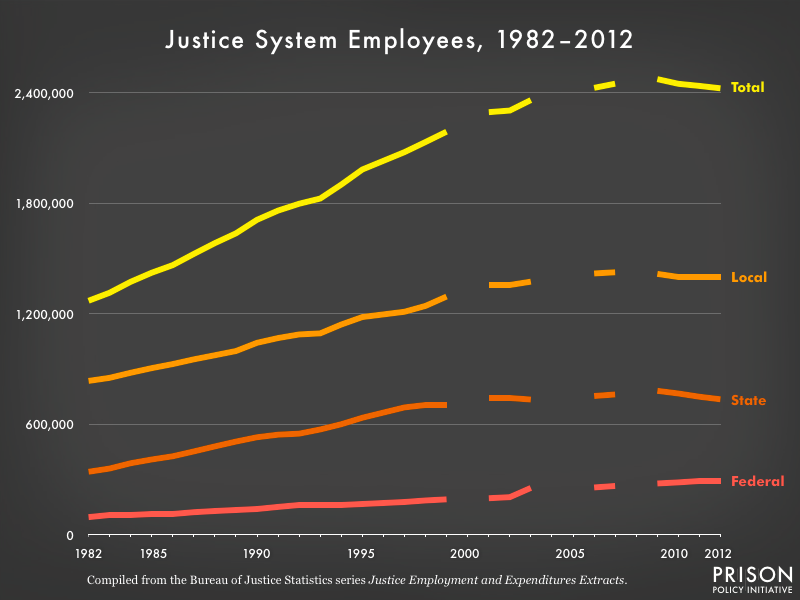

This country employs more people to run the justice system than to grow food.

by Emily Widra,

December 7, 2017

One of the most popular parts of our 2003 book The Prison Index: Taking the Pulse of the Crime Control Industry concerns the economic power of the criminal justice system. I updated three of the graphs and concepts from that book:

Bureau of Justice Statistics data on the number of justice system employees was not available for the 2000, 2004-2005, and 2008. If you know of a source for this data, please be in touch.

Bureau of Justice Statistics data on the number of justice system employees was not available for the 2000, 2004-2005, and 2008. If you know of a source for this data, please be in touch.

The justice system may have slowed its growth in recent years, but it still has a large hold on the economy. In 2012 — the most recent data available — the more than 2.4 million people who work for the justice system (in police, corrections and judicial services) at all levels of government constituted 1.6% of the civilian workforce.

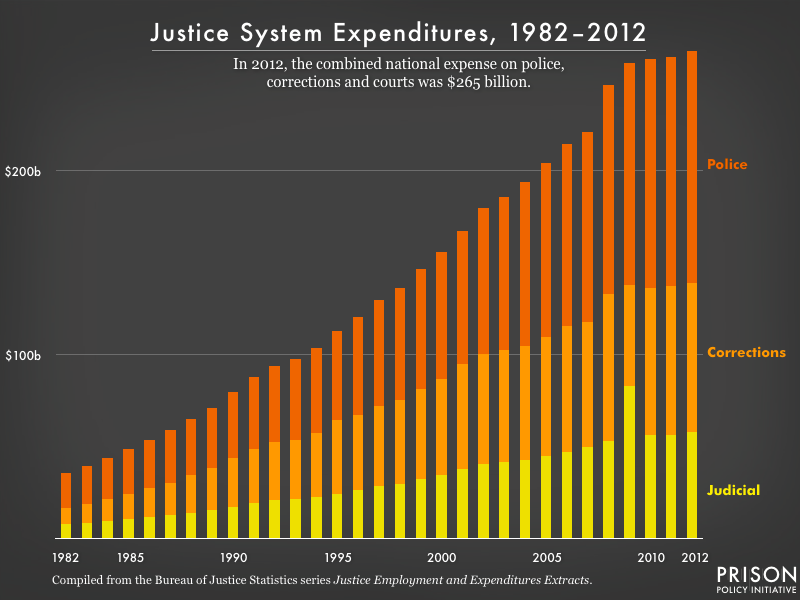

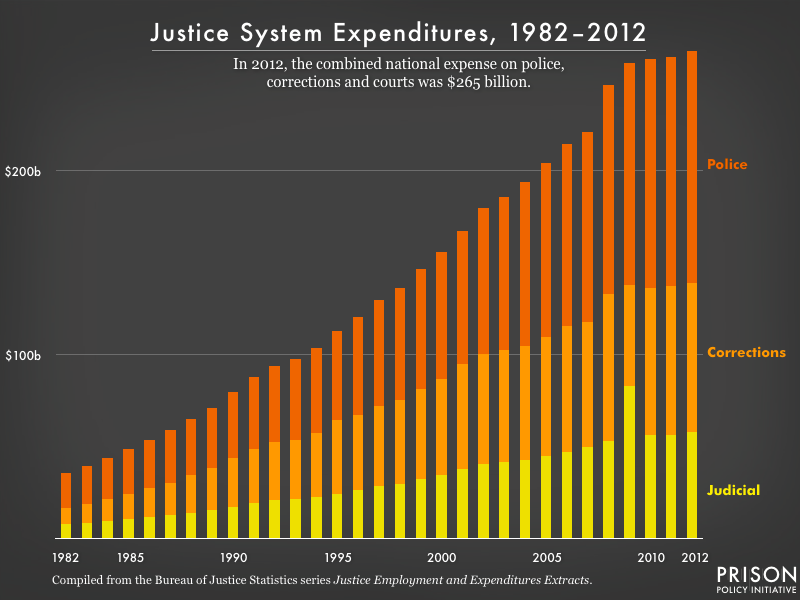

The expenditures are tremendous, having risen from $36 billion in 1982 to $265 billion in 2012:

These helpful historical figures are different from the our January report Following the Money of Mass Incarceration, which found that mass incarceration costs $182 billion a year. The Bureau of Justice Statistics data counts all justice system expenditures including expenses for the enforcement of civil law, but does not include the various costs to families and defendants. Our report includes those family costs (and offers a detailed breakdown of the expenses) and makes some estimates to exclude those civil costs to focus on criminal law enforcement. While the Following the Money report is useful to answer a lot of specific questions, that analysis is not available over time.

These helpful historical figures are different from the our January report Following the Money of Mass Incarceration, which found that mass incarceration costs $182 billion a year. The Bureau of Justice Statistics data counts all justice system expenditures including expenses for the enforcement of civil law, but does not include the various costs to families and defendants. Our report includes those family costs (and offers a detailed breakdown of the expenses) and makes some estimates to exclude those civil costs to focus on criminal law enforcement. While the Following the Money report is useful to answer a lot of specific questions, that analysis is not available over time.

The sheer scale of our nation’s investment in mass incarceration and over-criminalization reflects a larger transformation of our society and our priorities. For example, now more people work for the justice system than work to grow food:

The 2.3 million incarcerated people in the United States are, of course, excluded from the labor force and therefore are not reflected in analyses of labor force participation. Including them would make the portion of the workforce that is involved in the mass incarceration system even larger.

The 2.3 million incarcerated people in the United States are, of course, excluded from the labor force and therefore are not reflected in analyses of labor force participation. Including them would make the portion of the workforce that is involved in the mass incarceration system even larger.

Looking at the historical data shows this huge system didn’t grow overnight, but that the gradual policy changes that led to mass incarceration have created a powerful lobby to defend the status quo. We have our work cut out for us.

Sources:

The Current Population Survey, conducted by the Bureau of Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics, reports the number of agricultural workers and the size of the total labor force for each year from 1946 to present.

The Justice Employment and Expenditures Extracts series published by the Bureau of Justice Statistics reports the number of police, corrections and judicial employees for most years from 1982 to 2012. The data for the years 1988, 1989, 1991, 1993, 1994, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2001, 2003-2006, and 2008 were missing, so we imputed by assuming a linear trend between the most recent available years. (We converted these figures to percentages by dividing them by the total labor force figures reported by the Current Population Survey.) Data for 1980 and 1981 did not include judicial employees, so we estimated judicial employment from the 1979 and 1982 values.

Please click to see the full visualization.

Please click to see the full visualization.

The 2.3 million incarcerated people in the United States are, of course, excluded from the labor force and therefore are not reflected in analyses of labor force participation. Including them would make the portion of the workforce that is involved in the mass incarceration system even larger.

The 2.3 million incarcerated people in the United States are, of course, excluded from the labor force and therefore are not reflected in analyses of labor force participation. Including them would make the portion of the workforce that is involved in the mass incarceration system even larger. Please click to see the full visualization in its original context.

Please click to see the full visualization in its original context.  Figure 1. Most state policymakers are not tracking jails in the first place, and the jails’ frequent practice of renting cells to other agencies makes it difficult to draw conclusions from the little data that is available. This report offers a new analysis of federal data to offer a state-by-state view of how jails are being used and we find that, even more than previous research has implied, pre-trial populations are driving “traditional jail” growth. The data behind this graph is in Table 1.

Figure 1. Most state policymakers are not tracking jails in the first place, and the jails’ frequent practice of renting cells to other agencies makes it difficult to draw conclusions from the little data that is available. This report offers a new analysis of federal data to offer a state-by-state view of how jails are being used and we find that, even more than previous research has implied, pre-trial populations are driving “traditional jail” growth. The data behind this graph is in Table 1. In at least 38 states, a senator, governor, and/or attorney general holding office in the past 10 years was once a prosecutor. This chart may understate the prevalence of these “prosecutor politicians,” since the source is a work in progress and has no data for some positions in five states as of July 7, 2017, and does not include changes in all offices after January 2017.

In at least 38 states, a senator, governor, and/or attorney general holding office in the past 10 years was once a prosecutor. This chart may understate the prevalence of these “prosecutor politicians,” since the source is a work in progress and has no data for some positions in five states as of July 7, 2017, and does not include changes in all offices after January 2017.

The end of American prison visits: jails end face-to-face contact – and families suffer

The end of American prison visits: jails end face-to-face contact – and families suffer NBA Pistons Owner Under Fire for Deal on Inmate Phone Service

NBA Pistons Owner Under Fire for Deal on Inmate Phone Service What’s actually driving local jail growth?

What’s actually driving local jail growth? The plunder of the American prison system

The plunder of the American prison system Driver’s Licenses, Caught in the War on Drugs

Driver’s Licenses, Caught in the War on Drugs

Bureau of Justice Statistics data on the number of justice system employees was not available for the 2000, 2004-2005, and 2008. If you know of a source for this data, please be in touch.

Bureau of Justice Statistics data on the number of justice system employees was not available for the 2000, 2004-2005, and 2008. If you know of a source for this data, please be in touch. These helpful historical figures are different from the our January report

These helpful historical figures are different from the our January report